I first met Dr. Otto F. Kernberg in 1985, when I was a clinical psychology intern at what was then known as the New York Hospital–Cornell Medical Center, Westchester Division, in White Plains. Cornell Westchester, our shorthand for the hospital, was an exciting place to train: the intellectual ether crackled with rich discussion of phenomenology and classification, psychological assessment, advances in psychopharmacology, the emerging neurosciences, and, of course, modern psychodynamic thinking. Dr. Kernberg, as the medical director, engendered an environment where rigorous clinical discourse was expected and respect for phenomenology was assumed. In short, a proper and carefully conducted mental status examination was the starting point for all discussions when it came to patient care. At the time, my clinical rotation was on an intermediate-stay inpatient psychiatric service, where patients stayed for 6 months to 1 year and where many were treatment resistant. Thus, when I was about to present an exceptionally complicated case to Dr. Kernberg at our weekly case conference and he asked me, “Do you have a mental status exam for this patient?” I was happy to reply, “Yes, I have three of them: one from 6 months ago, one from a month ago, and one from this morning.” Dr. Kernberg replied, “Excellent, now we can really get started.” This respect for phenomenology and for the passage of time has stayed with me for my entire career and, in part, inspired me to undertake the very first National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)–funded, prospective, multiwave study of personality pathology, known as the Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders (LSPD). This article explores the issue of change versus stability regarding features of clinically significant narcissistic personality disorder (NARPD) among college-age young adults over time.

Narcissism and narcissistic personality pathology have long been of interest in psychiatry, psychoanalysis, clinical psychological science, and other behavioral science vectors (e.g., personnel selection). Clearly, the reference point for inquiry into narcissistic pathology begins with Freud (

1) and his early clinical observations. However, advances in the understanding of clinically significant narcissistic disturbances stand on the shoulders of the seminal work done by both Dr. Kernberg (

2) and Heinz Kohut (

3), who approached this domain of psychopathology from distinctly different vantage points. Separate from the world of clinical psychopathology, an interest emerged in narcissism as a personality trait within the realms of academic psychology personality science and social psychology (

4). It is important to note that clinically significant narcissistic psychopathology (

5), seen as a disorder and associated with considerable impairment, is not fungible with the trait of narcissism in a normal range, which is typically assessed with self-report questionnaires in nonclinical populations (

4,

6).

Discussion of the narcissism construct, normative trait narcissism, and pathological narcissism has accelerated in recent years, and this domain has emerged as one of the most active areas of clinical science, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, and normal personality science. Indeed, numerous reviews, think pieces, and at times strident exchanges have focused on this important area (

5,

7–

12). Many of these competing views concern the meaning of commonly used normal-range assessment measures of narcissism (

13), the correspondence of normative trait narcissism with pathological narcissism constructs (

6,

10,

14), and the capability of general personality taxonomies (e.g., the five-factor taxonomy) to encompass the full range of phenotypic expressions of narcissism (

14–

16). With increased empirical research and substantive model evaluation, critical theoretical and descriptive insights for understanding narcissism have been gleaned in recent years. Such insights have included the parsing of self-esteem from normal-range narcissism (

13); the seminal delineation of grandiose and vulnerable dimensions of pathological narcissism by Pincus and others (

4,

6,

14); the importance of well-known personality constructs in describing narcissism, such as agentic extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (

11); the relevance of complex dynamic systems for understanding narcissism (

9); and the severe psychological impact of “malignant narcissism” (

17,

18), a concept pioneered by Kernberg (

2,

19,

20). Despite these advances, the literature can become murky when one group of researchers seems to be discussing normal-range narcissism (with minimal clinical impairment) from the normal personality or social psychology perspective but other researchers seem to address pathological narcissism, which focuses squarely on noteworthy impairment in social and occupational functioning, strained family life, and considerable distress (

21). These discussions will be clarified and resolved over time with the emergence and accumulation of more empirical data.

