Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Inappropriate Behaviors in Dementia: A Review, Summary, and Critique

Abstract

The underlying assumptions and the importance of nonpharmacologic interventions

Unmet needs.

Learning/behavioral models.

Environmental vulnerability/reduced stress-threshold model.

Advantages of nonpharmacologic interventions

Literature survey of efficacy of nonpharmacologic interventions

Methods

Search results

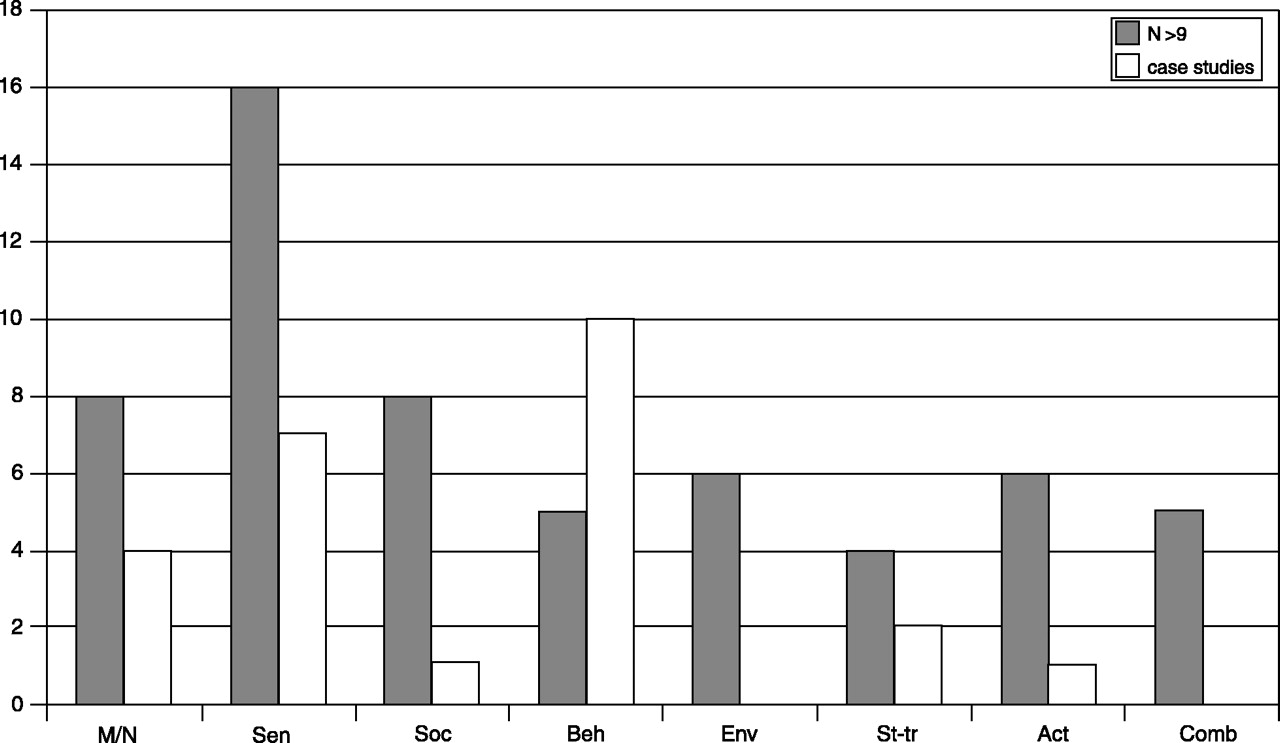

Research studies characteristics.

Treatment efficacy.

Sensory enhancement/relaxation methods

Massage/Touch.

Music.

White noise.

Sensory stimulation.

Social contact: real or simulated

Pet therapy.

One-on-one interaction.

Simulated interaction.

Behavioral interventions

Staff training

Structured activities

Outdoor walks.

Environmental design

Access to an outdoor area.

Natural environments.

Reduced-stimulation units.

Medical/nursing interventions

Bright-light therapy and sleep interventions.

Restraint removal.

Pain management.

Hearing aids.

Combination interventions

Individualization of treatment

Comparison across treatments

Discussion

The nature of the interventions: the interconnections between domains of functioning

The relationship between pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions

Limitations of existing knowledge

Methodological issues limiting the understanding of efficacy: diverse measurement methods.

Criteria for success.

Screening procedures.

Control procedures.

Treatment of failures.

The relationship between target symptom and type of intervention

Intrinsic and conceptual issues limiting the understanding of efficacy

Variation of treatment parameters.

The active ingredient in the intervention.

