Lesbian, gay, bisexual (

1–

3), and transgender (

4–

6) individuals report higher rates of exposure to physical and sexual abuse as children and to physical and sexual assault as adults relative to heterosexual and cisgender individuals. Perhaps consequently, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) disproportionately affects people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ). In the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, participants identifying as gay or bisexual exhibited a PTSD prevalence twice that of heterosexual participants (

7). No comparable epidemiological data have been published on PTSD rates among transgender individuals; however, the rate of PTSD diagnosis in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, as recorded in electronic medical records, is approximately 50% higher among transgender than among cisgender veterans (

8).

Some LGBTQ patients with PTSD report impactful experiences of minority stress (

9), such as discrimination or stigmatization, or identify

DSM-5 PTSD criterion A traumas involving LGBTQ identity (e.g., gay bashing), which may influence how PTSD symptoms manifest or may trigger episodes (

10–

15). Minority stress may also aggravate other risk factors for developing PTSD, such as a less secure attachment style (

11,

16–

18). LGBTQ individuals are also relatively more likely than heterosexual or cisgender individuals to experience material stressors and interpersonal losses, such as losing housing or experiencing parental or community rejection, which can hinder adaptation to traumatic events (

1,

19).

Despite high rates of trauma exposure and PTSD diagnosis, the efficacy of therapies specifically for PTSD has not been examined for the LGBTQ population (

20). Research on the effects and tolerability of PTSD therapies among LGBTQ patients is critical given the outsized impact of PTSD and the need for PTSD treatment in this population. For example, at a free LGBTQ-oriented mental health clinic at a teaching hospital in New York City, 65% of patients seeking treatment over a 2-year period reported having a potential PTSD diagnosis, in accordance with a recommended cutoff score on the PTSD Symptom Checklist for DSM-IV (

21). Some LGBTQ patients with PTSD may benefit from therapists who explicitly consider the role of identity factors or other potentially important and preoccupying developmental (e.g., family rejection, alienation) or contemporary experiences (e.g., internalized stigma) beyond the index trauma (

22). Application of trauma-focused therapy techniques may also require additional sensitivity toward the contexts and realities of different LGBTQ patients. For example, in vivo exposure exercises in prolonged exposure (PE) therapy may need to be adapted to the needs of some individuals in order to realistically titrate exposure to environments and situations in which they are at genuine heightened risk for anti-LGBTQ discrimination or violence (

12).

Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs) such as PE therapy and cognitive processing therapy, often considered mainstay evidence-based treatments for PTSD, can be effective (

23) but are often associated with high dropout rates (30%–50%) and incomplete clinical response (approximately 50% among those who complete treatment) (

24,

25). In clinical trials, exposure-focused treatments have been shown to have higher dropout rates among African Americans (

26,

27) and individuals with extensive experiences of childhood abuse (

26,

28) relative to their peers, which may limit the reach of these therapies among polytraumatized LGBTQ patients with intersectional minority identities. Establishing the efficacy of alternative therapeutic modalities for PTSD will likely be critical to lessening the outsized burden of PTSD in the LGBTQ population because no single therapy or primary therapeutic focus (e.g., structured, repeated exposure to trauma memories) will be effective or tolerable for all patients.

To address these specific treatment needs, we conducted an open trial of trauma-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy (TFPP), an affect- and attachment-focused psychotherapy (

29), to treat PTSD among LGBTQ patients. TFPP was adapted from panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy (

30), the only empirically supported, efficacious non–exposure-focused psychodynamic therapy for panic disorder and other anxiety disorders (

31–

33). One aim of TFPP is to improve patients’ ability to tolerate, understand, and manage intense emotions that suddenly and unpredictably appear, a phenomenon related to patients’ tendency to reexperience traumatic events in the here and now, unexpectedly and when danger is not present. TFPP engages the psychological meanings of symptoms and their relationship to traumatic events to help patients better understand the emotional underpinnings of symptom triggers and to untangle ways in which emotional meanings of trauma affect current experiences. TFPP is used to help patients elucidate, tolerate, and work through intrapsychic conflicts potentially contributing to PTSD symptoms, such as the difficulty patients often have in experiencing or expressing anger, which may be linked in an individual’s mind to traumatic experiences (e.g., as an identification with one’s abuser). TFPP was developed with patients with complex PTSD in mind; these individuals often have multiple prior traumas with no clear index trauma (