One aspect of the study of narcissism that has generated considerable interest among both researchers and the lay public concerns claims that narcissism is on the rise with successive cohorts, particularly among college-age young adults. Reports have suggested that mean scores on self-report measures of normal-range trait narcissism have increased across several successive college cohorts (i.e., possible secular changes) (

22,

23), leading some commentators to pronounce that contemporary society is in the midst of a “narcissism epidemic” (

24,

25). The notion that U.S. society is in an epidemic of narcissism has been trenchantly critiqued on grounds of both methodology and assessment. For example, the cross-cohort increases in narcissism that are at the center of this discussion were measured with the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI), an instrument that is known to have numerous shortcomings in terms of psychometrics and validity (

10,

13,

26–

29) and that is viewed as having diminished relevance for measuring clinically significant narcissistic pathology. In addition, the robustness and scientific meaning of differences in mean NPI scores at different colleges and among different cohort samples have been questioned as adequate bases for declaring an epidemic of increasing narcissism among young people (

30–

32). Finally, a recent report, although reliant on the NPI instrument, cast considerable doubt on the notion of a narcissism epidemic by using more recent data and advanced statistical analyses (

33).

Results

Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

Demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in

Table 1. As reported previously (

35,

36), the lifetime

DSM-III-R axis I diagnoses (

Table 2) of the study participants are for definite and probable disorders. Eighty-one (63%) of the 129 participants in the PPD group received an axis I diagnosis, compared with 32 (26%) of the 121 participants in the NPD group (χ

2=33.30, df=1, p<0.001). Forty-one (32%) participants in the PPD group and 21 (17%) in the NPD group reported a prior history of treatment by the third wave of assessments (wave 3) (χ

2=6.97, df=1, p<0.008). Finally, by wave 3, 16% (N=39) of the sample had been given a probable or definite diagnosis of at least one axis II PD (or PD not otherwise specified). Note that this percentage was higher than that initially reported by Lenzenweger et al. (

34) (i.e., 11%), which was based on only wave 1 assessments. This percentage was higher because additional participants beyond those who were diagnosable at wave 1 developed a PD during the study period.

Assessment Schedule Characteristics

The PD features of each of the 250 study participants were assessed three times over the 4-year period. The mean±SD ages of participants were 18.89±0.51 at wave 1, 19.83±0.54 at wave 2, and 21.70±0.56 at wave 3. The time between assessments for each participant was calculated in years by using each individual’s date of birth and exact assessment dates and was then centered on age at entry into the study for each participant (with age at entry included as a predictor at level 2). Centering the assessment intervals on age at entry and including age at entry as a predictor at level 2 accounted for each participant’s unique chronological age when he or she began the study and caused the individual level 1 intercepts to represent the true value of the wave 1 assessments as the participant’s “initial status.” Consideration of age at entry into the study is theoretically important because it helps to account for subtle differences in the developmental level of the participants.

