Schizophrenia, a devastating chronic mental disorder affecting nearly 1 percent of the U.S. population, is characterized by psychotic symptoms that often result in hospitalization (

1,

2). Relapses of acute symptoms are common and have been estimated to result in costs to the U.S. health care system of almost $2.3 billion annually (in 1993 dollars) (

3). The social burden is higher still, because most patients with schizophrenia are unemployed (

4).

Until recently, the management of the symptoms of schizophrenia relied on the use of a number of conventional antipsychotic agents, such as haloperidol and chlorpromazine. These drugs are relatively effective in controlling symptoms but often produce adverse effects, especially extrapyramidal symptoms and, less commonly, tardive dyskinesia (

5). Poor tolerability is thought to be associated with nonadherence to therapy, which is a significant problem for patients with schizophrenia. Adverse events are among the more common reasons cited for poor compliance with conventional antipsychotic therapy or for discontinuation of conventional antipsychotics (

6,

7,

8,

9,

10). Medication nonadherence is the best predictor of relapse after a psychotic episode (

6) and thus is an important clinical and public health issue.

Previous studies documented low rates of medication adherence among patients with schizophrenia who use conventional medications. In one study, patients receiving conventional antipsychotics filled prescriptions for an average of 50 percent of prescribed doses, with a range from 20 to 90 percent (

11). In another study, only 11 percent of patients with schizophrenia who were receiving conventional agents achieved uninterrupted therapy; the mean duration of uninterrupted therapy was 142 days over a year (

12).

More recently, a new class of agents —the atypical antipsychotics—has been introduced. These medications are potentially more efficacious than conventional antipsychotics and have a lower incidence of central nervous system adverse effects, such as tardive dyskinesia (

13,

14). The first drug in this class, clozapine, was introduced in the 1970s. Although clozapine is associated with greater efficacy compared with conventional antipsychotics (

14), the potential for serious hematologic side effects and the requirement for weekly monitoring for such effects have limited its clinical use. In the past several years, other atypical antipsychotics—risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone—have been introduced in the United States.

Limited data are available for comparing the medication adherence associated with atypical agents versus conventional treatment. In one study, prescription refill records for an eight-month period were analyzed to investigate compliance with various classes of antipsychotic medication (

15). Forty-four and 48 percent of patients continued to refill their prescriptions for atypical and conventional antipsychotic agents, respectively. However, this study had several shortcomings, especially a lack of medical claims data that would have allowed identification of the underlying diagnosis for which the medications were prescribed. In this instance, the results of the study may have been affected by differential prescribing of atypical versus conventional antipsychotics for certain diagnoses, such as dementia, acute psychoses, and depressive psychoses, that do not warrant long-term treatment.

To further explore adherence to antipsychotic therapy, we undertook a retrospective analysis of linked pharmacy and medical claims data for patients with schizophrenia in the California Medicaid ("Medi-Cal") program who were initiating therapy with an antipsychotic medication. In late 1997, Medi-Cal removed restrictions on the use of atypical antipsychotics, thus providing an ideal opportunity to evaluate adherence to alternative therapies under typical practice conditions, including equivalent access to all antipsychotic medications.

We focused on three questions. First, how do the characteristics of patients who receive conventional antipsychotics compare with those of patients who receive atypical antipsychotics? Second, are rates of therapy switching and discontinuation different among users of the two types of medication? Third, does prescribing of concomitant psychotropic medications differ between these two groups of patients?

Methods

Data source

This study was based on data on eligibility and paid medical and pharmacy claims for a 10 percent random sample of Medi-Cal recipients. Medi-Cal, which covers more than 7 million persons, is the largest state Medicaid program in the United States. Total expenditures for the program exceeded $14 billion in 1998 (

16). Many types of health care services are covered by the program. In 1998 (

16), the most expensive services included hospitalization ($2.5 billion), nursing home care ($2.2 billion), physician services ($.7 billion), and prescription medication ($1.6 billion) (

16).

