Studies of quality of life among patients with social anxiety disorder have been conducted with epidemiologic (

1,

2,

3) and clinical samples (

4,

5) and have used a variety of measures of disability. In a study by Schneier and colleagues (

4), 32 patients with social anxiety disorder showed greater impairment than 14 healthy control subjects on scales specific to social anxiety—the Disability Profile and the Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale. Two reports of data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study also demonstrated impairment in educational status, financial and employment stability, marital status, and social support among persons with social anxiety disorder (

3,

6). Although some impairment may have been due partly to comorbid disorders, even patients with subthreshold social anxiety disorder showed impairment.

Moreover, in a community sample of persons with social anxiety disorder, Stein and Kean (

2) found that comorbid depression contributed only moderately to the dysfunction in daily activities, interpersonal relationships, performance in school, educational attainment, dissatisfaction with a variety of life domains, and poor quality of life associated with social anxiety disorder as measured by the Quality of Well-Being Scale. Three studies have shown that effective treatment improves the quality of life of patients with social anxiety disorder (

5,

7,

8).

Although the utility of quality-of-life scales that are specific to social phobia has been demonstrated (

4), such scales do not allow the broader perspective provided by directly comparing the relative severity of dysfunction across different disorders. Such comparisons may be better accomplished with more widely used general measures, such as the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form-36 (SF-36) (

9). Wittchen and colleagues (

1) found significant impairment on all measures of mental health and on the general health subscale of the SF-36 in a nonclinical population of persons with social anxiety disorder. Their study excluded treatment-seeking patients. As expected, patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders reported even more impairment.

To our knowledge, only one study has directly compared the impact of social anxiety disorder and panic disorder on quality of life (

19). That study showed that patients with social anxiety disorder had greater "life disruptions" than those with panic disorder, but it did not use a validated quality-of-life scale. Schonfeld and colleagues (

20) reported SF-36 scores for patients with previously undetected depression or anxiety disorders diagnosed through a primary care screening procedure. Patients with social anxiety disorder and patients with both panic disorder and agoraphobia were included. Although statistical tests were not used for the comparisons, the patients with panic disorder had more consistent impairment than those with social anxiety disorder.

In the study reported here we further examined the relative effects of social anxiety disorder and panic disorder on quality of life. Quality of life as assessed by the SF-36 was compared between treatment-seeking patients with social anxiety disorder and an age- and sex-matched control group with panic disorder. The scores of the patients with social anxiety disorder were also compared with population-based expectation scores.

