RO-DBT Treatment Modes and Targets

The functions and modes of outpatient RO-DBT are similar to those in standard DBT (

Linehan, 1993a), including weekly one hour individual therapy sessions, weekly skills training classes, telephone coaching (as needed), and weekly therapist consultation team meetings (over a period of ~30 weeks). The primary target/goal in RO-DBT is to decrease severe behavioral over-control, emotional loneliness, and aloofness/distance

rather than decrease severe behavioral dyscontrol and mood dependent responding as in standard DBT.

RO-DBT Orientation and Commitment

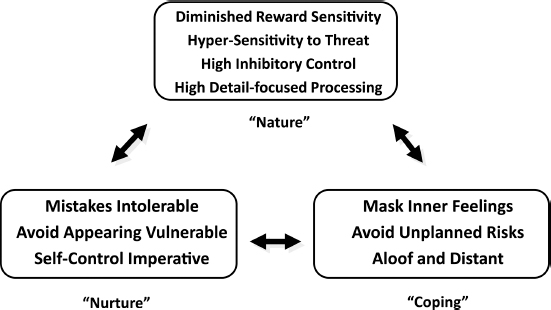

The orientation and commitment stage of RO-DBT takes up to four sessions and includes five key components: 1) confirming self-identification of over-control as the core problem, 2) obtaining a commitment from the client to discuss in-person desires to drop-out of treatment before dropping-out, 3) orienting the client to the RO-DBT neurobiosocial theory of over-control, and 4) orienting the client to the RO-DBT key mechanism of change—i.e., open expression = increased trust = social connectedness. A major aim of the orientation and commitment stage of RO-DBT is to identify collaboratively the factors that may be preventing the client from living according to their valued-goals. Values are the principles or standards a person considers important in life that guide behavior—e.g. to raise a family, to be a warm and helpful parent to one’s children, to be gainfully and happily employed, to develop or improve close relationships, to form a romantic partnership. Whereas, goals are the means by which a personal value is achieved—e.g. working collaboratively on projects or household chores in a manner that respects individual differences and appreciates each person’s contributions. From here, the therapist can begin the process of identifying and individualizing treatment targets. Treatment targets in RO-DBT prioritize maladaptive social-signaling behaviors that function to ostracize the client and exacerbate emotional loneliness. For example, repeatedly re-doing other people’s work (e.g., re-wording an email, repacking the dishwasher) sends a powerful social-signal (e.g., that others are incompetent or cannot be trusted) that negatively impacts achievement of valued-goals related to social connectedness. Thus, “re-doing” is an obstacle because it demoralizes coworkers and family members, while exhausting the client because it means that they are often working harder than nearby others—leading to resentment and burnout. Finally, the orientation and commitment phase involves the start of individualized treatment targets linked to five OC themes—in this case, “re-doing” is linked to the theme “rigid and rule-governed behavior” (see OC themes below).

RO-DBT Individual Therapy Treatment Targets

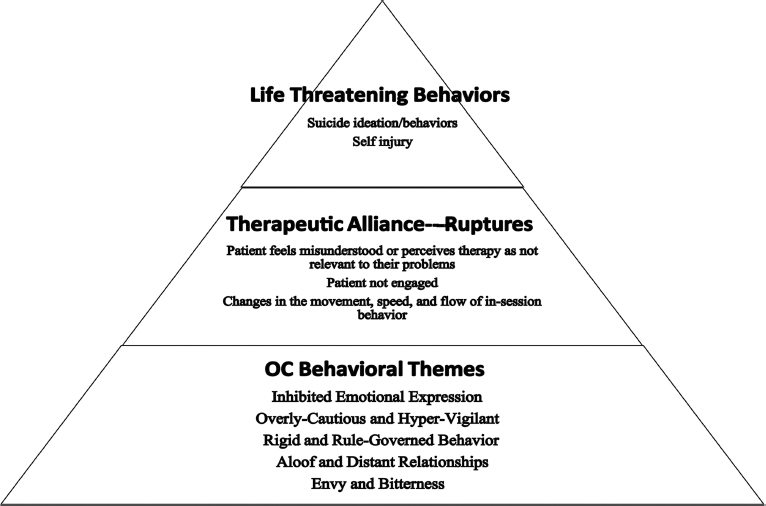

RO-DBT treatment targets are arranged according to a hierarchy of importance; 1) reduce life-threatening behaviors, 2) repair alliance-ruptures, and 3) reduce OC social-signaling deficits and maladaptive overt behaviors linked to OC themes (see

