Specimens

Urine is used most often to test for drugs because it is obtained easily and concentrations of drugs in urine are relatively high (K Wolff et al, Addiction 1999; 94:1279). Ingesting large quantities of liquids, taking diuretics or adding water or household bleach to a urine specimen can mask illicit drug use. Blood is useful for quantitative determinations, but many abused substances leave the blood relatively quickly. Where there is a well-accepted relationship between blood concentrations and pharmacological effect, as with ethanol, blood testing can be helpful. Saliva may be particularly useful for assessing drugs taken too recently to be detectable in urine. Testing procedures may affect saliva concentrations; saliva is usually slightly more acidic than plasma, but when stimulated to collect sufficient volume for a sample, it may become more basic, which can alter the saliva-to-plasma (S/P) ratio. Smoking or eating can contaminate a saliva sample. Breath testing is useful for volatile substances, especially alcohol, because urine alcohol levels do not correlate well with blood alcohol levels, while breath alcohol does. Sweat patches worn for 7 days have been used to monitor patients in the criminal justice system or in drug treatment facilities. Environmental contamination can lead to false-positive results (DA Kidwell and FP Smith, Forensic Sci Int 2001; 116:89). Hair gives a better long-term measure (1–6 months) of substance abuse than urine because drugs stored in hair remain there as the hair grows out. The concentration of drugs in hair varies with hair color, hair structure and growth rates. Shampoos, bleaches or dyes can alter drug concentrations in hair. Volatile drugs like marijuana may adhere to hair and give false-positive results (R Wennig, Forensic Sci Int 2000; 107:5).

Drugs

Blood and breath concentrations of alcohol correlate more closely than urine concentrations with central-nervous-system impairment.

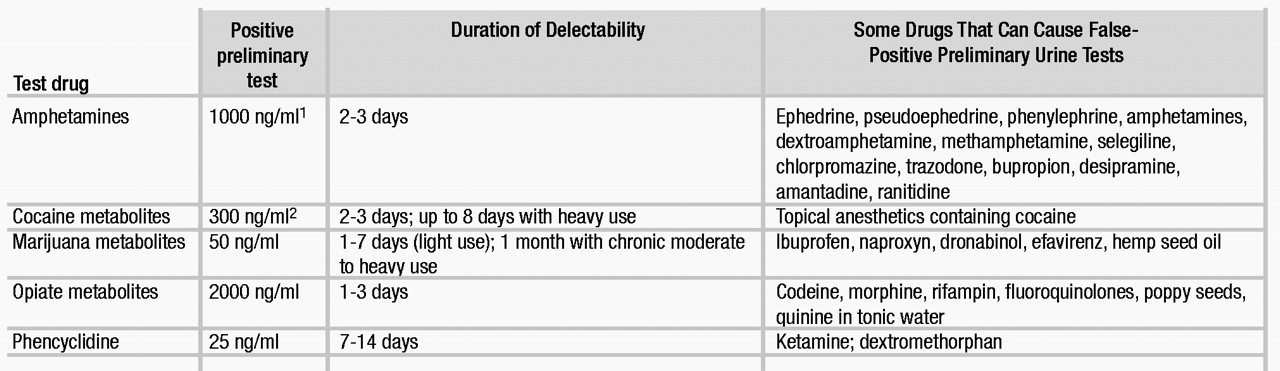

False-positive determinations are especially common with amphetamines. Using a second immunoassay to double-check positive results can reduce the number of false positives. The exact substance present can be determined by confirmation testing.

Marijuana is converted into several metabolites; among these, δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid can be found in urine in high concentrations for the longest duration of time. Positive tests from passive inhalation of marijuana smoke or from consumption of hemp-containing foods found in health-food stores (such as nut butters or cold-pressed cooking oil) are unlikely (G Leson et al, J Anal Toxicol 2001; 25:691).

Cocaine has a short half-life (about 1 hour); it is largely metabolized to benzoylecgonine, which has an elimination half-life of about 71/2 hours and is excreted in urine (RT Jones, NIDA Res Monogr 1997; 175:221).

Benzodiazepine immunoassays are standardized to a single benzodiazepine, such as nordiazepam (a diazepam metabolite), and cross-reactivity to other benzodiazepines is variable. If cross-reactivity to a benzodiazepine with a relatively short half-life, such as lorazepam (Ativan, and others), is low, and only a small dose of drug was taken, then the duration of a positive urine finding will be short compared to a longer half-life benzodiazepine with higher cross-reactivity, such as diazepam (Valium, and others).

Opiate immunoassays are highly sensitive for compounds showing structural similarity to morphine, such as codeine, 6-acetylmorphine, and dihydrocodeine, but less sensitive to more structurally dissimilar opioids such as oxycodone (Oxycontin, and others) or meperidine (Demerol, and others).