Population-based studies have tended to focus on the use of mental health services among persons with a psychiatric diagnosis. In this study, we capitalized on data from a recent national survey to determine population estimates of co-occurring mental syndromes and substance use problems and the use of substance abuse services and to examine correlates of service use. We were particularly interested in the extent to which the co-occurrence of mental syndromes and substance use problems was associated with the use of substance abuse services.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the 16,661 adults in the 1997 NHSDA sample are summarized in

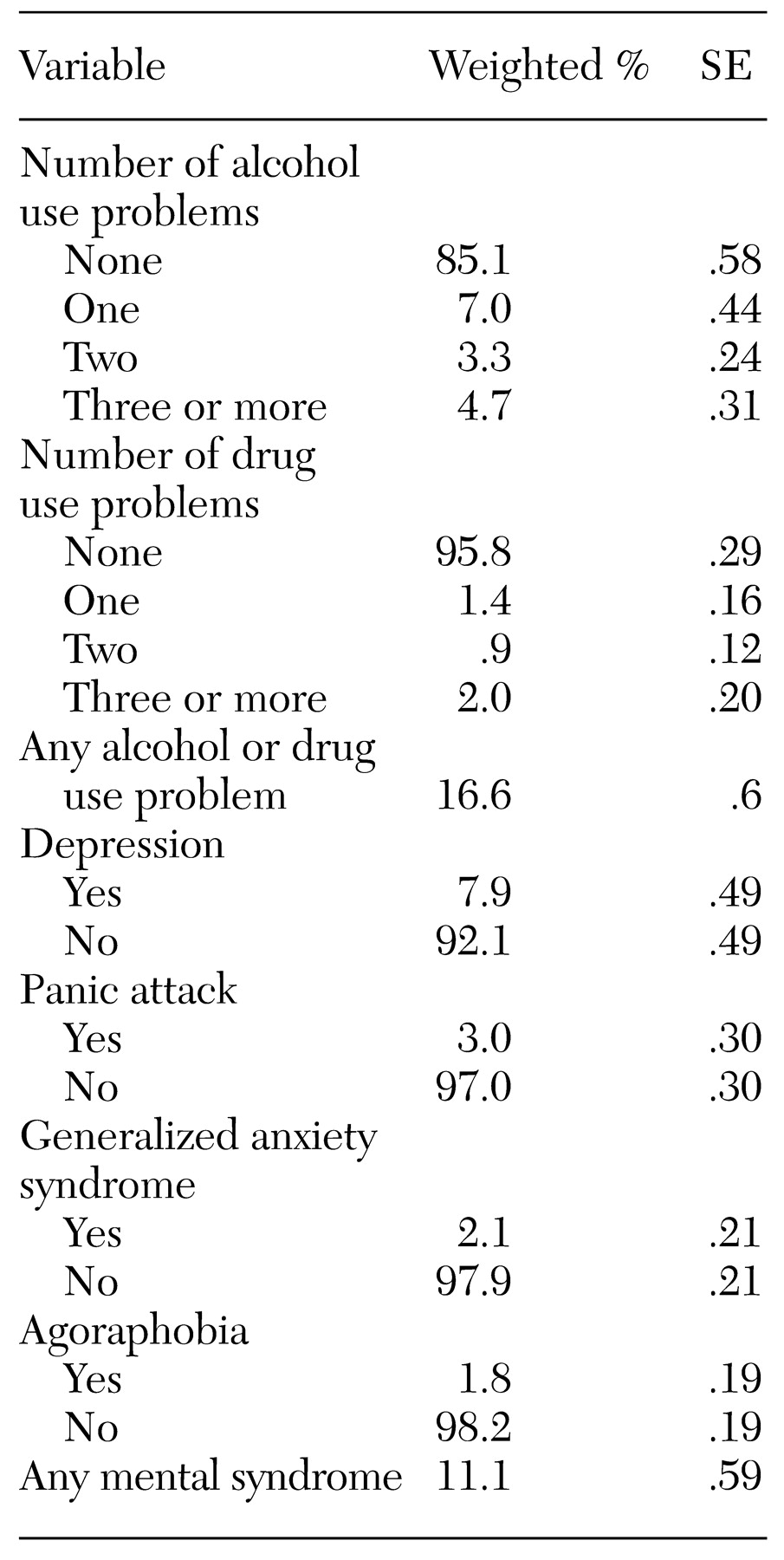

Table 1. Prevalence estimates of mental syndromes and substance use problems are given in

Table 2. Approximately 15 percent of all adults reported at least one alcohol use problem, and 4 percent reported at least one drug use problem. Altogether, 3,474 (17 percent) reported at least one alcohol or drug use problem in the year before the survey. Close to 2 percent of the respondents—or 6 percent of those who had at least one alcohol or drug use problem—reported receiving any substance abuse service for their use of alcohol or illicit drugs in any setting in the previous year. Only .8 percent of those with no substance use problems received such services in the previous year.