Effectiveness and implementation in practice

Reasons for limitations in available research

Inherent barriers: participants’ limitations.

System and caregiver barriers.

External limitations.

Recommendations: future directions

| Reference | Subjects | Intervention | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory Enhancement/Relaxation | |||

| I. Massage/Touch | |||

| Kilstoff and Chenoweth (61) | N = 16; NHR; clients of a multi-cultural daycare center in Australia | Gentle hand treatment with three essential oils for 10–15 min. | Analysis of family carers recording showed a decrease of over 20% in wandering and agitation/anxiety |

| Kim and Buschmann (56) | N = 30; NHR; mean age = 76.58 | Hand massage of each hand for 2.5 min., with verbalization | Sig. decrease on E-BEHAVE-AD during treatment time |

| Rowe and Alfred (62) | N = 14; mean age = 76.77 (68–90), residing in the community | Slow-stroke massage for 5 days | Trend (NS) toward reduction of agitation (BSRS) |

| Scherder et al. (57) | N = 16; mean age, 85.7 (78–92), residing in a private residence | Massage (rubbing, brushing, kneading, mostly on the back) | No sig. reduction in aggressiveness (BOP) |

| Snyder et al. (55) | N = 26; AUR; age 60–97 | Nurses administered hand massages to residents before care activity | Sig. decrease during the morning only |

| Snyder et al. (59) | N = 18; AUR; mean age = 77.7 (66–90) | Hand massage, therapeutic touch, administered for 10 days each in the afternoon; (presence used as control condition) | No effect on targeted agitated behavior; sig. effect on anxious (fidgety) behaviors for 3 of the 4- to 5-day Intervention periods (not for Presence/Control). |

| II. Music (during meals, bathing, general) | |||

| Denney (11) | N = 9; NHR; (MMSE: 0–5) mean age = 74.8 | “Quiet music” during lunchtime | Sig. decrease in agitation (CMAI-GA) |

| Goddaer and Abraham (12) | N = 29; NHR; mean age = 81.3 (67–93) | Relaxing music during lunchtime | Sig. decrease in overall agitation (CMAI-GA); no sig. difference in aggressive behaviors |

| Ragneskog et al. (13) | N = 5; NHR; mean age = 80 (69–94) | Music (soothing, ’20s and ’30s pop) played during dinnertime | No effect |

| Clark et al. (9) | N = 18; NHR; mean age = 82 (55–95) | Music during bathing; total of 20 bathing episodes (10 treatment; 10 control) | Sig. decrease in total number of behaviors and hitting behavior |

| Thomas et al. (10) | N = 14; NHR; ages 69–86 | Individualized music played before and during bathing | Sig. reduced aggressive behavior (CMAI-a) during music time |

| Brotons and Pickett-Cooper (18) | N = 30 in 4 NH; mean age = 82 (70–96) | Music therapy twice per week for 30 min. (singing, playing instruments, music game) | Sig. reduced agitation (DBRS) during music therapy sessions and after music therapy |

| Cohen-Mansfield and Werner (14) | N = 32; NHR; mean age = 87.8, 97% with dementia | 1: videotape of a family member talking to elderly person 2: one-to-one social interaction with research assistant (RA) 3: individualized music tapes, 30 min. | Greatest decrease of VDB during one-to-one interaction, followed by exposure to family video, and then music |

| Gerdner (63) | N = 39; mean age = 82 years, in a long-term care facility | Individualized music and classical “relaxation” music | Sig. decrease in agitation during individualized music (vs. classical); Sig. decrease during classical music after 20 min. of intervention |

| Tabloski et al. (17) | N = 20; NHR; mean age = 78.4 (68–74) | Listening to soft music with head-phones for 15 min. | Sig. decrease in agitation (ABS) from 24.15 to a mean of 18.45 during intervention |

| Casby and Holm (64) | 1: 87-year-old woman, verbally agitated 2: 77-year-old, verbally agitated 3: 69-year-old man, verbally agitated | A: No intervention B: Relaxing classical music C: Favorite music | Decrease in vocalizations during intervention phase |

| Gerdner and Swanson (16) | 1: 89-year-old woman; MMSE: 0 2: 87-year-old woman; MMSE: 7; exhibiting pacing/wandering 3: 87-year-old woman; MMSE: 5 4: 94-year-old woman; MMSE: 0 | Individually selected music presented on an audio cassette player | 1: Trend in decrease of agitation (CMAI-a) and continued after the intervention 2: Decreased agitation on 4 out of 5 days 3: Decreased agitation 4: Decreased agitation |

