Introduction

Self-conscious affects, particularly shame and guilt, have been discussed by many researchers and scholars.

Tracy and Robbins (2004), distinguishing self-conscious affects from basic emotions, defined the natures of four self-conscious affects, i.e. guilt, shame, achievement-oriented pride, and hubristic pride. According to them, stable-awareness and self-representation are required for emergence of self-conscious affects. They further wrote that guilt and shame are elicited by appraisals of identity-goal incongruence, whereas pride is elicited by appraisals of identity-goal congruence. Both shame and guilt are framed as moral affects (

Ausubel, 1955). As Tangney, Wagner, and Gramzow (

1992a) noted, “these experiences involve both affective and cognitive components, the latter of which can be conceptualized in attribution terms” (p. 470). These affects are the results of internal attribution (

Tangney, 1990;

Tangney, 1992a). The difference between these two affects is that guilt is remorse for actions taken, whereas shame is an affect that attributes the negative event to one’s entire self (

Lewis, 1971).

Since

Lewis (1971) published

Shame and Guilt in Neurosis, many researchers have undertaken empirical studies to explore the role of shame and guilt in the development of psychological maladjustment (

Tangney, 1996). Most studies showed that shame is related to a variety of psycho pathologies, such as eating disorder (

Frank, 1991), depression (

Andrews, 1995;

Grabe, Hyde & Lindberg, 2007;

Harper & Arias, 2004;

Luby, Belden, Sullivan, Hayen, McCadney & Spitznagel, 2009;

Stuewig & McCloskey, 2005;

Thompson & Berenbaum, 2006), anger (

Harper & Arias, 2004), social phobia (

Helsel, 2005), borderline personality disorder (

Rüsch, Lieb, Göttler, Hermann, Schramm, Richter, Jacob, Corrigan & Bohus, 2007), and posttraumatic stress disorder following sexual abuse (

Feiring & Taska, 2005). Some other studies comparing shame with guilt demonstrated that shame is one of the crucial factors in the development of anger arousal, resentment, irritability, a tendency to blame others, somatization, obsessive compulsive disorder, interpersonal sensitivity, low other-oriented empathetic responsiveness, self-oriented personal distress, anxiety, hostility, depression, and psychoticism (Rüsch, et al., 1997;

Tangney et al., 1992a, Tangney, Wagner & Fletcher & Gramzow, 1992b,

Tangney, 1991;

Tangney & Dearing, 2002a,

Tangney, Stuewig & Mashek, 2007;

Wright, O’Leary & Balkin, 1989). These comparisons indicate that shame can cause more pain than guilt. Shame is characterized not only criticism by the entire self, but also by sensitivity to being exposed to surroundings. The latter characteristic is noted by

Benedict’s (1967) definition of shame as an external sanction, and

Inoue’s (1977) definition of “public shame,” which is experienced as a result of judgment by the membership group. It appears that people prone to shame cannot bear self-criticism because of extremely low self-esteem (

Tangney & Dearing, 2002b,

Rüsch et al., 2007), and as a result they project their criticizing self on their surroundings and feel as though they are being criticized by others.

In the realm of self-psychology,

Kohut (1972) argued that without the mother’s approval and admiration, a crude and intensely narcissistic cathexis of the grandiose self cannot be transformed nor integrated with the remainder of the psyche. It is either split off or repressed. When these defense mechanisms do not function because of archaic claims made by one’s exhibitionistic self, the ego is flooded by this self and becomes paralyzed, consequently feeling intense shame and rage.

In accordance with Freud’s theory on the contribution of guilt to melancholy (

Freud, 1917), some studies have shown psychopathological aspect of guilt (

Frank, 1991;

Luby, et al., 2009). When compared with shame, the psychopathology-prophylactic effect of guilt has been emphasized, such as its inverse relationship with delinquent behavior, externalization of blame, anger, hostility, and resentment (

Stuewig & McCloskey, 2005;

Tangney et al., 1992a,

Tangney et al., 1992b), as well as its positive relationship with other-oriented empathetic responsiveness (

Tangney, 1991).