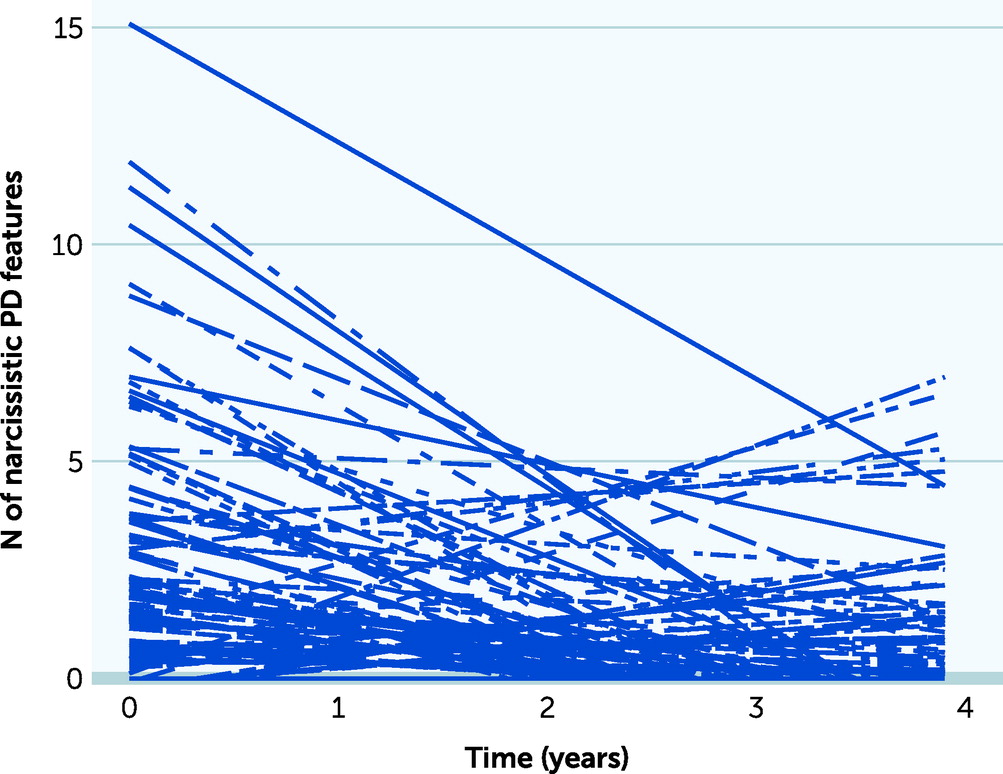

IGCs for NARPD: Visualizing Heterogeneity in Individual Growth

The heterogeneity in the individual growth trajectories for IPDE-assessed NARPD was considerable and was plotted by using an exploratory ordinary least-squares approach for NARPD features (

Figure 1). The IGC for each study participant is shown in the plot. Clearly, no single IGC characterizes all participants.

Unconditional Analyses

An unconditional growth model (i.e., containing no level 2 predictors) was fitted for the NARPD feature dimension and provided estimates of the average level and rate-of-change parameters and their natural variation across all participants upon entry into the study. The fixed effects and variance components of the unconditional growth trajectories for the NARPD feature dimension were of central interest. The estimated average elevation of the NARPD individual growth trajectories upon entry into the study (intercept) differed significantly from zero (intercept fixed effect [γ00]=1.21, p<0.001; r=0.47, representing a large effect). In addition, the intercept for the IPDE contained significant variability (σ20=4.22, p<0.001), which was then available for prediction at level 2 in subsequent conditional models.

The estimated average rate of change (slope) also differed significantly from zero for the NARPD feature dimension, indicating that considerable change over time was evident in pathological narcissism features (slope fixed effect [γ10]=−0.30, p<0.001; r=0.39, representing a large effect for slope). The important feature of this result was that it clearly indicated that NARPD features declined across the first 4 years of college. In addition, the variance component associated with rate of change (σ21=0.29, p<0.001) was statistically significant and suggestive of substantial amounts of variation in change that could be predicted in a subsequent level 2 model. Finally, the estimated slope from the unconditional growth analysis provided a pragmatic insight into the rate at which NARPD features change over time. Specifically, it was estimated that total NARPD features decreased by 0.30 NARPD units on the IPDE dimensional score with each passing year, which represents, as noted, a large effect size for slope.

Conditional Analyses

In conditional analyses, level 2 predictors were introduced to explain any between-participant variation in the individual level and rate-of-change parameters. The primary between-participant level 2 factors of interest were group membership (PPD vs. NPD), participant’s sex, and baseline values for each of the personality dimensions reflective of the primary DLM components. In addition, each participant’s age at entry into the study was included as a predictor at level 2 in order to account for interindividual variation in change associated with age (i.e., developmental level). The results of the conditional analyses are presented for the NARPD variable in

Table 3.

Table 3 includes estimates of the fixed effects and variance components associated with each level 2 predictor (study group, sex, age at entry, agentic positive emotion [agency, incentive motivation], communal positive emotion [affiliation], constraint [nonaffective constraint, neural constraint], negative emotion [anxiety], and fear), the approximate p value for testing that these effects were zero in the population, an estimate of the effect size (r), and a deviance statistic (−2 log-likelihood) for the model.

Table 3 also contains estimates of the variance components from the level 2 model, which were also tested for statistical significance.

