Over the past century and a half, posttraumatic syndromes have been reported in the medical literature under a variety of names, including railway spine, war neurosis, shell shock, soldier’s heart, combat fatigue, and rape-trauma syndrome. It was not until 1980, however, with the third edition of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (

1), that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) first appeared among the anxiety disorders in the DSM classification. Today we recognize that PTSD is a common disorder, ranking as the second most prevalent anxiety condition in the United States, after social anxiety disorder (

2). PTSD tends to be a chronic, disabling disorder and is associated with high rates of comorbidity, social and occupational impairment, and health care costs, comparable to those of other severe mental illnesses. Estimates suggest that with the increasing rates of trauma worldwide, PTSD is on track to become a major global public health problem.

In this article, we review the current knowledge about PTSD, beginning with a definition and discussion of the epidemiology and illness course. An examination of the neurobiological, psychological, and social factors that affect the development of PTSD follows. We then discuss the assessment of trauma and PTSD and review treatment outcome data, focusing on developments reported in the past 5 years. We conclude with a brief discussion of the limitations of our current understanding of PTSD and possible directions for future research.

Definition

PTSD is distinct from other psychiatric disorders in its requirement for exposure to an external, traumatic stressor. As defined in DSM-IV, this is an event that involves life endangerment, death, or serious injury or threat and is accompanied by feelings of intense fear, horror, or helplessness. Individuals who experience a trauma of this nature may develop symptoms that fall into three distinct clusters: reexperiencing phenomenon; avoidance and numbing; and autonomic hyperarousal. The DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Table 1) require that a minimum number of symptoms from each cluster be present (one or more reexperiencing symptoms; three or more avoidance/numbing symptoms; two or more hyperarousal symptoms) and that they coexist for at least 1 month after the trauma and are associated with significant distress or functional impairment (

3). Symptoms that have been present for 1 to 3 months are termed

acute, whereas those that persist beyond 3 months are considered

chronic. The development of symptoms 6 months or more after the trauma is termed

delayed onset. Similar criteria have been set forth by the World Health Organization (

4), although the WHO criteria place less emphasis on emotional numbing and require evidence that symptoms arose within 6 months of the trauma.

Assessment

Despite its high prevalence, PTSD remains an underrecognized disorder. Proper identification of those at risk is complicated by a number of factors. Individuals may be reluctant to seek treatment because of the stigma associated with trauma and mental illness, feelings of guilt and discomfort, or fear of reprisal to self or loved ones, particularly if the trauma is recent or ongoing. Health care providers often fail to inquire about trauma, largely owing to time constraints or personal discomfort with the topic or because they do not know how to inquire about trauma. Other complicating factors include the high diagnostic threshold for the disorder and high rates of comorbidity and symptom overlap with other mental illnesses.

Screening for trauma exposure is the first step in PTSD assessment. It is important to obtain a longitudinal history, including evaluation of traumatic experiences throughout the person’s life and for each event assessing the following: age at the time of trauma; duration of trauma (single, recurrent, or ongoing); type of trauma; if interpersonal, relationship to the perpetrator; and response and perceived impact of the event. This information should be elicited at the initial evaluation and updated at periodic intervals during the course of treatment. Several brief scales have been developed to collect history related to general trauma exposure (

122,

123) as well as to specific traumatic experiences, such as sexual abuse (

124). A more extensive trauma history can be obtained at follow-up, ideally in a quiet, private setting where the clinician can support the patient in discussing these distressing experiences.

Evaluation for PTSD includes assessment of each symptom cluster—reexperiencing, avoidance and numbing, and hyperarousal. Several psychometrically validated scales have been developed to facilitate this process. Although not a substitute for a clinical interview, rating scales can enhance clinical practice in several ways. They can identify patients at high risk of PTSD, they can be used to confirm the diagnosis, assess illness severity, identify target symptoms, monitor treatment outcome, and provide patient education, and they can serve as a source of documentation.

