Patients’ Self-Presentational Tactics as Predictors of the Early Therapeutic Alliance

The therapeutic alliance is one of the most important predictors for therapy outcome (

Horvath & Symonds, 1991;

Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000). The quality of the alliance at the beginning of therapy seems to be of particular importance as it predicts the further development of the alliance and outcome (for an overview see

Horvath, 2001). The quality of the alliance is plausibly a product of other factors; however, only few studies have investigated predictors of the therapeutic alliance. Extant research shows that therapist variables, including good communication skills, empathy, openness, and collaboration, are related to a good alliance, while client variables, such as more severe problems, personality disorders, and insecure attachment styles, are related to a poor alliance (

Horvath, 2001).

Social Influence and the Therapeutic Alliance

From a social psychological perspective, the therapeutic alliance can be understood as a process of social influence. Strong and Claiborn (1982) claimed a constant mutual influence exists between therapist and patient. While numerous studies have investigated the ways in which therapists use these methods to influence patients to cope with problems (e.g.,

Abraham & Michie, 2008;

Frank, 1971;

Heppner & Claiborn, 1989), only a few have focused on how patients influence their therapists (

Friedlander & Schwartz, 1985;

Schütz, Richter, Köhler, & Schiepek, 1997). Friedlander and Schwartz elaborated on an impression management perspective in the therapeutic process (1985). They argued that as a novel social situation, the therapeutic alliance would render the interactional peculiarities of the patient salient and induce him or her to think about how best to present himself or herself to the therapist. These tendencies are further increased because psychotherapy is an image-threatening situation for the patient (

Baumeister, 1982). Because of the asymmetrical relationship between patient and therapist, the patient not only wants to be perceived by the therapist as friendly, disclosing, attractive, and motivated (

Carkhuff & Alexik, 1967;

Goldstein & Simonson, 1971;

Heller, Meyers, & Kline, 1963), but also show that he takes responsibility for problematic behavior or failure (

Batson, 1975;

Sherrard & Batson, 1979).

Self-Presentational Tactics

Self-presentational (or impression management) tactics are defined as the behaviors used to create, modify, or maintain impressions. The motivation to use these behaviors is believed to be strongest in the first contact, and people are particularly motivated to manage the impressions they make on strangers (

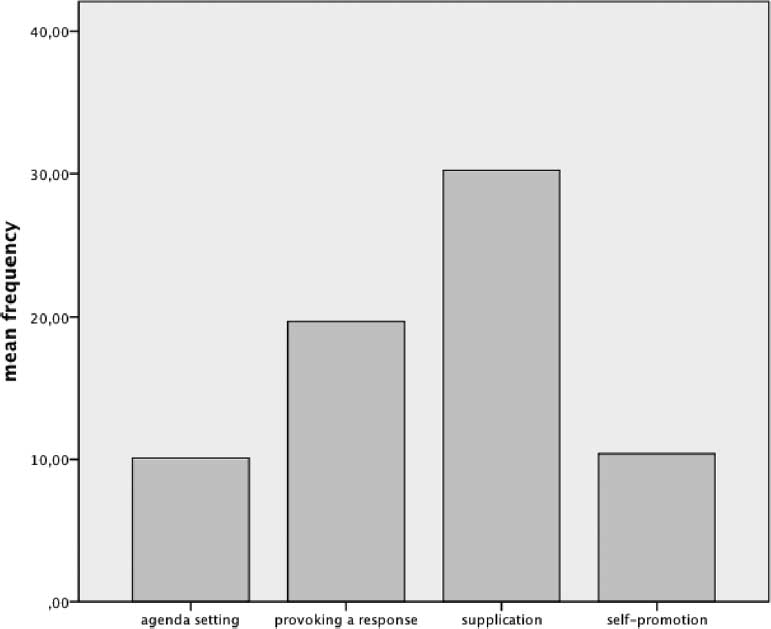

Leary et al., 1994). Hence, we investigated self-presentational tactics of patients during the intake interview where patients are meeting their therapist for the first time, and we found that patients use such tactics in roughly 30% of their utterances (

Frühauf, Figlioli, Oehler, & Caspar, 2015). Given that researchers have indicated a constant influence between therapist and patient, and that first impressions are critical in the development of a relationship, it seems plausible that patients’ attempts to influence their therapists’ perceptions of them have an effect on the therapeutic alliance. The aim of the present study was thus to investigate if the self-presentational tactics of

Agenda setting, Provoking a response from the therapist, Self-promotion, and Supplication (see

Table 1) can predict the early therapeutic alliance.

