After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, there was initially considerable concern that many Americans, including residents of cities that were not attacked, would experience sustained psychological distress, even though their exposure may have been limited to televised images of death and destruction (

1,

2,

3). Surveys of New Yorkers during the second month after the attacks found significantly elevated symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

2,

3); the highest rates were found among residents who were most directly affected by the tragedy.

A recent study of the use of services of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in New York City and elsewhere in the United States in the six months after September 11 found no increase in the use of inpatient or outpatient mental health services among veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD or another mental illness (

11). However, that study did not evaluate differences in either symptom levels at program entry or responsiveness to treatment. To evaluate the continuing impact of the events of September 11 on potentially vulnerable veterans, we examined national VA administrative data that are used to monitor treatment of veterans in specialized intensive PTSD treatment programs. We hypothesized, first, that in the immediate (six-month) aftermath of the events of September 11, veterans who were admitted to such programs would manifest more severe PTSD symptoms, substance use problems, and other behavioral problems than veterans who were admitted in the six months before September 11 or in previous years. Second, we hypothesized that the outcomes of treatment, as measured by changes from admission to an assessment four months after discharge, would be poorer in the immediate aftermath of September 11 than in the previous six months or in previous years.

Methods

Administrative outcomes monitoring

In 1993 a national VA initiative was implemented to monitor clinical outcomes after specialized inpatient, residential, and intensive day treatment programs that provide a combination of medication, psychotherapy, and psychosocial rehabilitation services for military-related PTSD judged too severe for outpatient treatment (

12). Patients admitted to these programs are assessed with a brief, standardized self-report questionnaire at the time of admission and four months after discharge. These questionnaires are completed by veterans in person or, when necessary, over the telephone.

Sample

This study was based on two overlapping samples: 9,640 veterans who had an admission assessment between March 11, 1999, and March 11, 2002, and 6,829 veterans who had a four-month postdischarge assessment during the same period. None of the programs were located in New York City or Washington, D.C., the principal locations of the terrorist attacks.

The mean±SD age of the admission sample of 9,640 was 52.2±5.58 years. A total of 2,743 patients (28.5 percent) were African American, and 528 (5.5 percent) were Hispanic; 4,243 (44 percent) were married, and 4,421 (45.9 percent) were separated or divorced. The patients had completed an average of 12.8±2.01 years of schooling, but only 1,516 (15.7 percent) were employed at the time of admission; 6,499 (67.4 percent) were receiving VA compensation benefits, 4,959 (51.4 percent) specifically for PTSD.

The vast majority (9,176 patients, or 95.2 percent) reported that they had served in a war zone, with 8,980 (93.2 percent) having been exposed to combat fire and 1,992 (20.7 percent) having participated in what they regarded as atrocities. Most patients (71 percent) had been previously hospitalized for a psychiatric or substance use problem, and 5,355 (55.5 percent) had been incarcerated. At admission, 7,056 patients (73.2 percent) were given a diagnosis of PTSD. A total of 3,189 (33.1 percent) had comorbid alcohol abuse, 1,930 (20 percent) had comorbid drug abuse, 1,549 (16.1 percent) had comorbid major affective disorder, and 723 (1 percent) had other psychiatric diagnoses.

Most veterans in the follow-up sample of 6,829 were also in the admission sample and, given that the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at admission were virtually identical between the two samples, these data are not presented here but are available on request from the first author.

Measures

Sociodemographic data obtained at baseline included age, gender, race, marital status, education, history of incarceration, current employment, and receipt of VA compensation for PTSD. Clinical outcomes that were assessed included PTSD symptoms, substance abuse, violent behavior, and employment.

Given their particular significance for specialized PTSD programs, PTSD symptoms were measured in two ways: using the Short Form of the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD, an instrument that has been validated in a large sample of outpatients (

13), and using a four-item PTSD scale developed at the Northeast Program Evaluation Center (the NEPEC PTSD scale) (Cronbach's alpha=.67). The NEPEC PTSD scale had correlations of .61 and .74 with the Short Mississippi Scale at admission and at the four-month follow-up, respectively. These correlations are sufficiently large to indicate that the two scales are measuring the same domain but not so large as to make the scales redundant with each other.