As defined by

Lewis (1971), guilt is remorse for one’s previous actions as experienced through introspection. This process depends on intellectual contemplation (

Sterba, 1934), one of the crucial ego functions that helps an individual observe his own behavior and leads to self-understanding, modification of future actions, and higher self-efficacy.

In this study, our first aim was to examine which self-conscious affect is more adaptive, i.e., which self-conscious affect is based on an adaptive cognition. “Resilience” was chosen as an index of adaptive ability. The concept of resilience has been the focus of attention in the realms of social psychology and psychiatry since the 1970s as one of the personal attributes that prevents people from developing psychological maladjustment as a result of stressful life situations (

Haui, Igarashi, Shikai, Shono, Nagata & Kitamura, 2009). Rutter (1985) noted that

resilience is characterized by some sort of action with a definite aim in mind and some sort of strategy of how to achieve the chosen objective which seems to involve several related elements: firstly, a sense of selfesteem and self-confidence, secondly, a belief in one’s own self-efficacy and ability to deal with change and adaptation, and thirdly, repertoire of social problem-solving approaches (p. 607).

It is not a fixed characteristic but changes throughout life, as pointed out by Rutter (1985), “its quality is influenced by early life experiences, by happenings during later childhood and adolescence, and by circumstances in adult life (p. 608).”

Wagnild and Young (1993), defining resilience as “a personality characteristic that moderates the negative effect of stress and promotes adaptation” (p. 165), developed the Resilience Scale (RS), which was used in this study.

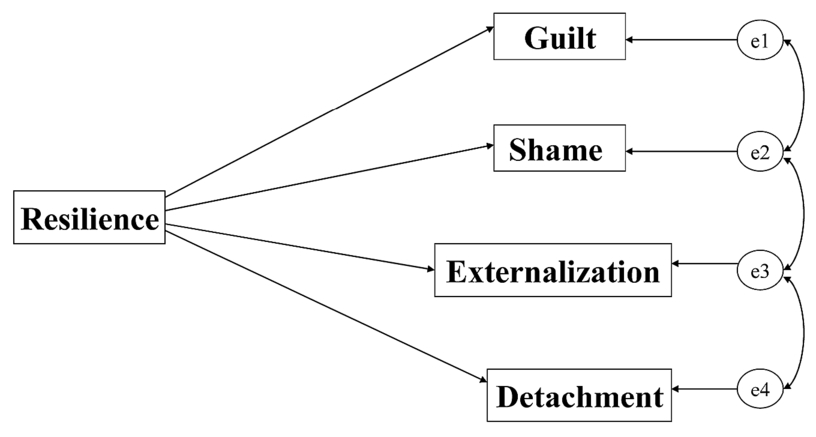

In this study, for assessing self-conscious affects, we adopted the Test of Self-Conscious Affect-3 (TOSCA-3). The Test of Self-Conscious Affect was developed by

Tangney and Dearing (2002c), based on

Lewis’s (1971) definition of guilt and shame, and was revised twice to solve a few flaws, leading to the development of TOSCA-3 (Tangney, Dearing, Wagner & Gramzow, 2000). As noted earlier, using TOSCA and TOSCA-3, Tangney and her colleague showed that in comparison with guilt, shame contributes to a variety of psychopathologies, which is consistent with the theories of shame and guilt. In particular, the relationship between shame and anger, verified by Tangney and her colleagues, may be associated with the narcissistic rage following painful shame caused by maternal rejection (

Kohut, 1972). The Test of Self-Conscious Affect-3 enables us to assess not only guilt and shame, but also externalization and detachment, which seem to focus on cognition rather than affect. At first glance, externalization and detachment are not related to self-representations. However, they may be elicited when an individual’s identity is threatened, for example, when he or she is insulted by another (

Tracy & Robbins, 2004) or when self-esteem is shaken because of a failure in a role that serves to maintain identity. We can infer from this that these two cognitive styles are reactions against the painful internal attribution.

