Physical assault against staff is an acknowledged occupational hazard in psychiatric inpatient settings (

1,

2) and may be a factor in the high turnover of staff in these settings. Violence toward staff in psychiatric hospitals, primarily on adult units, has received some scrutiny in the medical literature over the past three decades (

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16). However, the results of the studies are often difficult to interpret for a number of methodologic reasons. A variety of patient populations have been studied, and various definitions of the terms "violence" and "aggression" have been used (

1,

17).

Despite the prevalence of aggression in pediatric psychiatric hospitals, this phenomenon is underresearched. Pfeffer and associates (

18) studied an inpatient sample of 81 boys and 25 girls aged six to 12 years over a 45-month period between 1979 and 1982. Their study did not differentiate between verbal and physical aggression nor between aggression toward peers and aggression toward staff. A prospective study of individual assaultive events was not performed. The authors found that boys were more assaultive than girls and that assaultiveness was correlated with the diagnosis of conduct disorder.

Kelk and Cintio (

19) reported that patients who were likely to later be classified as violent could be identified on the basis of demographic information available at intake. Predictive variables were male gender and age of 12 to 15 years. Data were retrospectively compiled for day patients and inpatients whom the authors considered to have been violent toward staff and others over the course of two years (1982 to 1983). "Violent symptoms" included defiance, property destruction, stealing, running away, and aggression.

Kelsall and colleagues (

20) focused on adolescents who were hospitalized on a forensic inpatient unit in England. The definition of aggression included property destruction as well as aggression toward self and others. All 181 violent incidents recorded during a one-year period (1991 to 1992) were retrospectively analyzed in terms of severity, as measured on a 3-point scale derived from Fottrell (

21). The authors found that at least half the inpatient population was involved in some violent incident. Most of the incidents were minor, although 6 percent of the incidents resulted in "severity 3" injury (

20,

21). Adolescents who were admitted with a legal or forensic status were less frequently and less severely violent than those who were not.

We sought to expand on this sparse research base and examined 215 incidents that occurred in a single facility over a two-month period.

Methods

Participants and procedures

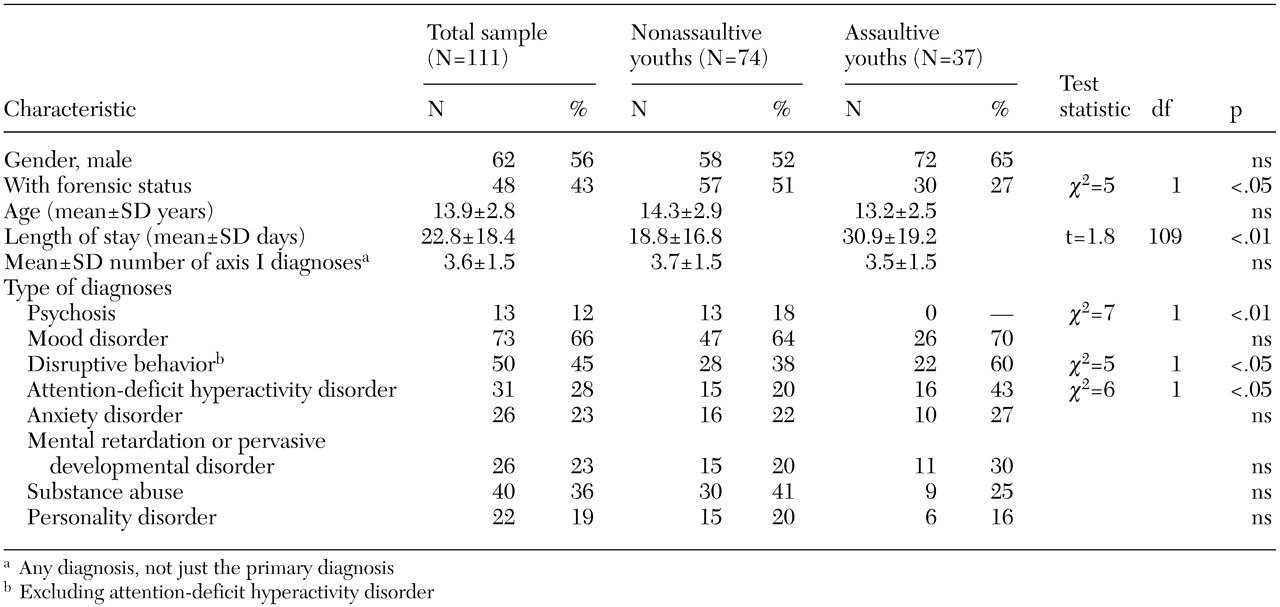

The study sample comprised all 111 patients who were hospitalized during the study period (December 3, 2001, to February 3, 2002) and all employees who had patient contact, including direct care staff, clinicians, and teachers (140 individuals) at a state-maintained inpatient psychiatric hospital for children and adolescents. Before the study was initiated, a protocol delineating the purpose and methods of the study was approved by the hospital's research committee.