For the IPDE NARPD feature dimension, with respect to elevation of the individual growth trajectories, statistically significant predictors of individual-level parameters in NARPD features included group membership, negative emotion (anxiety), constraint (nonaffective), communal positive emotion (affiliation), and agentic positive emotion (agency, incentive motivation) (all p≤0.05). Group membership (i.e., PPD status) was associated with higher NARPD levels. In terms of personality predictors, higher levels of negative emotion and agentic positive emotion were associated with higher NARPD levels, whereas higher levels of constraint and communal positive emotion were associated with lower NARPD levels. Of the level 2 predictors of elevation, negative emotion (anxiety), constraint, and agentic positive emotion were associated with the largest effect sizes. The variance component estimate for elevation (σ20) indicated that there remained significant variation in elevation that could be modeled beyond the selected predictors.

Slope is the critical growth parameter for the investigation of stability and change in NARPD features over time during undergraduate college because it directly indexes the rate and direction of individual change over time. As noted in the unconditional model results, the overall pattern for NARPD was a decreasing trend across the 4-year study period. In the level 2 prediction of slope for NARPD features, constraint and agentic positive emotion were significantly predictive of the rate of change in NARPD features (both p≤0.05; small effect of constraint and agentic positive emotion, but the latter showed a trend toward medium effect). The effects were such that higher baseline levels of constraint were predictive of less steep declines (or slight increases) in NARPD features over time, whereas higher levels of agentic positive emotion were predictive of greater rates of decline in NARPD features over time. The variance component estimates for rate of change (σ21) indicated additional significant variation in slope that could be modeled beyond the selected predictors.

Finally, in sensitivity analyses guided by the arithmetic and distributional properties of the dependent variable (the count of NARPD features), the unconditional and conditional models were refitted by replacing the existing outcome with its square root. This approach yielded a pattern of results completely consistent with those reported for the untransformed PD variables.

Discussion

For over 100 years, the assumption in psychiatry and clinical psychology was that PDs were relatively stable, enduring, pervasive, inflexible, and trait-like. Indeed, that characterization figured prominently in the

DSM-III and has remained even in the

DSM-5. However, with the advent of prospective longitudinal studies that addressed these theoretical assumptions in the

DSM, the ever-expanding body of literature has revealed that personality pathology is flexible, is malleable, and shows evidence of change over time. This pattern of evidence suggesting change was first observed in the LSPD (

35) and was confirmed by subsequent PD studies. Despite marked methodological differences in terms of measurement, sampling methodology, clinical status of participants, and other features, the overwhelming pattern observed for PDs across the other longitudinal studies of personality pathology is one of change, specifically declining pathology over time (

59–

62). Remarkably, all four of these longitudinal studies were carried out by psychopathologists with a focus on clinically significant personality pathology.

Regarding narcissistic psychopathology, only the current study (LSPD) and Cohen et al.’s Children in the Community Study (CIC) (

59) focus on narcissistic personality pathology found among individuals who were not preselected for some other disorder (which necessarily conditions results on the preselection factor in those other studies). Although the CIC did not use standardized clinical assessments for narcissistic pathology, it provided some evidence for declining levels over time of what the investigators termed pathological narcissistic traits (

63). The LSPD, therefore, is the only study that has examined the longitudinal course of clinically significant

DSM-defined NARPD features by using standard clinical assessments (i.e., IPDE), clinically experienced raters, a meaningful assessment schedule covering the first 4 years of college, and methodological safeguards to ensure the same participant was never evaluated more than once by any assessor. What, then, is the developmental course of clinically significant NARPD across the undergraduate college years? The course of NARPD over that time span is characterized by a great deal of heterogeneity in growth (

Figure 1) and by a general pattern of declining levels of NARPD. In short, similar to what we know about normal personality (

64,

65) and other PDs (

35,

41), NARPD is clearly not set like plaster (and certainly not engraved in granite, as some view the

DSM assumptions) during the first 4 years of college; moreover, it certainly does not increase for a majority of young people during that period. The data from the current study do not support, for this 4-year time frame and these participants, a pattern of increasing NARPD psychopathology.

