The period between discharge from an inpatient setting and engagement in community services is a critical and vulnerable time for the continuity of care of persons with mental illness. Failure to engage in outpatient care after discharge has been shown to increase the likelihood of readmission (

1) and can compromise successful community adjustment (

2). Characteristics that influence the use of services after discharge can be categorized according to Andersen and Newman's model of health behavior (

3) as predisposing factors, enabling factors, need factors, and environmental factors. Individual characteristics that are often associated with attendance at follow-up appointments are younger age (

4,

5), low socioeconomic status (

4,

5,

6), and need for services as measured by diagnoses, severity of illness, length of hospital stay, or number of previous hospitalizations (

1,

6,

7,

8,

9).

Studies that have addressed geographic accessibility as an enabling factor have found either no association (

5) or a positive association (

9). System-related factors, such as whether the person has had previous contact with psychiatric services, whether someone else scheduled a follow-up appointment for the patient, whether the patient received reminders about the appointment, and time between discharge and follow-up, have been consistently associated with attendance at outpatient appointments (

4,

5,

8,

10).

In this study we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients who were discharged from a psychiatric hospital to identify factors related to attendance at their first scheduled outpatient appointment. We hypothesized that patients who lived farther from the clinic, lived in a rural county, were uninsured, were less severely ill, and had a longer wait between discharge and their follow-up appointment would be more likely to miss their appointments.

Methods

Discharge summaries for 877 (98 percent) of 894 patients who were discharged from the adult units of a university-affiliated psychiatric hospital in the Midwest during the six-month period beginning July 1, 1998, were reviewed. Data on scheduled follow-up appointments, appointments that were kept, and readmissions were obtained from the discharge summaries and from the hospital's administrative information system. Only patients whose scheduled follow-up appointments were at the university outpatient clinic were included in the study. For patients who were discharged more than once during the study period, only data on the first discharge were analyzed.

