Information was obtained through repeated searches in MEDLINE, PsycLIT, PubMed, and the Web of Science for articles published since the 1990s, using the terms "substance abuse-addiction-substance use disorders," "case management," and "development-implementation."

Key questions

Which problems are addressed with case management, and what are its objectives and target group? The observation that many persons with substance use disorders have significant problems in addition to abusing substances has been the main impetus for using case management as an enhancement and supplement to substance abuse treatment (

27,

28,

29,

30,

31). In the United States, the paucity and selective accessibility of available services, shortcomings in the overall quality of service delivery (accountability, continuity, comprehensiveness, coordination, effectiveness, and efficiency), and cost containment were further incentives for implementing case management (

14,

18,

19,

32). The implementation of case management in the Netherlands was not driven merely by economic concerns but rather by the poor quality of life of many chronic addicts and the nuisance they cause in city centers (

31). In Belgium, the chronic and complex problems of many substance abusers and the lack of coordination and continuity of care were the main reasons for introducing case management (

30).

Unlike in the United States, case management has not been applied as widely among substance abusers in Europe because of better availability and accessibility of services, less stress on cost containment, and conflicting outcomes about the effectiveness of case management for persons with mental illness, among other reasons. However, recent reforms in substance abuse treatment—for example, in the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium—have shifted the focus toward accessibility, continuity, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency and stimulated interest in case management (

15,

33,

34). Since 1995, more than 50 projects have been developed in the Netherlands that make use of case management, whereas the number of case management projects for this population in Belgium is limited to five to ten (

30,

31).

In the United States, case management has been implemented successfully for enhancing treatment participation and retention among substance abusers in general (

35,

36,

37,

38) and for populations with multiple needs that experience specific barriers in obtaining or keeping in touch with services, such as pregnant women, mothers, adolescents, persons who are chronically publicly inebriated, persons with dual diagnoses, and persons with HIV infection (

11,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44). Most of these programs intend to promote abstinence, whereas case management programs in Europe apply a harm-reduction perspective. In the Netherlands, the implementation of case management has been directed mainly at severely addicted persons, such as street prostitutes, mothers of young children, homeless persons, and persons with dual diagnoses, who are often served inadequately or not at all by existing services. According to program providers, case management has contributed substantially to the stabilization of these persons' situation (

45). In Belgium, case management has mainly been reserved for substance abusers with multiple and chronic problems, resulting in improved drug-related outcomes and better coordination of the delivery of services (

46).

Target populations may also include persons with substance use disorders who are involved in the criminal justice system, and these interventions have been associated with reduced drug use and recidivism and with increased service use (

47,

48,

49). However, uncertainty remains about the differential effect of coercion in case management (

50,

51). This intervention has further been used to address "the most problematic clients," an approach that has been associated with adverse outcomes in the field of mental health care (

6), but various studies among substance abusers have shown cost-effectiveness and beneficial outcomes (

16,

40,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56). Nevertheless, several authors have reported practical problems—for example, the difficulty of long-term planning, increased risk of burnout among case managers, and clients' becoming totally dependent on their case manager (

21,

46,

53,

57).