A variety of self-rated and observer-based scales are used in evaluating PTSD symptoms. Several brief screening instruments have been developed and validated (

125–

127) to facilitate PTSD recognition. These instruments are particularly useful in primary care and mass trauma situations, where they help identify those who need a focused clinical evaluation. More detailed symptom screening instruments that assess the full range of PTSD symptoms, including symptom frequency, severity, and related distress and impairment, may be helpful in psychiatric practice. Several validated, self-rated measures include the PTSD Checklist (

128,

129), Impact of Event Scale–Revised (

130), and the Davidson Trauma Scale (

131). Structured diagnostic interviews are used in clinical research, where they are considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of PTSD. Two of the most widely used scales in this category are the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (

132) and the Structured Interview for PTSD (

133). A useful tool for interval symptom assessment during treatment is the Short PTSD Rating Interview (

134), which also assesses somatic malaise, work and social functioning, and global performance.

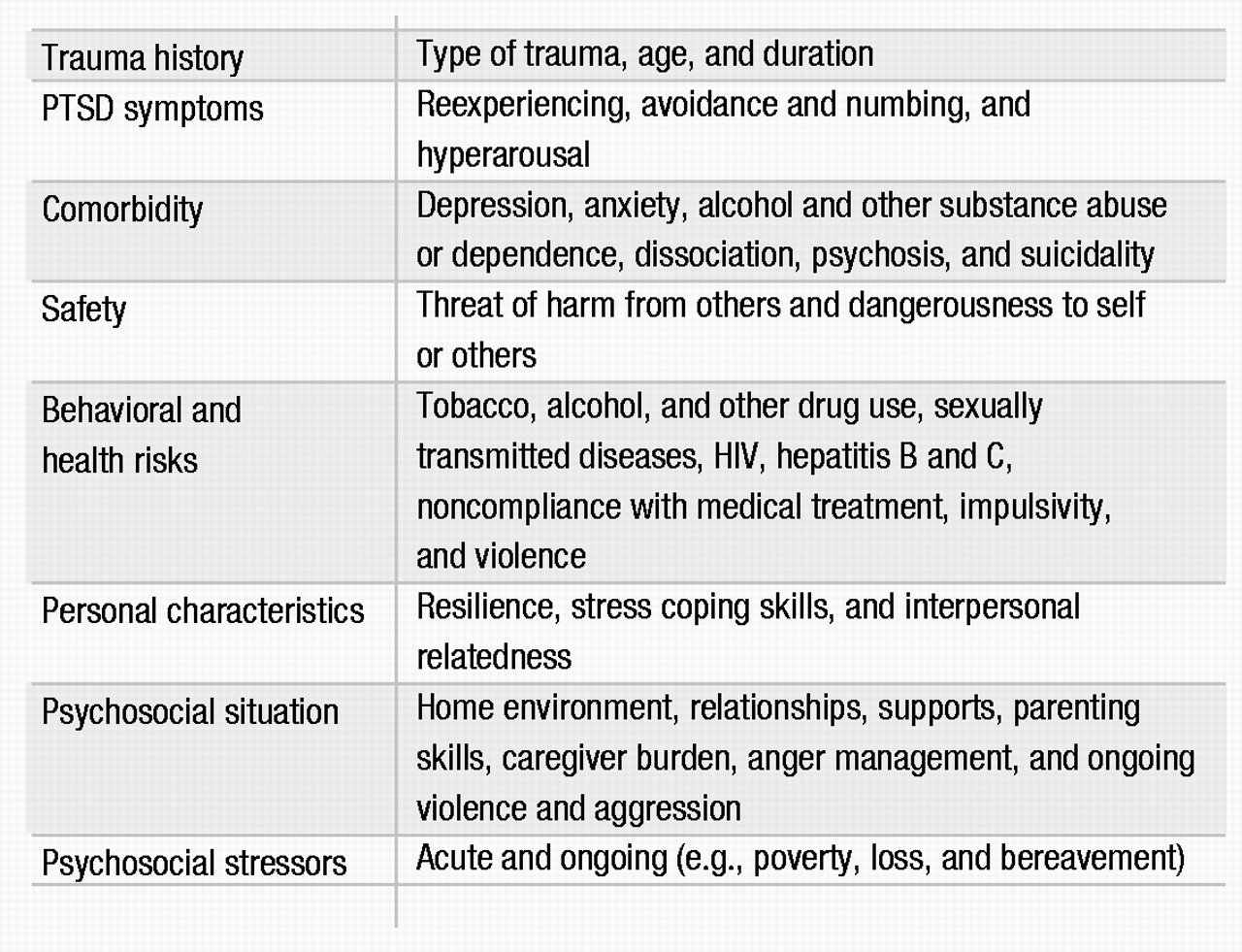

Other clinically relevant domains to be considered in a PTSD assessment are listed in Table 2. The effects of PTSD carry over to other areas of functioning, with high rates of comorbidity and symptom overlap. The presence of comorbid disorders affects both diagnosis and treatment and needs to be identified early in the assessment. Patient safety is a crucial concern. Clinicians should evaluate the threat of harm by others to the patient and family members, such as in the setting of incest or domestic violence. Dangerousness to self and others should also be evaluated, given the risk of aggression, impulsivity, and suicidal behavior in this population (

41,

135). Psychosocial influences and high-risk health behaviors can have a significant impact on current and long-term functioning and also need to be considered. A thorough evaluation of social supports is extremely important, because the presence of supports is a predictor of better outcome (

136,

137). It is also important to place the assessment in the context of acute and ongoing stressors in the individual’s life. Compared with other anxiety disorders, PTSD is associated with lower levels of stress coping (unpublished 2002 study by K. M. Connor and J. R. T. Davidson), which may compromise a person’s ability to handle the stresses of daily life.

Treatment

In treating patients with PTSD, five goals should be considered: reducing the severity of the core symptoms of the disorder, strengthening resilience and coping, reducing comorbidity, reducing disability, and improving quality of life. Research on treatment of PTSD has yielded promising results for both pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions. The issue of combined medication and psychosocial treatment modalities, however, remains largely unstudied.

