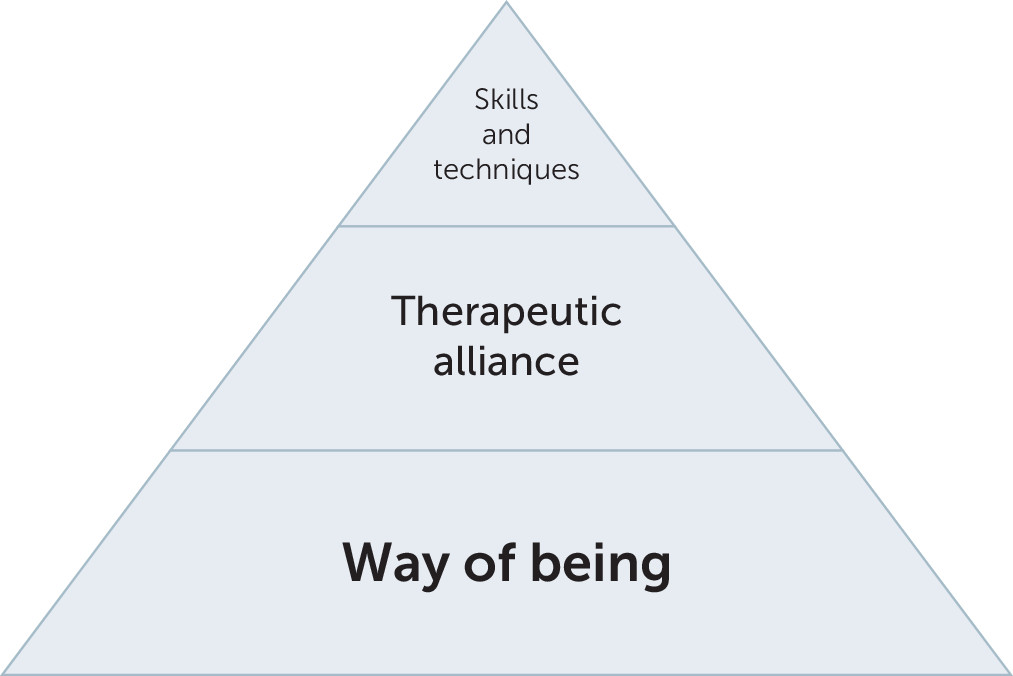

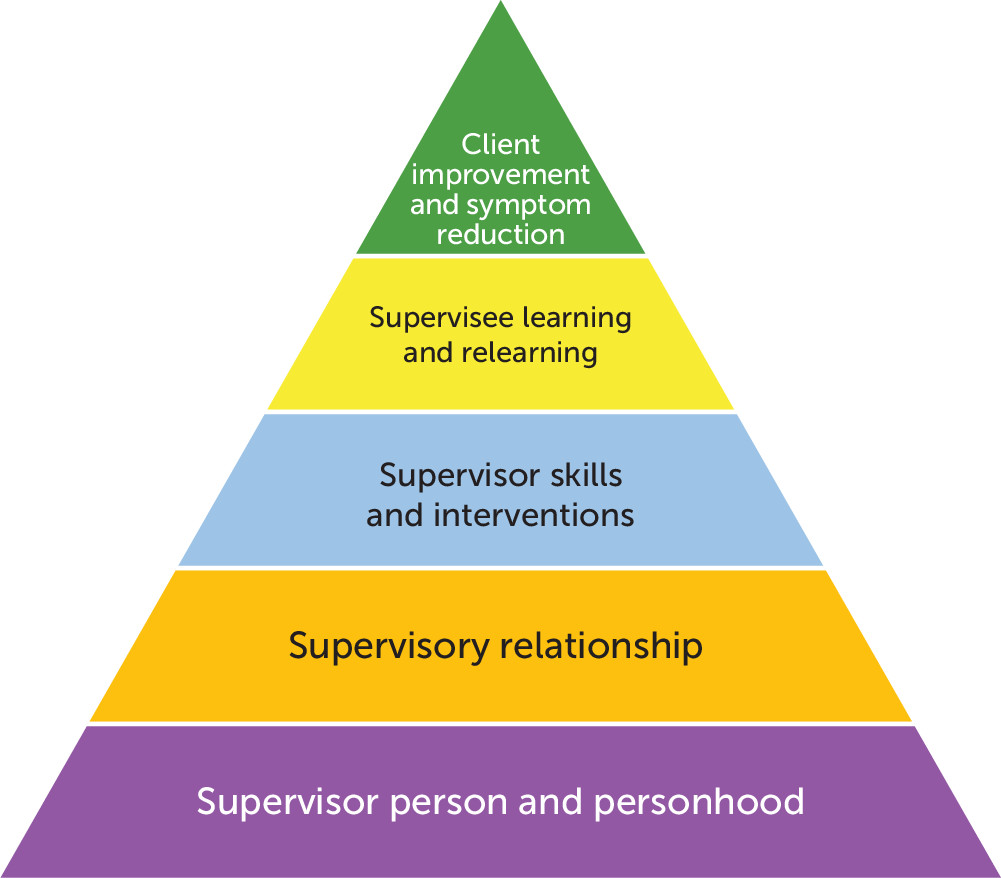

Although Fife and colleagues (

6) labeled the bottom block of their pyramid as

way of being, I have chosen to relabel that block as the supervisor’s

person and personhood. Although a host of variables may be involved in the supervisor’s person and personhood, emphasis is given to two crucial considerations: way of being and supervisor presence.