34). TFPP incorporates opportunities for patients to explore, within a psychodynamic developmental framework, the broader context of their symptoms and difficulties in their lives, including but not limited to LGBTQ identity and minority stress (

29). In this study, TFPP was delivered by teletherapy to 14 LGBTQ patients with PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Patients

No deviations from the registered trial protocol were made. All screening, assessment, and psychotherapy for the study took place over a secure teletherapy platform. Patients provided informed written consent for participation, and the protocol was approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of PTSD in accordance with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) (

35), identifying as LGBTQ (i.e., as a sexual or gender minority individual), having stable psychiatric medications for the past 2 months and agreeing to remain on a stable dose or combination during the study treatment, and being ages 18–65. Exclusion criteria were psychosis; bipolar I disorder; severe suicidality (e.g., patients demonstrating suicidal intent or plan); primary substance use disorder; severe major depressive disorder, defined as a score ≥24 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (

36); and neurocognitive or developmental disorders likely to interfere substantially with participating in study procedures and psychotherapy.

Patients were seeking treatment and were referred to the study via Weill Cornell Medical College, advertisements on Facebook and Instagram, self-referral, or community referral. Patients were administered a telephone screening for presence of PTSD and absence of major exclusion criteria before being invited to complete a more thorough assessment. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (

37) was administered to thoroughly determine the presence of symptoms related to comorbid conditions and exclusion criteria.

Twenty-seven patients were screened, 21 were offered an intake assessment interview, and 14 completed the assessment and were invited to begin treatment. (A CONSORT diagram and additional details on the study’s design and methods [e.g., therapist training, adherence] are available in the online supplement to this article.)

Trauma-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

TFPP is a manualized, brief, 24-session, twice-weekly psychodynamic therapy developed specifically for the treatment of PTSD (

29). TFPP focuses on how trauma disrupts attachment (

17,

38) and the capacity for mentalization and symbolization (

39) and on intrapsychic, trauma-related conflicts, all of which can lead to unsuccessful attempts to avoid engaging with the psychological meanings or the impact of traumatic experiences that lead to symptoms. Psychodynamic interventions such as clarification, confrontation, and interpretation help patients improve reflective functioning regarding the psychological meanings and contexts of symptoms, reduce dissociation and affective numbing (

40), identify and work through traumatic repetitions and intrapsychic conflicts, and develop better narrative coherence regarding their trauma and life history. The therapist attends to and addresses transference as an important arena for exploring trauma-related dynamics, which commonly include conflicts related to trust, fear of dependency, and expression of anger. Importantly, PTSD symptoms are used as a lens through which to understand underlying meanings and dynamics. The therapist may tactfully and carefully solicit details about emotionally relevant aspects of the traumatic event or may focus on elements of the event that evoke high degrees of conflict (e.g., gaps in memory, confusions) in the service of not modeling avoidance of trauma-related memories or their meanings (

41). However, no structured exposure exercises or in-session discussions about the details of a patient’s trauma are required, and no homework is assigned.