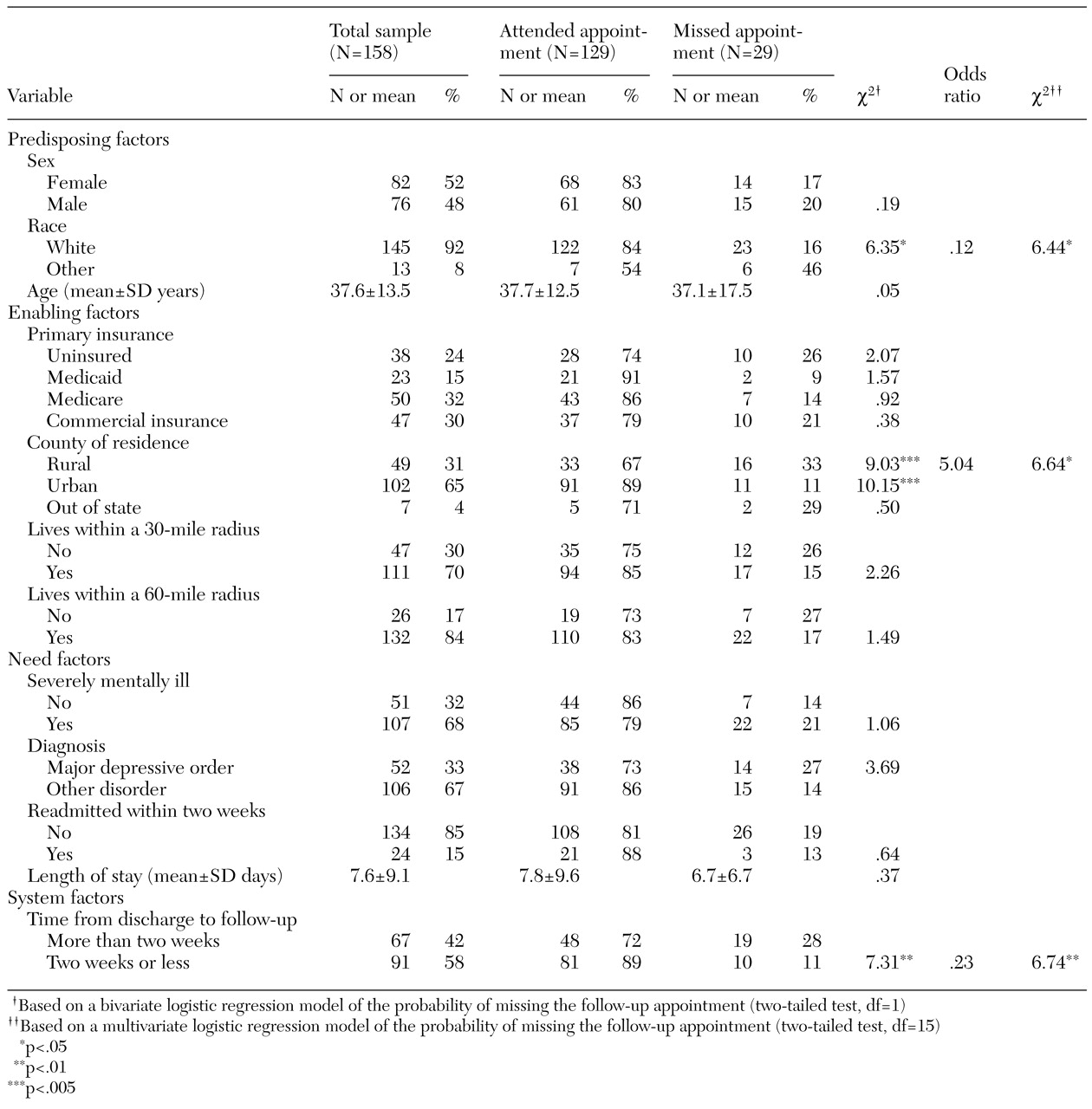

The dependent variable was attendance at the first scheduled appointment after discharge. Predisposing variables were age, race, and sex. Enabling variables were primary source of insurance at the time of admission (Medicare, Medicaid, commercial insurance, or none), geographic distance from the clinic, and whether the patient lived in an urban county (a metropolitan area with a population of at least 50,000), in a rural county, or out of state. Geographic distance was categorized as whether the patient lived within a 30-mile radius of the clinic and also whether the patient lived within a 60-mile radius of the clinic.

Need variables were an ICD-9 diagnosis of severe mental illness (major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified), whether the diagnosis was major depressive disorder or another mental illness, mean length of stay, and whether the patient was readmitted within two weeks of discharge. The only system-related variable that was available from the medical records was the date of the scheduled follow-up appointment. This variable was dichotomized by whether the scheduled appointment was within two weeks of discharge or more than two weeks after discharge.

Logistic regression analysis was used to model the likelihood that patients would miss their scheduled follow-up appointment. The predictor variables were included in bivariate logistic models to enable us to assess the usefulness of each variable in predicting attendance. The independent variables were then included in a multivariate logistic regression as a means of assessing the strength of the association between the risk variable and attendance at the follow-up appointment, independent of the effects of the other variables in the model.

Results

Of the 877 completed discharge summaries, 158 (for 158 patients) met the study criteria. Characteristics of these patients are summarized in

Table 1. Twenty-nine patients (18 percent) did not attend their scheduled follow-up appointment. The table also lists odds ratios for the variables that were significant in the multivariate model. Patients who were white were about eight times as likely to attend their scheduled follow-up appointment as patients who were not white. Patients who lived in an urban county or out of state were five times as likely to keep their follow-up appointment as patients who lived in a rural county. Patients whose scheduled follow-up appointments were within two weeks of discharge were about four times as likely to keep their appointment as patients whose scheduled follow-up appointments were more than two weeks after discharge.

Discussion and conclusions

The relationship we found between the time from discharge to the first follow-up appointment and nonattendance at that appointment is consistent with the results of previous studies (

4,

5,

10). However, the association we found between race and attendance was unexpected. It is possible that socioeconomic status, which was not controlled for in this study, accounted for the ethnic disparities we observed (

4). An alternative explanation is that racial homogeneity reduces cultural sensitivity; thus minorities in this predominantly Caucasian population may have been less satisfied with their care and less likely to attend their follow-up appointments. Regardless of the reason, this finding provides useful information for identifying persons who have an elevated risk of missing their first appointment after discharge from the hospital.

In a study of Nordic countries (

9), residents of rural areas were less likely than residents of other areas to attend their first follow-up appointment after discharge. However, in our study geographic distance to the clinic was not significantly associated with attendance. It is possible that patients who lived farther away but who nevertheless chose to attend their follow-up appointment had motivations that compensated for the distance, such as a preference for university services or a lack of local services. Another possible explanation is that patients who were unable or unwilling to obtain services locally had characteristics that made them less likely to keep any appointment. For example, rural residents who have conditions that are difficult to treat, such as co-occurring conditions, may be more likely to be referred to a university clinic.

Limitations of this study include uncertainty about the generalizabilty of the findings and selection bias. Only patients whose scheduled follow-up appointments were at the same site where they were hospitalized were included. Attendance rates may have been higher because the outpatient provider was familiar (

4,

8). Patients who had appointments to return to the university clinic may have refused—or been denied—local services for financial reasons or for reasons related to the nature and severity of their illness. In summary, patients who were referred to the university for follow-up may have been different from those who were referred elsewhere for various reasons that could have influenced the likelihood of their attending a follow-up appointment.

The results of this study confirm that characteristics of patients and of the delivery system influence attendance at a first follow-up appointment after hospital discharge. The findings suggest that scheduling these appointments within two weeks of discharge may increase the likelihood of attendance. Future studies should address whether an interim intervention during the first two weeks after discharge, such as a telephone call by a nurse or a case manager, would be equally effective.

This study has suggested a mechanism by which patients with an elevated risk of missing a follow-up appointment after discharge can be prospectively identified and the data used, within that setting, to develop strategies for enhancing the likelihood that at-risk patients will receive follow-up care.