Overall, 1,929 respondents (11 percent) reported at least one of the four mental syndromes in the previous year. The syndrome with the highest prevalence was depression (8 percent). Close to 5 percent of all respondents, or 23 percent of those with at least one mental syndrome, reported receiving treatment from specialty sectors for mental health problems in the previous year.

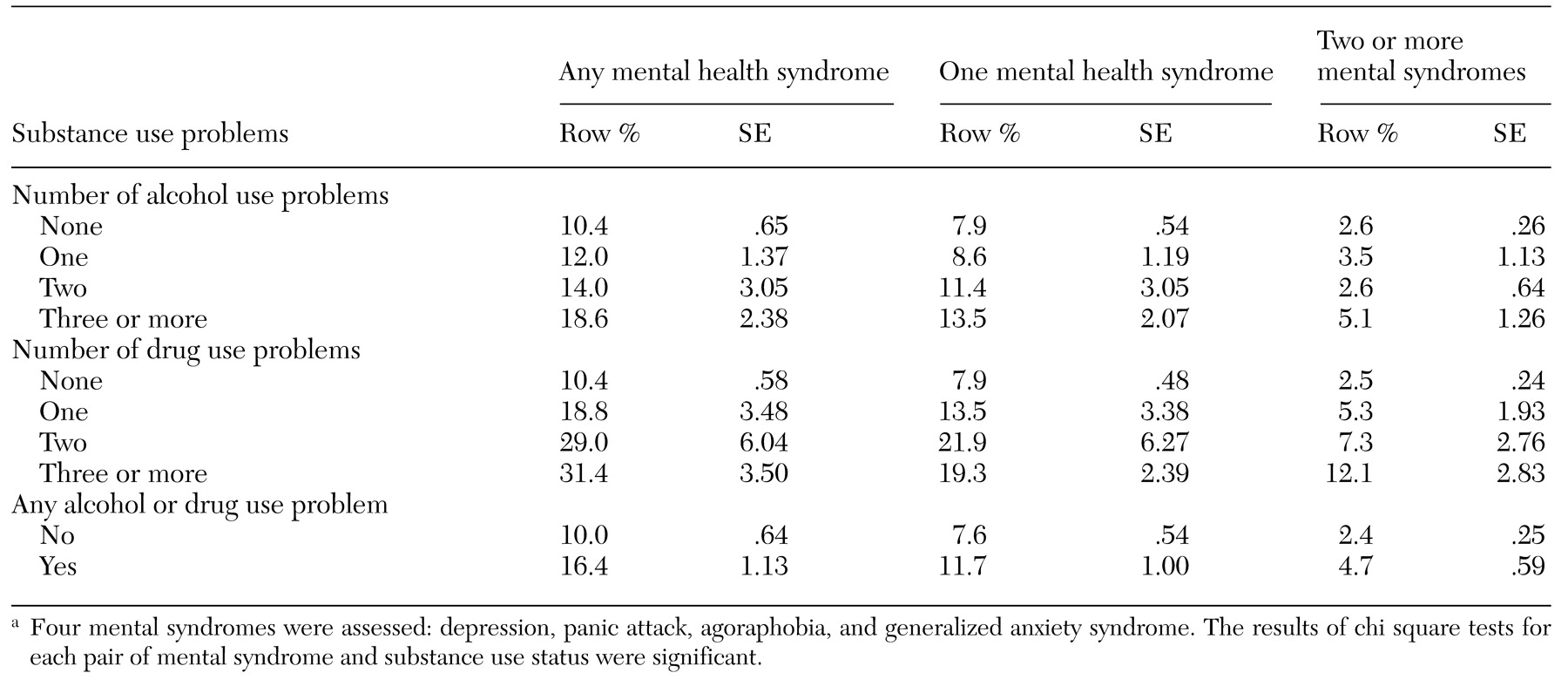

One-year prevalence estimates of mental syndrome by substance use status are shown in

Table 3. Significantly higher rates of mental syndromes were noted among persons who reported any substance use problems than among those who reported no problems; those who reported at least three substance use problems were particularly likely to report a mental syndrome. For example, 10 percent of persons with no alcohol use problem reported having at least one mental syndrome, compared with almost 19 percent of those with at least three alcohol use problems. Similarly, one in ten persons with no use drug use problems reported having at least one mental syndrome, compared with about three in ten who had at least three drug use problems.