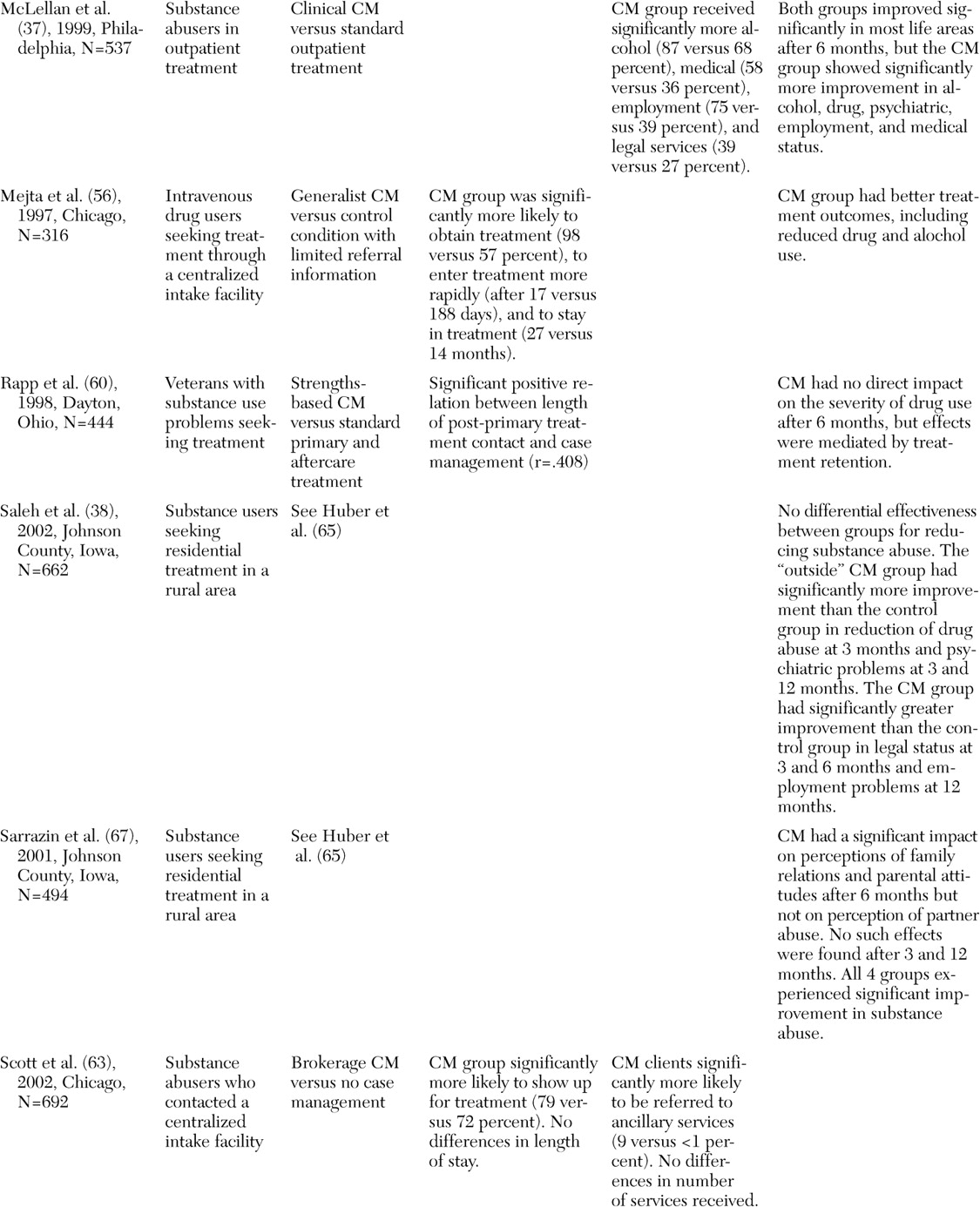

An overview of recently published (1997 to 2003) peer-reviewed studies of case management that have included at least 100 substance abusers revealed that case management has been relatively successful for achieving several of the postulated goals in the United States, whereas similar outcome studies are still forthcoming in Europe (

Table 1). Several controlled studies have shown significant improvements in treatment access, participation, and retention or service use among clients who have received case management services (

36,

37,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65), whereas evidence on the effects on drug-related outcomes is still conflicting. Generally, small to moderate improvements have been demonstrated among clients who received case management services (

58,

62,

64,

66,

67), but these effects sometimes tended to decline over time (after nine to 12 months) (

38,

59) or did not differ significantly from those of similar control interventions, such as behavioral skills training and other models of case management (

25,

44,

60). Finally, various uncontrolled studies have shown significantly improved outcomes compared with baseline assessments (

34,

35,

46,

68). However, in the absence of a control condition, such effects may have wrongly been attributed to case management.

What is the position of case management in the system of services, and how can cooperation and coordination between services be enhanced? Several authors have argued that the success of case management depends largely on its integration within a comprehensive network of services (

8,

21,

69,

70,

71). Case management risks being just one more fragmented piece of the system of services if it is not exquisitely sensitive to potential system-related barriers, such as waiting lists, inconsistent diagnoses, opposing views, and lack of housing and transportation (

72).

McLellan and colleagues (

37) found no effects of case management 12 months after implementation but did find effects after 26 months. They concluded that there was a strong influence of various system variables—for example, program fidelity and availability and accessibility of services—and recommended extensive training and supervision to foster collaboration and precontracting of services to ascertain their availability. Access to treatment can be markedly improved when case managers have funds with which to pay for treatment (

58). In addition, formal agreements and protocols are needed concerning the tasks, responsibilities, and authorities of case managers and other service providers involved; the use of common assessment and planning tools; and exchange and management of client information (

13,

14,

21,

57,

73).

Case management can be implemented as a modality provided by or attached to a specific organization, such as a hospital or a detoxification center, or as a specific service jointly organized by several providers to link clients to these and other services. The former program structure has been widely applied in the United States for enhancing participation and retention and reducing relapse, whereas the latter is frequently used in Belgium and the Netherlands to address populations at risk of falling through the cracks of the system.