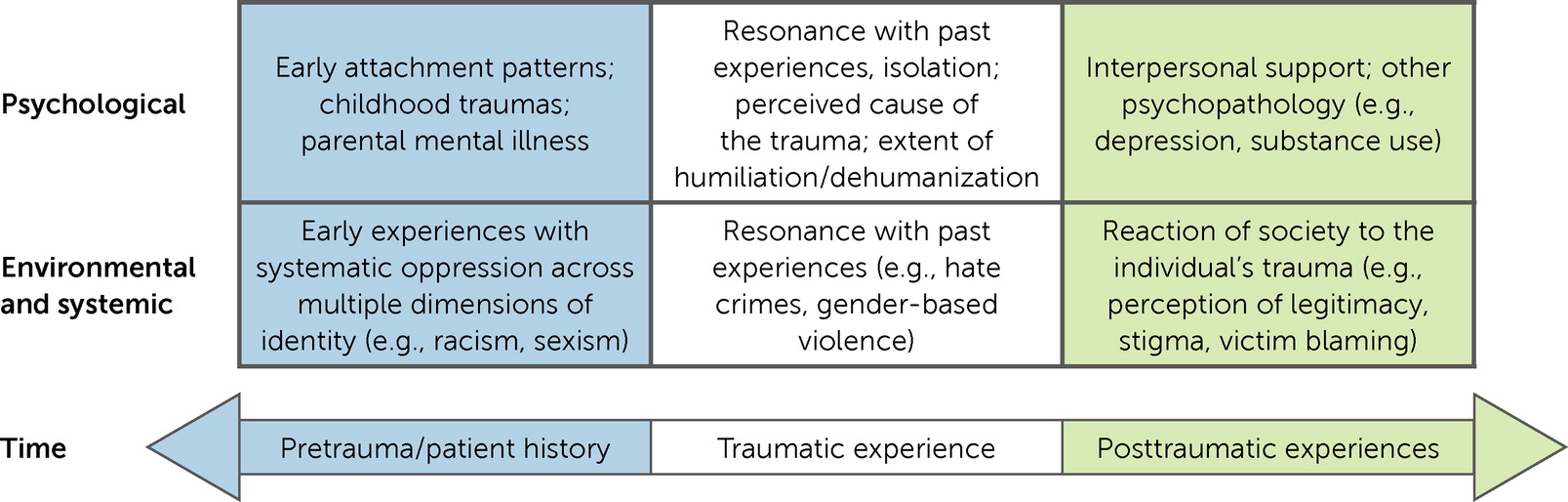

Factors related to LGBTQ identity and minority stress were conceptualized within TFPP’s framework to incorporate systemic and cultural influences on patients’ experiences and patients’ adaptation to traumatic events into the treatment approach. For example, this model considers how the impact of traumas experienced as an adult may be amplified and overlaid by past experiences of oppression or discrimination (

Figure 1). Although therapists followed the American Psychological Association’s recommendations for LGBTQ-affirmative psychotherapy (

42), per TFPP’s nondirective psychodynamic model, therapists did not set an a priori agenda to discuss LGBTQ-related topics. Rather, therapists were guided to be attentive to potential avoidance of and conflicts related to discussing LGBTQ identity and to actively address these issues. Therapists were encouraged to explore connections between PTSD symptoms and both identity-related information and the therapeutic process (e.g., anxiously experiencing the therapist as a potential oppressor, experiencing PTSD intrusions during sex) as they emerged during sessions. All treatments were delivered over a secure teletherapy platform (video and audio) because the study occurred during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States (September 2020–June 2021).

Therapists

Seven psychotherapists delivered TFPP: one Ph.D clinical psychology intern, one M.D. psychiatry resident, three Ph.D. psychology postdoctoral fellows, one M.D. psychiatry psychotherapy fellow, and one early-career M.D. psychiatrist. All but one therapist was new to delivery of TFPP, only two therapists had ever delivered a manualized psychodynamic therapy, and two therapists had never delivered a psychodynamic therapy. Therapists had an average of 1 year of postdoctoral experience. Six therapists were cisgender women, and one was a cisgender man. All therapists participated in a 1.5-day training program and attended weekly group supervision.

Therapists were supervised weekly for 1 hour in groups of three to four. Supervision was led by the TFPP developer (B.L.M.), and therapists were cosupervised by the primary study author (J.R.K.). Therapists presented case material, including videotaped sessions, to the supervision group. TFPP adherence ratings were made for 15 randomly selected taped sessions, and raters (B.L.M., J.R.K.) used the standardized TFPP adherence measure (available on request; see online supplement). In this study, 93% (N=14 of 15) of rated sessions met adherence standards (score ≥4 on at least five of seven items; score range 0–6, with higher scores indicating greater adherence).

