Introduction by the column editor: In this article, the Johnson & Johnson—Dartmouth team describes how it has collaborated with six states and the District of Columbia to disseminate the evidence-based practice of supportive employment. Usually, this column presents examples of evolving efforts to identify best practices for treating persons with psychiatric disorders. This month's column is different, because it begins with an established best practice—supported employment—and describes how such a practice can be implemented in the field. The team has suggested a best practice for disseminating a best practice! In this brief description, the magnitude of what the team has accomplished may not be fully evident. Moving the field to adapt to a best practice is easier said than done. Efforts in this direction have failed more often than succeeded. The project also demonstrates how academia and industry can collaborate in a productive and scientifically sound fashion to yield desired outcomes for all stakeholders.

Supported employment has emerged rapidly since the 1980s as an evidence-based service that supports recovery for people with psychiatric disabilities (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5). Despite the existence of clear scientific support and interest from policy experts, provider organizations, and advocates, implementing supported employment and other evidence-based practices has proceeded slowly, and evidence-based supported employment services are therefore not widely available (

6).

The barriers to dissemination and implementation of supported employment are legion: organizational and fiscal separation of the mental health and vocational rehabilitation systems at federal, state, and local levels; disproportionate funding from the federal-state vocational rehabilitation system allocated to assessment and other preemployment activities; discordant measures of vocational success in mental health and vocational rehabilitation; minimal state mental health funding for vocational services; and Medicaid statutes that preclude reimbursement for some aspects of vocational services (

6). Although the evidence clearly supports integrating mental health and vocational services (

7), the de facto separation of service systems is reinforced by bureaucracy, service organization, policies, regulations, personnel, and training, as well as funding (

6).

This column describes a private-public-academic collaboration designed to disseminate evidence-based supported employment for persons with psychiatric disabilities by using best practices for program implementation.

The program

The Johnson & Johnson division of corporate contributions, following the company's credo to "encourage civic improvements and better health," demonstrates social responsibility by funding signature programs in health care, such as Project Head Start (

8). In the late 1990s, senior executives at Johnson & Johnson decided to expand their health promotion initiatives into the mental health area. Leaders from the National Alliance for Mental Illness and the National Institute of Mental Health urged them to consider supported employment programs for people with psychiatric disabilities. With assistance from supported employment researchers at Dartmouth Medical School, Johnson & Johnson executives began a series of discussions with advocates, mental health and vocational rehabilitation leaders, and dissemination and policy experts about how to increase the availability of effective supported employment for people with psychiatric disabilities.

The project emphasized several best practices in implementation (

9). First, because many of the known barriers to the adoption of supported employment stem from separate administrative organizations for mental health and vocational rehabilitation services, the state departments of mental health and vocational rehabilitation collaborated closely on modifying regulations, addressing organizational and funding barriers, and communicating with local providers. Collaboration at the state level was accomplished through regular meetings and joint decisions on regulations, contracts, and policies. Second, because dissemination efforts often fail to address longitudinal training and supervision, each state planned for long-term technical assistance and supervision for participating local agencies. Each state designated a specific implementation specialist, sometimes in collaboration with a local university, to oversee implementation according to established standards of fidelity (

5).

