Dignity Therapy

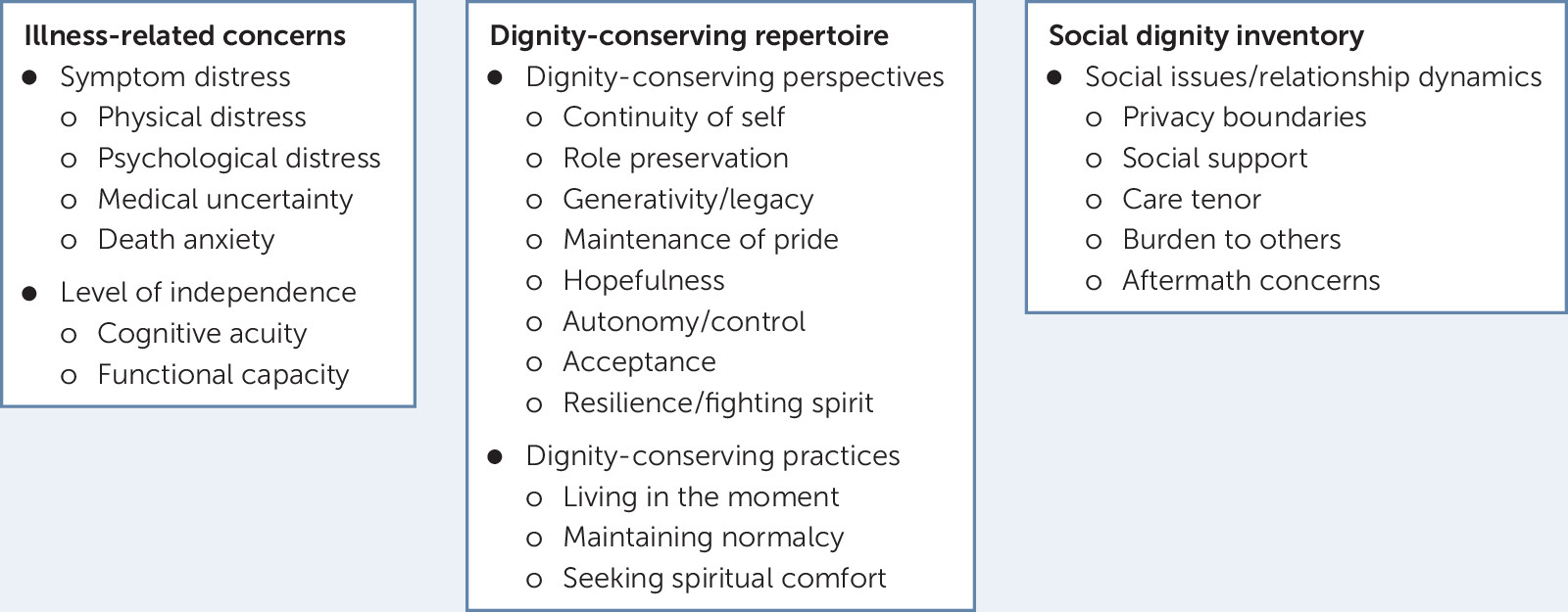

Dignity therapy is an established intervention for terminally ill populations, with demonstrated efficacy in enhancing end-of-life experience (

28–

31). This brief intervention targets sense of meaning, purpose, and dignity, and is based on the model of dignity for the terminally ill and related research (

28–

31). The therapy uses a framework involving open-ended questions delivered by a trained professional that elicit memories, hopes, wishes, life lessons, and the legacy the patient wishes to leave for loved ones (

30) (

Box 1).

Sessions are recorded and transcribed verbatim, then edited to create a narrative or generativity document for patients to bequeath to friends and family. The efficacy of dignity therapy has been evaluated in many clinical and cultural contexts (

32–

36), often through the use of the Patient Dignity Inventory (

37), a 25-item self-report measure assessing domains of symptom distress, existential distress, dependency, peace of mind, and social support. This tool has been validated in several languages (e.g., Greek, Mandarin, Spanish, Italian, German) and among patients with various illnesses, including specific cancers, noncancer terminal illness, and psychiatric illness (

38–

42). Additionally, a briefer measure called the Dignity Impact Scale has been validated for use as a clinical marker of dignity that can be used pre- and postintervention (

43).

