Psychotherapy pathways, or tracks, in psychiatry residency training supplement the standardized education in supportive, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral psychotherapies required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (

1). Pellegrino et al. (

2) previously described the formation and evolution of a tiered psychotherapy pathway within an academic psychiatry residency program. All residents interested in learning more about psychotherapy may participate in pathway meetings, and those with strong motivation may undertake intensive study to earn an area of distinction (AOD). The aims of pathway participation are to provide exposure to therapeutic modalities not taught within the core residency curriculum and to deepen knowledge of topics covered elsewhere in training.

Pathway meetings are held every other month during protected didactic time and feature volunteer speakers from both within and outside the institution. Topics vary from year to year and are selected on the basis of residents’ interest. Prior topics have included narrative therapy, technology in psychotherapy, trauma therapy in a correctional setting, psychodynamic perspectives on shame, and case discussions from different therapeutic approaches (e.g., psychoanalysis vs. dialectical behavior therapy). Supplementary evening presentations have included movie nights and career panels. Residents who wish to earn an AOD may do so by completing in-depth clinical study, scholarly writing, or curriculum development and teaching.

The pathway was originally formed in 2013, and all members were initially required to earn an AOD by intensively studying a specific therapeutic modality. In response to feedback, the pathway has since opened participation to all residents, regardless of their interest in earning an AOD. Pathway leaders have also broadened meeting topics and increased the flexibility of AOD requirements to serve residents who plan to practice across a variety of settings.

Although features of psychotherapy pathways have been described elsewhere (

3,

4), outcomes of participation have not been previously reported. This report assesses the effectiveness of the pathway described by Pellegrino et al. (

2) by surveying graduates who have earned an AOD. We sought to assess the pathway’s success in meeting its goals, examine the impact of participation on graduates’ career development, and collect feedback in order to enhance the pathway for future residents.

Methods

The University of Washington Institutional Review Board granted exemption for this study. Graduates who participated in the psychotherapy pathway and received an AOD between 2013 and 2020 (N=22), excluding the two graduates who are coauthors of this report (S.K.C., L.D.P.), received an e-mail invitation to participate in a voluntary, anonymous survey about their pathway experiences. The initial survey was sent in June 2021, with one follow-up reminder sent in July 2021. The survey was administered through the Research Electronic Data Capture tool (

5), a secure, web-based software platform designed for research studies.

In this cross-sectional survey, we assessed graduates’ current practice setting, amount of practice time (patient visits) devoted to 45- to 60-minute psychotherapy appointments, and graduation cohort (grouped by year). Two items regarding use of psychotherapy in current practice were included: “I am often able to incorporate psychotherapy techniques into my interactions with patients (regardless of appointment type or setting)” and “Using psychotherapy in my practice makes my work more meaningful.” Two additional items addressed the value of the pathway: “Participating in the psychotherapy pathway exposed me to many different psychotherapy modalities” and “Participating in the psychotherapy pathway facilitated a more in-depth understanding of one or more psychotherapy modalities of interest to me.” All four of these items were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale reflecting agreement with the statement (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree). The final three items were open-ended questions: “How did participation in the psychotherapy pathway influence your career development and/or current practice?” “What were the most satisfying parts of your psychotherapy pathway experience? What could have been improved?” and “Is there anything else you wish to add?”

Descriptive data for quantitative survey variables were computed by using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 27. We reviewed qualitative data from the last three questions and grouped comments into common themes. The themes created were then compared, and a final clustering of core themes was selected via consensus.

Results

Completed surveys were received from 13 of the 22 graduates (59%) invited to participate. Survey respondents were fairly evenly distributed across residency graduation cohorts: four respondents graduated between 2013 and 2015, four between 2016 and 2018, and five in 2019 or later.

Eight respondents (62%) reported practicing outpatient psychiatry, five (38%) reported practicing in private practice, three (23%) reported practicing in an outpatient academic setting, and two or fewer indicated that their practice settings included inpatient psychiatry, community psychiatry, collaborative care, colocated care, or emergency psychiatry. The practice setting categories were not mutually exclusive.

Four survey respondents (31%) indicated that they were not conducting any 45- to 60-minute psychotherapy appointments. Four respondents (31%) indicated that 25% or less of their patient visits included such appointments, and five respondents (38%) indicated that 76%–100% of their patient visits were devoted to such appointments.