Pharmacotherapy

With these treatment goals in mind, a variety of pharmacologic agents can be effective for PTSD (Table 3). The SSRIs are considered first-line pharmacotherapy on the basis of data from randomized controlled trials and side effect profiles. The tricyclic antidepressants and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are also effective, although they are less well tolerated and more difficult to prescribe because of side effects, required dietary restrictions to prevent hypertensive crises, and potential lethality in overdose. Although benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, adrenergic agents, and atypical antipsychotics may have a role in treating certain symptoms, there is a lack of controlled trial data supporting their use in this capacity.

SSRIs.

Evidence from several large randomized, double-blind controlled trials indicate that SSRIs are the first line of treatment for both men and women (

92,

138–

143). In these trials, fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine were all shown to have efficacy in reducing the severity of the core symptoms of PTSD and improving quality of life. Study subjects were predominantly women with chronic PTSD related to assault or rape. The trials were of relatively short duration (8–12 weeks), particularly given the chronicity of the disorder. Reductions in the severity of core PTSD symptoms are usually seen within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment; for anger/irritability symptoms improvement may been seen as early as the first week (

144). Relapse prevention trials of 6–9 months’ duration suggest that continued treatment with SSRIs can prevent relapse and provide further improvement in PTSD symptoms, comorbid depression, and quality of life (

139,

145).

There may be differences in core symptom response for the various SSRIs. For example, fluoxetine rendered marked improvement in arousal and numbing symptoms and was more effective in women than in men in two of three studies (

142,

143,

146). In one large, multicenter controlled trial of sertraline, improvement was found in avoidance/numbing and arousal symptoms, but not for reexperiencing, with a more robust overall response noted in women (

147). Subsequent multicenter controlled trials, however, demonstrated efficacy for sertraline and paroxetine for all three symptom clusters in both genders, and both drugs received FDA approval for the treatment of PTSD.

Fluvoxamine was studied in two small open-label trials with outpatients with combat-related PTSD (

148,

149). Preliminary results suggest possible efficacy for sleep-related symptoms, including nightmares.