More than 85% of patients and families have found dignity therapy helpful and have been satisfied with the intervention (

44). In the first randomized controlled trial of dignity therapy compared with supportive psychotherapy and standard palliative care (

31), those receiving dignity therapy were more likely to report that the intervention was helpful, enhanced their sense of dignity, changed how their family saw them, and that they felt it would be helpful to their families. Because baseline levels of distress were low in the trial, significant differences on symptom distress, depression, anxiety, desire for death, and suicidality did not emerge. However, trials of dignity therapy among patients with higher baseline levels of distress have demonstrated significant improvements in depression and anxiety symptoms at the end of life (

45,

46). Recent systematic reviews of dignity therapy (

47,

48) show that it is efficacious for increasing a sense of dignity. Pooled effect sizes on anxiety and depression symptoms have been nonsignificant but have favored dignity therapy over control interventions, and there is evidence that dignity therapy also has enhanced self-reported quality of life. However, heterogeneity in how quality of life has been assessed across studies makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions regarding dignity therapy’s efficacy in this area. It has been suggested that dignity or dignity-related distress should be the primary outcome assessed in examining the efficacy of dignity therapy (

43). Other studies have focused on outcomes tracking end-of-life experience, such as increased levels of positive affect, sense of life closure, gratitude, hope, life satisfaction, resilience, and self-efficacy (

49).

As research on dignity therapy has progressed, the therapy has been adapted and paired with other interventions, including the life plan intervention (

50), family life review (

36,

51,

52), and a legacy-building web portal (

53). In addition to palliative care contexts, dignity therapy has been used to successfully reduce dignity-related distress in chronic illness (

51), bone-marrow transplant (

54), major depressive disorder (

55,

56), alcohol use disorder (

57), health-related trauma (

58), and suicidality in incarcerated populations (

59).

Other Therapies Focused on Distress at the End of Life

Meaning-centered psychotherapy (MCP) is an intervention specifically targeting a sense of meaning to mitigate existential distress at the end of life. This intervention has been studied extensively in both individual and group contexts. MCP is a seven-to-eight-session manualized psychotherapy focused on developing or increasing a sense of meaning among patients with cancer. Sessions focus on understanding sources of meaning, identity, legacy, coping with limitations, creativity, and connection. Multiple randomized controlled trials (

60–

63) have shown significant improvements in overall quality of life, sense of meaning, and spiritual well-being in those who participate in MCP compared with control interventions, such as supportive psychotherapy or usual care.

Emerging evidence supports acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) as an efficacious intervention for patients with a terminal illness, particularly for the understudied and difficult-to-target symptom of anticipatory grief. In ACT, psychological distress is thought to arise from an unwillingness to engage with unpleasant thoughts, sensations, feelings, and memories (i.e., experiential avoidance). The energy required for the aforementioned avoidance prevents or limits the pursuit of valued and meaningful activities. ACT (

64) is thus a present-focused therapy that targets increased psychological flexibility through acceptance of situations over which one has little or no control. In palliative populations, acceptance is negatively associated with psychological distress (

65). In a cohort of palliative care inpatients, acceptance was the strongest predictor of anticipatory grief, with higher acceptance associated with lower anticipatory grief, above and beyond the effects of anxiety and depression (

6). Evidence from a study of patients with cancer (

66) also suggests that increased acceptance gained through ACT treatment is associated with reduced psychological distress and improved mood and quality of life. ACT also has a strong evidence base for pain management with efficacy shown among patients with cancer and chronic disease (

67,

68); however, research specific to the end of life is limited.

In addition to the aforementioned approaches, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has a solid evidence base for use among patients receiving palliative care and may be particularly helpful in managing common symptoms of depression and anxiety in addition to physical discomfort. Cognitive restructuring related to specific maladaptive anxious or depressive thoughts and behavioral management of physical (e.g., pain and dyspnea) and psychological symptoms can be helpful. Diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and clinical hypnosis can all be useful to aid in coping, self-management, and management of pain (

69). These approaches can be adapted as needed for individual patients’ physical and cognitive constraints (

70).

Use of one therapy over another, as always, requires consideration of both the presenting concern or concerns of the patient and the skill set and orientation of the therapist. Because no research has directly compared the aforementioned approaches to each other, clinicians engaging in therapy with terminally ill populations are advised to work within an empirically supported framework in which they have received adequate training.