This analysis was based on data on eligibility and paid claims for prescription drugs, inpatient medical services, and outpatient medical services. The claims data for prescription drugs included National Drug Code numbers, dispense dates, quantities of medication dispensed, and number of days supplied. Inpatient medical services contained a primary diagnosis, up to two secondary diagnoses in

ICD-9-CM (

17) format, and dates of admission and discharge, while outpatient medical services included the primary diagnosis and service date. The eligibility file included age and gender as well as a monthly history of Medi-Cal eligibility. The data used in this study were obtained for the period from 1996 to 1998.

Patients

The patients included in this study met the following eligibility criteria: age of 18 years or older; initial receipt of oral monotherapy with a conventional or atypical antipsychotic as an outpatient between October 1 and December 31, 1997 (the index period, with the first dispense date denoting the index date); no prescriptions for the same medication in the preceding year; a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM codes 295.0x through 295.6x and 295.8x through 295.9x) or schizoaffective disorder (ICD-9-CM code 295.7x) listed on a medical claim in the year before the index date; and continuous Medi-Cal eligibility from one year before to one year after the index date. We chose to focus on patients who were starting a new medication—those who had not taken an antipsychotic medication or had taken a different agent in the previous year—rather than those who continued to take the same drug, because the rate of adherence to therapy may have been artificially high in the latter group.

Patients were assigned to cohorts on the basis of the first new agent they received during the index period. For atypical antipsychotic agents, we focused on risperidone and olanzapine, the most widely used agents in the class during the study.

Study measures

Treatment discontinuation and switching. Patients who discontinued the medication they had first received during the index period were identified on the basis of having no record of a prescription refill for that medication in the last six months of the one-year follow-up period. For those who discontinued medication, we also determined whether their treatment was switched to another antipsychotic agent or whether the patient discontinued use of all antipsychotics. Patients who discontinued use of all antipsychotics were identified on the basis of having no record of a prescription refill for any antipsychotic in the last six months of the follow-up period.

Persistence with therapy. Treatment persistence was assessed in terms of the number of covered days—that is, the number of days the medication was available—over the course of the one-year follow-up period.

Use of selected concomitant medications. The use of concomitant therapies was evaluated before and after the start of the medication initiated during the index period. The concomitant therapies of interest included antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers, and anticholinergics for the treatment of extrapyramidal side effects. We assessed changes in the number of patients who received each specific concomitant medication between the baseline and follow-up year.

Data analyses

Descriptive analyses were undertaken to evaluate differences in characteristics between patients receiving conventional antipsychotics and those receiving atypical agents as well as differences in doses of atypical antipsychotics. We estimated the likelihood of discontinuation and therapy switching on both an unadjusted and adjusted basis. The unadjusted analysis used chi square tests, and the adjusted analysis was based on logistic regression analysis. In the multivariate analyses, the independent variables included age, gender, additional psychiatric diagnoses, type of antipsychotic medication initiated during the index period (conventional or atypical), whether antipsychotics had been prescribed in the previous 12 months, the number of unique medications prescribed in the previous 12 months, and hospitalizations in the previous year (none versus one or more). The use of concomitant medications during the follow-up period was assessed with logistic regression that controlled for the independent variables listed above as well as whether these medications had been prescribed in the previous 12 months. Medication persistence was evaluated with t tests and multivariate analyses of covariance with the same set of predictors. The analyses of data were conducted by using PC SAS Version 8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Patients' characteristics

A total of 9,853 patients were treated with a conventional or atypical antipsychotic between October 1, 1997, and December 31, 1997. A total of 7,989 of these patients (80 percent) were excluded from the analysis because they were continuing with a previously prescribed therapy. An additional 1,566 patients were excluded because they were receiving a combination of agents (N=427), were not adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder eligible for the entire study period (N=1,071), or had recently been hospitalized (N=68). The remaining 298 met all inclusion criteria. Of these, 93 received a conventional antipsychotic and 205 an atypical antipsychotic.