The first of our hypotheses is: Because shame is a painful experience regarded as being related to psychopathologies, it is a maladaptive affect. In other words, an individual with low resilience is more likely to be prone to feel shame. As noted previously, externalization and detachment are reactions against painful internal attributions; these two seem to be more adaptive than shame, i.e., people with high resilience can utilize these cognitions. In TOSCA-3 guilt may have an ameliorative characteristic that facilitates an individual’s modification of future actions. Therefore, we presumed that guilt is driven from high resilience. When compared with people who are prone to externalization and detachment, a guilt-prone person can endure internal attribution, thus guilt appears to be a more mature cognition than externalization and detachment. Guilt seems to be the most adaptive of the four cognitions that derive from negative interpretations of the scenarios in TOSCA-3.

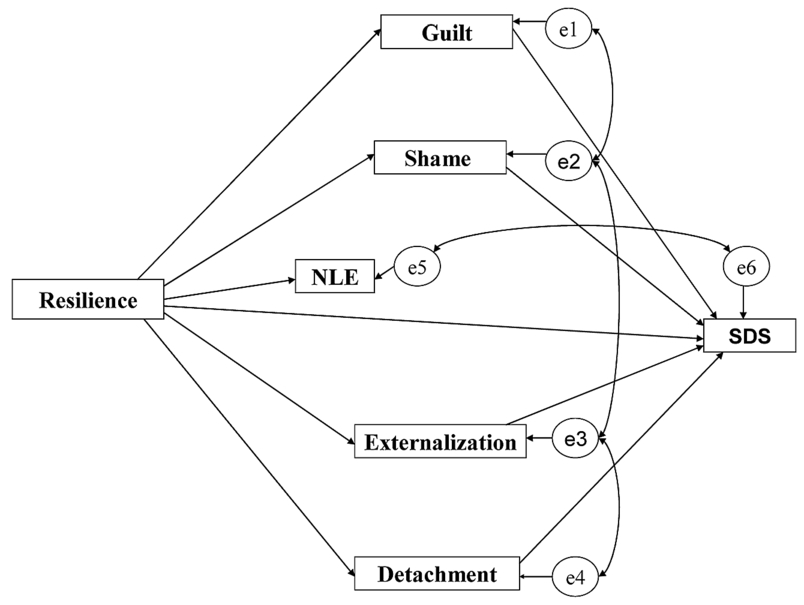

The second aim of this study was to explore how the two concepts mentioned above, resilience and self-conscious affects, influence depressive mood. Depression has been studied in relation to several factors, including temperament (

Finch & Graziano, 2001), personality (

Potthoff, Holahan & Joiner, 1995;

Saudino, McClearn, Pedersen, Lichtenstein & Plomin, 1997), early perceived parenting (

Parker, 1979), childhood adversity (

Buist, 1998;

Maughan & McCarthy, 1997), social support (

Finch & Graziano, 2001;

Mohr, Classen & Barrera, 2004,

Suttajit, Punpuing, Jirapramukpitak, Tangchonlatip, Darawuttimaprakorn, Stewart, Dewey, Prince & Abas, 2010), self-efficacy (

Maciejewski, Prigerson & Mazure, 2000), and a negative life event (NLE) (Maciejewski, et al., 2000;

Potthoff et al., 1995;

Saudino, et al., 1997).

These have been regarded as crucial factors that influence the onset and severity of depression. In particular, the relationship between an NLE and depression has not been understood as unidirectional, rather as bidirectional, namely, an NLE makes an individual depressed, and then a depressed individual actually generates an NLE, which leads to a more severe depression (

Hammen, 1991). Resilience has been discussed in preventing depression (

Aorian, Shappler-Morris, Neary, Spitzer & Tran. 1997;

Aorian, K. J. & Norris, 2000;

Heilemann, Lee & Kury, 2002;

Miller & Chandler, 2002;

Wagnild & Young, 1993). In this study, we explored the influence of resilience, an NLE, and self-conscious affects on depression, taking into account the causal relationship between resilience and self-conscious affects and the bidirectional relationship between an NLE and depression.