Results

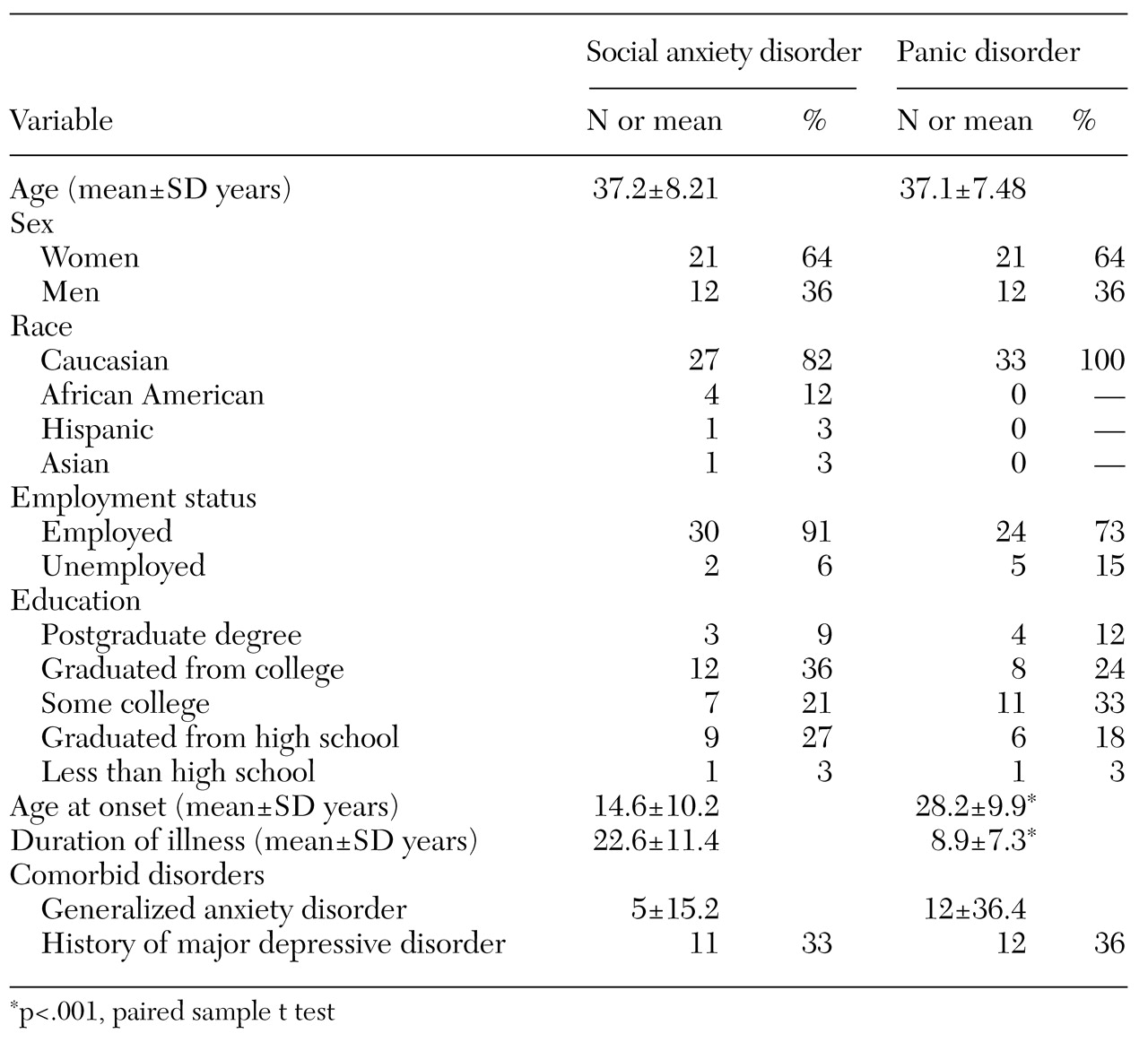

Basic demographic information and morbidity ratings for the two cohorts are summarized in

Table 1. In general, the two cohorts were comparable. The social anxiety group had an earlier age at onset (t=5.39, df=32, p<.001), which is consistent with the natural course of the disorder relative to that of panic disorder (

29). Given that the cohorts were matched for age, the earlier age at onset of social anxiety disorder translates into a significantly longer duration of illness (t=5.58, df=32, p<.001).

In addition, the patients with social anxiety disorder had lower rates of comorbid generalized anxiety disorder, which may reflect the different entry criteria used in the studies from which the cohorts were drawn. Patients with other current comorbid disorders were excluded from the sample of patients with social anxiety disorder, and none of the patients with a history of depression had depression at the time of the study.