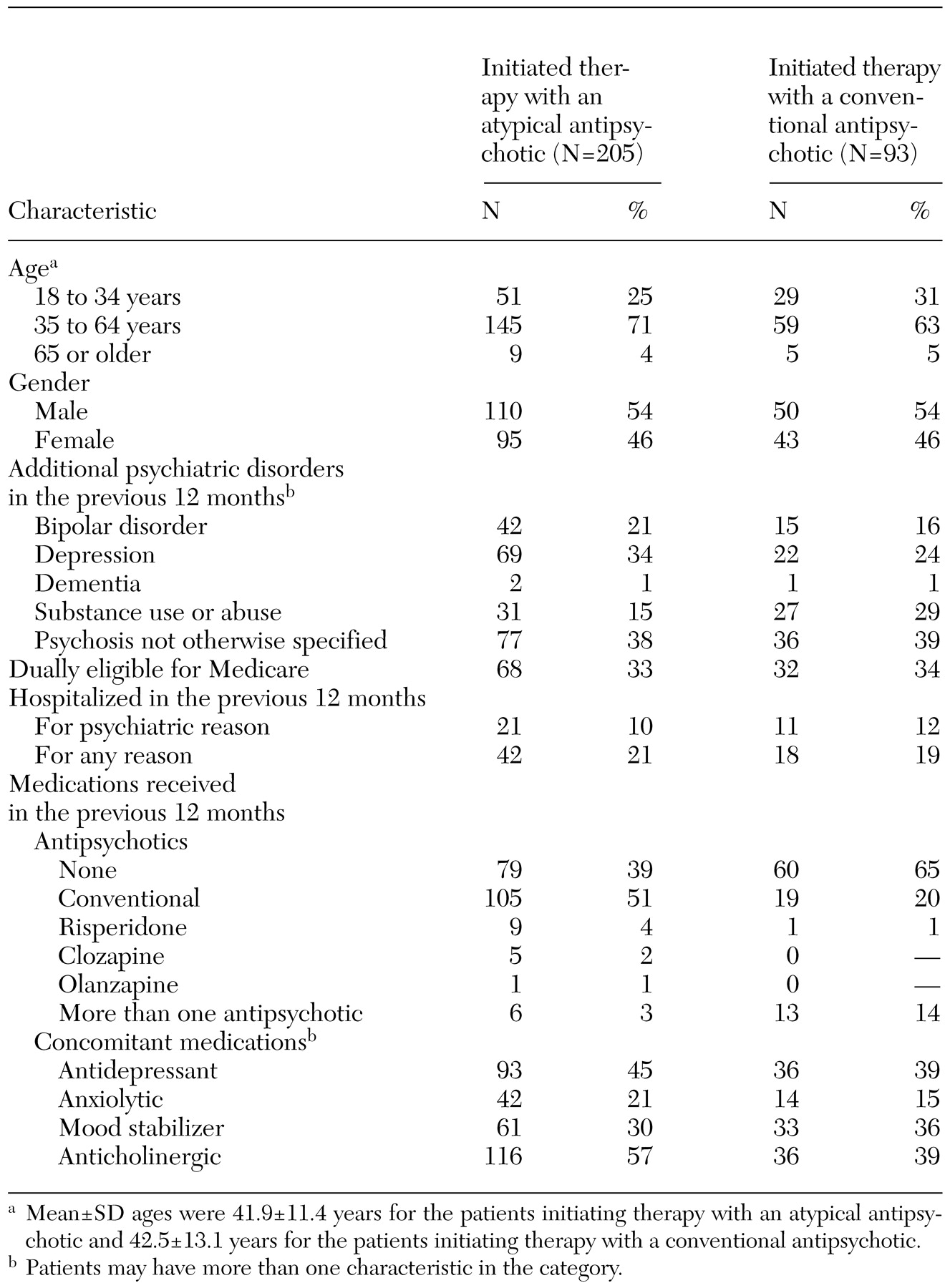

The two groups of patients were similar demographically (

Table 1). Both groups had a mean age in the early 40s, and slightly more than half of the patients were men. However, the groups differed in distribution of additional psychiatric diagnoses; bipolar disorder and depression were more common among the patients starting atypical antipsychotic therapy, and substance use or abuse was more common among the patients starting conventional antipsychotic therapy. Moreover, approximately two-thirds of the patients for whom conventional therapy was prescribed (N=60) were not treated with antipsychotics in the previous year, compared with about 40 percent (N=79) of those receiving atypical antipsychotics. Most patients who received atypical agents were starting these medications as a result of a switch from conventional medications. In the atypical antipsychotic group, previous use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and anticholinergics appeared to be more common than previous use of anxiolytics. The initial mean±SD daily doses of risperidone and olanzapine were 3.8±2.0 mg and 10.4±5.0 mg, respectively, and the final mean±SD daily doses were 4.0±1.9 and 12.8±5.5 mg, respectively.