Our second hypothesis is that the causal relationship between resilience and depression is partially mediated by self-conscious affects, which means the pathway from low resilience to a depressive mood is determined partially by the cognitive styles on which self-conscious affects are based. Low resilience induces an individual to shame and as a result, he is more likely to become depressed. On the other hand, high resilience induces an individual to guilt, and as a result, reduces depressive mood. Furthermore, we presumed that a significant correlation would be identified between an NLE and the depressive mood.

Based on the above, we summarized our research questions as follows:

1:

Which of the two self-conscious moral affects—shame or guilt—is based on a more adaptive cognition? What roles do detachment and externalization have in terms of adaptation to one’s environment?

2:

Is a depressive mood resulting from a low-resilience partially mediated by a maladaptive cognition that precedes particular self-conscious affects?

Discussion

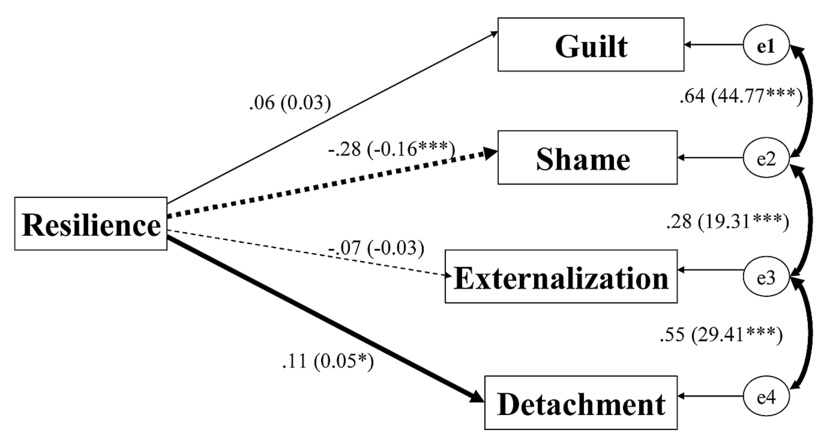

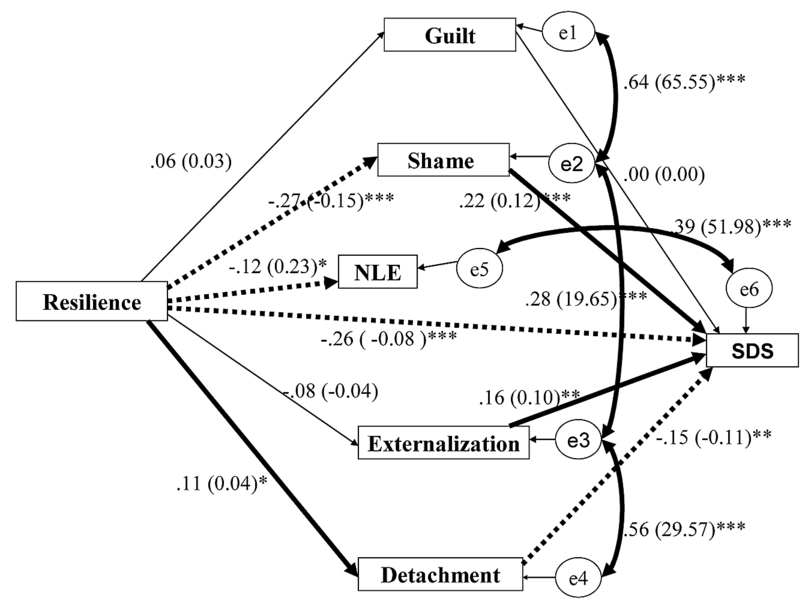

This study showed that a resilient individual is more likely to employ detachment and tends less towards shame-proneness. Resilience also prevents one from entering a depressive mood. Furthermore, shame-proneness increases the depressive level whereas detachment does the opposite. These results will be discussed with a successive focus on each affect.