In a study of intensive outpatient treatment of patients with PTSD (

12), the NEPEC PTSD scale and the Short Mississippi Scale had correlations of .63 and .64, respectively, with a continuous PTSD score derived from the SCID PTSD module (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III) (

14). In addition, in an outcome study of intensive inpatient treatment of PTSD (

15), the NEPEC PTSD scale and the Short Mississippi Scale had correlations of .40 and .39, respectively, with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS), a well-validated observer rating scale (

16,

17). The modest magnitude of these correlations most likely reflects the differences between self-report and clinician-administered assessment methods.

Alcohol abuse and drug abuse were measured by using the composite indexes from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (

18), a widely used and well-validated measure of substance abuse outcomes. Violent behavior was measured by using four items that were adapted from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (

19) (Cronbach's alpha=.71). Employment was measured with use of a single question from the ASI that documents the number of days of paid employment in the previous 30 days.

Analyses

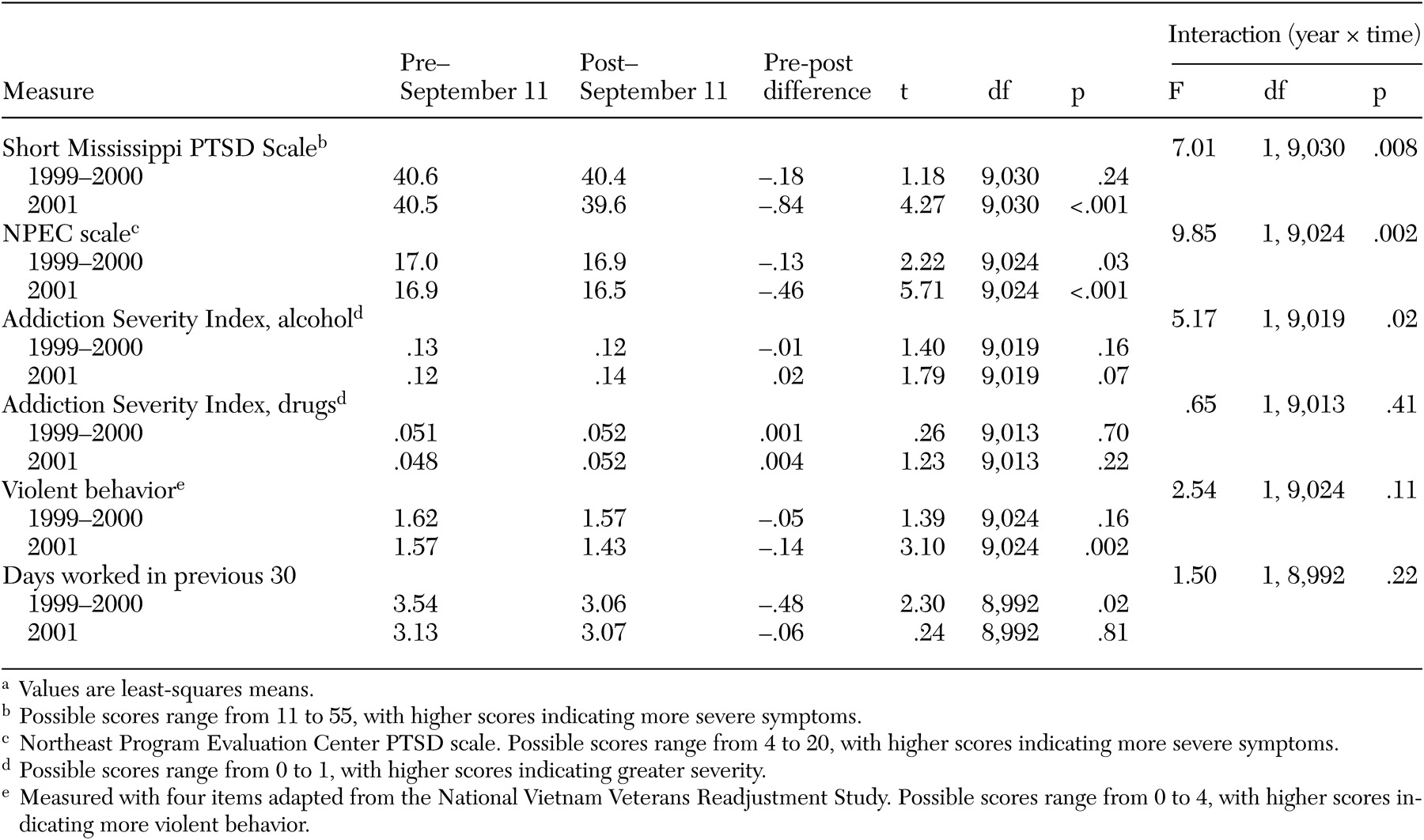

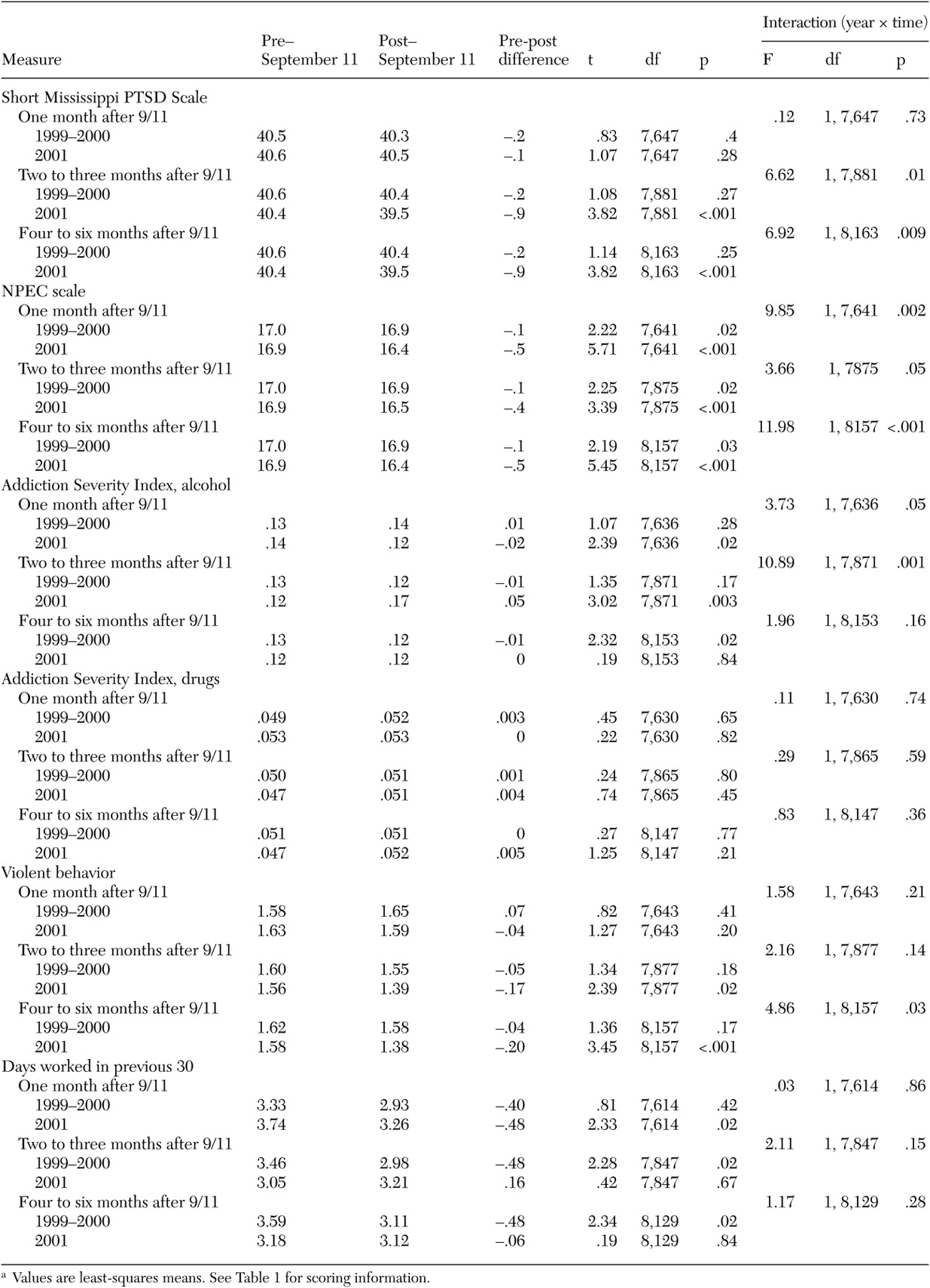

First, two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to evaluate the interaction of time (six months before or after September 11) and year (2001 versus 1999 and 2000). These analyses allowed determination of whether there was a significant difference before and after September 11, 2001—for example, in PTSD symptoms at admission—and of whether these differences were significantly different from those observed among patients admitted during the two previous years. These analyses were then repeated for veterans who were admitted during each of three time intervals: one month, two to three months, and four to six months after September 11.

Because differences in other baseline measures had the potential to confound these analyses, we conducted a preliminary series of two-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs), as described above, to identify all baseline measures that were different before and after September 11, 2001, in ways not observed in previous years. Measures of sociodemographic status, military experience, and past service use were examined in this fashion, in addition to measures of clinical status, community adjustment, and the number of days between discharge from an intensive program and completion of the follow-up interview. Measures for which interactions were significant were included as covariates in all subsequent analyses. Veterans in the post-September 11 follow-up sample were younger, had relatively more comorbid psychiatric illness, reported less exposure to combat fire, and had a longer interval between discharge and the follow-up assessment.

