Use of stimulants in the treatment of children in the United States increased steadily between 1989 and 1996 (

1,

2), but little is known about how this trend is related to combination pharmacotherapy in which stimulants are used with other psychotropic agents.

Stimulants may be prescribed alone or with other medications for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). There are indications that combined psychopharmacotherapy with stimulants is on the rise (

3). It has been estimated from data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an annual survey of a representative sample of U.S. office-based physician practices (

4), that a stimulant is prescribed during 83 percent of physician office visits for the treatment of ADHD; in 10 percent of these visits, additional psychotropic medications are prescribed (

2). Because these data were pooled across eight years, however, trends in such combined pharmacotherapy cannot be determined.

To explore whether combined pharmacotherapy with stimulants is increasing, we examined NAMCS prescription data for the periods 1993-1994, 1995-1996, and 1997-1998. We combined the data from pairs of consecutive surveys to obtain larger samples. Sample sizes for all visits in which a stimulant was prescribed were 231 (weighted, 4,810,000) for 1993-1994, 228 (weighted, 4,530,000) for 1995-1996, and 203 (weighted, 4,980,000) for 1997-1998.

As described elsewhere (

1), we examined 11 categories of psychotropic medications prescribed for patients under age 18. We determined the frequency of outpatient visits that included a prescription for a stimulant and determined the proportion of these visits that involved concurrent prescription of any other psychotropic agent.

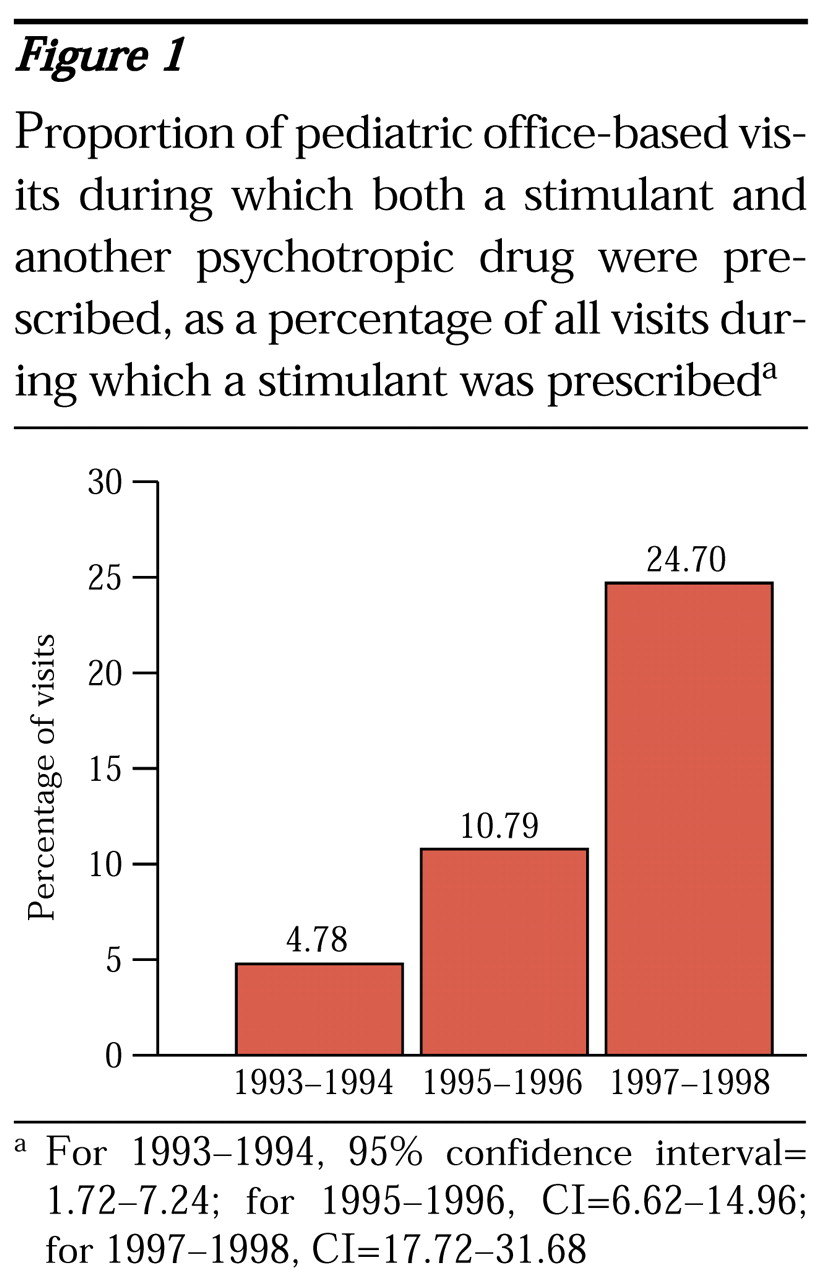

Among pediatric office visits between 1993 and 1998, 1.46 percent to 1.66 percent, or nearly two million visits a year, involved prescription of a stimulant. As

Figure 1 shows, of these visits, the proportion that included a concomitant prescription for any other psychotropic agent increased fivefold during the study period, from 4.78 for 1993-1994, to 10.79 for 1995-1996, to 24.70 for 1997-1998. The most commonly prescribed concomitant psychotropic medications were clonidine and various antidepressants.

Our results should be interpreted cautiously, because the sample was small and because NAMCS data do not provide estimates of patients' actual drug use, and thus use may have been overestimated because of noncompliance. Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that definitive safety and efficacy data are needed to support common forms of combined psychopharmacotherapy among youths.