The onset of schizophrenia typically occurs during adolescence or early adulthood (

1). Retrospective studies indicate that before onset most patients experience a prodromal phase of illness (

2). Clinical manifestations of the prodromal phase have been characterized by a slow development of heterogeneous symptoms, including social withdrawal, decreased interest, poor hygiene, increased irritability, and attenuated positive symptoms—unusual thought content and perceptual abnormalities (

3,

4).

The results of recent studies suggest that this prodromal state may be identified prospectively on the basis of current symptoms and decreased functioning (

5). A semistructured interview—the Structured Interview for Prodromal States (SIPS) (

6)—has been developed, and preliminary data suggest that it has excellent interrater reliability. Other data suggest that about 54 percent of persons who experience this symptomatic state develop psychosis within one year. Data underscoring the symptomatic nature, functional disability (

6), and cognitive impairment (

7) associated with the prodromal state support a need for research into treatment interventions for this population.

We examined data collected for persons with a prodromal diagnosis who either enrolled in an early intervention medication trial or agreed to a no-treatment follow-along. Our aim was to determine whether our patients had previously sought community psychiatric services.

Methods

Forty-seven consecutive patients who met the criteria for a schizophrenic prodromal state on the basis of the SIPS between February 1998 and April 2001 were included in the study. These patients had been referred by community providers—general practitioners, psychiatrists, and other mental health providers (25 patients, or 53 percent); by family members (ten patients, or 21 percent); and by others (12 patients, or 26 percent). Patients who screened positive for the prodrome were told that they were at risk of developing schizophrenia, meaning that they may or may not develop it. Patients were informed of the availability of a placebo-controlled clinical trial of an atypical antipsychotic medication for delaying or preventing the onset of psychosis. The study was approved by the human investigation committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Medical records, notes from the screening interview, records from the referral or telephone screening, and SIPS scores were reviewed by the first author to identify any previous psychiatric diagnoses, prescriptions for psychotropic medications, and psychiatric hospitalizations. A best-estimate approach (

8) was used to synthesize the final assessment.

Results

Thirty-two of the patients (68 percent) were male, and 15 (32 percent) were female. The patients ranged in age from 12 to 35 years; the mean± SD age was 17±5 years. Twenty-seven patients (57 percent) were white, six (13 percent) were African American, 12 (26 percent) were Hispanic, one (2 percent) was Asian American, and one (2 percent) was of an unspecified ethnicity.

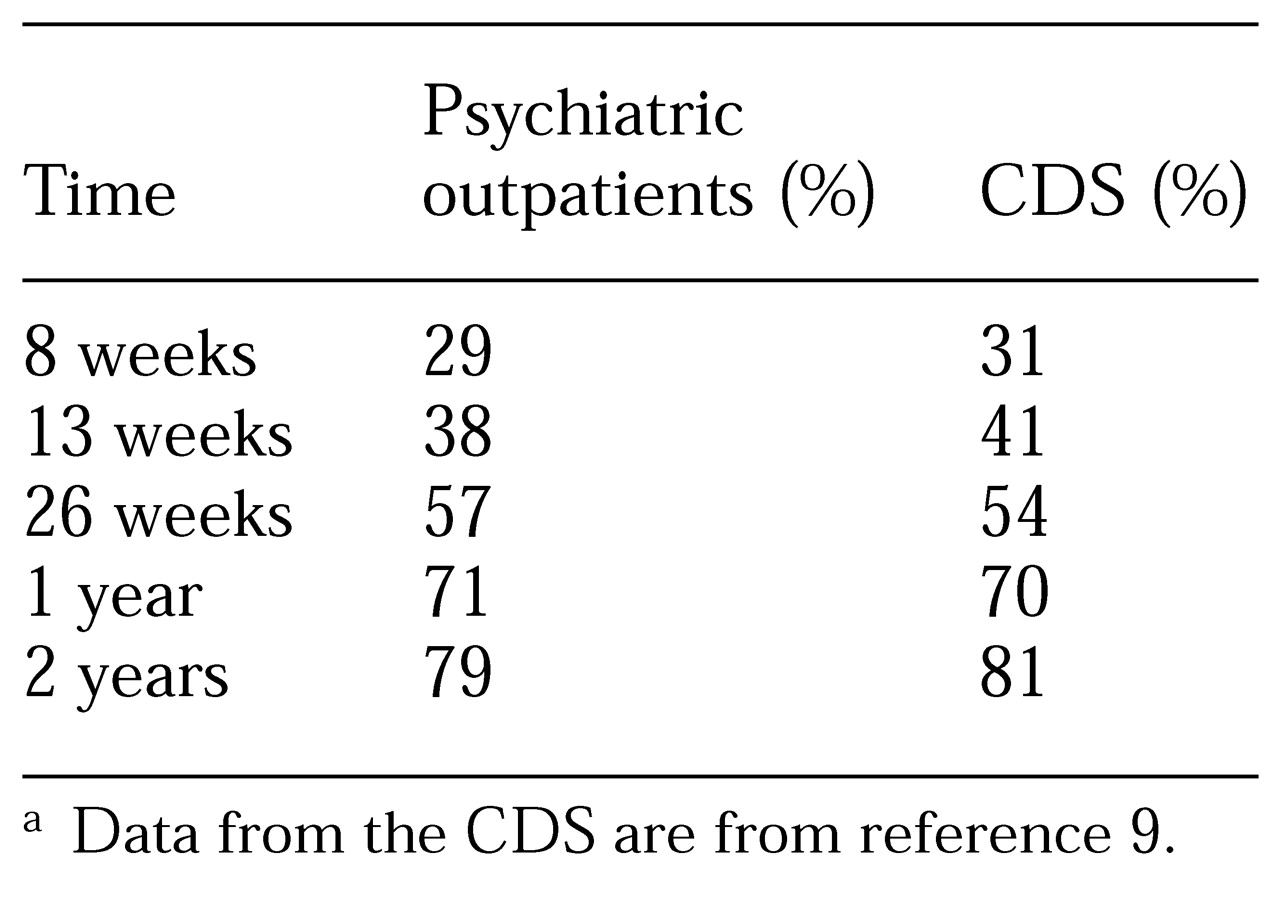

Of the 47 patients, 42 (90 percent) had a history of contact with a physician who had prescribed psychotropic medications or with a mental health practitioner. Thirty patients (64 percent) had received a prescription for a psychotropic medication, and four (9 percent) had had at least one previous psychiatric hospitalization. As shown in

