Externalizing behaviors are common in a wide range of child mental health problems. Oppositional defiant disorder is the leading reason for referral to youth mental health services, with a lifetime prevalence of 10.2% (

1). The

DSM-5 (

2) describes the disorder as a recurrent pattern of developmentally inappropriate levels of negativistic, defiant, disobedient, and hostile behavior toward authority figures. Children with disruptive behavior disorders, such as oppositional defiant disorder, are more likely to have impaired academic progress, early substance use problems, and higher rates of adult incarceration (

3,

4). A significant proportion of children with acute externalizing behaviors have poor longitudinal outcomes in terms of psychopathology and functional ability (

1). The disorder also is a strong predictor of generalized anxiety disorder, panic, and depression in adulthood (

5). Although a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder increases a child’s risk for poorer outcomes across the lifespan, the disorder is highly variable in its presentation and developmental trajectory.

Current Treatment Approaches

Psychosocial treatments are the preferred first-line treatment for disruptive behavior problems (

6). Current evidence-based approaches for elementary school–age children with oppositional defiant disorder include behavioral parent training (

7–

9), family skills training approaches (

10,

11), and the collaborative and proactive solutions intervention (

12). There are two components to all behavioral parent training approaches: working to improve the parent-child relationship and providing parents with more effective behavior management strategies, such as positive attending, contingent attention, reinforcement, and the use of time-out procedures (

13). These interventions help parents define and monitor their child’s behavior, improve their parenting practices, and apply consistent and effective discipline to encourage prosocial behaviors. Family skills training builds on traditional behavioral interventions by offering children and parents their own skills groups and providing structured opportunities for the family to practice together (

11). Collaborative and proactive solutions is a cognitive-behavioral model that emphasizes helping adults and children to develop skills to collaboratively resolve issues of disagreement (

14).

The aforementioned treatment approaches have demonstrated efficacy with modest effect sizes across multiple studies. However, child psychotherapy interventions are limited by the elevated attrition rates among vulnerable populations, because of factors such as low socioeconomic status, ethnic minority status, parental functioning, maternal stress, low parental motivation, and child symptom severity (

15–

18). Poor treatment compliance and outcome also are attributable to the fact that parent-focused models of treatment contradict parents’ beliefs that the cause of the problem resides within the child (

19–

21). Effectiveness of these programs is dependent on parental engagement in the treatment (

22), and because of the considerable time commitment required by such programs, participation may not be feasible for parents facing high levels of stress (

16). Nearly one-third of treated children do not benefit from traditional behavioral interventions (

17,

18), and positive effects have been shown to decline posttreatment among disadvantaged families (

23). Finally, parent training modalities are relatively expensive psychotherapy interventions that, as a result, are not always widely available in community care settings (

24).

It has also been argued that none of the cognitive and behavioral interventions described above adequately address implicit emotion regulation (

25–

27). Previous research has demonstrated the importance of addressing the affective and emotion regulation components of oppositional defiant disorder (

28–

31). In contrast to the

DSM-5 criteria for the disorder, which focus on a set of behaviors, it appears that oppositional defiant disorder is best conceptualized as a disorder of emotion regulation rather than simply a disorder of behavioral dysregulation (

26,

29,

30,

32). Negative emotionality, coupled with deficits in self-regulation, have been identified as primary precursors to behavioral difficulties such as those evident in oppositional defiant disorder (

33). Given these findings, there is a need for treatments that are cost-effective, encourage treatment compliance, and address the core implicit emotion regulation deficits that are evident in the disorder.

Regulation-Focused Psychotherapy for Children (RFP-C)

Regulation-focused psychotherapy for children (RFP-C) (

34) is a manualized, time-limited, psychodynamic treatment for children with externalizing behaviors that aims to activate more adaptive forms of implicit emotion regulation. The RFP-C treatment approach, along with many clinical examples, are described in the manual and several associated publications (

25,

26,

34–

37). The intervention consists of 16 individual play therapy sessions with the child and four parent meetings, delivered over the course of 10 weeks. RFP-C conceptualizes disruptive symptoms as maladaptive attempts to regulate emotions. When certain emotions are too difficult for children to consciously experience or verbalize, they involuntarily rely on aggressive, disruptive behaviors to hide from these painful emotions and remove them from their awareness (

26,

35). In essence, for these children, it is easier to get mad (e.g., act out) than it is to feel sadness, guilt, loss, or shame. Disruptive behaviors divert both the child’s and the caregivers’ attention away from the underlying and painful affect. These psychological processes are similar to impaired implicit emotion regulation capacities (

26,

38). The term

emotion regulation suggests internal adjustments and compromises that are made in the service of emotional homeostasis; this concept contrasts with behavioral approaches that emphasize emotional restraint (

27).