Data were collected from all four hospital units, which housed up to 12 children per unit. The hospital census and mean length of stay during the study period did not differ significantly from average conditions over the fiscal year. During the study period, the average bed occupancy rate was 72 percent, and the mean length of stay was 22.8±18.4 days.

On admission, each patient was evaluated by a board-certified child psychiatrist. Within five days of admission, a staffing was scheduled, during which psychiatric diagnoses were amended on the basis of additional information and were agreed on by the patient's psychiatrist and psychologist. The diagnoses assigned at that meeting were the ones that were entered into our database.

For the purpose of data analysis, we collapsed axis I diagnoses into the following eight categories: disruptive behavior disorders (including conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), mood disorders (including major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, and mood disorders with psychotic features), psychotic disorders (including schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders), substance abuse, mental retardation and pervasive developmental disorders (including autism and Asperger's syndrome), anxiety disorders, and personality pathology (including personality disorder traits that were specifically noted on axis II).

Data collection

All staff who were involved in the direct care of patients were asked to participate in the study and, if they had been assaulted, to complete a confidential questionnaire immediately after the assault. The questionnaire was designed by the authors and is available on request. Staff had the option of identifying themselves by name or remaining anonymous.

Physical aggression or assault was defined as pushing or striking a staff member with or without a weapon; throwing an object at a staff member, including spitting; or sexual touching of a staff member. Verbal threats or aggression, self-injury, and property destruction were not included.