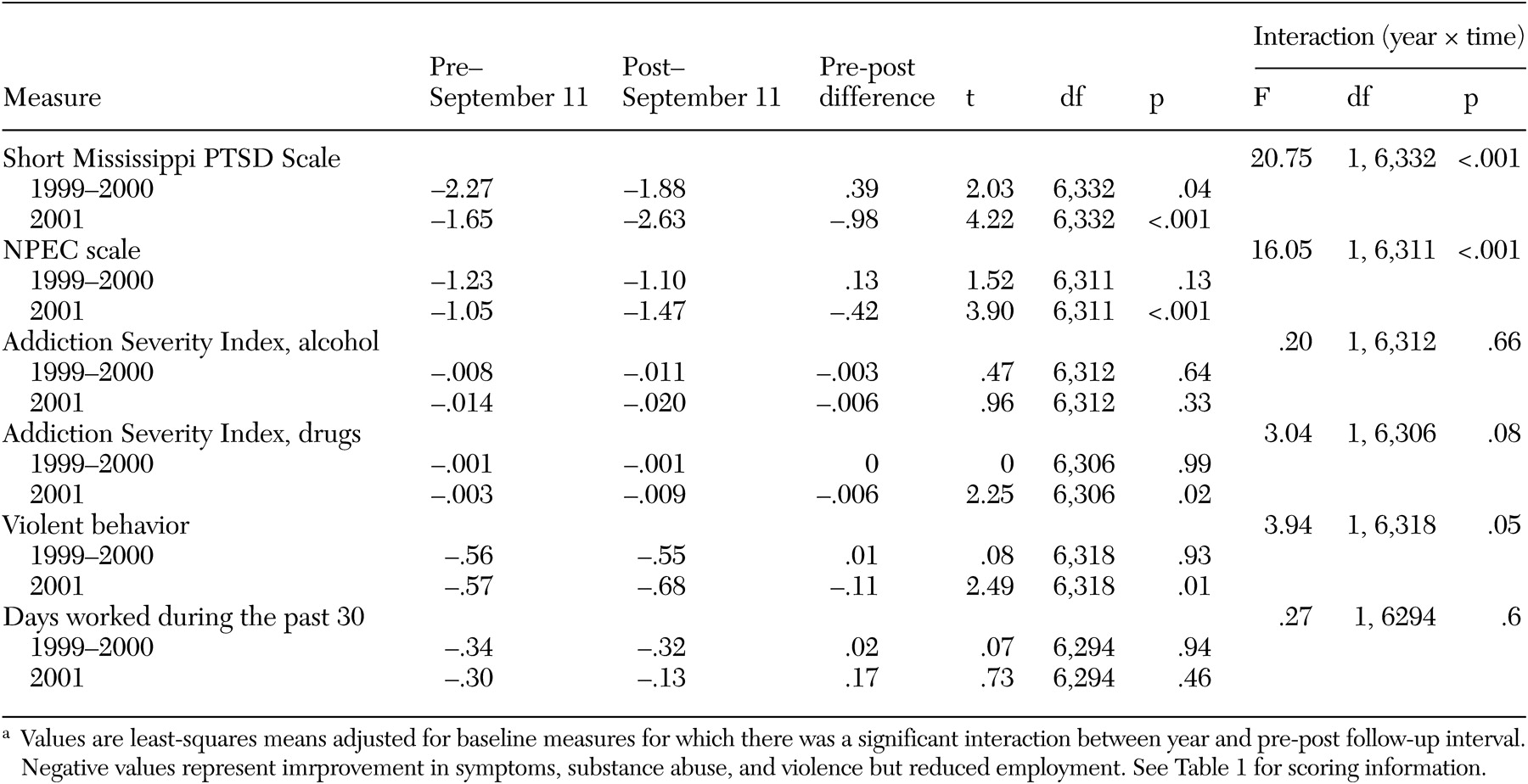

A second set of two-way ANCOVAs were then used to evaluate differences in the amount of clinical improvement observed before and after September 11 and to determine whether the observed patterns differed from those of previous years. Clinical improvement in these analyses was measured as the difference between the follow-up assessment and the admission assessment. Because the amount of improvement is likely to be inversely related to admission ratings—for example, patients with higher symptom levels are likely to show greater reductions in symptoms over time, because they have more room to improve—we included the baseline value of the change score as an additional covariate in all of these analyses.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study we examined data on mental health status at admission and clinical improvement among veterans who were treated in specialized intensive VA PTSD programs before and after September 11, 2001, and, for comparison, during 1999-2000. On the basis of previous studies, we expected that these populations, which have been judged as requiring intensive—in most cases, hospital-based—treatment, would be vulnerable to retraumatization as a result of the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C., and would experience more severe symptoms at admission and less clinical improvement. Neither of these hypotheses was supported by the study. Rather, in direct contrast, symptom levels at admission appeared to decrease after the terrorist attacks and improvement in symptoms to increase.

It is especially notable that the most robust association in relation to the events of September 11 was for PTSD symptoms, both at admission and from admission to the four-month postdischarge follow-up assessment. In some instances, similar findings were observed for alcohol problems and violent behavior, but these results were not nearly as consistent across time intervals or as robust in their statistical significance as the effects on PTSD symptoms, such as nightmares, sensitivity to loud noises, and numbness of feelings.

The association with clinical improvement was strongest in the first month after September 11 and attenuated with time, much like the reactions observed in the general public, albeit in the opposite direction. Thus although symptoms in the general public peaked right after the attacks and declined in the following months (

1,

2,

3,

20,

21), improvement in symptoms in our VA sample was greatest during the first month after September 11 (-2.2 points on the Short Mississippi Scale and -1.01 points on the NEPEC scale) and was less dramatic four to six months after September 11 (-.50 points on the Short Mississippi scale and -.17 points on the NEPEC scale).