First, guilt-proneness was related to neither resilience nor depressive level. The lack of a significant causal relationship to resilience means that guilt-proneness cannot be simply considered as either adaptive or maladaptive, or successful or unsuccessful. As noted in the introduction, guilt is an affect that helps individuals introspect and criticize their own previous actions. In this regard, guilt may be a painful experience. Therefore, it may threaten an individual’s mental balance and can be regarded as unsuccessful. However, we can also look at this from a different viewpoint. Introspection of one’s actions might persuade an individual that he or she could modify actions if put in similar stressful situations in the future. In other words, the individual would have a higher degree of self-efficacy that would help him or her adapt to the environment. From this perspective, guilt could be regarded as adoptive. It is probable that these two contradictory aspects of guilt offset each other in their relation to resilience. Next, we discuss the finding that guilt lacks a significant relationship to a depressive mood.

Luby, et al. (2009) concluded that increasing depression severity is associated with less frequent attempts at guilt reparation. Therefore, whether the guilt-proneness causes a depressive mood may depend on whether an individual is able to make reparation for a failure.

Second, shame-proneness had an inverse causal relationship with resilience and a direct causal relationship with a depressive mood. Therefore, resilience had an influence on depressive mood by way of shame-proneness. An inverse relationship between shame-proneness and resilience implies that shame-proneness is maladaptive, and it can worsen an individual’s depressive mood. As explained in the introduction, shame drives an individual to criticize the entire self. This self-criticism can be a more painful experience than guilt. Therefore, it is hard for individuals who feel shame to endure self-criticism, and they project the criticizing self onto others. Although they succeed in shifting judgment to others, they, in turn, always have to worry about how they might be perceived, which surely is an uncomfortable experience. Therefore, this affect helps an individual not feel psychological pain, but it fails and provokes a different stress. It is understandable that less resilient individuals are more likely to feel shame-proneness. Furthermore, shame does not induce an individual to modify his future actions because he is not introspective and refers self-judgment to others. This process decreases self-efficacy and increases depressive mood. Furthermore, for shame-prone people, it might be difficult to confide distress, which does not help alleviate it. This view is endorsed in a study by

Hook and Andrews (2005), which showed patients’ shame was the most frequent reason for concealing depression-related symptoms and behaviors or other distressing experiences from their therapists.

Third, externalization did not relate to resilience. As noted in introduction, externalizing blame for a failure is helpful for maintaining selfesteem, and most people would adopt this attributing style. It would seem that externalizing the cause of negative life events would help an individual alleviate psychological pain because it avoids internal attribution; however, if this attribution is overused, it cannot be said to be adaptive because it would not lead an individual to behavioral modification and would cause friction with their surroundings. These opposing factors may explain the lack of a causal relationship between resilience and externalization. However, though both externalization and detachment are not based on internal attributions, externalization directly influenced depressive mood, which is in contrast to the finding that detachment alleviated a depressive mood.

Last, this study showed that the more resilient an individual is, the more likely he is to use detachment. Detachment also decreased depressive mood. Therefore, depressive mood was indirectly influenced by resilience by way of detachment. Detachment helps an individual avoid current psychological pain, which mirrors some researchers’ descriptions of the role of resilience in helping an individual to avoid the deleterious effect of stress (

Wagnild & Young, 1993). Detachment decreases an individual’s depressive mood because it enables a denial of responsibility, therefore facilitating mental balance. It may be possible that temporary detachment would help an individual keep mental balance, however, it is questionable that long-term detachment from an NLE would bring about psychological health. In addition, whether the detachment is adaptive or maladaptive depends on the nature of the stressful situation in which an individual applies it. We should conclude that an individual who is apt to apply detachment in the given situation presented in TOSCA-3, is more resilient and less easily led to a depressive mood. In this study we adopted depressive mood as a variable that assesses psychological health. However, a different result would have been obtained if we had chosen other variables, such as psychological well-being (

Ryff, 1989) or psychological growth (

Tedaschi & Calhoun, 1996).