Measures

All observer-reported measures were delivered by two independent clinical assessors (C.L., A.M.), medical students volunteering at the Weill Cornell LGBTQ Wellness Qlinic, who were uninformed about specific study hypotheses. Assessors were trained and supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist (J.R.K.). Patients were compensated only for participating in study assessments ($50 for baseline assessment, $30 for each subsequent assessment), not for attending therapy sessions. Psychotherapy was provided gratis.

Primary Outcome

The CAPS-5 is the best-established observer-based interview measure for diagnosis and assessment of PTSD on the basis of

DSM-5 criteria (

35). Individual items reflecting

DSM-5 criteria are scored from 0 to 4 by using a structured guide, where higher scores reflect more severe symptoms and scores ≥2 reflect a clinically significant symptom that contributes to making a PTSD diagnosis. The CAPS-5 total score was our primary study outcome. Patients were assessed at baseline, week 5, termination (week 12), and 3 months posttreatment. Clinical response on the CAPS-5 was defined a priori as a 30% reduction from baseline CAPS-5 total score (

43). The “last observation carried forward” strategy was applied to patients who did not complete the trial, exclusively for the metric of clinical response. We also analyzed change in symptoms of dissociation (measured by two items) among individuals reporting dissociation at baseline. Ten videorecorded assessment tapes were double-rated and analyzed for interrater reliability (total CAPS-5 score: intraclass correlation coefficient [model 2,1]=0.91; presence of CAPS-5 PTSD diagnosis: κ=1.00).

Secondary Outcomes

Complex PTSD symptoms.

The International Trauma Interview (ITI) developed by the

ICD-11 complex PTSD working group was used to assess complex PTSD symptoms (

44). Meeting at least one criterion each (score ≥2) from the affective dysregulation, identity, and interpersonal domains of the measure indicated a diagnosis of complex PTSD per

ICD-11 criteria. The ITI was collected at all time points.

Depression and anxiety.

The HRSD (

36) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) (

45), well-established semistructured interviews to assess general mood and anxiety symptoms, were collected pre- and posttreatment (termination). We used the reconstructed versions to more specifically differentiate general anxiety from depression symptoms (

46).

Psychosocial impairment.

The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) is a self-report measure that assesses the degree to which psychiatric symptoms interfere with the ability to function in work, social, and family roles (

47). The SDS was administered at baseline, week 5, and treatment termination.

Statistical Analysis

All available data for patients were analyzed by using an intention-to-treat method. Change in clinical measures during the study was analyzed in a linear mixed model by using the R packages lme4 (

48) and lmerTest (

49). An a priori power analysis was calculated for a mixed-model analysis of CAPS-5 score change, aiming to detect a large effect size (α=0.05, 99% power, three measurements, repeated-measures r=0.50, Cohen’s d=1.00) commensurate with within-groups CAPS-5 effects for efficacious PTSD psychotherapies (

43,

50) for a target sample of N=15.

For the primary outcome (CAPS-5) and all outcomes collected at three time points, a two-level mixed-model structure was set, with a random effect of slope (level 2) nested in a random person-level intercept (level 1). Time was modeled as a linear effect of assessment (0, 1, 2), and a significant fixed effect of time reflected reliable change in that measure during treatment. For outcomes assessed at only two time points (reconstructed HRSD and HARS), no random slope was specified because models could not converge in this small sample. Beta weights for reported tests reflect estimates of slopes of change, and Cohen’s d was also provided to describe the magnitude of average within-person change on a given outcome measure.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Patients’ baseline characteristics (N=14) are reported in

Table 1. A majority of patients (N=11, 79%) identified a sexual assault as an adult or sexual abuse as a child or adolescent as their criterion A trauma to anchor the CAPS-5 interview. Of note, the sample was not treatment-naïve; patients reported an average of 1.6 prior psychotherapies focused on treating their PTSD, and, on entering the trial, most patients (N=11, 79%) were actively taking psychiatric medications, which were held constant throughout the trial.

Treatment Retention and Adverse Events

Two patients (14%) dropped out of treatment, both during week 5: one patient dropped out after completing their midpoint assessment at session 10 because they did not find the therapy to be helpful, and one patient dropped out after session 9 because of significant difficulties meeting study demands (e.g., attending therapy sessions). All other patients completed all 24 sessions of TFPP.