Tricyclics and MAOIs.

Early trials of tricyclic antidepressants and MAOIs were conducted primarily with male combat veterans, and results suggested efficacy for PTSD. Among the tricyclics, amitriptyline and imipramine demonstrated efficacy in reducing core PTSD symptoms (

150,

151), but desipramine did not (

152). To our knowledge, there have been no controlled trials of tricyclics in women with PTSD. Given the evidence for noradrenergic dysregulation in PTSD and the poor response of some patients to SSRIs, such research is warranted. Studies of MAOIs have suggested efficacy for phenelzine (

150,

153) and possibly brofaromine (a reversible MAOI available in Europe) (

154,

155).

Other antidepressants.

Findings from recent studies have suggested that mirtazapine, trazodone, nefazodone, and venlafaxine may have a role in PTSD treatment. Mirtazapine, a novel drug with both noradrenergic and serotonergic properties, demonstrated efficacy in an open-label study and one 8-week controlled trial (

156,

157). Preliminary data from a small open-label study suggest that trazodone may be effective in reducing the core PTSD symptoms in combat veterans (

158). Of more than 100 patients with chronic PTSD enrolled in six open-label trials of nefazodone, nearly half reported some improvement in symptoms (

159). Two controlled trials with nefazodone were completed, although to our knowledge the results have not been published. Evidence from case reports and case series suggests that venlafaxine also may be effective in the treatment of PTSD, and multicenter controlled trials are under way (

160,

161).

Benzodiazepines.

Benzodiazepines can reduce anxiety and improve sleep but may also increase the likelihood of subsequent PTSD. Their use as monotherapy in this condition should therefore be considered controversial. In an open-label study, temazepam improved insomnia and PTSD symptoms over 5 nights in four subjects with acute stress reactions (

162). Another study prospectively evaluated the effect of acute administration of benzodiazepines (clonazepam or alprazolam) on the course of PTSD in 13 trauma survivors compared with pair-matched controls. Early administration of benzodiazepines was not found have a beneficial effect at 1- or 6-month follow-up assessments and was actually associated with a higher incidence of PTSD (

163).

The addictive potential of the benzodiazepines may be problematic, given high rates of comorbid substance use disorders in PTSD. However, in a recent naturalistic study of over 300 veterans with PTSD and comorbid substance abuse, treatment with benzodiazepines was not associated with adverse effects on outcome (

164). In contrast, a case series of combat veterans with PTSD reported that discontinuation of alprazolam resulted in severe withdrawal and worsening of PTSD symptoms, including rage reactions, nightmares, and homicidal ideation (

165).

Mood stabilizers.

An interest in the therapeutic role of anticonvulsants developed from the recognition of the possible role of neuronal sensitization and kindling in the pathophysiology of PTSD, along with the high prevalence of impulsivity among those with the disorder. Findings from open-label studies of carbamazepine, divalproex, and topiramate and a controlled trial of lamotri-gine demonstrated mixed effects on the symptom clusters (

166–

170). The one consistent finding in these studies, however, was a beneficial effect on reexperiencing symptoms. Controlled trials are needed to investigate this observation.

Atypical antipsychotics.

Up to 40% of patients with PTSD may have psychotic symptoms, underscoring the potential therapeutic role for atypical antipsychotics (

40). To date, preliminary studies suggest a potential role for olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone. Olanzapine is the most widely studied drug in this class, and published reports yield mixed results, including a negative controlled trial with a predominantly female veteran cohort, which contrasted with symptom improvement in all clusters in an open-label study of male combat veterans (

171,

172). In a recent controlled trial of adjunctive olanzapine therapy, improvement was noted in PTSD and insomnia symptoms (

173). Quetiapine may hold promise in the treatment of PTSD, as suggested by findings from an open-label trial with veterans with PTSD (

174). A small controlled trial of risperidone in the treatment of chronic combat-related PTSD failed to demonstrate a treatment difference on the primary PTSD outcome measure, but results did support the efficacy of risperidone for treating reexperiencing and global psychotic symptoms (

175). Additional research on atypical antipsychotics in PTSD is warranted.