We should further discuss the relationship between resilience, negative life event, and depressive mood. Resilience inversely affected the impact of NLEs (standardized causal coefficient from resilience to NLE was -.12, p < .05;

Fig. 4). This suggests that less resilient individuals perceive negative life events more seriously or, less resilient individuals actively generate serious NLEs as a result of poor coping strategies and an inability to adapt. Resilience also inversely influenced the SDS score (standardized causal coefficient from resilience to SDS was –.26, p < .001;

Fig. 4), which means that resilience has a protective factor against depressive mood. This was consistent with previous studies, as referred to in the introduction.

The impact of an NLE was positively correlated with SDS (

Table 3,

Fig. 4). This was endorsed by many previous studies that showed that not only does an NLE cause an individual’s depression but also that a depressed individual perceives an NLE more seriously than a person who is not depressed and on occasion even actively generates an NLE (

Daley, Hammen, Burge, Davila, Paley, Lindberg & Herzberg, 1997;

Davila, Hammen, Paley & Daley, 1995;

Hammen, 1991; Potthoff, et al., 1995;

Simons, Angell, Monroe & Thase, 1993).

A few limitations of this study should be noted. First, TOSCA-3 is a questionnaire that assesses the way an individual would recognize and perceive events in the provided scenarios. In other words, the affects and attributions that respondents state they would feel in the given situations could be different from those they would feel if the events actually occurred. Second, for assessing the severity of an NLE, only the respondents’ subjective evaluating score was adopted, that is, it was not confirmed objectively. If we had evaluated the NLE objectively, we would have been able to judge whether or not significant relationship between the NLE and the SDS scores is, in part, the product of the respondents’ deviated cognition. Furthermore, respondents provided a large variety of NLEs including academic stress, difficulties with interpersonal relationships, and personal medical issues. This study was not based on face-to-face interviews. Therefore, we were unable to obtain detailed information concerning the nature nor were we able to classify in terms of characteristics of the NLEs provided by the respondents. Third, a shortcoming of this study is the sample quality. We targeted only university students. A wider distribution of demographic characteristics would have been preferable. Also, if a sample from a clinical population had been used, different results on the relationships between resilience, the self-conscious affects, and the depressive mood would have been identified. Among the 642 eligible students, were the 195 students who did not attended at least one class, or who attended but declined to participate in the study, are more likely to suffer from a severe NLE and/or a depressed mood. This potentially affected the results.

The clinical implications of this study should be noted. When we see patients who are prone to detachment in response to a previous NLE, we should understand that self-introspection could lead them to a depressive state. They are using this cognition to maintain their mental balance. Therefore, we should not prompt them to take responsibilities, but instead support them until they are able to attribute the NLE internally.

For shame-prone person, who is apt to self-criticism, we should focus on his good points and elevate his self-esteem. This would prevent him from becoming severely depressed. The idea that guilt is a mature affect, and the others are immature and related with psychopathologies should be avoided.

Furthermore, the correlation between an NLE and a depressive mood may be the result of the one of the three following possibilities, or a combination of two or all of them:

First, not only does an NLE cause depression, but a depressed individual is more likely to define an experience as an NLE than a person who is not depressed

Second, a depressed individual perceives an NLE more severely than a one who is not depressed.

Third, a depressed individual actively generates an NLE through distorted cognition, which is followed by inappropriate interpersonal behavior, such as reassurance seeking (Daley, et al., 1997;

Davila et al., 1995;

Hammen, 1991; Potthoff, et al., 1995;

Simons, et al., 1993).

Therefore, pharmacological treatment on its own does not help an individual recover from depression. That is to say, deviated cognition and behavior accompanying depression should be dealt with by a therapist’s support. This leads to less severe and less frequent NLEs, and in turn, a reduction in the severity of depression. The viscous circle of depressive mood, cognitive distortion, maladaptive coping, and NLEs should be broken.

In sum, this study examined the relationship between resilience, the four self-conscious affects and depressive mood, and showed that a “nonmoral” affect, such as detachment, is not necessarily an unsuccessful attribution, and a moral affect, such as shame fails at keeping mental balance.