Agenda Setting

Agenda setting is a means for patients to present themselves as motivated and cooperative. In medical environments patients are trained to use

Agenda setting as a self-management skill (

Frankel, Salyers, Bonfils, Oles, & Matthias, 2013). Researchers have found that the use of

Agenda setting was associated with better treatment outcomes, reduced treatment costs (

Bodenheimer, Lorig, Holman, & Grumbach, 2002), higher satisfaction of patient (

Michie, Miles, & Weinman, 2003) and physician (

Beckman, Markakis, Suchman, & Frankel, 1994;

Roter, Hall, Blanch-Hartigan, Larson, & Frankel, 2011), less premature acceptance of hypotheses by the physician (

Beckman et al., 1994), and higher treatment adherence (

Michie et al., 2003). It is possible that

Agenda setting will produce similar outcomes with psychotherapy patients where they may have a clearer idea about what they want to achieve in therapy and practitioners in turn would appreciate this. Conversely, an overly concrete conception about what should be accomplished in a therapy could render patients less open towards the therapists’ suggestions. Nevertheless, results of the aforementioned studies seem to provide more support for

Agenda setting to have a positive effect. Therefore we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Agenda setting is positively associated with the early therapeutic alliance.

Provoking a Response From The Therapist

Similar to Agenda setting, the tactic of

Provoking a response from the therapist is indicative of an active communication between patient and therapist. Studies in medical settings have found that patients who asked more questions had better outcomes as measured by level of anxiety (

Thompson, Nanni, & Schwankovsky, 1990), role limitations, physical limitations (

Greenfield, Kaplan, Ware Jr, Yano, & Frank, 1988;

Greenfield, Kaplan, & Ware, 1985;

Kaplan, Greenfield, & Ware Jr, 1989), functional status (

Greenfield et al., 1985;

Kaplan et al., 1989), and physiological status (

Greenfield et al., 1988;

Kaplan et al., 1989).

Asking questions is a means for patients to actively participate in the treatment, which should, similarly to Agenda setting, be welcomed by practitioners. We therefore hypothesize that it is positively associated with the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy.

Hypothesis 2: Provoking a response from the therapist is positively associated with the early therapeutic alliance.

Self-Promotion

The tactic of

Self-promotion has been investigated most often in organizational settings. Barrick, Shaffer, and DeGrassi (2009) found that people who used

Self-promotion in job interviews were evaluated more positively by interviewers than those who did not. Because people use this tactic to highlight their competencies (

Jones & Pittman, 1982), it makes sense for it to have a positive impact on the person’s evaluation. In psychotherapy, the use of

Self-promotion signals the patients’ awareness of their resources and thereby draws the therapists’ attention to these, so that they can be used for therapy. Being focused on one’s resources activates the approach mode (

Gassmann & Grawe, 2006), which makes patients more open for therapeutic interventions. The use of this tactic should thus be positively associated with the early alliance.

Hypothesis 3: Self-promotion is positively associated with the early therapeutic alliance.

Supplication

The burden of suffering is generally viewed as a prerequisite for therapy motivation.

Klauer, Maibaum and Schneider (2007) found that a high burden of suffering at the beginning of therapy was associated with fewer dropouts. The explicit expression of suffering,

Supplication, is not necessarily perceived as positive for the therapeutic alliance.

Caspar (2007) sees

Supplication as a problematic behavior, possibly driven by motives that are in the way of straightforward change unless one deals with them appropriately. He recommends therapists not respond to it on the behavioral level to avoid reinforcement. Instead, he advises therapists to try to comprehend the motives behind it, trace them back to unproblematic higher motives, and behave complementarily to these. These goals are associated with a prescriptive concept referred to as motive oriented therapeutic relationship, which has been shown experimentally to improve therapies (e.g.