Treatment discontinuation and switching

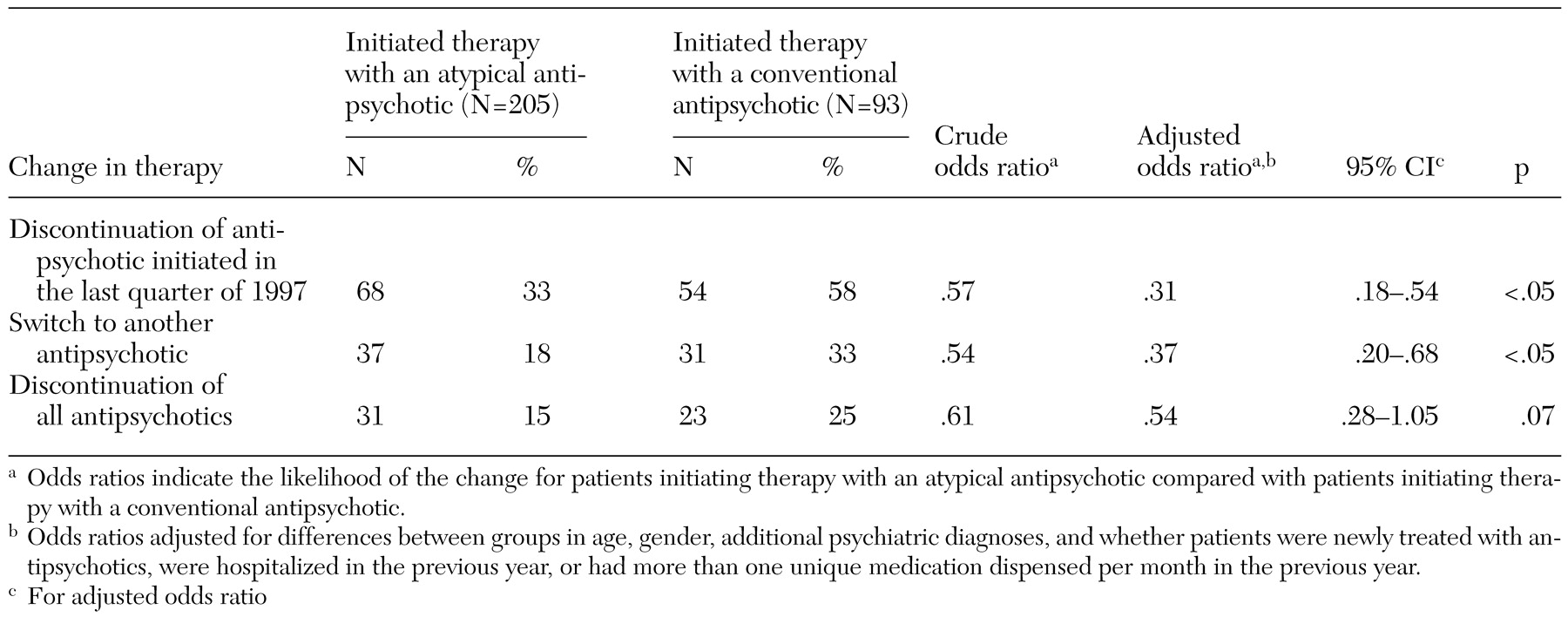

Over one year, 58 percent (N=54) of the patients who initiated therapy with a conventional antipsychotic discontinued the medication, compared with 33 percent (N=68) of those who initiated therapy with an atypical antipsychotic (

Table 2). Many of these patients went on to receive a different antipsychotic medication. The medication of one-third of the patients who initially received a conventional antipsychotic was switched, compared with the medication of 18 percent of those who initially received an atypical antipsychotic. Users of atypical antipsychotics were about a third as likely to have a switch in therapy as users of conventional antipsychotics (adjusted odds ratio [OR]=.37, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=.20 to .68). Factors associated with significantly less treatment switching included a recent psychiatric-related hospital stay and receipt of antipsychotic medication in the previous 12 months. A diagnosis of substance use or abuse was positively associated with therapy switching.