Figure 2). Unlike standard DBT, RO-DBT hierarchically targets

therapeutic alliance ruptures over

therapy-interfering behaviors. Alliance-ruptures in RO-DBT are defined as: 1) the client feels misunderstood, and/or 2) the client experiences the treatment as not relevant to their unique problems. This is a major deviation from standard DBT, where therapy-interfering behaviors are considered the second most important target in the treatment hierarchy (after life threatening). Broadly speaking, therapy-interfering behaviors in standard DBT (

Linehan, 1993a) refer to

problem behaviors that interfere with the client receiving the treatment (e.g., non-compliance with diary cards, not showing for sessions, or refusal to speak during a session). In RO-DBT alliance-ruptures

are not considered problems; they are considered essential practice grounds for learning that conflict can be intimacy enhancing. Crucially, clients who are over-controlled need to learn that expressing inner feelings—including those involving conflict or disagreement—is part of normal healthy relationships. Since clients characterized by OC are expert at masking inner feelings, a strong therapeutic alliance is not expected to develop until mid-way through treatment (i.e., –14

th session)—regardless of client statements of commitment or therapist expertise. Consequently, RO-DBT considers it likely that a therapeutic relationship is superficial, if by the 14th session, a therapist/client dyad has

not had multiple alliance-ruptures and repairs. When an alliance rupture is suspected, RO-DBT therapists are taught to adopt a stance of

relaxed, yet engaged, curiosity in order to facilitate a repair. This typically involves seven sequential steps:

1)

Dropping the current agenda or topic being discussed (e.g., chain analysis).

2)

Taking the “heat-off” by briefly disengaging eye-contact. Most OC individuals dislike being the center of attention (i.e., the “limelight”). Heat-off is a skill that involves briefly shifting one’s attention elsewhere in order to allow a hyper-threat sensitive OC client time to self-regulate.

3)

Signaling affection and cooperation by leaning back, taking a slow deep breath, half smiling, and raising one’s eyebrows. Raised eyebrows (or eyebrow wags) are universal signals of liking and social-safety.

4)

Inquiring about the in-session change and encouraging candid disclosure—e.g. “I noticed something just happened” (describe change), then “Did you notice this too? What’s going on with you right now?”

5)

Slowing the pace of the conversation, allowing time for the client to reply to questions, reflecting back what is heard, and confirming that the reflection was accurate.

6)

Reinforcing candid self-disclosure (e.g., thanking them for the “gift of truth”).

7)

Confirming re-engagement by checking in with them before returning back to the original agenda. It is important to keep repairs short (less than 10 minutes) in order to reinforce self-disclosure (recall that clients who over-control dislike the “limelight”).

Though life-threatening and therapeutic-alliance ruptures take precedence when present; the third most important target in the RO-DBT treatment hierarchy pertains to the

reduction of maladaptive OC behaviors linked to five OC behavioral themes. These themes (see

Table 2), specific for OC problems, are used as a framework for structuring the identification of individualized and behaviorally specific OC treatment targets. The key in treatment targeting with OC is for the therapist to continually ask themselves in-session: “

How might this type of social-signaling—e.g. pouting, looking away, flat affect, non-descript use of language, answering a question with a question—impact the formation of a strong social bond?” or “Would this behavior make it more likely or less likely for a person interacting with my client to want or desire to get to know them better?” Thus, treatment targeting and subsequent behavioral chain analyses in RO-DBT

prioritize changing problematic social-signaling deficits that function to reduce social-connectedness (e.g., turning-down help; silent treatment)

over problematic internal experiences (e.g., emotion dysregulation, distorted thinking; experiential avoidance). Individualized targets are monitored daily on diary cards and updated regularly.

RO-DBT Skills Training

Radically Open-DBT skills training classes meet on average for ~30 weekly sessions—with each class lasting approximately 2.5 hours.

Table 3 provides an overview of the RO-DBT skills training lesson plan—including those from standard DBT (

Linehan, 1993b; 2014) that have been adapted for OC problems (identified by

* and italics). Next we review the core theoretical principles underlying radical openness and describe some of the new features in RO-DBT mindfulness skills. The RO-DBT treatment manual provides detailed skills training instructor notes and key teaching points for all of the RO-DBT skills listed in

Table 3—including user friendly handouts/worksheets for clients (

T.R. Lynch, in press).