Although it is unambiguously clear from these data that there was no exacerbation of symptoms or reduction in improvement in this population after the attacks of September 11, it appears that the events of September 11 may, in some way, have had a small but beneficial effect on PTSD symptoms among these severely ill veterans. To better understand the specific areas in which there was greater improvement, we repeated our analysis to examine each of the items that constitute our two measures of PTSD symptoms. We found significantly greater improvement on 12 of the 15 items. The three items that did not show a significant change were either infrequently endorsed ("I feel like killing myself") or reverse coded ("I sleep well," "I enjoy the company of other people") and were perhaps confusing to the respondents. Thus the increase in improvement of PTSD symptoms was relatively global.

We speculate that three factors, unique to the period immediately after the attacks of September 11, may have accounted for these statistically significant findings: an increased sense of community, patriotism, and national pride; the "normalization" of PTSD-like reactions to the terrorist attacks by the media; and the personal experience of mastery and competence that veterans who had long dealt with PTSD may have felt during this time.

During the period after the September 11 terrorist attacks, many Americans experienced a unique sense of community and intensified patriotism based on the feeling that everyone was vulnerable together. Distinctions of wealth, occupational prestige, and race as well as competitive strivings that normally preoccupy and divide people receded before a threat that vilified and targeted the entire nation simply for being American. Many veterans felt enobled by the patriotic ambience and honored as heroes who had made sacrifices for their country in the past.

There was also much discussion of PTSD in the media in the aftermath of September 11, and—as evidenced by the surveys conducted in the ensuing months (

1,

2,

3)—many people, even those who were not directly affected by the attacks, experienced psychological distress. During that period PTSD became a "normal" reaction to something experienced by everyone. To the extent that veterans with severe PTSD feel isolated, stigmatized, or excluded from mainstream life because of their symptoms, the period after September 11 may have been one in which they experienced special feelings of inclusion and acceptance.

Anecdotal reports from VA clinics suggest that some veterans, far from being overwhelmed by the horrific destruction, experienced feelings of familiarity, mastery, and competence as survivors who had been exposed to horror in the past but who had experience in coping with the resultant painful memories. It has been reported that when the staff in these programs expressed unusual distress and apprehension after the terrorist attacks, veterans mobilized themselves to be helpful during a difficult time. Because the follow-up interviews were conducted months after the completion of treatment, it is also likely that these veterans were able to rally their emotional resources in response to the fear and apprehension of family members or acquaintances.

It is also important to consider whether these findings might reflect one or more artifacts of reporting or data collection. For example, it is possible that the veterans who were evaluated at admission or at follow-up in the six months after September 11 were systematically different in some ways from those who were evaluated previously. We identified some differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between earlier samples and the post-September 11 admission and follow-up samples, most notably less war zone exposure in the post-September 11 samples, but these differences were small (3 to 5 percent), and adjustment was made for them by using multivariate techniques in our analyses. A previous study (

11) found no change in inpatient or outpatient use of VA services during this period, which suggests that differences in the volume or general pattern of VA mental health service delivery would not explain our findings.

Another limitation of this study was that follow-up rates were consistently lower than one would find in a research study, although they were higher than those in other outcome-monitoring efforts (

22). In addition, the measures were generally brief and were administered by program personnel rather than by trained independent research assistants. However, these limitations are not likely to have produced the pattern of statistically significant differences we observed after September 11.

Major advantages of this study are that it used a large data set based on a national sample of veterans residing outside of the New York City and Washington, D.C., areas and that standard methods of data collection were used throughout the entire period. Other studies of combat veterans have identified benefits as well as hardships that derive from war zone trauma (

23), and the observations reported here of lower levels of PTSD symptoms after September 11 at admission and at follow-up attest to the unprecedented psychological and social impact of the events of that day.