Between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2002, a total of 44,851 patients visited Parkland's psychiatric emergency service, generating 75,815 separate visits. Among these patients, 11,669 (26.02 percent) made at least one return visit within 26 weeks of a previous visit, accounting for 30,964 (40.8 percent) of the 75,815 visits. The interval between the index and the first return visit ranged from one day to 2,882 days. Of all study-defined repeat visits, 13.7 percent, 20.8 percent, 30.5 percent, and 63.0 percent were made within 1, 4, 8, and 26 weeks, respectively.

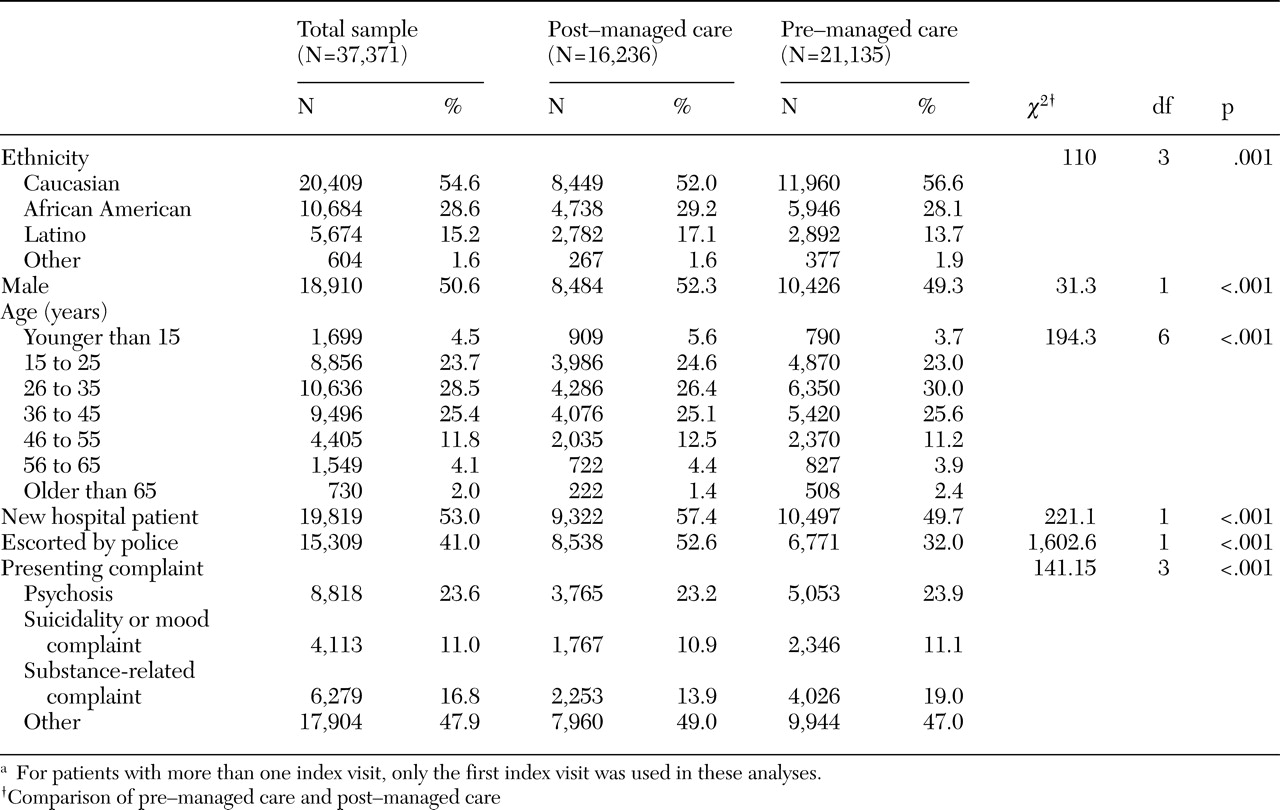

Using study-defined criteria for an index visit and requiring information on age to be present, we created a final analytic sample of 37,371 patients (83.3 percent of all patients): 21,135 in the pre-managed care group and 16,236 in the post-managed care group. Among the 37,371 patients, 2,271 (6 percent) made a return visit within one week, 3,106 (8 percent) within two weeks, 4,170 (11 percent) within four weeks, 5,162 (14 percent) within eight weeks, and 6,851 (18 percent) within 26 weeks. Compared with the excluded sample, the final analytic sample had more whites (20,409 whites, or 54.6 percent, compared with 3,940 whites, or 52.7 percent) and fewer African Americans (10,684 African Americans, or 28.6 percent, compared with 2,340 African Americans, or 31.3 percent) and Latinos (5,674 Latinos, or 15.2 percent, compared with 1,100 Latinos, or 14.7 percent) (χ

2=24.91, df=3, p<.001). As shown in

Table 1, rates of presentation for care by presenting complaint remained relatively stable across the two cohorts. However, visits for which the presenting complaint was the treatment of substance-related problems declined after NorthSTAR was implemented, and presentations in the "other" category increased by 4.1 percent.