Core Radical Openness

Radical openness represents the core philosophical principle and core set of skills in RO-DBT. It is based on confluence of three overlapping elements or capacities posited to characterize psychological health: openness, flexibility, and social connectedness (with at least one other person). As a state of mind, it entails a willingness to surrender prior preconceptions about how the world should be in order to adapt to an ever-changing environment. At its most extreme, radical openness involves actively seeking the things one wants to avoid in order to learn. Radical openness alerts us to areas in our life that may need to change while retaining an appreciation for the fact that change is not always needed or optimal.

RO-DBT replaces core Zen principles in standard DBT with those derived from Malamati-Suffism. The Malamatis are not so much interested in the acceptance of reality or seeing “what is” without illusion (central Zen principles), but rather they look to find fault within themselves and question their self-centered desires for power, recognition or self-aggrandizement (Toussulis, 2012). Thus, radical openness involves purposeful self-enquiry and the cultivation of healthy self-doubt. Importantly,

radical openness differs from

radical acceptance taught as part of standard DBT (

Linehan, 1993a). Radical acceptance “is letting go of fighting reality” and “is the way to turn suffering that cannot be tolerated into pain that can be tolerated” (

Linehan, 1993b, pg. 102), whereas

radical openness challenges our perceptions of reality. Indeed, radical openness posits that

we are unable to see things as they are, but instead that we see things as we are because each of us carries perceptual and regulatory biases with us that influence our ability to be receptive and to learn from unexpected or disconfirming information. This way of behaving also contrasts with the concept of wise mind in standard DBT that emphasizes the value of intuitive knowledge, the possibility of fundamentally knowing something as true or valid, and posits inner knowing as “almost always quiet” and to involve a sense of “peace” (

Linehan, 1993b, p. 66). From an RO-DBT perspective, “facts” or “truth” can often be misleading partly because “we don’t know what we don’t know”, things are constantly changing, and there is a great deal of experience occurring outside of our conscious awareness. Truth is considered “

real-yet elusive” –e.g. “If I know anything, it is that I don’t know everything and neither does anyone else” (M. P.

Lynch, 2004; pg. 10). It is the pursuit of truth that matters—not its attainment. Radical openness requires willingness to doubt or question intuition or inner conviction without falling apart.

The practice of radical openness involves three steps: 1) acknowledgment of environmental stimuli that are disconfirming, unexpected, or incongruous, 2) purposeful self-enquiry into habitual or automatic emotion-based response tendencies by asking “Is there something here to learn?” –rather than automatically explaining, justifying, defending, accepting, regulating, re-appraising, distracting, or denying what is happening in order to feel better, and 3) flexibly responding by doing what is needed to be effective in the moment in a manner that signals humility and accounts for the needs of others (e.g., recognizing that what is “effective” for oneself—may not be effective for others; celebrating diversity; signaling a willingness to learn from what the world has to offer; strive for perfection, but stop when feedback suggests that striving is counterproductive or damaging a relationship).

RO-DBT Mindfulness Skills

Mindfulness skills in RO-DBT include new OC states of mind (Fixed-Mind, Flexible-Mind, and Fatalistic-Mind) and new “what” and “how” skills (i.e., Awareness Continuum and “Outing-Oneself” describe skills, “Participate without Planning” skills; “Self-Enquiry” skills, and “with Awareness of Judgments” skills). The new mindfulness states of mind in RO-DBT represent common OC ways of coping—that can be both adaptive and maladaptive depending on the circumstances. For OC individuals two states of mind are most common—both of which are usually maladaptive and occur secondary to disconfirming feedback and/or when confronted with novelty. When challenged or uncertain, the most common OC response is usually to search for a way to minimize, dismiss, or disconfirm feedback in order to maintain a sense of control and order. This style of behaving in RO-DBT is referred to as

fixed mind. Fixed mind is a problem because it says “change is unnecessary because I already know the answer”. The dialectic opposite of fixed mind is

fatalistic mind. Whereas fixed mind involves rigid resistance and energetic opposition to change, fatalistic mind involves giving-up overt attempts at resistance. Fatalistic mind can be expressed by drawn out silences, bitterness, refusals to participate, and/or sudden acquiescence or a literal suspension of goal-directed behavior and shut-down. Fatalistic mind is a problem because it removes personal responsibility by implicating that “change is unnecessary or impossible because there is no answer”. Mindful awareness of these “states” serves as important skill practice reminders.