Although there is a long history of psychodynamic psychotherapy being used in the treatment of disruptive behavior problems (

34,

35,

39–

42), RFP-C is the first attempt to systematize the process of addressing children’s defense mechanisms against unpleasant emotions. Throughout the course of the play therapy sessions, the clinician notices and gently identifies the child’s defensive behaviors and verbalizations when they occur. This iterative and gradual exposure to avoided, and largely unconscious, feelings improves the child’s implicit emotion regulation abilities (

25,

35,

43), thereby enabling the child to function better in his or her environment. RFP-C also includes parent meetings that encourage caregivers to develop an understanding of the meaning of the child’s behavior.

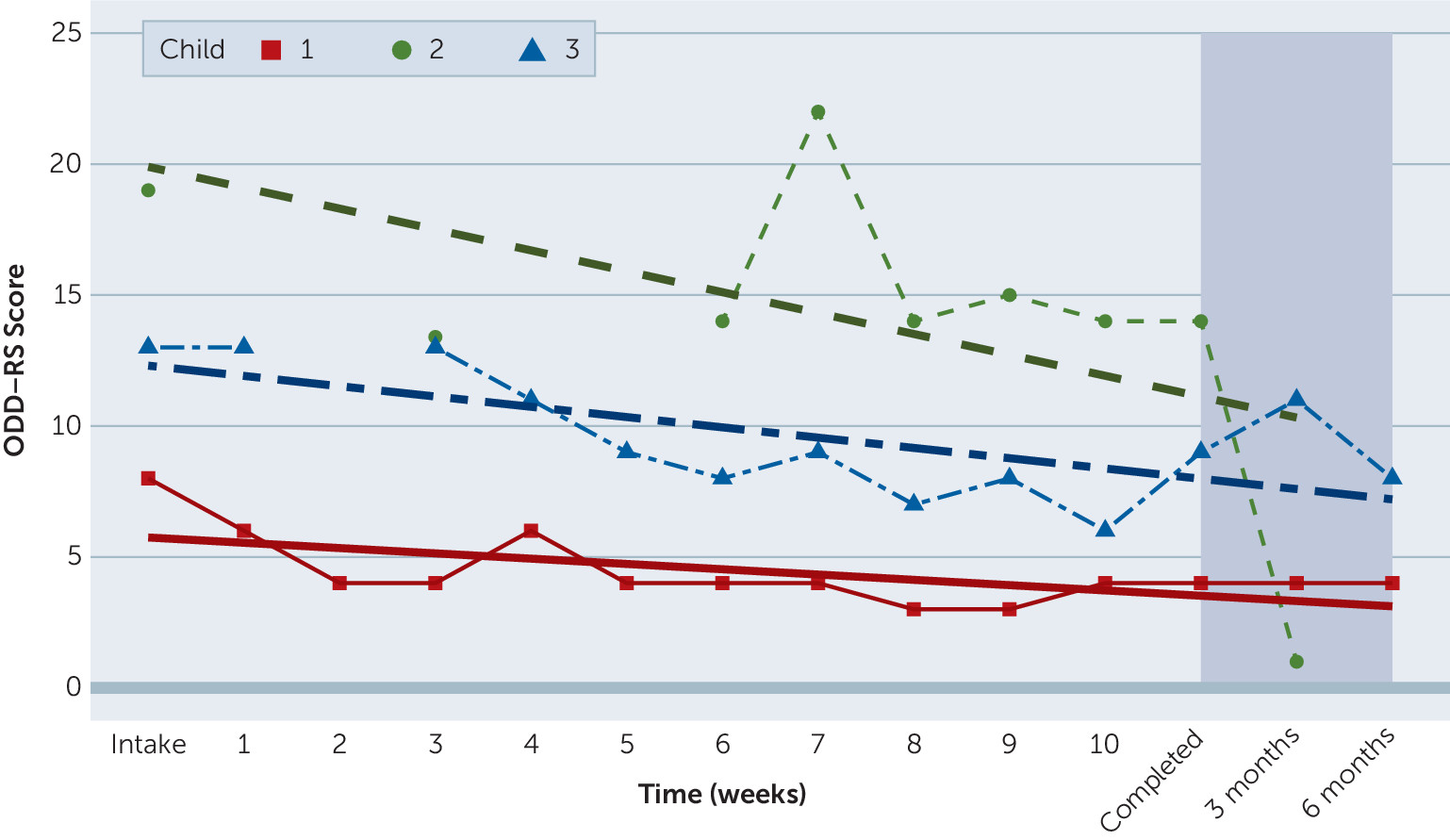

The purpose of this study was to evaluate changes in oppositional and defiant symptoms and emotion regulation among children participating in RFP-C. Three cases were selected for inclusion to obtain initial data in preparation for a larger randomized controlled trial, now underway. We hypothesized that participants’ symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder would decrease, and emotion regulation would increase, after treatment and at the three- and six-month follow-ups.