Most respondents agreed that “participating in the psychotherapy pathway exposed [them] to many different psychotherapy modalities” (strongly agree or agree: N=12, 92%; neither agree nor disagree: N=1, 8%). Likewise, most respondents agreed that “participating in the psychotherapy pathway facilitated a more in-depth understanding of one or more psychotherapy modalities of interest to [them]” (strongly agree or agree: N=12, 92%; neither agree nor disagree: N=1, 8%). All respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “I am often able to incorporate psychotherapy techniques into my interactions with patients (regardless of appointment type or setting),” and with the statement, “Using psychotherapy in my practice makes my work more meaningful.”

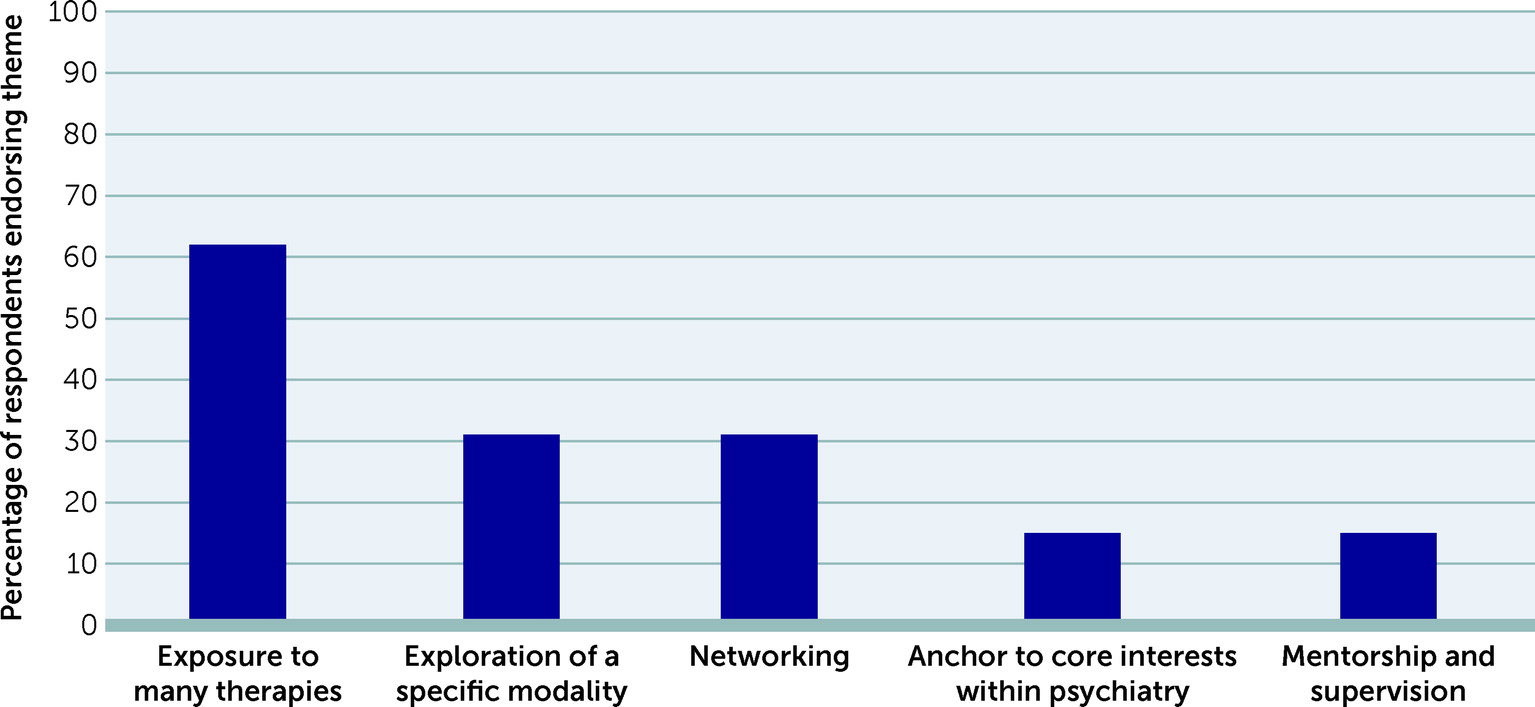

Several common themes emerged from open-ended responses regarding the most satisfying elements of pathway participation (