Table 1, 22 patients (47 percent) had received a prescription for an antidepressant, nine (19 percent) for a stimulant, and six (13 percent) for an antipsychotic medication.

Twenty-eight (60 percent) of the patients had received diagnoses of psychiatric conditions in the past, and most of them had received more than one diagnosis. Most frequent were diagnoses in the affective disorders spectrum (11 patients, or 23 percent), followed by attention-deficit disorders (eight patients, or 17 percent). The former category included depressive disorder not otherwise specified (seven patients), major depressive disorder (two patients), bipolar disorder (one patient), and dysthymic disorder (one patient). Twelve patients (26 percent) received other axis I diagnoses, including Asperger's syndrome or pervasive developmental disorder (two patients, or 4 percent), tic disorder (one patient, or 2 percent), oppositional disorder or conduct disorder (three patients, or 6 percent), and adjustment disorder (two patients, or 4 percent). Two patients (4 percent) had a previous diagnosis of schizotypal personality traits.

Discussion

Our principal finding was that the majority of patients who met the criteria for a schizophrenic prodromal state had previously received psychiatric treatment, including psychotropic medication, and had received psychiatric diagnoses. The data from our study strongly suggest that these patients constitute a clinical population and that research into treatment interventions for this group of patients is indicated.

The main limitations of this study are related to sample selection bias and the method used to review medical records. Given that the patients—through family members or providers—had initiated contact for evaluation, our sample may have led to overrepresentation of the degree of treatment-seeking behavior among patients with prodromal symptoms. Alternatively, our study design could have resulted in underrepresentation of treatment seeking among such patients if a large number had been treated successfully by community providers. The method of chart review that we used has all the limitations of retrospective data collection.

The question of co-occurring disorders in this population remains to be clarified. Previous diagnoses could have involved comorbid disorders that were stable or in remission when the patient was enrolled in our study. It is also conceivable that the prodromal state is unstable and that patients presented with symptoms mimicking a variety of conditions at different times. Ultimately, answers to these questions require epidemiologic longitudinal sampling.

None of our patients had received a previous diagnosis of prodromal syndrome. There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, the patients may not have been experiencing prodromal symptoms at the time of their previous evaluations but may in fact have been experiencing symptoms of the disorder for which they received a diagnosis. Second, the schizophrenic prodromal state as a prospective diagnosis does not exist in clinical psychiatry. Third, practitioners may have considered it inadvisable to tell a patient, by way of diagnosis, that he or she was developing schizophrenia, knowing that this was only a possibility.

Fourth, providers may have been familiar with the prodromal state but may have preferred to record diagnoses that corresponded to billing codes or that could readily be associated with existing treatments. Fifth, diagnoses are preferred when they are perceived as more common, less severe, associated with a better prognosis, or leading to the prescription of medications that are generally perceived as safer. Sixth, the overlap of symptoms between the prodromal state and other disorders could lead to underdiagnosis of the prodromal state. This may be particularly true of depressive symptoms, which are common to both major depressive disorder and the prodromal state.

The majority of the patients in our sample had received a prescription for either an antidepressant or a stimulant. The degree of benefit associated with these medications was difficult to assess from our data. The patients who came to us were still compromised and seemed to have obtained little benefit. However, it is possible that other patients with prodromal symptoms were treated successfully with these medications and therefore never sought our evaluation. Moreover, it is not clear whether prescribing antidepressants and stimulants for patients in at-risk populations may induce psychotic symptoms or increase the severity of symptoms.

In this study, potential subjects were not excluded for having a previous antipsychotic prescription to treat prodromal symptoms. Thus we might have expected to see a higher rate of prescription of antipsychotic medications in our sample. Six of our patients had previously received a prescription for an antipsychotic medication, but not for their current prodromal symptoms. The absence of patients who had received a prescription to treat their current prodromal symptoms does not necessarily reflect a low rate of prescription of antipsychotic medications for prodromal symptoms in the community: patients with prodromal symptoms who were successfully treated with an antipsychotic medication would probably not have been referred to us.

Our findings suggest that broadening the differential diagnosis to include the prodromal state may be considered for patients who present with fluctuating symptoms that lead to a variety of psychiatric diagnoses over time, especially symptoms that prove to be treatment resistant.

Conclusions

Of 47 patients with a syndrome putatively prodromal to schizophrenia who were enrolled in our study, 90 percent had received some form of psychiatric treatment before enrollment. These data suggest that many patients who experience such a syndrome seek treatment and often receive psychosocial interventions and psychotropic medications from community providers. Clinical trials are needed to identify the risks and benefits of these interventions and to lay the groundwork for future treatment recommendations and guidelines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant MH-54446 from the U.S. Public Health Service to Dr. Woods, grant MH-01654 from the U.S. Public Health Service to Dr. McGlashan, and an investigator-initiated grant from Eli Lilly and Company to Dr. McGlashan.