The proportion of patients who discontinued treatment with all antipsychotics was lower among these who initially received an atypical antipsychotic than among those who received a conventional antipsychotic (adjusted OR=.54, CI=.28 to 1.05), but this difference was not significant.

Persistence with treatment

The adjusted mean percentage of covered days was 58 percent for the patients who received conventional antipsychotic therapy and 61 percent for those who received atypical antipsychotics. Factors associated with a significantly lower rate of persistence included being older (65 years or older), having an additional diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and newly starting an antipsychotic medication.

Use of concomitant medications

Compared with use of conventional antipsychotics, the use of atypical antipsychotics was associated with a significantly lower likelihood of receiving concomitant anxiolytics (adjusted OR=.44, CI=.23 to .86, p<.05) and anticholinergics (adjusted OR=.15, CI=.08 to .31, p<.05). The factors associated with a significantly lower rate of use of concomitant therapy included being female and not having an additional diagnosis of depression of substance use or abuse. Patients who received atypical antipsychotics were also less likely to use concomitant antidepressants and mood stabilizers, but these differences were not significant.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated antipsychotic treatment discontinuation and switching, medication persistence, and changes in the use of selected concomitant medications among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who received conventional or atypical antipsychotic agents (risperidone or olanzapine) in the Medi-Cal program in the period immediately after removal of restrictions on the use of atypical antipsychotics. Our findings suggest that, compared with conventional treatment, the use of atypical therapies is associated with significantly less treatment switching and less use of concomitant anxiolytics and, especially, anticholinergics.

Treatment switching is clearly less of a concern than complete termination of antipsychotic therapy, which has been shown to increase relapse rates (

6,

7,

8,

9,

10). Nonetheless, the need to carefully titrate a new drug to control symptoms without leading to substantial adverse effects can complicate patient management. Along the same lines, the discontinuation of anticholinergics and anxiolytics may be viewed positively, because the prescribing of fewer medications reduces the chances of drug interactions and might be expected to lower the costs of care.

A few other studies have compared adherence to conventional versus atypical antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia outside of rigidly controlled clinical trial settings. In one recent analysis of data from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Dolder and colleagues (

18) reported modestly better adherence with atypical than with conventional antipsychotics. However, their summary measure—the compliant prescription fill rate—is not directly comparable to the measures we used.

Other studies that focused specifically on conventional antipsychotics confirm the poor adherence we observed. McCombs and colleagues (

12) found that only 12 percent of patients receiving these medications had a year of uninterrupted therapy, and the mean duration of therapy was 142 days, or 39 percent of days covered. More recently, Mojtabai and associates (

19) reported that more than 60 percent of first-admission patients with schizophrenia had gaps of 30 or more days in treatment in the period before the widespread use of atypical antipsychotics. The higher rate of adherence associated with the atypical antipsychotics in our study is consistent with the better tolerability profile for these medications that was reported in a recent meta-analysis of clinical trials (

14).

Some general limitations must be considered in interpreting data obtained from retrospective analyses of health care claims (

20,

21). First, the accuracy of diagnostic coding is variable and may be influenced by treatment guidelines, reimbursement, and other factors. In addition, prescriber selection bias may lead to a disproportionately higher number of patients with severe illness in one treatment group than in the other. Although we attempted to control for this potential bias by using multivariate analyses, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. It is reassuring that statistical adjustment confirmed and strengthened our conclusions about differences in adherence favoring the atypical antipsychotics. Second, patterns of medication use in this study were based on inferences of a correlation between filled prescriptions and medication taken by patients. However, the use of prescription drug claims in assessing medication adherence is well established (

22,

23,

24,

25,

26). Finally, this study was based on data for fewer than 300 patients from a single health insurance program. Because of geographic differences in treatment patterns, the varying socioeconomic status of patient populations, and differing coverage policies, caution should be exercised when generalizing our findings to other settings.

Conclusions

Compared with conventional therapies, the use of atypical antipsychotics was associated with significantly less therapy switching and a reduced use of concomitant medications. These factors may be important for therapeutic decision making.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in by Pfizer Outcomes Research. The authors thank Rick deFriesse, M.S., for his assistance with computer programming.