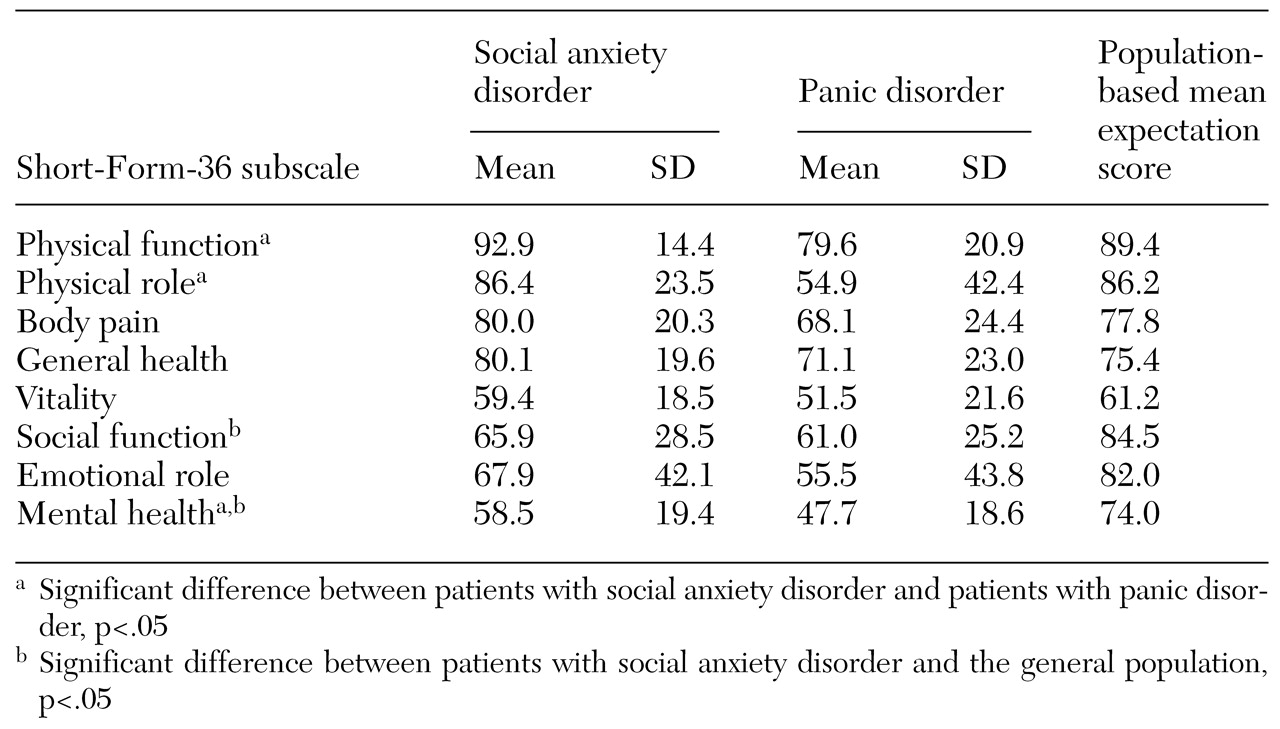

Mean±SD scores on the SF-36 subscales for the two groups are listed in

Table 2, along with population-based means. Compared with the age- and gender-matched general population scores, the patients with social anxiety disorder showed significantly greater impairment in social functioning (t=-3.601, df=32, p<.001) and mental health (t=-4.589, df=32, p<.001); greater impairment in emotional role functioning was also noted, but the difference was not statistically significant. No differences in the four aspects of physical functioning or in vitality were observed between the patients with social anxiety disorder and the general population.

No significant differences were observed between the patients with panic disorder and the patients with social anxiety disorder on SF-36 measures of social functioning or emotional role functioning. However, the patients with panic disorder were significantly more impaired in physical functioning (t=2.88, df=32, p<.01), physical role (t=3.59, df=32, p<.01), and mental health (t=2.6, df=32, p<.05). The patients with panic disorder showed greater impairment on three other scales, but the differences were not significant. The effect sizes were small to medium (d=.35 for body pain, d=.3 for general health, and d=.29 for vitality) (

30). The severity of illness in both groups was in the moderate to marked range as measured by mean±SD scores on the CGI-S (5.1±.65 for social anxiety disorder and 4.72±.73 for panic disorder). Consistent with the findings of Wittchen and colleagues (

1), age at onset and duration of illness were not correlated with scores on any SF-36 subscale.

Discussion

Treatment-seeking patients with social anxiety disorder were significantly more impaired in mental health and social functioning than the general population. They also showed greater impairment in functioning at work and in other daily activities as a result of emotional problems, but the differences were not significant. This level of impairment could not be attributed to the presence of comorbid disorders. However, the patients with social anxiety disorder did not demonstrate impairment on measures of physical functioning or vitality, a measure of energy level and fatigue. In contrast, the patients with panic disorder showed impairment on both physical and psychological measures, which is consistent with the greater somatic focus and physical distress seen in clinical samples of these patients.

The patients with panic disorder showed greater impairment in mental health and vitality than those with social anxiety disorder. No significant difference was observed in social or role functioning. Our findings are in direct contrast with those of Norton and colleagues (

19), who found greater disruption in life circumstances such as employment among patients with social anxiety disorder than among patients with panic disorder.

The results of our study suggest that, at least for patients who do not have comorbid major depression and anxiety, panic disorder may have a greater impact on quality of life than social anxiety disorder. Whereas the somatic symptoms of panic disorder are often prominent and may drive patients to seek treatment, the lack of significant physical impairment among patients with social anxiety disorder and the avoidant nature of these individuals may result in a generally lower degree of help-seeking behavior, especially among those who are the most severely ill.