Vaughan-Sarrazin and colleagues (

61) studied the differential impact of programs' locations and compared the effectiveness of three types of case management with a control condition. The variant that involved case managers housed inside the facility was associated with significantly greater service use compared with the other conditions, which suggests that the accessibility and availability of case management programs mediate the success of these programs.

What model of case management should be used, and which are crucial aspects of effective case management? Although most practical examples only vaguely resemble the pure version of a case management model, four models of case management are usually distinguished for working with substance use disorders: the brokerage-generalist model, assertive community treatment-intensive case management, the strengths-based model, and clinical case management (

14,

19). Model selection should be dictated by what services are already available, the objectives and target population, and any available empirical evidence.

Assertive community treatment, and especially intensive case management, with its focus on a comprehensive (team) approach and the provision of assertive outreach and direct counseling services, has been used in the United States for reintegrating incarcerated offenders, among other populations (

24,

47,

49). A randomized study of 135 parolees, half of whom received case management services, showed little differential effect on drug use, but some improvement was found in relation to risk behavior and recidivism (

24).

Random assignment to intensive case management compared with two other interventions was associated with a decline in drug use and criminal involvement and an increase in treatment participation among almost 1,400 arrestees (

49). In addition, intensive case management has been applied successfully in other populations with complex and severe problems—for example, homeless persons and persons with dual diagnoses (

40,

42,

52,

53,

66,

68). Intensive case management is the predominant model in Belgium and the Netherlands and has been associated with the delivery of more comprehensive and individualized services and improved outcomes (

31,

46).

Two large studies in Dayton, Ohio, and in Iowa, sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, have applied strengths-based case management among persons with substance abuse who are entering initial treatment (

Table 1). The Ohio study found evidence for improved employment functioning and enhanced treatment retention, which, in turn, was associated with a positive effect on outcomes concerning drug use and criminal involvement (

36,

60,

64,

74,

75). According to clients, retention was promoted by the client-driven nature of goal setting and was facilitated by case managers' assistance in teaching clients how to set goals (

76). The Iowa study showed an impact of case management on the use of medical and substance abuse services and moderate, but fading, effects on legal, employment, family, and psychiatric problems (

32,

38,

61,

65,

67).

Brokerage models and other brief approaches to case management have usually not demonstrated any discernable benefits of case management compared with control groups who did not receive case management services (

77,

78). However, recent studies have shown a positive impact of case management on service use and access to treatment (

66) and equal effectiveness compared with intensive case management (

44). Generalist or standard case management has been associated with significant positive effects on treatment participation and retention and relapse (

35,

58). Clinical case management, which combines resource acquisition and clinical activities, has rarely been applied among persons with substance use disorders but was successful in at least one study (

37). Other authors have stated that combining the role of counselor and case manager is problematic, because it dilutes both aspects of the program (

24).

In summary, as opposed to case management for persons with mental illness (

3,

6,

79,

80), little information is available about crucial features of distinct models and their effectiveness for specific substance abusing populations.

Which qualifications and skills should case managers have, and what types of support should be provided? Several authors assume that previous work experience, extensive training, knowledge about the health care and social welfare systems, and communication and interpersonal skills are at least as important as formal qualifications (

14,

31,

34). Only some programs have involved people who have recovered from addictions as case managers (

81), but no information is available about the differential impact of case management by professionals or peers. The client-case manager relationship has been identified as crucial for promoting case management participation and related outcomes, and the application of a strengths-based approach can stimulate clients' involvement (

34,

46,

74,

76).

Analyses of case management activities and program fidelity have shown large variations among case managers, not only within but also across programs (

13,

14,

25,

35,

44,

68). Poor program fidelity and nonrobust implementation of case management have been associated with worse outcomes, but fidelity and implementation can be optimized by extensive initial training, regular supervision, administrative support, application of protocols and manuals, treatment planning, and a team approach (

13,

25,

37).

Variety across programs has resulted in attempts to standardize and guide case management in the United States. The National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors identified case management as one of eight counseling skills (

82), and the commonly cited case management functions have been incorporated into the referral and service coordination practice dimensions of the addiction counseling competencies (

83). In the Netherlands, a Delphi study was organized to reach a broad consensus on the core features of case management, resulting in a manual that will serve as a touchstone for the future development, implementation, and evaluation of case management (

31,

84). The Delphi method comprises a series of questionnaires sent to a preselected group of experts—for example, clients, case managers, and program directors—who respond to the problems posed individually and who are able to refine their views as the group's work progresses (

85). It is believed that the group will converge toward the best response through this consensus process, based on structuring of the information flow and feedback to the participants.