Demographic and index visit characteristics

Gender and ethnicity. At the time of the index visit, males were slightly more likely than females to be new hospital patients (51.4 percent of males compared with 46.7 percent of females; χ2=85.14, df=1, p<.001, Yates continuity correction) and to be escorted by police (44.8 percent of males compared with 38.0 percent of females; χ2=194.99, df=1, p<.001). When the analyses were adjusted for age, ethnicity, and characteristics of the index visit (whether there was a police escort, whether the patient was new to the hospital, and whether managed care had been implemented), males were 37.7 percent more likely than females to have a return visit to the emergency department (odds ratio [OR]=1.38, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.33 to 1.42, p<.001). Male patients were more likely to revisit than female patients, both before managed care (OR=1.34, CI=1.29 to 1.41, p<.001) and after managed care (OR=1.41, CI=1.34 to 1.48, p<.001), and there was a 4.9 percent increase in the risk that males would enter psychiatric emergency services after managed care was implemented, although this result was nonsignificant.

African Americans were substantially less likely than the other ethnic groups, including Latinos, to present at the index visit as first-time hospital patients (29.0 percent of African Americans, compared with 57.4 percent of persons from other ethnic groups; χ2=2,691.57, df=1, p<.001). African Americans were not more likely than the other ethnic groups to be escorted by the police at the index presentation. After the analysis was adjusted for age, gender, and characteristics of the index visit, African Americans were more likely than whites to revisit the emergency department (OR=1.22, CI=1.17 to 1.27, p<.001). The risk of having a return visit did not vary significantly between African Americans and whites, either before or after managed care was implemented.

Latinos were slightly more likely than other ethnic groups to have their index visit be a first hospital encounter (55.7 percent of Latinos compared with 47.8 of persons from another ethnic group; χ2=120.48, df=1, p<.001). In addition, Latinos were somewhat less likely than other ethnic groups to present involuntarily for their index visit. After the analyses were adjusted for age, gender, and characteristics of the index visit, Latinos were not as likely as whites to have a return visit (OR=.79, CI=.75 to .83, p<.001). Following the implementation of managed care, revisit rates among Latinos increased compared with those of whites (pre-managed care, OR=.73, CI=.67 to .78, p<.001; post-managed care, OR=.85, CI=.80 to .92, p<.001; difference between pre- and post-managed care, OR=1.18, CI=1.06 to 1.31, p=.003).

In summary, males were 1.38 times as likely as females and African Americans were 1.22 times as likely as whites to have a repeat visit; the implementation of managed care did not produce a statistically significant difference in these risk factors. In contrast, before managed care was implemented, Latinos were only .78 times as likely as whites to have a return visit—a rate that increased to .85 after managed care was implemented. That is, managed care appears to have left unaffected the higher return rates found among African Americans and males, although it was associated with increased return rates among Latinos. Even so, after managed care was implemented, Latinos continued to have lower rates of return visits than whites.

Age. The association between age and return visits can be described as an inverted "U" shape, in which middle-aged patients (aged from 36 to 55 years) had the highest return rates, and very young and very old patients had the lowest rates. Specifically, children younger than 15 years and adults older than 65 years were less likely than middle-aged patients to return as patients (children younger than 15 years, OR=.78, CI=.72 to .85, p<.001; adults older than 65 years, OR=.78, CI=.69 to .87, p<.001). The effect size was smaller for young adults aged 15 to 25 years. Compared with their middle-aged counterparts, young adults aged 15 to 25 years were not as likely to make a repeat visit (OR=.95, CI=.905 to .989, t=2.43, p=.015).

Police escorts and first-time hospital visitors. As shown in

Table 1, the proportion of patients accompanied by police on their first index visit increased significantly across the two periods (32.0 percent before managed care was implemented compared with 52.6 percent after managed care). However, these involuntary patients did not revisit the emergency department as often as voluntary patients. After the analyses were adjusted for other patient characteristics, patients who were escorted by the police to their index visit were not as likely to return as patients who presented voluntarily to their index visit (OR=.87, CI=.84 to .90, p<.001). By far, the most important predictor of return rates was whether the patient had previously used hospital services. Specifically, first-time users in both cohorts were not as likely to revisit as previous hospital patients (OR=.68, CI=.65 to .70, p<.001).