No study-related adverse events were documented. One patient had a medical event (myocardial infarction) requiring hospitalization and paused study-related treatment for 2 weeks; this patient completed therapy.

Primary Outcome

Termination.

Of 14 patients included in statistical analyses, 10 (71%) met criteria for clinical response (improvement of ≥30% in CAPS-5 total score from baseline to termination). CAPS-5 PTSD symptoms significantly improved during treatment (mean decrease=−21.8, d=−1.98). Seven (50%) patients also no longer met

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD. On average, patients exhibited a significant improvement in CAPS-5 scores across the three assessments (β=−10.8, 95% CI=−16.3 to −6.0, t=−4.42, df=5.7, p=0.005, d=−1.98). The breakdown of clinical outcomes by PTSD symptom cluster is presented in

Table 2. Among patients who reported symptoms of dissociation on the CAPS-5 at baseline (N=6, 43%), improvement in dissociation occurred (β=−1.5, 95% CI=−2.6 to −0.6, t=−3.20, df=3.2, p=0.030).

Follow-up.

Eleven patients were assessed at the 3-month posttreatment follow-up. The two patients who dropped out of the study and one patient who completed treatment were not reachable at follow-up. One patient who did not show clinical response at study termination attained response by the 3-month follow-up. Ninety-one percent (N=10 of 11) of patients assessed at follow-up, or 71% (N=10 of 14) of the total sample, met criteria for clinical response, counting patients not assessed at follow-up as nonresponders. We found no evidence of symptom recurrence between termination and the 3-month follow-up, and patients generally experienced a small improvement in symptoms between these time points (β=−3.6, 95% CI=−6.5 to −0.8, t=−2.64, df=7.0, p=0.034). No patients reported seeing a therapist outside the study or a change in psychiatric medication during the 3 months following termination, and only two patients who completed therapy attended an available booster session during the follow-up interval.

Secondary Outcomes

ICD-11–defined symptoms of complex PTSD, as measured by the ITI, significantly improved during treatment (β=−3.3, 95% CI=−5.8 to −0.8, t=−2.7, df=8.5, p=0.024, d=−0.63), with the bulk of improvement occurring in the second half of treatment (

Table 2). Both anxiety (β=−6.1, 95% CI=−9.7 to −2.8, t=−3.7, df=7.4, p=0.007, d=−0.89) and depression (β=−8.6, 95% CI=−13.4 to −3.5, t=−3.6, df=7.8, p=0.008, d=−0.88) improved significantly over the course of treatment, as measured by the reconstructed HARS and HRSD, respectively. Psychosocial impairment on the SDS also improved significantly (β=−3.9, 95% CI=−6.7 to −1.1, t=−2.76, df=16.0, p=0.014, d=−1.02).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that LGBTQ patients with a primary diagnosis of PTSD who received 24 sessions of TFPP experienced significant improvement in PTSD symptoms during treatment, with a high rate of clinical response (71%) that was maintained at the 3-month follow-up. The cohort of LGBTQ patients in this study had typically experienced sexual assault; reported severe, chronic (mean duration=59.4 months) PTSD symptoms on the CAPS-5; and had a high rate of complex PTSD (43%) as defined by the

ICD-11. TFPP was well tolerated, with 12 (86%) patients completing all therapy sessions. These high rates of treatment completion and clinical response are promising; nearly all patients had attempted at least one PTSD-focused therapy that was not effective in achieving PTSD remission before entering the study, and dropout rates in trauma-focused PTSD therapies can be high, estimated at 42% in a recent meta-analysis (

51). Patients experienced improvements in symptoms of complex PTSD (e.g., affective numbing), depression, general anxiety, and psychosocial functioning. These findings provide further evidence that therapies that do not focus on therapist-guided exposure to trauma memories (e.g., interpersonal psychotherapy [IPT]) may be effective in treating PTSD (

43,

50).

