Second-generation antipsychotics are generally considered to be as effective as first-generation agents for the treatment of psychotic disorders but have a lower propensity to cause side effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. These newer medications may also be more effective for treating negative and cognitive symptoms associated with psychotic disorders (

1). Second-generation agents are now considered first-line treatment for psychotic disorders and, in some cases, are approved for treatment of mania and prevention of suicide (

2).

Second-generation antipsychotics may be especially useful in managing psychotic symptoms among elderly patients, who are particularly sensitive to side effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, sedation, and orthostatic hypotension and often suffer injuries, such as falls, while taking psychotropic medications (

3).

In general, second-generation antipsychotics are associated with fewer movement disorders than traditional antipsychotics, and certain second-generation antipsychotics may also cause less sedation and have fewer cholinergic effects than traditional medications. Indeed, since the introduction of risperidone to the U.S. market in 1990, second-generation antipsychotics have become common in managing psychotic symptoms that are often associated with Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia (

4).

There is emerging evidence of sociodemographic disparities in the use of these medications. For example, African-American patients with schizophrenia are less likely to receive a second-generation antipsychotic. Older age has also been associated with decreased propensity to receive second-generation antipsychotics. However, we were unable to find reports of whether racial disparities exist within a population of older persons. In the study reported here we used Medicaid paid claims to explore potential racial disparities in the use of antipsychotics among elderly residents of nursing homes.

Methods

This study was a retrospective pharmacoepidemiologic study of antipsychotic use among elderly Medicaid recipients residing in nursing homes. This project was conducted as part of a contract between the Arkansas Medicaid program and the department of psychiatry of the College of Medicine at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. The contract targeted nursing home residents who were receiving antipsychotics. Project staff provided psychiatric consultation to the provider who was caring for the patients. The data reported here evaluate only the Medicaid paid claims that were used to identify patients for the larger project. This study was conducted in accordance with the policies of the university's institutional review board.

Using Medicaid pharmacy claims, we identified residents who lived in a nursing home, had at least one paid claim for an antipsychotic medication, and were older than 65 years between January and October of 2001. Demographic data, also obtained from Medicaid files, included age, gender, and race and location of the nursing home.

Antipsychotic prescription data included the name and strength of the medication, the amount dispensed, the number of days' supply, and the date dispensed. Second-generation antipsychotics were defined as risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and clozapine. Prescriptions for short-acting injectable antipsychotics were excluded. The index prescription for inclusion in the analysis was defined as the last antipsychotic prescription during the evaluation period.

Nursing home residents were drawn from 215 facilities. The mean±SD number of residents selected from any one nursing home was 12.7±7.0 (range, 1 to 36). Given the small number of participants per nursing home, we could not control for clustering. However, by controlling for nursing home location we could control for potential differences in the availability of mental health care throughout the state. The location of the nursing home was coded as one of five health management areas as defined by the Arkansas Department of Health: northeast, northwest, central, southeast, and southwest. The central health maintenance area is the most populous area in the state and includes the medical school and the largest number of mental health professionals. This health maintenance area was used as the referent group with which to compare the other health maintenance areas because we believed that prescribers in this area would be the most likely to use and understand the newer antipsychotics.

Chi square and t tests were used to compare the relationship between receipt of a second-generation antipsychotic and race, gender, and age. A logistic regression model was used to examine the relationship between residents' race and likelihood of receiving a second-generation antipsychotic. The dependent variable (likelihood of receiving a second-generation antipsychotic) was modeled as a dichotomous variable (yes or no). The independent variables included in the model were age, race, gender, and location of the nursing home. Age was included as a continuous variable. Race and gender were included as dichotomous variables (African American or Caucasian and male or female, respectively). Location was based on one of five health maintenance areas as described previously. In light of the multiple comparisons, significance was set at p<.01.