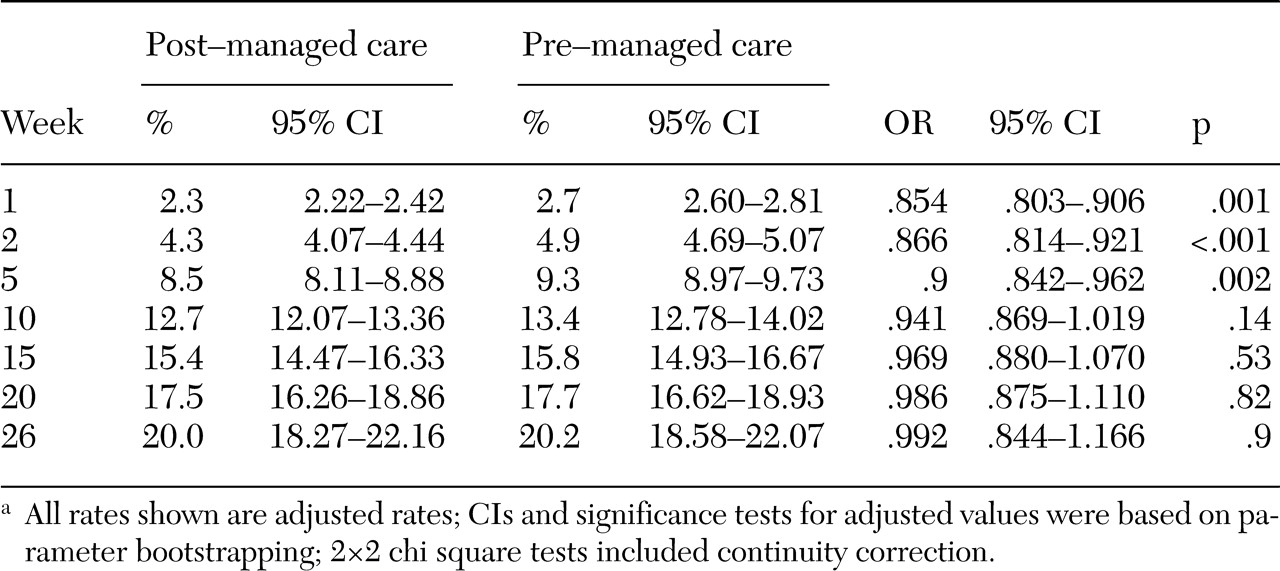

Return rates over time. When adjusted cumulative probabilities were tabulated, the referent patient had an adjusted first-week revisit rate of 2.70 percent before managed care was implemented (crude, unadjusted rate of 3.60 percent). After managed care was implemented, the referent patient had an adjusted first-week revisit rate of 2.32 percent (crude, unadjusted rate of 2.97 percent).

Weekly return rates (p

t/[p

t+1]) declined over time. The rate of initial decline before managed care was implemented was 81.8 percent of the rate of the previous week (exp[β

10=.82, CI=.81 to .82, t=44.20, df=37,362, p<.001), while the rate of initial decline after managed care was implemented was 84.9 percent. Declining-effects analyses were also used to compare differences between pre- and post-managed care for patients with characteristics similar to those of the average patient in the referent population. We found that patients during post-managed care were 85 percent less likely to have a return visit than their pre-managed care counterparts (exp[β

01]=.854, CI=.80 to .91, t=5.15, df=37,362, p<.001). (Note that the trivial difference in the 95 percent CI described in

Table 2 is based on a parameter bootstrap, and the CI reported here is based on an exact estimate of the robust standard error taken from the covariance matrix of the estimated declining-effects model.) However, the post-managed care advantage did not appear to last over time, as post-managed care rates after a patient's index visit tended initially to increase by 1.04 percent per week more than the rates in the pre-managed care group: (exp[β

11]=1.038, CI=1.02 to 1.05, t=5.63, df=37,362, p<.001), although this rate decelerated over time to only 99.87 percent of its preceding time rate (exp[β

12]=.999, CI=.998 to .999, t=4.80, df=37,362, p<.001). Expressed another way, average time for managed care effects to expire following an index visit was 5.17 weeks (CI=2.537 to 9.148). This estimate was computed by solving the quadratic equation for time for the coefficients of the time and managed care interaction terms.

In short, post-managed care patients were only 85.3 percent as likely as their pre-managed care counterparts have had a return visit during the first week after an index emergency department visit (t=5.15, p<.001). However, this advantage seen in the post-managed care group did not extend to subsequent weeks after the patients' index visit. By 5.17 weeks after the index visit, the likelihood that a patient would return to the psychiatric emergency service for additional care was essentially the same before and after managed care (CI=2.54 to 9.15, p<.001).

As shown in

Table 2, adjusted rates were computed for selected weeks after the index visit: weeks 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 26. (CIs and significance tests were determined on the basis of bootstrapping the parameters 20,000 times.) Although some effects of managed care on revisit rates were observed during the first ten weeks after the index visit, there were no observable effects of managed care after that point. In fact, differences in the likelihood of return visits occurred largely during weeks one through five after the index visit. At the end of 26 weeks, there were no differences between the pre- and post-managed care periods in the overall probability that the patient would have revisited the psychiatric emergency service. This finding suggests that this managed care system may merely delay, rather than prevent, return visits to the psychiatric emergency service.