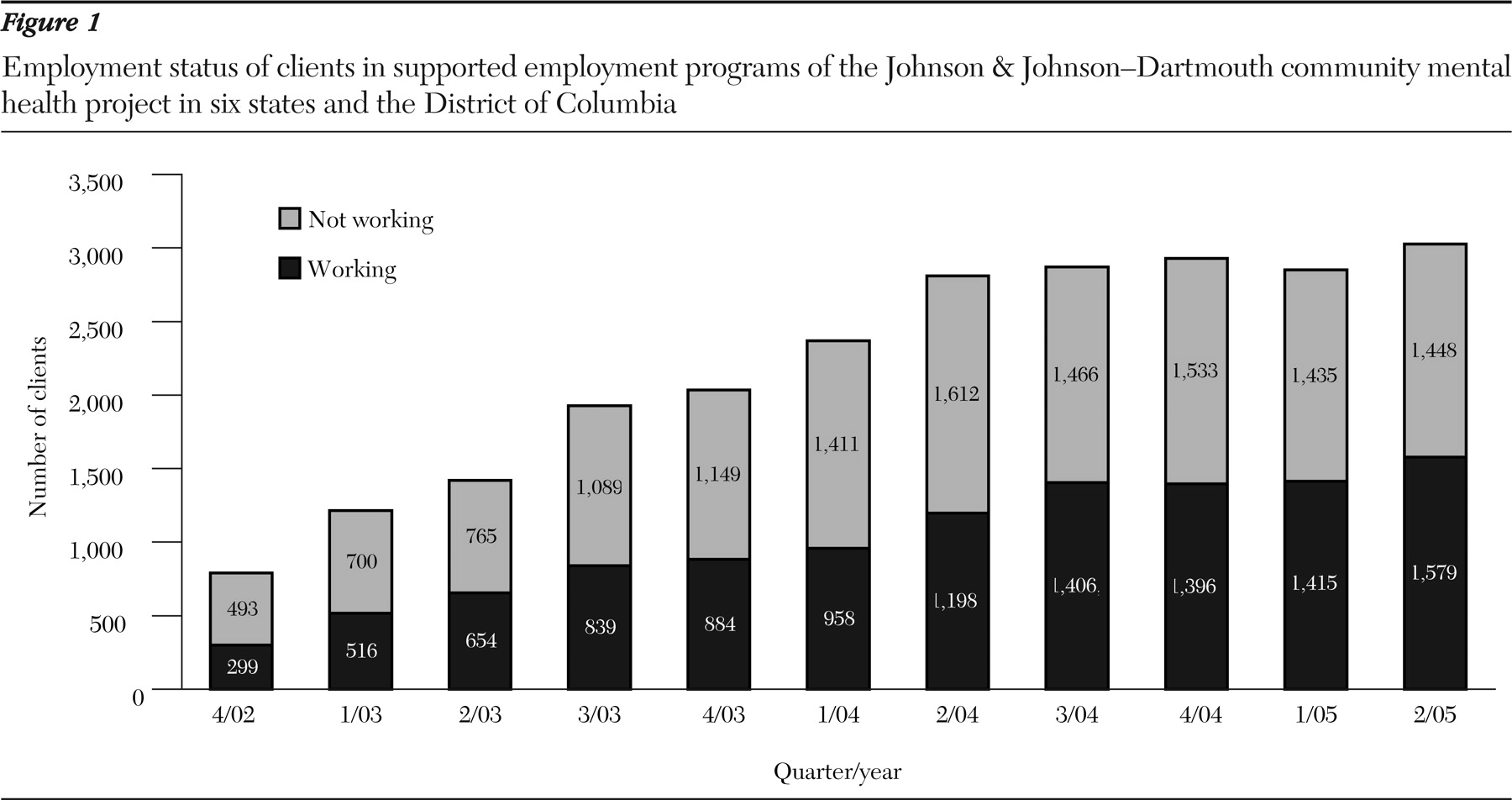

Third, because programs often lack the basic outcome data needed for quality improvement, each agency agreed to keep track of the number of clients served and the number competitively employed during each quarter. Using these simple numbers, supervisors can focus on improving outcomes. Fourth, because local agencies represent complex microsystems, local leadership teams of vocational rehabilitation staff, mental health staff, and advocates identified specific impediments to implementation and developed local strategies to overcome barriers.

After demonstrating feasibility with a small one-year pilot, the Johnson & Johnson—Dartmouth team identified seven states (actually six states and one federal jurisdiction, the District of Columbia) that publicly expressed interest in implementing supported employment services. Choosing implementation sites on the basis of their motivation to participate can be considered another implementation strategy. The full initiative began in 2002 in these seven demographically and economically diverse states—Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Kansas, Maryland, Oregon, South Carolina, and Vermont.

Each state received a small three-year grant with the agreement that the departments of mental health and vocational rehabilitation would match the grant funds and collaborate fully to implement supported employment programs in at least three local areas. The Dartmouth supported employment team provided initial training, consultation, site visits, feedback about fidelity to evidence-based supported employment practices, training for local trainers, and conference calls to link participating state-level trainers.

The seven state grantees identified 26 local program implementation sites, which differed widely in their settings, resources, barriers, and service environments. For example, some of the states were predominantly rural, and others were urban, and some states used fee-for-service financing, whereas others used capitation financing. The 26 local sites had a variety of preexisting vocational programs. With assistance from state-level trainers, leadership teams developed a unique range of approaches to staffing, organizing, training, and monitoring programs. Successful strategies attended to common issues: leadership; financing; organizational processes; outcomes-based supervision; involvement of the business community, families, and consumers; cooperation between mental health and vocational rehabilitation workers; and overcoming rigid regulations, stigma, and misconceptions of employers.

Outcomes

Each state collected outcome data from local programs on the number of mental health consumers who received supported employment at Johnson & Johnson—Dartmouth sites and on the rate of competitive employment at each site. In addition to collecting these data across states, Dartmouth staff interviewed team leaders and state-level trainers about barriers and strategies.

Access to supported employment services improved dramatically in each state, as administrators at the participating sites learned how to add vocational staff and expand their programs. As shown in

Figure 1, the number of clients served at the participating sites increased steadily over 11 quarters, and the proportion of clients who were competitively employed stayed consistently over 40 percent, with the result that the total number of clients in competitive employment also increased steadily. As reported elsewhere (

10), the overall rate of competitive employment was related to local unemployment levels and fidelity to the principles of supported employment. Furthermore, supported employment continued to expand beyond the Johnson & Johnson—Dartmouth sites in every state.

Comments and conclusions

Dissemination of innovative programs is necessarily complex, in part because individual agencies represent idiosyncratic, complex microsystems, each requiring specifically tailored approaches. The best practices of dissemination that were used in this program were collaborative state-level administrative oversight, longitudinal training based on established fidelity criteria, outcome-based supervision, problem solving by local experts, and selection of intervention sites based on motivation to participate.

This initiative addressed real-world dissemination, not controlled research. No attempt was made to impose experimental procedures, to control client entry, or to collect research-quality data. Although the employment numbers reported here could be distorted by program bias or unreliability, they are in accord with observations of trainers and site visitors, and they are consistent with other demonstration programs (

5). Other changes in the health care environment, such as the national emphasis on evidence-based practices, and budget crises in nearly all states, occurred simultaneously, and the findings could be confounded by temporal and maturational factors. Allowing for some degree of error, the findings nonetheless show that by using best-practice approaches to dissemination, supported employment can be rapidly implemented while maintaining outcomes that are consistent with those from research projects.

Many large U.S.-based corporations aspire to demonstrate social responsibility, using various strategies, ranging from employee volunteerism to endowing their own foundations. This project illustrates that corporate philanthropy can be issue driven rather than product driven and that industry's emphasis on outcomes can be combined with academia's emphasis on research-based interventions to enhance public services.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by a gift from the Johnson & Johnson division of corporate contributions.