Survey instrument

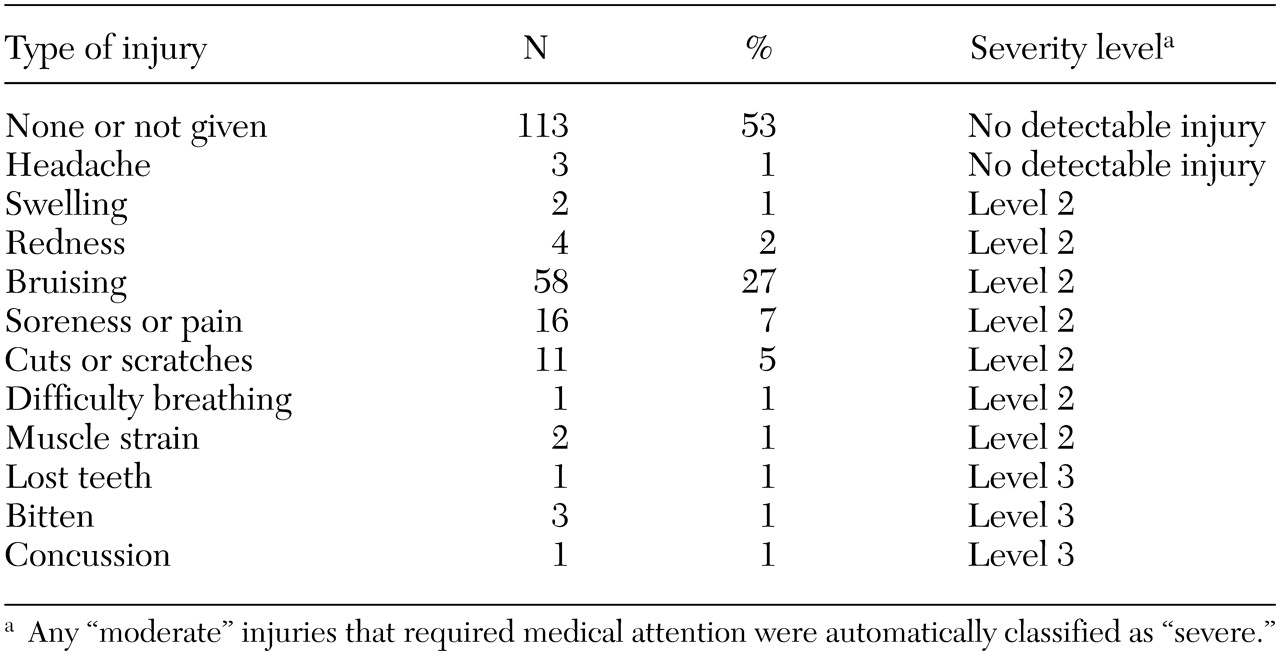

The questionnaire elicited specific information about the assault (such as type, location, time, severity, antecedents or precipitants, and relationship to physical contact or restraint), the patient's name, the nature and severity of any injuries, and the victim's gender and number of years of employment at the hospital. The severity of patients' assault of staff was rated (by EPR and MB) on a 3-point scale derived from Fottrell (

21): level 1, acts that did not result in any detectable physical injury; level 2, acts that resulted in minor injury (such as a scrape, a minor laceration, or a bruise); level 3, acts that resulted in major physical injury (such as a fracture, a large laceration, or an injury that required medical intervention).

Discussion and conclusions

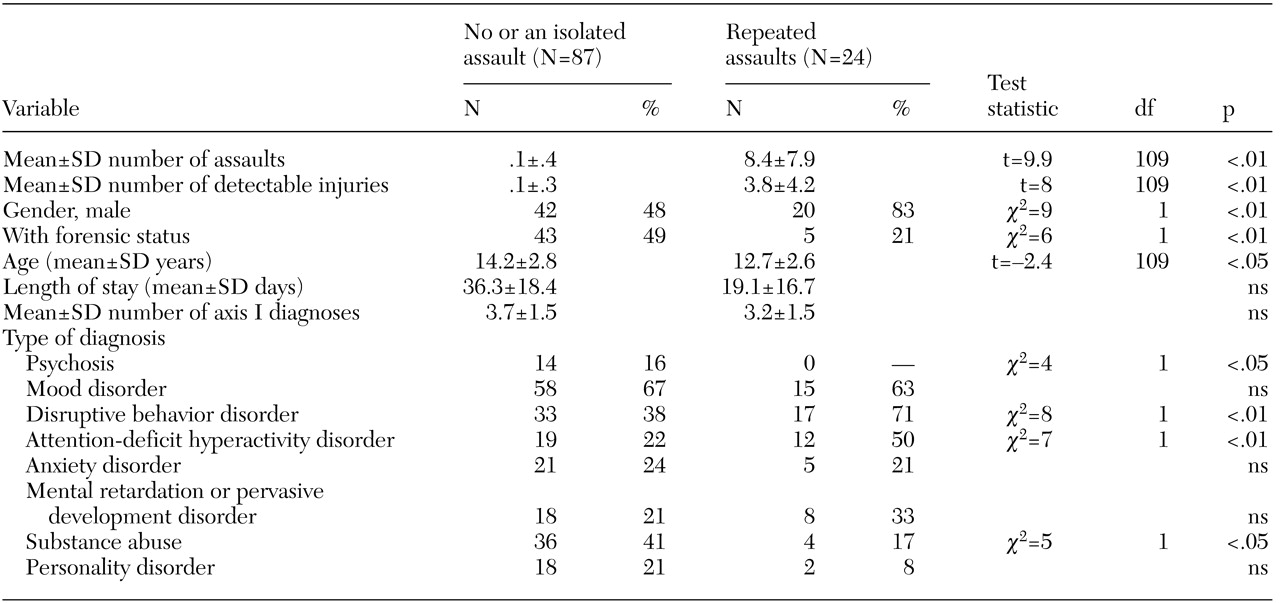

The results of this study indicate that physical assault against staff in child and adolescent psychiatric settings is frequent and problematic. One-third of the patients who were hospitalized over a 60-day period assaulted staff. A total of 215 incidents of assault occurred over the study period, representing an average of 107.5 assaults a month. We did not anticipate such a high frequency of assault. During the six months before the study, 83 staff assaults were reported, for an average of 13.8 a month. During the six months after the study, 105 staff assaults were reported, for an average of 17.5 a month.

The formal mechanism for reporting assaults in the hospital is through incident reports, shift reports, and seclusion and restraint logs. Reliance on formal incident reports as indicators of assaults of staff has been noted to underrepresent the frequency of assault (

1,

22,

23)—reporting increases with the severity of the assault (

24).