Results

Of the 21,321 residents of nursing homes in Arkansas during the study period, 2,717 (12.7 percent) met the study's inclusion criteria. Of the residents included in the analysis, 2,017 (74.2 percent) were women, and most were Caucasian (2,222 residents, or 81.8 percent); the racial breakdown of the non-Caucasian participants was 419 African Americans (15 percent), one Native American (<1 percent), two Hispanics (<1 percent), two Asians (<1 percent), four of other racial backgrounds (<1 percent), and 76 of unknown race (2.8 percent). The mean age of the participants was 82.4±8.3 years (range, 65 to 103). The most common antipsychotic prescriptions were risperidone (1,304 residents, or 48 percent), olanzapine (589 residents, or 21.7 percent), haloperidol (287 residents, or 10.6 percent), quetiapine (260 residents, or 9.6 percent), and thioridazine (103 residents, or 3.8 percent). Second-generation antipsychotics accounted for 79.5 percent of prescriptions (2,162 residents).

Using the chi square test, we examined the likelihood of receiving second-generation antipsychotics on the basis of residents' race and gender and the location of the nursing home. African-American residents were significantly less likely to receive second-generation antipsychotics than Caucasians (290 residents, or 70.5 percent, compared with 1,807 residents, or 81.3 percent; (χ2=23.98, df=1, p<.01). Receipt of second-generation antipsychotics varied significantly by nursing home location (χ2=33.22, df=4, p<.001). Although a majority of patients in all health maintenance areas received second-generation antipsychotics, these medications were most common in the central, urban health maintenance area and least common in the southwest, rural health maintenance area. Using a t test to examine the relationship between age and receipt of second-generation antipsychotics, we found that residents who received second-generation antipsychotics were older than those receiving first-generation antipsychotics (81.6 compared with 82.7 years, t=2.7, df=795, p<.01).

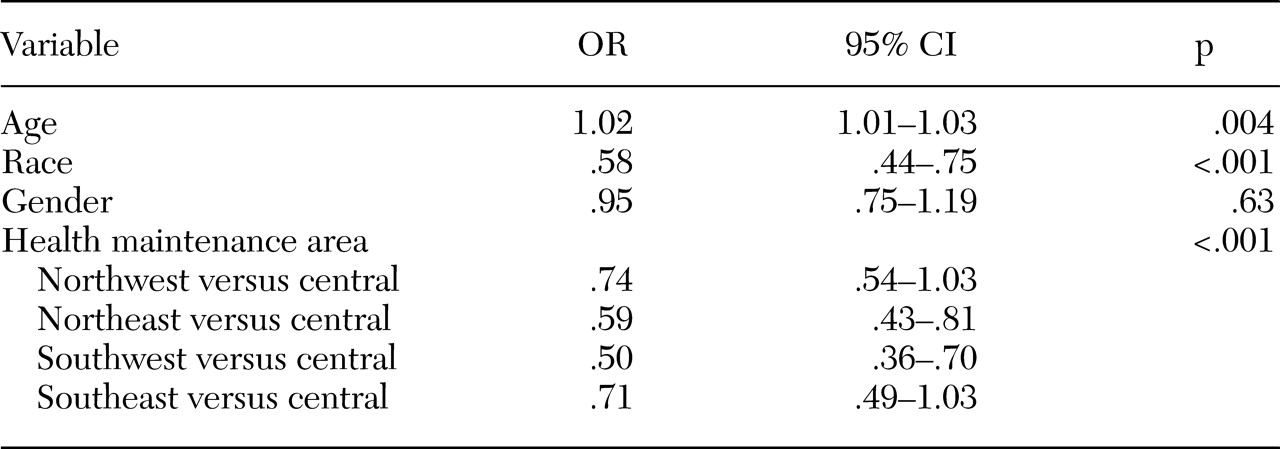

In the logistic regression model (

Table 1), older age and Caucasian race were positively associated with the likelihood of receiving second-generation antipsychotics. Use of second-generation antipsychotics varied significantly by health maintenance area. When the central health maintenance area was used as the referent group, residents of nursing homes in both northeast and southwest Arkansas were less likely to receive second-generation antipsychotics. No significant differences in receipt of medication were found between the referent group and residents in the northwest or southeast corners of the state.