Berthoud, Kramer, Roten, Despland, & Caspar, 2013). Establishing such a relationship in the intake interview seems to be challenging for therapists. The intake interview is a situation in which the therapist and patient do not know each other, and yet, the patient is expected to talk about his/her problems. Finding a balance between responding empathically to patients’ reports of difficulties, but at the same time avoiding reinforcement of

Supplication might be difficult for the therapist to achieve. Furthermore, a large amount of

Supplication might indicate avoidance in addressing problems (

Sachse, Fasbender, & Sachse, 2011), which is a suboptimal basis for psychotherapy in general and also for the therapeutic alliance specifically. We, therefore, suggest:

Hypothesis 4: Supplication is negatively related to the therapeutic alliance.

Rating of the Therapeutic Alliance

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the therapeutic alliance. The mean values for the therapist’s perspective show an ascending trend from sessions one to three. The same holds for the patient’s perspective, although there is a slight decline in session two. Furthermore, the means of the therapeutic alliance as judged by the therapist are higher than those as judged by the patient.

Table 3 shows the association between the ratings of the therapeutic alliance from the two perspectives. There was no significant correlation between the therapists’ and the patients’ ratings.

Hypothesis 1: Agenda Setting and the Therapeutic Alliance

Correlation coefficients and

p-values for the associations between the tactics and the therapeutic alliance can be found in

Table 4. There was a significant positive and moderate association between the tactic

Agenda setting and the therapeutic alliance, as judged by the therapist in session 1 and3(

r =.421,

p = .002 and

r=.298,

p=.026, respectively), but not for the judgements in session 2 (

r=–.001,

p=.497). There was a significant negative and moderate association between

Agenda setting and the therapeutic alliance as judged by the patient for session 1 and session 2 (

r=–.392,

p=.007 and

r=–.268,

p=.043, respectively). For session 3 there was also a negative and small to moderate association, which was moderately significant (

r=–.238,

p=.056). Hypothesis 1 can thus be accepted for the association between

Agenda setting and the therapeutic alliance as judged by the therapist. However, the association between

Agenda setting and the therapeutic alliance from the patient’s perspective was in the opposite direction from the predicted.

Hypothesis 2: Provoking a Response from the Therapist and the Therapeutic Alliance

No significant correlations were found between the tactic Provoking a response from the therapist and the therapetic alliance as judged by the therapist (r=–.022, p=.443; r=–.046, p=.381 and r=–.002, p=.494, respectively) and by the patient (r=.004, p=.491; r=–.163, p=.151 and r=–.059, p=.347, respectively). Therefore, hypothesis 2 is rejected.

Hypothesis 3: Self-Promotion and the Therapeutic Alliance

The association between the tactic Self-promotion and the therapeutic alliance as judged by the therapist was significantly positive and moderate in all three sessions (r=.462, p=.001; r=.364, p=.006; and r=.296, p=.027, respectively), whereas the strength of the association decreased in the course of the sessions. The association between Self-promotion and the therapeutic alliance as judged by the patient was significantly positive and small to moderate only in session 2 (r=.274, p=.040), but there were no significant associations in session 1 (r=.107, p=.262) and session 3 (r=-.081, p=.296). Hypothesis 3 can thus be accepted for the therapists’ perspective and partly for the patient’s perspective.

Hypothesis 4: Supplication and the Therapeutic Alliance

The associations between the tactic Supplication and the therapeutic alliance as judged by the therapist were negative and small to moderate in all sessions, with significant correlations in sessions 2 and 3 (r=–.287, p=.026 and r=–.411, p=.003, respectively), but not in session 1 (r=–.186, p=.110). There was no association between Supplication and the therapeutic alliance as judged by the patient (r=.151, p=.183; r=.018, p=.455 and r=.144, p=.169, respectively). Hypothesis 4 can thus be accepted regarding the relation between Supplication and the therapeutic alliance as judged by the therapist, but not for the therapeutic alliance as judged by the patient.