In this trial, therapists used an LGBTQ-affirming approach to treatment (

42) and aimed to flexibly integrate LGBTQ identity and minority stress into TFPP case conceptualization and the therapeutic process. This approach may partially account for TFPP’s achievement of high rates of clinical response and treatment completion; psychotherapies that are culturally adapted to specific groups tend to demonstrate advantages of small to medium effect sizes compared with unmodified treatments (

52). In further qualitative research with data from interviews at study termination, we will assess the impact of both general and LGBTQ-specific therapy process factors identified by patients. On the basis of the supervisory principles and qualitative findings from this trial, we are preparing additional research studies concerning treatment of identity-related trauma within a TFPP or psychodynamic framework (e.g., attending to transference informed by identity-based discrimination or oppression).

Some patients may have responded preferentially to the specific therapeutic frame, focus, and interventions of TFPP. In contrast to trauma-focused CBTs, TFPP is intended to address how PTSD can disrupt the capacity to reflect on and make sense of both internal experiences and the minds of others (i.e., mentalization) (

39,

53), particularly in regard to trauma-related conflicts, and to address the often profound disturbances in attachment and interpersonal relatedness that can be sequelae of trauma (

17,

38,

54). TFPP’s exploratory, interpretive interventions are used to help patients engage their capacity to reflect on and integrate dissociated affects and psychological meanings and to address unconscious conflicts, fantasies, and repetitions contributing to PTSD symptoms. Each family of PTSD therapies may be more helpful, on average, for specific types of patients than for others, and randomized comparisons with other treatment interventions can help reveal which patients may particularly benefit from TFPP relative to other efficacious therapies (

26). For example, in a separate clinical trial for PTSD, patients identifying sexual trauma as their criterion A PTSD anchor were found to have superior PTSD outcomes with IPT, another attachment- and affect-focused psychotherapy, compared with PE therapy (

55).

Finally, early-career therapists who delivered TFPP generally achieved high treatment adherence. This is noteworthy because most study therapists had not previously delivered TFPP, and two were entirely new to delivering psychodynamic therapies.

This study had several limitations. Although the observed treatment retention and clinical response rates are encouraging, this study was a small (N=14) open trial, which can have a bias toward positive results (

56). To test the efficacy of TFPP, further study is required among LGBTQ individuals in a randomized comparison against another intervention for PTSD, likely PE therapy. We are also testing TFPP compared with treatment as usual in an ongoing randomized controlled trial among veterans with PTSD who did not respond to or dropped out of PE therapy or cognitive processing therapy at three VA hospitals in New York City (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03755401).

The therapeutic processes most associated with therapeutic change in TFPP are unknown. In panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy, the treatment from which TFPP was adapted, a greater focus both on the therapist’s interpretation of dynamics surrounding symptoms (

57) and on in-session patient emotional expression (

58) predicted greater subsequent improvements in panic symptoms and development of symptom-specific reflective functioning, which mediate symptom relief (

59). We also did not assess LGBTQ-related minority stress and its impacts over the course of therapy, which may have helped to elucidate the extent to which TFPP successfully addressed these factors and whether better adaptation to minority stress also helped relieve PTSD symptoms (

60).

Although our cohort was socioeconomically diverse (64% [N=9] were low-income patients on Medicaid), diversity was not reflected in the racial-ethnic composition of our sample, with only four patients identifying as persons of color. Furthermore, only one patient identifying as male participated in the therapy. Gathering more data on the utility of TFPP for gender minority (e.g., transgender) patients will be essential (

15).

Conclusions

TFPP is an affect- and attachment-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy that can potentially address aspects of PTSD that differ from those addressed by trauma-focused CBTs and shows promise as an effective treatment among LGBTQ patients with PTSD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the therapists involved in the study for volunteering their time and effort to treat participating patients: Robin Brody, Psy.D., Alyson Gorun, M.D., Rebecca Klein, M.D., Jessica Kovler, Ph.D., and Kibby McMahon, Ph.D. The authors also thank the patients in this study for their time and effort participating in research assessments and the study intervention and Marylene Cloitre, Ph.D., and Neil Roberts, Ph.D., for sharing the International Trauma Interview for complex posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms before its general dissemination. Finally, the authors thank Chloe Roske, B.A., for her support in preparing revisions of the manuscript.