Flexible mind forms the synthesis between fixed and fatalistic mind states: it involves being radically open to the possibility of change in order to learn, without rejecting one’s past or falling apart. Importantly, although wise mind in standard DBT and flexible mind in RO-DBT share some similar functions, there are also important differences. For example, whereas wise mind celebrates the importance of inner knowing and intuitive knowledge (see

Linehan, 1993b pg. 66), flexible mind celebrates self-enquiry and encourages “healthy self-doubt” and compassionate challenges of our perceptions of reality.

There are two new RO-DBT mindfulness “What” skills. The first is an RO-“describe” skill known as the “Awareness Continuum”, which provides a structured means for a client who is over-controlled to practice revealing inner feelings to another person—without rehearsal or planning in advance what one might say. It also allows practitioners an opportunity to practice how to label and differentiate between thoughts, emotions/feelings, sensations, and images. The second RO-DBT “what” skill is referred to as “Participating without Planning”. This skill involves learning how to passionately participate with others without compulsive rehearsal or obsessive needs to get it ‘right’. Participating without planning practices should be unpredictable (i.e., they begin without any form of forewarning or orientation) and brief (i.e., 60 seconds in duration). For example, the instructor without any forewarning suddenly begins to make a silly face, wave their arms about, while saying; “OK, everyone do what I do! Make a funny face and wave your arms, like this! And this! (changing expression while clucking and flapping like a chicken) There’s nobody here but us chickens! Wow, look at me … I’m speaking nonsense! Blah-Blah. Now say it again. Blah-Blah! Say bloo-blip and blippity-bloop! OK, now say, blippity-be-ba-blipty bloo! ( pause with warm smile, eye contact all around and eyebrows raised) Getting better, LET’s GO LOUDER! Say, OHRAW! SAY OHRAWWW! SAY IT AGAIN…OOOHHHRAWWWW! OK, all together now … LET’S START SPEAKING GOBBLITY-GOOK WHILE WAVING OUR ARMS! IT’S A NEW LANGUAGE! Haven’t you heard? Boo … boo … blickety-block and floppity-flow and mighty so-so!” Instructors should end by clapping their hands in celebration and encourage the class to give themselves a round of applause. “Well done! OK, now sit down and let’s share our observations about our mindfulness practice.” The brief nature of the practice makes it less likely for self-consciousness to arise and more likely for individual members to experience a sense of positive connection or cohesion with the class as a whole—that generalizes outside of the classroom with repeated practice. These practices are an essential tool for teaching clients characterized by over-control how to re-join the tribe.

There are two new RO-DBT mindfulness “How” skills. With “Self-Enquiry” is the core RO-DBT “how” skill and the key for radically open living. It involves actively seeking the things one wants to avoid or may find uncomfortable in order to learn and the cultivation of a willingness to be “wrong”—with an intention to change if needed. Self-enquiry celebrates problems as opportunities for growth—rather than obstacles preventing us from living fully. The core premise underlying self-enquiry stems from two observations: 1) we do not know everything—therefore, we will make mistakes, and 2) in order to learn from our mistakes, we must attend to our error. Rather than seeking equanimity, wisdom, or a sense of peace, self-enquiry helps us learn because there is no assumption that we already know the answer. RO-DBT therapists must practice radical openness and self-enquiry themselves in order to encourage clients to use self-enquiry more deeply. For example, one therapist practiced outing themselves to their client in order to illustrate how Fatalistic-Mind thinking thrives on denial and self-deception by saying:

“Though it is hard to admit … during an argument, say with my partner…. sometimes I purposefully become less talkative or avoid eye contact in order to punish them for not agreeing with me; that is, I pout. If the person I’m with asks me why I am not talking, I usually deny that I am being quiet, yet deep down I know that I am purposefully choosing to talk less. What I find amusing is that the more willing I am to concede to myself or the other person that I am in Fatalistic-Mind, the harder it is for me to keep it up. I have discovered that, for me, pouting can really only exist if I pretend it’s not happening. Once I admit it; even just to myself; I find it difficult to maintain because deliberate pouting is not how I want to behave or deal with conflict. My self-enquiry work around this has helped me live more fully according to my values.”