The current study made use of the IGC methodology. The power of the growth curve approach has long been known to investigators leading longitudinal studies (

52,

54). The unconditional growth model for NARPD features provided compelling evidence of the declining pattern of NARPD features over time. A well-known and elegant aspect of the IGC methodology used in this study is that it allows researchers to tease apart the two major components of a growth curve, namely, overall elevation and slope (or rate of change). Therefore, this study was able to investigate between-participant difference variables that help to explain these two aspects of growth and development. The subsequent conditional (level 2) analyses that focused on personality dimensions known to be reflective of neurobehavioral personality systems, as theorized by Depue and Lenzenweger (

37–

40), provided insights into the personality factors related to the initial level of NARPD features as well as the rate of change for NARPD features. Given the finding of considerable change in NARPD over time, the findings of greatest substantive interest to this study were the roles played by constraint and agentic positive emotion. In short, higher baseline levels of constraint seemed to slow rates of change over the 4-year study period, whereas higher baseline levels of agentic positive emotion predicted faster rates of change (i.e., declines) in NARPD features. In the LSPD sample, NARPD features were highest, in general, at the beginning of the study period (the first year of college). It is entirely conceivable that many young adults arrive at college, fresh off the successes and triumphs of high school that helped them to gain admission, with something of an inflated or distorted sense of grandiosity (consciously aware of it or not) and that with time and experience, this narcissistic enhancement (even when pathological) may begin to abate. This developmental trend may be reflective of the important maturity principle so clearly articulated by Roberts and Mroczek (

65).

The results from this study cannot be juxtaposed with any other data in terms of clinically significant narcissistic pathology features assessed prospectively in a multiwave study across the first 4 years of college. The current results are highly consistent with those for narcissistic traits (informed by the

DSM system) from Cohen et al.’s CIC, as reported by Johnson et al. (

63) for a sample of young adults living in the community (note the considerable attrition in the CIC over time). Both the current results and those from the CIC provide evidence that pathological narcissism declines over time.

What implications do the current findings have for the so-called narcissism epidemic proposed by Twenge and colleagues (

22–

25)? The current findings highlight the need for a fine-grained, prospective longitudinal study of the same participants to illuminate patterns of change in NARPD. The comparison of trait levels among students who have been assessed in different cohorts offers some basis for discussion of potential change in a trait of interest over time, such as the discussion regarding the apparent increase in scores on normative trait narcissism measures across successive college cohorts. However, such comparisons are necessarily limited because they concern different people, in different samples, who are assessed at different time points (and different cohorts with associated secular trends).

Moreover, the current study revealed a finding of considerable methodological importance regarding the assessment of NARPD during the undergraduate college years: namely, the precise point at which one assesses college students for NARPD will matter. The LSPD data revealed that NARPD levels were highest in the early years of college and then trended downward over time, perhaps reflective of the effects of the well-known maturity principle, as noted above (

65). Evidence consistent with this principle comes from the LSPD from another analytic vantage point, namely, that a decrease in NARPD features over time is associated with decreasing levels of neuroticism and increasing levels of conscientiousness, occurring in parallel over time (

66). The results of this study demonstrate the clear fact that NARPD does not necessarily stand on its own as a singular construct. To the contrary, NARPD (and other PDs) is likely an emergent product of underlying personality systems (

37–

40); thus, any consideration of whether NARPD features are increasing or decreasing cannot be made without accounting for personality constructs. To this end, the current results, at minimum, point to the importance of nonaffective constraint and agentic positive emotion to the prediction of change in NARPD over the undergraduate college years. Results from an LSPD study by Dowgwillo et al. (

66) further underscore this point, in that as NARPD features decline, other personality systems show important changes as well. Thus, one cannot meaningfully discuss NARPD alone (whether increasing or decreasing over time) without reference to other personality systems.

Finally, the current findings are consistent with Wetzel et al.’s (

33) recent rigorous statistical analysis of NPI (measuring nonclinical or normal personality narcissism traits) scores over time in successive cohorts, suggesting a decline in NPI scores across the 1990s and into the 2010s. That said, the psychopathologist must bear in mind that Wetzel et al. focused on NPI scores, which, as noted above, are derived from a measure known to have numerous psychometric shortcomings and to not measure clinically significant narcissistic pathology. Rather, the NPI measures a construct that is wed closely to normative (nonpathological) trait narcissism (

6), and NPI items are infused with a good deal of normative self-esteem content (