Prevalence estimates of substance abuse service use among adults with at least one alcohol or drug use problem are given in

Table 4. Significant bivariate associations were observed between use of substance abuse services and each of the variables related to alcohol or illicit drug use problems, mental syndromes, and past-year use of mental health services. Persons who reported three or more drug use problems were much more likely to use substance abuse services than those who reported fewer or no problems. A very low prevalence of service use (3 percent) was noted for respondents who reported having alcohol use problems only.

The co-occurrence of mental syndromes and substance use problems proved to be highly associated with help-seeking behavior; 13 percent of substance-abusing respondents who reported depression used substance abuse treatment services, compared with 5 percent who did not report depression. Similarly, co-occurring panic attack and the presence of generalized anxiety syndrome and agoraphobia were each strongly associated with higher rates of substance abuse service use among substance-abusing persons. The number of mental syndromes reported by individual respondents was also strongly associated with use of substance abuse services. In addition, persons with substance abuse who recently received treatment for mental health problems were much more likely to use substance abuse services during the same one-year period.

The final logistic regression model assessed whether the association between use of substance abuse treatment services and mental health and substance use variables was independent of demographic characteristics. The results are summarized in

Table 5. The model included significant correlates found in the bivariate analysis—race or ethnicity, educational level, employment status, and marital status—as well as age, gender, alcohol or drug use problems, mental syndromes, and use of mental health services.

This adjusted model showed that men were twice as likely as women to seek services. Compared with white persons, American Indians and Alaska Natives were much more likely and Asians and Pacific Islanders were much less likely to use substance abuse services. Level of education was strongly and inversely associated with service use. Persons with substance use problems who worked full-time were much less likely to use services than those who did not work full-time. Neither age nor marital status was related to service use.

With statistical adjustment for these specified demographic characteristics, the reported number of drug use problems (but not alcohol use problems) was strongly associated with service use. Again, recent use of mental health services was strongly associated with use of substance abuse services. Persons who reported one coexisting mental syndrome were about two times as likely to seek substance abuse services as those who did not report a coexisting syndrome.

Discussion and conclusions

We examined the co-occurring mental syndromes and substance use problems and factors related to the use of substance abuse treatment services in a national sample of adults. We found that 9 percent and 4 percent reported at least one DSM-IV alcohol or drug use problem, respectively, in the previous year. Overall, 11 percent of the respondents reported at least one of the four NHSDA-specified mental syndromes in the previous year—depression, panic attack, agoraphobia, or generalized anxiety syndrome. Approximately one-third of respondents who had at least three drug use problems also reported at least one mental syndrome during a one-year period. Almost one-fifth of respondents who had at least three alcohol use problems also reported at least one mental syndrome.

The use of substance abuse treatment services among persons with one or more coexisting mental syndromes was estimated at 16 percent, whereas only 4 percent of those without a coexisting mental syndrome received services. Adjusted logistic regression analyses of data from respondents who reported at least one alcohol or drug use problem indicated that the use of substance abuse treatment services was associated with the presence of drug use problems (but not alcohol use problems), coexisting mental syndromes, and recent use of mental health treatment services.

The study design had some limitations. First, the NHSDA uses a cross-sectional design, so causality cannot be inferred. Our analyses were based on self-reported data, which may be affected by recall bias, memory errors, and respondents' reluctance to answer sensitive questions. Both mental health and substance use problems may have been underreported. Second, the sampling frame of the NHSDA is limited to civilian, noninstitutionalized persons. Higher rates of drug use have been observed among homeless persons and individuals living in institutional group quarters (

20).

Third, assessments of self-reported mental syndromes were restricted to the four syndromes specified in the NHSDA. Fourth, the lack of assessments related to the withdrawal criterion for substance dependence is likely to have underestimated substance use problems, particularly the prevalence of alcohol dependence—that is, persons who reported three or more symptoms of dependence. Although withdrawal is one of the specified criteria for the

DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol dependence, the diagnosis of marijuana dependence does not specify the presence of withdrawal (

16), the most common illicit drug of dependence in the general population (

21). Nevertheless, our focus on self-reported substance use problems as defined by

DSM-IV may have missed some persons with substance use problems who needed services but who reported no problem, perhaps denying that they had a substance use problem or believing that their substance use was under control (

22).