Discussion

This study is the first empirical examination of RFP-C treatment response among children with oppositional defiant disorder. Our hypothesis that children would experience a decrease in symptoms after treatment was supported. One child began with relatively fewer symptoms and experienced enough improvement to be classified as recovered. The two other children, with higher levels of oppositional and defiant behavior at the start of treatment, experienced greater improvement and were classified as improved at the end of treatment. Two of the three participants were in the recovered range at the three-month follow up.

There was also support for the hypothesis that RFP-C would be associated with improvements in the children’s abilities to manage difficult emotions. All three children demonstrated clinically significant improvements in emotion regulation. Two demonstrated significant decreases in lability and/or negativity, and one demonstrated no change in lability or negativity. Finally, parents reported a positive experience in the exit interviews, suggesting the possible utility of RFP-C among families who have traditionally had difficulty in traditional behavioral treatment. This pilot study provides preliminary support for further investigation of RFP-C. A larger-scale randomized controlled trial is now under way.

Dropout rates from psychotherapy interventions appear to have improved during the last 20 years as more tailored approaches have emerged; however, premature termination from child psychotherapy persists, with about 1 of every 3.5 clients dropping out of cognitive-behavioral treatments (

51) and even higher attrition rates among those with disruptive behavior problems (

52). It is notable that all the families in this study completed treatment and maintained attendance throughout the treatment protocol. Additionally, the intervention was cost-effective to administer ($3,333 per clinician) compared with behavioral parent training interventions ($73,000 per trained clinician) (

24). We anticipate that the average cost to deliver RFP-C can be reduced to approximately $2,500 per clinician for future studies.

This was an initial pilot study to evaluate the effectiveness of a manualized, psychodynamic intervention for children with oppositional defiant disorder. Our sample size was small, and there was no control group. A randomized controlled trial of RFP-C with a substantially larger sample size is currently under way and will add to our understanding of this treatment approach. Additionally, this study relied on parental reports of the child's symptoms; however, parents appear to be valid reporters of children’s externalizing behaviors and social functioning (

53). Future research should incorporate teacher and clinician reports of behavior. As with any pilot data, the sample size constrained our ability to evaluate for treatment moderator effects. Variables such as income and education, degree of callous-unemotional traits, and the role of adverse childhood experiences will be evaluated in future studies with sufficient sample sizes.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of oppositional defiant disorder and other disruptive behavior problems and the difficulties these disorders cause for children and their families suggest the importance of treatment protocols that can provide relief in a cost-effective manner. Given that oppositional defiant disorder presents an inordinate burden on health care expenditures (on par with asthma, epilepsy, or diabetes) (

54) and the high rates of attrition in currently available psychotherapy approaches, there is a great need for innovative methods that can be delivered by professionals with a range of clinical experience and across a variety of settings. This pilot study provides initial support for RFP-C as a clinical intervention for children with oppositional defiant disorder. Findings suggest that RFP-C is associated with significant lessening of symptoms and improvements in emotion regulation capacities. Additionally, RFP-C can be delivered as a cost-effective, brief, psychotherapy intervention that appears to help families to maintain attendance and complete the treatment.

In classrooms and families, children are often identified because of oppositional behavior that creates problems for those around them. The profound difficulties these children have managing the unpleasant emotions that they experience as intolerable are less readily apparent. Although the presenting problem is the disruption or aggression the child displays, contemporary, neuroscience-informed models suggest that these symptoms are signals of underlying impairments in emotion regulation. RFP-C works to remove roadblocks to managing difficult and unpleasant emotions, especially in children who have profound deficits in this area.

Explicit emotion regulation strategies, such as effortful distraction and cognitive reappraisal, are the primary targets of cognitive-behavioral interventions. In contrast, implicit regulatory strategies (much like defense mechanisms) are automatic, and thus outside of the child’s awareness. Yet, these strategies negatively affect children’s ability to cope with negative feelings and life stressors. In fact, a child’s capacity for implicit emotion regulation may be more important for a child’s emotional functioning than explicit skills to manage disruptive behavior (

26,

35,

55). The procedures in RFP-C are designed specifically to engage children and families who have not done well in treatments emphasizing explicit skills. The clinician’s focus on the child’s in-session behaviors (e.g., remaining experience-near) and gradually increasing awareness of the meaning and the implicit purpose of disruptive behavior (e.g., protecting the child from painful affect), allows children to build implicit emotion regulation abilities in a safe, therapeutic environment. Parent meetings in RFP-C also empower parents to adjust their expectations and understanding of the child so that the home environment can better support these children as they begin to modify the quality, intensity, and duration of their emotional response. Close attention to children’s difficulties with shame, guilt, sadness, and loss—as is the norm in RFP-C—may help facilitate greater and more lasting recovery from oppositional defiant disorder and other externalizing disorders.