Adrenergic-inhibiting agents.

The α

2-adrenergic agonists decrease centrally mediated adrenergic activity and thus may alleviate PTSD symptoms. An open-label study of clonidine used in combination with imipramine showed some improvement in chronic PTSD in severely traumatized Cambodian refugees (

176). Centrally acting α

1-adrenergic antagonists are also thought to hold promise in treating PTSD symptoms. Treatment with prazosin is associated with a reduction in nightmares and improvement in PTSD symptoms in combat veterans with PTSD (

177), and a case report suggests that guanfacine may be efficacious for nightmares in children (

178).

The β-adrenergic blockers may reduce PTSD symptoms through a dampening of peripheral autonomic arousal. Despite the indication of β blockers for heightened arousal states, such as performance anxiety, no controlled trials of these agents have been conducted for PTSD. One naturalistic study of over 300 veterans with PTSD found that β blockers were the most frequently prescribed medications (

179). Results from a recent pilot study suggest that propranolol in the immediate posttrauma period may have preventive effects on subsequent development of PTSD (

180). Additional controlled studies are needed to explore this preliminary finding.

Psychosocial interventions

Psychodynamics of trauma.

Trauma dynamics can involve betrayal, abuse of power, and control. Individuals who survive childhood trauma may develop pathological attachments to perpetrators (

181), and this dynamic can become amplified during psychiatric treatment. For example, residual attachment patterns or longings can be transferred onto the treating psychiatrist. Hence, careful attention to patient-provider boundaries is crucial in PTSD treatment. Contemporary trauma theory holds that clinicians should explore the personal meaning of the traumatic event and counter the demoralization that is so central to PTSD. An emphasis on the here and now is useful, as is educating the patient on the psychological features of the disorder itself.

Psychosocial treatments.