13). Given that the current study used a unit of analysis that bears a far closer resemblance to pathological narcissism (i.e., NARPD, as defined by the psychiatric nomenclature and assessed with a field-standard interview administered by clinically sophisticated interviewers), the findings reported here have greater implications for a discussion of narcissistic pathology relevant to clinical science than for one involving normative trait narcissism. In short, the findings of the current study may have greater probative value for scientific discussions by psychopathologists and those with an interest in clinically significant narcissistic pathology rather than by normal personality psychologists or social psychologists. For example, psychopathologists and personality scientists with a clinical focus may find more substance to delve into than others in terms of the study’s clinically interesting questions. Such questions include, What accounts for the pathogenesis of NARPD (

67)? How is the disorder underpinned by neurobehavioral systems (

37–

40)? and How can NARPD go badly off the rails, so to speak, and veer into malignant narcissism (

17,

20,

68)?

One should bear in mind four caveats in understanding the IGC results for NARPD that were drawn from the LSPD database. First, the LSPD covered a 4-year period. Although 4 years is a developmentally meaningful time span, it is reasonable to suspect that PD development continues beyond a person’s early twenties. Clearly, the participants in this study should be followed across the life span, and that is the intention of the LSPD. The participants who were originally enrolled in the LSPD are now in their forties, and they are passing through one of the more complicated developmental periods in the life course. The plan is to reassess them several times during the latter decades of their lives. In doing so, growth functions for the participants will become greatly enriched, influenced not only by the passage of time and developmental hurdles but also by the inclusion of more observations that will allow for even more complex modeling of the various effects of interest.

Second, it should be noted that the indicators of the neurobehavioral systems studied are clearly fallible because they were drawn from psychometric assessment, and it is best to regard them as approximations of the underlying neurobehavioral systems hypothesized by Depue and Lenzenweger (

37–

40).

Third, it must be noted that this study has not exhausted the list of possible factors that could be included as between-participant variables for the level 2 model estimations. One could include other variables, such as contextual and experiential factors (e.g., parental rearing approaches, peer relations, social networks, rural vs. urban residence), as well as significant negative life events (e.g., trauma, neglect, maltreatment, unemployment, poverty, divorce, health declines, or death of a spouse, parent, or child), in the prediction of overall level of and rate of change in NARPD features over time. My laboratory is currently examining the potency of a measure of proximal process in the prediction of NARPD in this sample (

67). Proximal process represents a construct influenced in large part by the thinking of Vygotsky (

69) and proposes that healthy or positive development occurs when children are consistently presented with learning and complex experiential opportunities that are slightly above their current level of competence. Such a measure may help capture an early input into the development of NARPD and may be useful for the long-term prediction of overall level of and rate of change in NARPD.

Finally, because it was drawn from a university population, this study’s sample is more homogeneous in age, educational achievement, and social class than the U.S. population at large and consists only of young adults—features that may have differentially affected the study results. However, the current sample was ideally suited to address conjectures regarding NARPD during the undergraduate college years. As noted, adjustment to university life across the undergraduate college years (particularly the freshman-year transition) may have played a role in the changes I observed. In this context, however, it is essential to note that the IPDE assessments were based on an evaluation of functioning during the current year and during the past 5 years (i.e., a 5-year window) and were not merely reflective of current mental state or the most recent level of functioning. Also, LSPD participants were selected from a population (first-year university students) that might have been censored for some individuals most severely affected by PDs. However, 16% of the LSPD sample was diagnosed as having an axis II PD (full clinical thresholds) by the end of the study period, as assessed by using the highly conservative IPDE—a percentage that accords well with community studies (

70). Moreover, 45% (N=113) of the LSPD participants had received a lifetime (or current) axis I disorder diagnosis by the end of college. Kessler et al. (

71) found that 46.4% of the U.S. population received at least one axis I diagnosis in the original National Comorbidity Survey Replication. One must consider the consistency of the LSPD data with population-based epidemiologic data before ascribing undue levels of mental health pathology to the participants in this study merely on the basis of their university student status at initiation of the LSPD. Such a reminder would not come as a surprise to experienced clinicians who work in college mental health centers, where the nontrivial elevated prevalence of clinically significant psychopathology is unmistakable and represents a health care priority for many colleges and universities.