The inverse relationship we found between assaults and forensic status has been noted before (

20). It is our experience that although more pediatric psychiatric patients are currently admitted with forensic status than was the case a decade ago, these patients are no more violent or dangerous than are other hospitalized youths. The factors involved in a child or adolescent's receiving mental health treatment rather than a more punitive juvenile justice intervention may have little to do with the severity of psychopathology. We propose that staff employed in psychiatric facilities may be in as much or greater danger of assault than staff in correctional facilities.

Well-designed prospective studies of assault of staff working in juvenile correctional facilities are clearly indicated. It is possible that staff in hospitals such as the one in this study—hospitals that treat children and adolescents with more acute illness who have not responded rapidly to inpatient interventions—are more vulnerable to assault. The Commonwealth of Virginia's entry-level pay range for staff at juvenile correctional facilities is higher than that for entry-level staff at state psychiatric hospitals, presumably because of the assumed greater risks inherent in working closely with an incarcerated delinquent population. The results of our study indicate that this assumption may need to be reexamined.

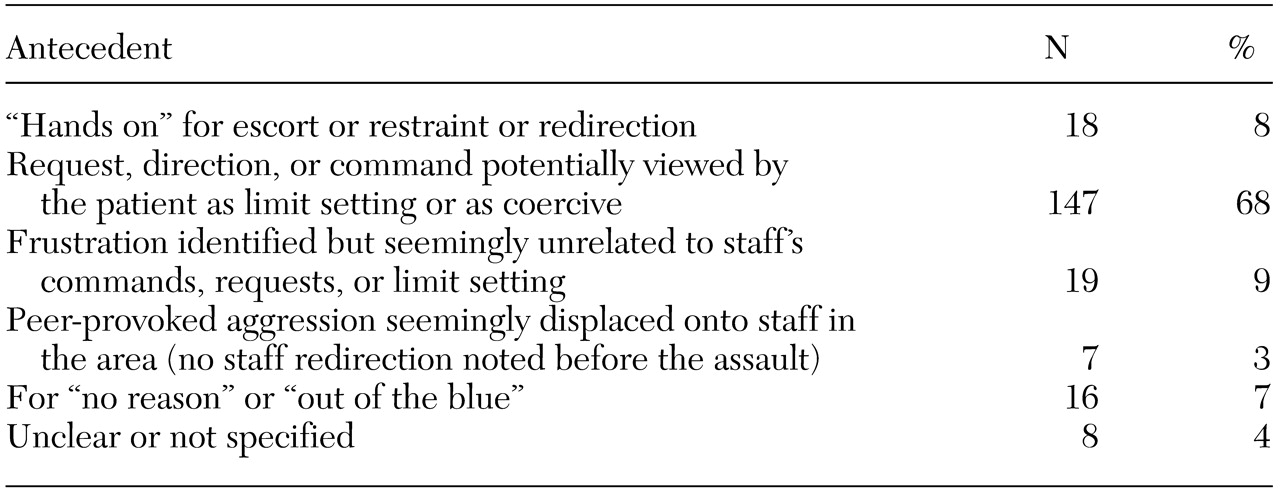

The frequency of directive verbal interactions (typically minor) as antecedents of assault was unexpected. Our hypothesis was that staff's laying hands on patients in an effort to physically control or redirect them did not precipitate most assaults, and this hypothesis was validated by our findings. However, 68 percent of the assaults were preceded by a verbal direction or redirection or limit setting on the part of the staff. The center uses a level-based behavioral management program that varies from unit to unit, depending on the developmental level of the patient population. However, the presence of rules and the awarding of "points" and reinforcers and privileges according to the patient's level in the program are consistent across units. Staff members are given the tasks of setting limits as outlined in the unit behavioral programs and of reminding patients when they are not complying with expectations. The results of this study raise questions about the link between rules, limit setting, and staff assault. At the outset of their employment (and in periodic refresher courses), all staff receive training that emphasizes verbal deescalation in staff-patient interactions. All staff and clinicians who had patient contact were trained in the Mandt system, which emphasizes deescalation techniques independent of physical management (

25). However, it is possible that the very nature of limit setting may place staff at risk of assault.