Finally, the survey questions that tapped use of substance abuse treatment services cast a much wider net than those that assessed mental health treatment. For example, substance abuse services included self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, and other social services, whereas mental health services were restricted to services delivered by specialty providers. Because of this broad definition of substance abuse services, our estimates of substance abuse service use are based on adults who reported one or more alcohol or drug use problems. Our analyses might also have identified some subgroups who did not perceive the need for such services. Nevertheless, these estimates of co-occurrence represent an advance over those based on clinical samples, which may yield inflated estimates given that persons who have multiple ailments are more likely to seek treatment (

23).

Perhaps the most salient finding of this study concerns the proportion of adults in the general population who reported at least one DSM-IV substance use problem—almost one in six—and the very small number of them who received any substance abuse service. This finding must be tempered with the recognition that the presence of a solitary problem may not constitute sufficient reason for seeking help. On the other hand, the definition of substance abuse services as operationalized by the NHSDA is sufficiently wide to capture a variety of nonclinical settings, including self-help groups.

This finding thus speaks convincingly to the need for primary health care providers or family physicians to conduct routine screenings for substance use problems, to make referrals to prevention or treatment specialists as appropriate, and to follow up on these referrals and their effects on subsequent visits. The finding also suggests that purchasers of health services in the public and private sectors who are truly interested in the well-being of those covered by their policies should induce the managed care organizations with which they do business to support these practices.

Our results also indicate that some subgroups may need substance abuse services but not receive them, including women, Asians and Pacific Islanders, college graduates, persons who are employed full-time, persons with alcohol abuse only, and persons with substance abuse who report no coexisting mental syndromes. These findings suggest that these subgroups should be targeted by prevention specialists' outreach efforts. More research is needed to examine the nature and extent of barriers to substance abuse treatment.

Also of interest is the much lower use of substance abuse services by substance abusers who did not report a mental syndrome or use of mental health services. This finding, which is similar to that reported by the NIMH-ECA (

3) and others (

9,

24), suggests that help-seeking behavior may be less stigmatized for persons with mental health syndromes than for those with substance use problems alone. It is also possible that, relative to substance abuse services, mental health services are more available or more easily reimbursed. We may also conjecture that persons with a dual diagnosis may be more in need of services than those with a substance use disorder alone, because their substance abuse may be more severe or may be exacerbated by mental illness (

25).

It is also possible that persons with substance use problems who seek or receive services are—or become—more aware of their mental health problems and thus are more likely to report them retrospectively. If this hypothesis is correct, receipt of substance abuse services may tend to generate a dual diagnosis even among persons with discrete substance use or mental disorders (

26). Of course, outside of a prospective study, the causal relationships between substance use and mental health problems and the processes by which an understanding of one may lead to recognition of the other cannot be disentangled (

26).

Overall, our findings indicate that the severity of substance use problems plays a significant role in help seeking. It appears that many persons with substance use problems received no help until multiple substance use or other mental health problems affected their daily life. Delaying help seeking might have a negative impact on the course of substance abuse or might lead to the development or exacerbation of a comorbid mental disorder and increase health care costs. If behavioral health care systems were designed to increase access to early prevention and treatment interventions for persons with substance use problems, the rate of comorbidity and the cost of treating problems related to substance use might be lower.

The results of this study have several additional implications. First, the nature and pathways to use of alcohol treatment services deserve more focused investigation. Although alcohol use problems are more prevalent than other drug use problems, persons with an alcohol use problem alone were not likely to use substance abuse services. Because of societal sanctions and cultural norms of alcohol use, some adults with alcohol use problems might not perceive their alcohol use behaviors as problematic. Studies need to identify factors that enhance or impede the likelihood of service use, particularly among the underserved populations we identified. Some of these factors may be related to specific cultural or gender issues, whereas others may be linked to perceived stigma, attitudes toward treatment services, service availability, costs, and accessibility.

Second, primary health care and prevention providers should also be aware that persons with substance use problems who do not also report or manifest mental problems may be less visible and thus more likely to be undetected and underserved. Primary health care providers should be trained to detect substance use problems and refer patients with these problems to appropriate services. Finally, our findings suggest the need to develop and implement strategies to increase the use of treatment services among persons with substance use problems.