Discussion

This study examined the association between patients’ self-presentational tactics and the early therapeutic alliance. First, it should be noted that the therapists’ and the patients’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance in the first three sessions were unrelated. This finding is in line with other studies that also found therapists and patients viewed the alliance differently (e.g.,

Bachelor & Salamé, 2000;

Cecero, Fenton, Frankforter, Nich, & Carroll, 2001;

Fitzpatrick, Iwakabe, & Stalikas, 2005;

Hilsenroth, Peters, & Ackerman, 2004). Other studies, however, have found correlations between therapists’ and patients’ alliance ratings (

Casey, Oei, & Newcombe, 2005;

Kivlighan & Shaughnessy, 1995;

Mallinckrodt & Nelson, 1991). Unlike most other studies (

Shick Tryon, Collins Blackwell, & Felleman Hammel, 2007), therapists in our sample gave higher ratings for the therapeutic alliance than patients. A possible explanation is that the clinic of Bern puts a strong emphasis on the therapeutic alliance. The therapists might thus feel quite comfortable about their ability to build a good alliance, which is reflected in the higher ratings as compared to the patients’ ratings. Another reason could be the sample. A meta-analysis found that the divergence between patients’ and therapists’ ratings was higher when patients had severe disturbances (i.e. patients with severe substance abuse disorders evaluated the alliance more favorably). Patients in our sample were outpatients, who mostly pay for therapy themselves, which might make them more critical in the evaluation of the therapist.

We found that three out of four self-presentational tactics were correlated with ratings of the early therapeutic alliance.

Agenda Setting

As predicted, there was a positive association between this tactic and the therapeutic alliance, as judged by the therapist. Therapists probably appreciate when patients participate actively in therapy by introducing their own ideals and goals. There was, however, a negative correlation between the patients’ ratings of the alliance and the use of Agenda setting, meaning that patients who judged the therapeutic alliance more negatively demonstrated this tactic to a greater extent. A possible reason for a frequent use of this tactic is these patients’ need for autonomy or control. Negatively put, patients who do not trust their therapists or doubt their ability to help them may feel the need to take matters into their own hands. One way of doing so is setting their goals for the therapy. Another possibility is that patients who come to therapy with already defined goals are more demanding and critical. These high standards may be reflected in their more critical evaluation of the therapeutic alliance, compared to other patients.

Provoking a Response from the Therapist

This tactic was not associated with the therapeutic alliance as judged by both therapist and client. The simplest explanation is that this tactic is not relevant for the therapeutic alliance. This would, however, be contradictory to the findings of studies from medical setting. Some of these studies have found that patients who asked more questions had better outcomes (

Greenfield et al., 1988,

1985;

Kaplan et al., 1989;

Thompson et al., 1990). It is possible that these studies measured something different from what we did. Specifically, we included organizational and technical questions, whereas in the medical studies patients were explicitly instructed to ask questions pertaining to their medical condition. Another possibility is that the intake interview with a physician is fundamentally different from a psychotherapy intake interview. The traditional role of a patient in medical settings is a passive one-patients are not expected to get very involved. Asking more questions can thus be expected to lead to a better exchange between physician and patient. In psychotherapy, on the other hand, an active participation of the patient is understood and necessary. The tactic

Provoking a response from the therapist might hence not be an appropriate operationalization for an active exchange between the therapist and the patient.

Self-Promotion

As predicted, this tactic was positively associated with the therapeutic alliance from the therapists’ perspective and partly also from the patients’ perspective. These results suggest that patients who use the tactic

Self-promotion in the intake interview might build up a better therapeutic alliance. Patients who are capable of

Self-promotion likely have more psychological resources and more confidence that they can benefit from psychotherapy. Being aware of their resources activates the approach mode, in which one is oriented towards positive goals. Being in the approach mode is beneficial for the development of the therapeutic alliance (

Grawe, 2007). Additionally, it is conceivable that

Self-promotion helps the therapist identify the patient’s resources better, and the therapist can more easily reinforce them. This would result in a further activation of the approach mode, and set up a positive feedback effect. It is likely that these patients have a better treatment outcome than patients who are less aware of their resources. The non-consistent positive association between

Self-promotion and the therapeutic alliance as judged by the patient could indicate an unstable activation of the approach mode: It is likely that patients who use

Self-promotion often are aware of their resources, but not consistently so.