Figure 1). Eight respondents (62%) named exposure to a broad array of therapeutic modalities as most valuable. Four respondents (31%) noted that their participation facilitated concentrated exploration of a specific therapeutic modality, and two respondents (15%) shared that the pathway helped anchor them to their core interests within psychiatry. Furthermore, four respondents (31%) shared that they valued meeting clinicians who work in different settings and learning about the varying ways therapists practice, and two respondents (15%) expressed appreciation for access to mentorship and supervision opportunities.

In addition, respondents commented on the ways pathway engagement influenced their career development. Among those devoting more than 75% of their patient visits to psychotherapy, four respondents (80%) shared that their participation shaped their professional interests. For example, one respondent noted, “My work with [a faculty pathway leader] . . . was a major contributor to my desire to work with patients exclusively in a psychotherapeutic context.” Among those devoting no more than one-quarter of their patient visits to psychotherapy, five respondents (63%) shared that the pathway taught them skills that they utilize across a range of encounters. One such respondent wrote, “This pathway by far was one of the most educational experiences in my residency training and I utilize [what I learned] in most, if not all, of my assessments and interactions with patients. [What I learned] increases [the] effectiveness of interventions, including medication management . . . and improves rapport.”

Discussion

The study results indicate that our pathway is meeting its intended objectives: to expose residents to a variety of psychotherapeutic modalities and to facilitate targeted exploration of specific modalities of interest. Free-text responses included multiple favorable comments on the breadth and depth of education received through the pathway. Moreover, several respondents remarked on the value of meeting practicing therapists from diverse backgrounds who utilize different frameworks. Limitations of having academic faculty teach psychotherapy exist, because this arrangement presents only one perspective among many on how therapy may be practiced. As such, our pathway provides important opportunities for residents to meet role models who have built productive careers in psychotherapy across different settings (

6).

From an early point in its evolution, our pathway has catered to all residents with an interest in psychotherapy, regardless of their career plans. A majority of AOD graduates to date have chosen career paths other than a psychotherapy-based practice (

2), and a majority of survey respondents (N=8 of 13) indicated that they devoted 25% or less of their patient visits to psychotherapy. Importantly, respondents who specialize in psychotherapy and those who do not both reported that their pathway experiences were helpful to their career development. Specifically, the latter group described gaining knowledge and skills that they utilize across diverse settings to build rapport and increase the effectiveness of their practices. Psychotherapy is recognized as a fundamental element of a psychiatrist’s identity and as essential to effective work with patients (

6–

8), even though it represents a declining portion of outpatient psychiatric visits in the United States (

9). Educators thus have a responsibility to provide psychotherapy training that will be useful for psychiatric residents, regardless of where those residents choose to practice (

10). Our pathway may offer one means of providing such teaching, in concert with a residency’s core psychotherapy curriculum.

Limitations of this study included its sample size, which was small and drew from one institution, such that the findings are not generalizable to psychiatrists who have participated in psychotherapy tracks of other residency programs. The survey also had a response rate of 59%, and individuals who responded may have held stronger views about their pathway experiences than those who did not respond. Moreover, when considering the impact of pathway participation on current practice, respondents at times may have conflated their pathway participation with the psychotherapy training that they received through rotations, although most respondents also named specific pathway experiences that had been meaningful to their professional growth.

Future directions include implementing ideas from respondents for adapting the pathway to serve residents with varying levels of interest in practicing psychotherapy. For residents intending to build dedicated psychotherapy practices, we may explore mechanisms for targeted matching of residents with mentors, including individuals outside our local community. For residents intending to work in other settings, we will consider developing event series to teach psychotherapeutic skills that may be readily incorporated into brief medication management visits (e.g., Shaligram et al. [

11]).

Conclusions

This report describes the design of and results from the first survey of graduates from a psychotherapy pathway within a psychiatric residency program. Our results highlight the educational and professional benefits of developing such a pathway for residents with varying career plans. These findings may be of interest to other psychiatry residency programs seeking options to augment their psychotherapy training or to modify existing psychotherapy pathways.