The only association we observed between assault and gender was that noted for repeat assaulters. Girls were as likely as boys to assault a staff member at least once and to seriously injure staff. However, boys were more likely than girls to be repeat assaulters. The finding of an overall similar prevalence of assaultive behavior for males and females with mental disorders has been noted by other investigators (

2,

9,

26).

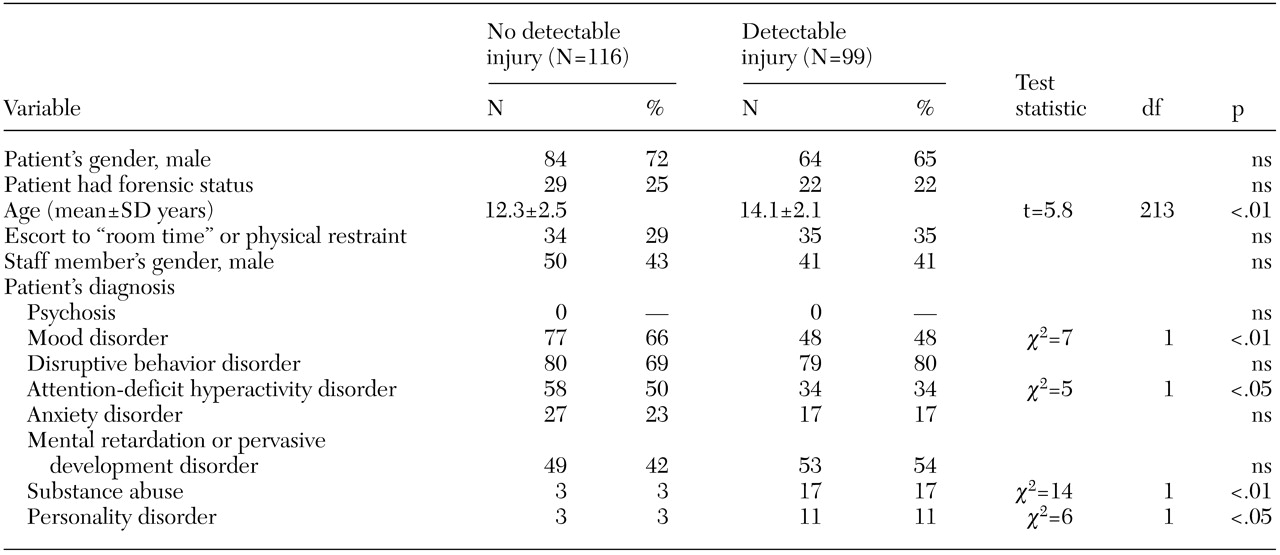

The positive relationship between assault status and the diagnosis of a disruptive behavior disorder, ADHD, and longer hospital stay was expected. Almost all the children and adolescents who were hospitalized at the center had axis I diagnoses other than or in addition to a disruptive behavior disorder. The presence of a comorbid disorder—and especially the additive effect of irritability and impulsivity that a mood disorder and disruptive behavior disorder or ADHD confer—would be expected to result in elevated aggression in this population. The negative association between repeat assaulter status and substance abuse was unexpected. However, a limitation of this study is that we were unable to analyze specific types of substance abuse, which could clarify this finding. For example, alcohol, cocaine, or inhalant abuse might be expected to have a stronger link to violence than cannabis abuse. Also, younger children (who were assaultive and included in the sample) would be less likely to present with substance use that met criteria for substance abuse.

Although assaultiveness was not linked to the presence of a neurologic disorder or significant neurologic findings in this study, youths with disruptive behavior disorders—specifically ADHD—are prone to negative misattribution and are impulsive.

Because this study had no exclusion criteria and all patients and staff who were assaulted were included in the analysis, the sample reflects a heterogeneous group of psychiatrically hospitalized children and adolescents. Thus in many respects our findings are generalizable to other inpatient child and adolescent facilities. However, the hospital's lack of direct dependence on revenues from insurance and Medicaid probably selects for patients who are sicker and poorer than those who are rapidly evaluated, stabilized, and discharged from private hospitals.

There is an obvious need for detailed data collection if further gains in the development of profiles of various types of patient-staff interactions and of characteristics of assaultive psychiatric inpatients are to be made. More thoughtful and individualized proactive treatment of assaultive and potentially assaultive patients is also necessary for the retention of high-quality staff to work with these patients—staff who can maintain therapeutic interactions so that effective inpatient stabilization and treatment as well as transition to community settings can be achieved.