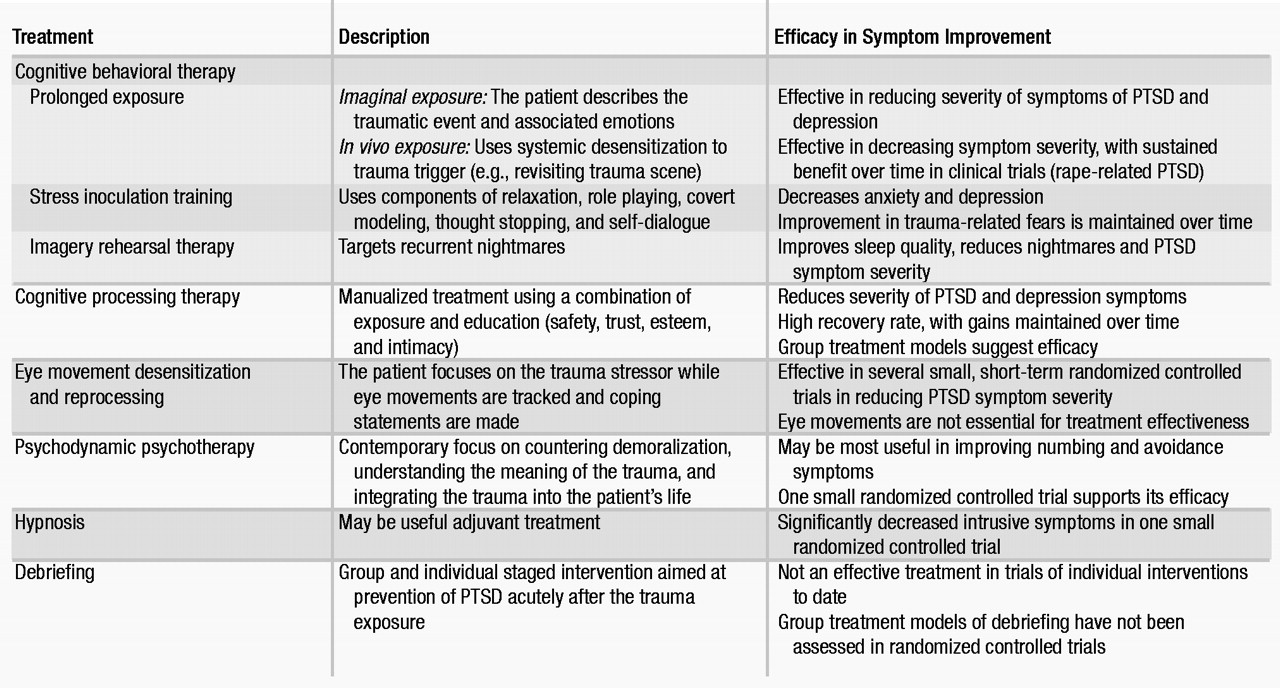

Clinicians providing psychosocial treatments should have special training in PTSD and related psychosocial interventions (Table 4). Cognitive behavioral therapies are the most extensively researched modalities, although most studies have been short-term. Exposure-based therapies and hypnosis techniques may be particularly helpful with intrusive symptoms, whereas cognitive and psychodynamically oriented treatments may be helpful with symptoms of avoidance and numbing. Psychosocial interventions should be tailored to the individual patient, with consideration given to the trauma type, the severity and type of PTSD symptoms, and the related comorbid disorders (

182).

Cognitive behavioral therapies.

The purpose of cognitive behavioral therapy is to correct cognitive distortions and extinguish intrusive traumatic memories. In PTSD, cognitive behavioral therapy targets the distorted cognitions and appraisal process (

183,

184), thereby desensitizing the patient to trauma-related triggers through repeated exposure. Two empirically tested modalities incorporating systematic desensitization are prolonged exposure and stress inoculation training. These treatments are effective in women with PTSD related to assaultive violence or rape. A new cognitive behavioral therapy approach, imagery rehearsal therapy, also shows promise in treating PTSD, particularly associated nightmares and insomnia (

185).

Prolonged exposure was developed for rape-related PTSD in women and is an effective first-line psychosocial treatment, with sustained benefit over time in reducing PTSD symptom severity (

186,

187). This treatment consists of repeated exposure to the trauma and to avoided situations, objects, and memories associated with the trauma. Exposure therapy can be imaginal or in vivo. During imaginal exposure, the patient is instructed to imagine the traumatic event and to describe it aloud with accompanying emotions. In contrast, during in vivo exposure, the patient actually revisits trauma reminders in order to achieve desensitization. Prolonged exposure is effective in decreasing PTSD symptom severity, particularly in the areas of anxiety and avoidance.

Stress inoculation training can be considered a “tool box” for managing anxiety (

187). Techniques include breathing exercises, relaxation training, thought stopping, role playing, and restructuring of distorted thought patterns. Both stress inoculation training and prolonged exposure are effective, alone or in combination, in reducing chronic PTSD symptoms, although prolonged exposure may be superior (

187,

188).

Imagery rehearsal therapy is a brief approach that appears to decrease chronic nightmares, improve sleep quality, and reduce overall PTSD symptom severity. In a controlled trial, rape trauma survivors showed improvement with this treatment, as have crime victims and veterans in open-label pharmacotherapy studies (

185,

189).

Cognitive processing therapy.

Cognitive processing therapy was also developed for PTSD related to rape trauma (

190,

191). It is designed to help correct maladaptive cognitions related to issues such as safety, with emphasis on a written narrative of the trauma. Good outcomes in a group setting format have been reported (

190).

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) (

192–

194) is an exposure-based therapy that combines eye movements, trauma, memory recall, and verbalization. EMDR appears to be as effective as other exposure-based therapies, but the eye movement component of the treatment may be unnecessary (

192,

193). Most EMDR studies have been small, with variable methodological quality and outcomes.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Psychodynamic therapy for PTSD is underresearched, but it is probably efficacious (

195). Only one controlled trial has evaluated psychodynamic therapy in comparison with other psychosocial treatments (trauma desensitization or hypnotherapy) and a control group (

196). In this trial, all three psychosocial treatments were significantly more effective than the control treatment in improving PTSD symptoms of intrusion and avoidance. Although psychodynamic therapy had the least total effect on these symptoms when compared with the other two active treatments, follow-up data showed that the psychodynamic treatment group had the greatest improvement after treatment.