Supervisor presence.

Presence has increasingly emerged as an eminently important common factor in psychotherapy (

81–

85). Reasoning by analogy (

14), I contend that presence is an equally and eminently important common factor for the effective practice of psychotherapy supervision. Presence is a prerequisite for supervisor-supervisee relationship development; it is the ground—the hub—upon which alliance and real relationship are built (cf.

84,

85). Supervisor presence, defined as the state of having one’s whole self in the supervisor-supervisee encounter, being completely in the moment on a host of levels (

82), involves at least four critical features: being in touch with one’s own healthy and integrated self, being receptive and open to and immersed in the present, allowing in-the-moment expansion of one’s awareness, and having full intention and being fully functioning so as to be of service to one’s supervisees and their clients (cf.

82,

84). It is the supervisor’s “being here,” “being now,” “being open,” and “being with and for” during supervision (

81), a generative mix of appreciative openness, concerted encouragement, support, and expressiveness (

85). Supervisor presence models and invites, showing by doing and ideally eliciting the supervisee’s presence in return.

Way of Being.

Perhaps Anderson (

86) captured the essence and intent of way of being best. It “conveys to the other that they are valued as a unique human and not as a category of people; that they have something worthy of saying and hearing; that you meet them without prior judgment.” It is foremost an open, genuine

attitude of caring, passion, and compassion toward our supervisees as learners and the vulnerabilities that they experience in the learning situation. That attitude is nicely put on display by Lewis (

87), in this passage that I have always appreciated for its sensitivity and humanity: “The successful supervisor will be able to allay the anxiety of the supervisee. . . . Here you are not anonymous or abstinent. Here you are a real person. Here you show your warmth and openness and acceptance. Here you praise, support, encourage, and advise. Here you show your empathy to the vulnerability of a learner. Here you share your own experiences, your own mistakes. Here you share your own doubts and anxieties as a learner.”

Supervisors value the person and personhood of their supervisees, privilege and prioritize their supervisees’ needs, and are fully committed to the constructive instigation of therapist development.

Fife and colleagues (

6) contended that the desired therapeutic way of being is best captured by means of an I-Thou as opposed to I-It stance (

88). The same could be said for psychotherapy supervision. Whereas I-It views the other as object not subject, where some

one becomes some

thing (

6), the I-Thou view is antithetical in every way, forever guided by such cardinal watchwords as respect, engagement, appreciation, valuing, prizing, and generativity. Supervisors ideally hold an I-Thou attitude about supervision and bring that attitude with them to each session, the foundational building block for supervisor-supervisee connection.

The supervisor’s I-Thou stance reflects that most fundamental conviction: how you are is as important as what you do (

89). I-Thou is also well reflected in supervisor enactment of such guiding and abiding values as eminent valuation, abiding fidelity, and relational privilege (

90).

Eminent valuation refers to the supervisor’s valuing supervision supremely, viewing it as preeminently crucial for supervisee learning, and consistently putting that view into practice during supervision.

Abiding fidelity refers to the supervisor’s being studiously loyal and committed to supervision as a field of practice and his or her own continuing development as a supervision practitioner.

Relational privilege refers to a supervisor’s granting high privilege to the supervisor-supervisee relationship and treating it accordingly, regarding the jointly forged relationship as being the crucial mediator that ultimately makes the totality of supervision work. When these values and principles of action are put in place, the supervisor’s way of being is apt to be increasingly mutative and educationally liberating.

Although I-Thou discussions are most apt to be found in humanistic-existential supervision writings (e.g.,

49,

91), an I-Thou (way of being) stance is not model dependent and is by no means the exclusive property of any one perspective (cf.

6). It is a way of wanting to be with an other that prizes and prioritizes the supervisee and his or her learning. Evidence for that foundational attitude of humanity and humaneness, caring and concern, investment and engagement, and passion and compassion can readily be found across all supervisory perspectives, no matter how disparate (e.g.,

23,

24,

62,

64,

74,

76,

92). Way of being is what we as supervisors bring with us to supervision, and, ideally, we do so constructively and in at least “good enough” fashion each time.

Unfortunately, that is not always the case. Research suggests that some supervisees experience either inadequate or harmful supervision or both. In two recent seminal studies involving more than 600 respondents from the United States and Republic of Ireland, Ellis and colleagues (

93,

94) found that virtually 100% of participating supervisees reported experiencing inadequate supervision at some point (for example, when the supervisor “does not listen” or is “not committed”); about 50% reported having experienced harmful supervision (for example, “had sexual relationship” with supervisor). Whatever might be contributing to such outcomes, it does not seem a stretch to surmise that when such troubling behaviors occur, the supervisor’s way of being has been compromised (or perhaps was never in place) and is not serving as supervision’s guide.