Discussion and conclusions

On the basis of these data, it appears that African-American residents of Arkansas nursing homes are less likely to receive second-generation antipsychotic medications. This finding is consistent with studies of the use of these medications among patients who have schizophrenia and with other studies that have documented health care disparities in elderly populations. Schneider and colleagues (

5) examined racial disparities in the quality of care among enrollees in Medicare managed care health plans. African Americans were less likely than Caucasians to receive breast cancer screening, eye examinations for patients with diabetes, beta-blockers after a myocardial infarction, and follow-up care after hospitalization for mental illness.

Our data showed that older age was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving second-generation antipsychotics. Although this finding was statistically significant, it is unlikely to be clinically significant. The mean age of residents who were receiving first-generation antipsychotics was 81.5 years, compared with 82.6 for those receiving second-generation agents.

We also noted a difference in the likelihood of receiving second-generation antipsychotics on the basis of nursing home location. The central health maintenance area covers the state capital, Little Rock, and is the state's most populous region. It contains the greatest number of mental and physical health professionals. The population in this area and in the northwest health maintenance area is primarily Caucasian, so it is not surprising that we found no difference in patterns of medication use by race. However, although the population of the southeast health maintenance area is primarily African American, there was no difference in likelihood of receiving antipsychotic medications for patients in this area compared with the central health maintenance area. This result suggests that location may not be a good indicator of market penetration and that it needs further study.

This study was limited by the use of claims data. We were not able to use clinical information such as diagnosis, comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions, severity of symptoms, and length of stay in each facility because of the nature of the contract. Thus other aspects of care may have accounted for the differences we found in the use of antipsychotics. One of the most obvious explanations is economic differences that are often associated with race. However, the patients in this study were all Medicaid recipients, and Arkansas places no restriction on the number of medications that can be dispensed each month for nursing home residents. Use of managed care plans could also have influenced our results. However, there is low market penetration of managed care in Arkansas, and the state does not require individuals who are eligible for Medicaid and Medicare to enroll in a Medicare managed care plan. Thus we do not believe systematic differences in insurance coverage explain the differences in antipsychotic use.

It is possible that African-American participants in this study had comorbid illnesses such as diabetes that would be a relative contraindication to the use of certain second-generation antipsychotics, which are associated with various metabolic disturbances, including weight gain, hyperglycemia, and diabetes. The epidemiology of these diseases suggests that hyperglycemia and diabetes induced by antipsychotics could be especially detrimental to African-American patients, because they are common in this population (

6). The literature documenting metabolic effects of second-generation antipsychotics was emerging near the time these data were collected, so this may not be an adequate explanation for differences.

Although it is likely that the most common indication for use of antipsychotic medications in this cohort was psychotic symptoms associated with dementia, some patients may have had other psychiatric diagnoses, such as schizophrenia. If this were the case, it would explain any differences in antipsychotic dosage, but it does not adequately account for a systematic difference in type of antipsychotic. Other published studies suggest that in community-dwelling adult cohorts, African Americans are more likely to receive a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder rather than an affective disorder compared with Caucasians (

7). If a similar diagnostic bias existed for nursing home residents, one would expect higher antipsychotic dosages among African-American residents, but this would not explain the differences in use of second-generation antipsychotics.

Despite the limitations of claims analyses, these findings raise questions about disparities in care and the potential impact on quality of medication management among nursing home residents with psychotic symptoms. African-American residents who could benefit from second-generation antipsychotics may not have access to them. Future studies should include clinical data as well as markers for other socioeconomic differences.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded through a contract with the division of medical services of the Arkansas Department of Human Services. The authors thank Irving Kuo, M.D., Becky Doan, M.S.W., Susan Green, B.A., Kim Smith, Pharm.D., Tina Minden, Pharm.D., Carol Coleman-Kennedy, R.N., Patricia Wright, R.N., Kristi Nelms, and Ann Adams.