The willingness of the therapist to reveal weakness without falling apart or harsh self-blame functioned to encourage the client to behave similarly—in this case, the client revealed for the first time that he often secretly tried to undermine others and sometimes lied to obtain a desired goal. The client’s self-disclosure of a previously well-guarded “secret” resulted in the identification of important treatment targets linked to envy and bitterness. Outing one’s personality quirks or weaknesses to another person goes opposite to OC tendencies of masking inner feelings—therefore, the importance of this when treating OC cannot be overstated. Plus, since expressing vulnerability to others functions to enhance intimacy and desires to affiliate, the practice of outing oneself when used in other areas of life can become a powerful means for OC clients to rejoin the tribe. Practicing self-enquiry is particularly useful whenever we find ourselves strongly rejecting, defending against, or agreeing with feedback that we find challenging or unexpected. Self-enquiry begins by asking: “Is there something to learn here?” Examples of self-enquiry questions include:

✓

Is it possible that my bodily tension means that I am not fully open to the feedback? If yes or possible, then: What am I avoiding? Is there something here to learn?

✓

Do I find myself wanting to automatically explain, defend, or discount the other person’s feedback or what is happening? If yes or maybe, then: Is this a sign that I may not be truly open?

✓

Do I believe that further self-examination is unnecessary because I have already worked out the problem, know the answer, or have done the necessary self-work about the issue being discussed? If yes or maybe, then: Is it possible that I am not willing to truly examine my personal responses?

The second new “how” skill in RO-DBT mindfulness is “Awareness of Unhelpful Judgments”. Our brains are hard-wired to evaluate the extent we “like or dislike” what is happening to us each and every moment. Thus, from an RO-DBT perspective we are always judging and our perceptual biases influence our relationships and how we socially-signal. RO-DBT encourages clients to use self-enquiry to learn how judgments impact relationships and social-signaling. For example, by asking:

✓

When I am self-critical or self-judgmental, how do I behave around others? For example, do I hide my face, avoid eye contact, slump my shoulders, and/or lower my head? Do I speak with a lower volume or slower pace? Or do I tell others that I am overwhelmed and/or unable to cope?

✓

How does my self-critical social-signaling impact others? What might my self-judgmental social-signals tell me about my desires or aspirations? What am I trying to communicate when I behave in this way?

RO-DBT Skills Generalization: Building Bridges to Enhance Social-Connectedness

In standard DBT, the function of enhancing skills generalization is most frequently accomplished via the use of telephone skills coaching by the individual therapist (see

Linehan, 1993a). In general, OC clients are less likely to utilize this mode. As one client characterized by over-control explained “I just don’t do crisis.” In our current RO-DBT multi-center RCT (project REFRAMED) the majority of ‘skills coaching’ involves clients learning to celebrate success by text-messaging their therapist when the use of an RO-skill ‘worked’ or using text-messaging to practice ‘outing-themselves’ when they experience new insight or learning following a practice of self-enquiry. In addition, RO-DBT encourages therapists to invite families, partners, or caregivers to participate in treatment. The RO-DBT treatment manual (

T.R. Lynch, in press) includes RO-couple therapy and RO-multi-family treatment protocols. Treatment strategies with families, couples, and other important members of a client’s social network typically involve: 1) educating the family/partner/caregiver about the RO-DBT neurobiosocial theory and linking this to the treatment strategies being used with the client; 2) explicit training in core RO-DBT skills to facilitate skills generalization; 3) modeling and encouraging dialectical thinking, e.g., demonstrating that there can be more than one way of thinking about something; and 4) encouraging the family/partner/caregiver to embrace a spirit of radical openness and “self-inquiry” when problems or challenges arise.

RO-DBT Consultation and Supervision: Practicing Radical Openness Ourselves

Therapists using RO-DBT ideally build into their treatment program a means to support therapists to practice radical openness themselves and support them in effectively delivering the treatment. This most often translates into a weekly therapist consultation team meeting. In RO-DBT a consultation team meeting is highly recommended, but not required. The rationale for making the consultation team optional is partly influenced by the less severe crisis generating behavior seen among clients characterized by over-control, as well as practical, since the majority of therapists treating over-controlled problems do not traditionally work in teams. Therapists without teams are encouraged to find a means to re-create the function an RO-consultation team (e.g., virtual teams; supervision). Consultation team meetings serve several important functions, including reducing therapist burnout, providing support for therapists, improving phenomenological empathy for clients, and providing treatment planning guidance. Plus, a major assumption in RO-DBT is that to help clients learn to be more open, flexible, and socially connected, therapists must practice the same skills in order to be able to model them to their clients. Thus, the consultation team in RO-DBT is considered an important means by which therapists can “practice what they preach” to their clients.