In the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, only 19.6 percent of persons with social anxiety disorder sought treatment (

29). In the National Comorbidity Study (

31), only 4 percent of persons with social anxiety disorder without comorbid illnesses sought treatment. Among patients who reported significant role impairment, only 28 percent of those with social anxiety disorder sought treatment.

In a study of 9,000 patients who were receiving health care through a health maintenance organization, the prevalence of social anxiety disorder was 8.2 percent (

32). Consistent with the epidemiologic reports cited above, only .5 percent of the affected patients had received a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder from their physician in the previous year, and fewer than a third of those who were diagnosed were receiving treatment. The low rates of treatment seeking among persons with social anxiety disorder contrast with data that suggest that 70.5 percent of persons with agoraphobia who have self-reported role impairment seek treatment (

31).

Furthermore, highly impaired persons with social anxiety disorder may be particularly underrepresented in clinical and research samples because they avoid the social interaction inherent in seeking treatment. Olfson and colleagues (

33) reported that the greatest barriers to treatment for patients with social anxiety disorder were access problems and fear of what others might think or say.

In further support of this hypothesis, Erwin and colleagues (

34) reported that the mean severity of illness of patients with social anxiety disorder who used a Web-based treatment information service was one standard deviation greater than that of patients who visited a clinician's office. Further efforts to increase public awareness of the availability of effective treatments for social anxiety disorder and decrease perceived barriers to treatment seeking among persons who are the most severely affected are warranted.

In addition, in the subset of our social anxiety cohort for whom data were available, the mean age at onset was 14.6 years, compared with 28.2 years for patients with panic disorder. The mean duration of illness was 22.6 years for the patients with social anxiety disorder, compared with 8.9 years for the patients with panic disorder. As Schneier and colleagues (

4) have proposed, social anxiety disorder is a chronic illness with an early onset, and persons who have this disorder may not be able to provide meaningful answers to questions that involve comparing current functioning with an earlier period of normal functioning. Thus Schneier and colleagues suggested that quality of life among these persons may be better assessed with measures specific to social anxiety disorder.

However, even with a more specific scale, the fact that symptoms of social anxiety disorder develop at an early age may contribute to lower expectations about "normalcy" and thus to lower levels of distress and impairment as assessed by any measure that relies on self-reports. The associated failure to recognize that social anxiety symptoms and related impairment represent a disorder that might be improved with treatment may also contribute to the frequent scenario in which patients with social anxiety disorder present for treatment after enduring ten to 20 years of symptoms.

Furthermore, the early onset of social anxiety disorder makes it difficult to project the life course a person might have followed had he or she not become symptomatic. Thus it is difficult to measure the loss of potential productivity or career advancement due to symptoms of social anxiety disorder, although this scenario is reported clinically by some patients. The higher rate of overall employment among those with social anxiety disorder in this study than among the patients with panic disorder may reflect the different effects of each disorder on a person's career path. Patients who develop panic disorder may experience disrupted employment, whereas lifelong social anxiety disorder may be more likely to alter a person's career path. This difference may partly explain the lower impairment among patients with social anxiety disorder than among those with panic disorder.

As with many clinical trials, our protocols mandated the exclusion of subjects with certain comorbid conditions, which produced a social anxiety disorder cohort without significant comorbid illness. In contrast, previous studies of clinical and epidemiologic samples documented high rates of comorbid disorders among patients with social anxiety disorder (

31,

35). Thus our sample probably represents a select and potentially less symptomatic group, which may partly explain why the levels of dysfunction were only moderate. Davidson and colleagues (

3) showed that much of the impairment associated with social anxiety disorder is attributable to comorbid disorders. They proposed that social anxiety disorder without comorbid depression or anxiety may be a milder form of the disorder.

Wittchen and colleagues' study (

1) of a nonclinical sample of patients with social anxiety disorder who were assessed by the SF-36 also demonstrated significantly more impairment among patients with comorbid disorders than among those with "pure" social anxiety disorder. Furthermore, SF-36 scores for this pure sample were similar to those for our sample of patients who had social anxiety disorder without significant current mood or anxiety disorders.

In addition, one hypothesis is that social anxiety disorder, given its early onset, increases the risk that comorbid disorders will develop subsequently. Thus social anxiety disorder may have its greatest adverse impact on function and quality of life through its association with the development of comorbid pathology. The development of complications due to comorbid disorders among patients with social anxiety disorder may thus be preventable if social anxiety disorder is detected and treated early.