Supplication

As predicted, this tactic was negatively related to the therapeutic alliance, but only from the therapists’ perspective. Several reasons might explain the therapists’ negative evaluation of the alliance with these patients. First, it might be difficult for therapists at this early stage of therapy to identify the unproblematic higher motives of these patients that underlie the

Supplication on the behavioral level, and respond complementary to them as the motive oriented therapeutic alliance approach suggests. Furthermore, excessive use of

Supplication might indicate an avoidance of approaching the problem (

Sachse et al., 2011). It is evident that therapists respond less positively to patients who do not seem to be motivated to change.

Supplication might also point to relationship issues. For example, the excessive report of difficulties might play an instrumental role in these patients’ lives to fulfill goals like getting attention or not having to take responsibilities or fulfill a duty. It is probable that such behavioral patterns evoke negative reactions like anger or helplessness in the therapist, like they do in the other relationships of the patient.

Taken together, patients’ self-presentational behavior can be regarded as a promising predictor for the early therapeutic alliance: We found moderate associations between the tactics Agenda setting, Self-promotion, and Supplication and the therapeutic alliance.

Practical Implications

Because of the correlational nature of our findings, it is premature to conclude that patients’ self-presentations are causal factors in the development of the therapeutic alliance. However, the consistent and moderate associations suggest that they play a role in it, and might be worth the therapists’ attention.

Generally, our findings provide hints about with which patients it may easier to build a therapeutic alliance (namely, those who use the tactics Agenda setting and Self-promotion more often than Supplication). Also, the findings point at potentially important patient needs (e.g., the need for affirmation with patients who use Self-promotion a lot or the need for orientation and control for those who use Agenda setting), which can be explored more thoroughly in the interview. Taking these needs into account is essential for establishing a motive oriented therapeutic relationship. Furthermore, our findings indicate which psychological reactions certain patient behaviors may evoke in the therapists: potentially rather positive ones in the case of Agenda setting and Self-promotion and rather negative ones in the case of Supplication. Knowing this may make the therapist more aware of possible spontaneous and unintended reactions to the more difficult patient behaviors.

It can generally be recommended that therapists should reinforce the tactic

Agenda setting. First, we found this tactic to be positively associated with the therapeutic alliance from the therapists’ perspective. It seems plausible that by setting their own therapy goals patients contribute actively to a positive therapeutic alliance and process. Second, self-set goals are related to higher self-efficacy (

Schunk, 1990), which in turn is an important predictor for treatment effectiveness (

Greenberg, Constantino, & Bruce, 2006). Nevertheless, it should be remembered that this tactic was negatively associated with the therapeutic alliance from the patients’ perspective. If our interpretation holds that patients take matters into their own hands because they lack trust in their therapist, than therapists should first focus on building up trust and show the patients that they support them in developing therapy goals.

Even though we found the tactic of

Provoking a response from the therapist to be unrelated to the therapeutic alliance, it may subsume a beneficial behavior for the therapeutic process. Asking questions is certainly a means for patient to actively participate in therapy, which is generally associated with better therapy outcome (

Stewart, 1995). Thus, therapists should encourage patients to ask questions.

Emphasizing strengths – Self-promotion – is a behavior that therapists should definitely reinforce with their patients. As outlined above, it can provide a valuable source of information about where the patients’ strengths lie. Affirming them is an excellent means for therapists to build up relational credit.

According to

Caspar (2007) and the present findings,

Supplication should not be reinforced if it appears to be determined more by relationship than problem issues. Therapists should, in the sense of a motive oriented therapeutic relationship, try to identify the motives behind the Supplication and try to act complementary to them.

This study added knowledge to the still nascent field of research in predictors of the therapeutic alliance. This study’s findings increase our understanding of factors that may be important in the development of the early therapeutic alliance. If patients’ self-presentational behaviors affect the alliance in a positive or negative way, therapists must take such behaviors into account and react constructively.