Case managers' caseloads vary but usually do not exceed 15 to 20 clients for a case manager who is providing intensive contacts to substance abusers who have multiple and complex problems (

13,

21,

34,

41,

52). A team approach helps to deal with large and difficult caseloads but also to extend availability and guarantee case managers' safety (

34,

86). Most researchers have found little effect of the intensity of mental health case management (

6,

35,

44), whereas others have related high "dosages" of case management with either improved or adverse outcomes (

34,

68).

How should case management projects best be financed, and how can their continuity be guaranteed? The burgeoning interest in managed care financing structures resulted in an explosive growth of case management initiatives in the United States during the 1990s (

32). Most programs have been set up as experiments, but, despite positive results, only some have been integrated into the service system on a long-term basis. On the other hand, case management programs in the Netherlands became part of the system of services shortly after implementation and without many indications of effectiveness (

31). Both observations illustrate that continued funding might be predicted on the basis of issues that have little to do with success or failure of the intervention itself.

Developing projects should be given sufficient time—three to five years—to realize their objectives, given that it has been shown that it may take up to two years before case management generates the intended outcomes (

37). Alternative or flexible forms of reimbursement need to be negotiated with insurance companies, because case managers' activities often represent departures from traditional interventions in substance abuse treatment (

87). In addition, a budget for occasional client expenses—for example, child care, clothing, and public transportation—can facilitate case management (

37,

43,

57). Ultimately, continued funding should be based on a thorough evaluation of the program's postulated goals.

Which standards should be used to evaluate case management? Effectiveness needs to be evaluated according to scientific standards, but requirements from commissioning and subsidizing authorities should also be taken into account (

14). Evaluation should start from an accurate representation of what the intervention entails (

23). Without this knowledge, it is only possible to vaguely search for outcomes that might be more or less attributable to case management. Besides outcome indicators, process data should be collected that describe the degree to which the planned intervention is actually delivered, the impact of other factors on the intervention, and the specific outcomes that can be attributed to case management (

14,

47).

Researchers have identified several potential confounding factors—for example, individual case managers' personalities, client characteristics, motivation, legal status, and treatment participation and retention—that affect the direct impact of case management on clients' functioning (

25,

36,

52,

68,

60,

64,

88,

89). Contextual differences cause further methodologic problems in the evaluation of case management. To extend current knowledge about the effectiveness of case management for persons with substance use disorders, more randomized controlled studies with large samples are needed, especially in Europe. Also, a longitudinal scope and qualitative research that focuses on specific aspects of case management and the role of mediating variables could provide further insights into the factors that make case management work.

Conclusions

In both the United States and Europe, case management is regarded as an important supplement to traditional substance abuse services, as it provides an innovative approach—client centered, comprehensive, and community based—and contributes to improved access, participation, retention, service use, and client outcomes. Compared with case management for persons with mental illness, case management for persons with substance use disorders has fairly little evidence available of effectiveness.

Contextual differences, specific target populations, diverging objectives, less tradition of community care, few randomized and controlled trials, and unrealistic expectations about the effectiveness of case management in this population may account for this lack of evidence. Especially in Europe, more randomized controlled trials that include sufficiently large samples are needed, as well as qualitative studies, in order to better understand distinct aspects of case management and their impact on client outcomes and system variables.

Case management for substance use disorders is no panacea, but it positively affects the delivery of services and can help to stabilize or improve an individual's complex situation. On the basis of empirical findings from the United States, the Netherlands, and Belgium, several prerequisites for a well-conceptualized implementation of this intervention can be mentioned. Integration of the program in a comprehensive network of services, accessibility and availability, provision of direct services, use of a team approach, application of a strengths-based perspective, intensive training, and regular supervision all contribute to successful implementation and, consequently, to beneficial outcomes.

Still, the variety of case management practices within and across programs remains a major concern. Development of program protocols and manuals and the identification of key features of distinct models can contribute to a more consistent application of this intervention.

Finally, although case management for persons with substance use disorders has evolved somewhat independently, many similarities can be observed with mental health case management. Therefore, further evolutions in this sector should be closely followed, especially for identifying the crucial features of case management. Moreover, a comparison of case management for both populations may reveal unique aspects of each intervention that allow optimization of case management practices among patients with mental illness, persons with substance use disorders, and persons with dual diagnoses.