Hypnosis.

The literature on hypnosis in PTSD consists largely of case studies. One small controlled trial found that hypnosis and desensitization significantly decreased intrusive symptoms in PTSD (

196). Hypnosis may best serve in an adjuvant role with other psychosocial interventions.

Psychological debriefing.

Psychological debriefing was developed to prevent PTSD after traumatic stress exposure. However, at present there is no evidence that it is effective for this purpose (

197,

198). Psychological debriefing is a staged, semistructured intervention that addresses both facts and feelings related to the trauma. It also employs psychoeducation to help normalize the patient’s reaction to the trauma and to help foster coping skills and disengagement. Some trauma survivors have reported that group debriefing modalities were helpful (

199), but other reports note that psychological debriefing may be harmful (

198).

Future directions

In the past decade, important advances have been made in our understanding of the epidemiology of trauma reactions, the immediate and long-term neurobiological and psychological responses to traumatic stress, and the impact of pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments in PTSD. These developments, however, represent the early stages in our understanding of the human response to traumatic stress. Among the many directions for future investigation are the topics discussed below.

Acute stress reactions and early posttrauma treatment.

Treatment for acute stress reactions aims to reduce current distress and to prevent stress disorders. Findings from several small controlled trials support the efficacy of cognitive behavioral approaches used in this way (

200,

201), but data from controlled studies for pharmacologic interventions are lacking. Two recent small controlled pilot studies suggest that early posttrauma treatment with propranolol (

180) or imipramine (

202) may be beneficial in reducing posttraumatic symptoms, whereas acute treatment with benzodiazepines may increase the likelihood of subsequent development of PTSD (

162,

163). It is possible that acute intervention may alter the putative disease process, and studies are needed to evaluate potential neurobiological changes associated with acute treatment and to establish the long-term effects of these interventions.

Diagnosis and treatment of partial PTSD.

Many traumatized persons develop subsyndromal PTSD, often meeting criteria for reexperiencing and hyperarousal but not the avoidance/numbing requirement (

20,

203). Although these individuals are less impaired than those with full PTSD, their condition is associated with significant psychosocial impairment (

5,

20,

204). This raises the question of the diagnostic accuracy of the current threshold for PTSD and hence whether we are failing to identify individuals with clinically significant symptoms who might benefit from treatment. Further investigation is needed to understand the place of partial PTSD in the spectrum of pathological stress reactions.

Resilience and PTSD.

Resilience is one of the determining factors in an individual’s ability to deal with stress, yet it remains a neglected aspect of clinical therapeutics. Resilience has particular relevance to PTSD, because this disorder compromises stress coping capabilities, frequently leaving those with the disorder feeling more vulnerable to the effects of daily stress (unpublished 2002 study by K. M. Connor and J. R. T. Davidson) and, in some cases, with a greater susceptibility to developing PTSD from subsequent traumas than those who have not been previously exposed (

205,

206). Little is known about the multifactorial determinants of resilience and the relationship of resilience to PTSD: is impaired resilience a risk factor for PTSD or a consequence of the disorder? Recent evidence, however, indicates that resilience is modifiable with treatment, and this suggests that perhaps resilience may be viewed as another target of intervention (

142).

Ethnocultural considerations.

Cultural distinctions occur in the perception and interpretation of traumatic experiences, the expression of the response to the event, the cultural context of the response by the victim and his or her community, and the path to recovery. These differences create tremendous challenges in cross-cultural research on PTSD. Other impediments to research in this field include ethnocentrism, conceptual equivalence (e.g., linguistic, metric, and functional), the chaos that accompanies mass trauma, and the economics of multinational research efforts. Studies are needed to help further our understanding of the boundaries of PTSD and trauma by exploring differences across cultures.