| III. White Noise | |||

| Burgio et al. (19) | N = 13; NHR; mean age = 83.08 (67–99); MMSE: 1.66; verbally agitated | “White noise” audiotapes (environmental sounds) | Sig. decrease (23%) in the 9 responders; (treatment tapes were used in only 51% of the observations) |

| Young et al. (20) | N = 8; mean age = 70 (60–82); wandering behavior in a geriatric hospital | Modified white noise (slow surf rate) at bedside | No effect overall; two patients individually analyzed showed improvement |

| IV. Sensory Stimulation | |||

| Holtkamp et al. (65) | N = 17; NHR | Activities in the “snoezelen” room | Decrease of behavioral problems in residents with “snoezelen” activities |

| Witucki and Twibell (66) | N = 15; mean age = 81.13 (60–95); MMSE: 0-2, in a long-term care facility | Sensory stimulation (music, touch, smell) | Sig. decrease in DS-DAT, particularly in fidgety body language, with each of the sensory stimulation types |

| Snyder and Olson (67) | N = 5; NHR; mean age = 92 | Hand massage or music, each for 10 days | Trend toward decrease in aggressive behavior in each |

| Brooker et al. (68) | N = 4; NHR; ages: 74, 77, 79, 91 | Aromatherapy and/or massage for 10 sessions | Clinical staff impression of benefit to all, but observational data and comparison to control condition show benefit for 2, and sig. decrease in only 1 participant; no advantage of combining massage and aromatherapy; 2 participants manifested increased agitation during treatment |

| Social Contact: Real or Simulated | |||

| I. Pets | |||

| Churchill et al. (23) | N = 28; AUR; mean age = 83.3 | Certified therapy dog for two 30-min. sessions | Sig. decrease in agitation (ABMI) with the dog present |

| Fritz et al. (24) | N = 64; mean age = 74.6 (53–92), in a private residence | Companion animals | Sig. lower prevalence of verbal aggression and anxiety in pet-exposed patients |

| Zisselman et al. (22) | n = 33, pets intervention; N = 58 total; only 22% w/ dementia, in a hospital | 5 days for 1 hour; pets (dog) | Trend (NS) decrease in irritable behavior (MOSES); no sig. difference between pet and exercise |

| II. One-to-One Interaction | |||

| Cohen-Mansfield and Werner (41) | N = 41; NHR; verbally agitated | One-on-one social interaction with research assistants (RAs) | Decrease in verbal agitation (five did not complete 10 sessions) |

| Runci et al. (25) | 81-year-old verbally agitated woman in a long-term care facility | 1: Music therapy with interaction in English 2: Music therapy with interaction in Italian | Italian interaction sig. reduced noisemaking, vs. English interaction |

| III. Simulated Interaction/Family Videos | |||

| Camberg et al. (69) | N = 54; mean age = 82.7; MMSE: 5.1, in a long-term care facility | Simulated presence: interactive audiotape containing one side of a conversation | Sig. decrease in problem behaviors (SCMAI and observations) |

| Hall and Hare (70) | N = 36; NHR; mean age = 76.3 (65–98) | Video Respite™, 21-min.-long interactive videotape of music and reminiscence | No effect |

| Werner et al. (71) | N = 30; NHR; verbally agitated | Family-generated videotapes, 30 min. for 10 consecutive days | 46% (sig.) decrease in disruptive behaviors during videotape exposure |

| Woods and Ashley (72) | N = 27; NHR; age 76–94 | Simulated presence: telephone audio recording of caregiver | Sig. decrease of problem behavior 91% of the time |

| Behavior Therapy | |||

| I. Differential Reinforcement | |||

| Doyle et al. (73) | N = 12 verbally agitated Ss in a long-term care facility | Reinforcement of quiet behavior and environmental stimulation based on individual preferences | Decrease in noise-making (CMAI) in 3 cases; 4 cases w/ no effect (7 of 12 completed study) |

| Heard and Watson (74) | N = 4; NHR; age 79–83; exhibiting wandering | Differential reinforcement = tangible rein-forcers (food) Extinction = attention given in the absence of the behavior | Decrease in wandering (from 50% to 80% reduction) |

| Mishara (7) | N = 80; mean age = 68.8 (±SD 5.1) in a chronic geriatric mental hospital | Token economy: rewards (tokens) for desirable behavior, could then be exchanged for secondary rein-forcers General milieu: all secondary rein-forcers were available for anyone who wanted them; activities were offered for participation but not rewarded | Sig. decreased behavior in general milieu; trend (NS) decrease in token economy |

| Rogers et al. (75) | N = 84; NHR; mean age = 82; mean MMSE: 6.07 | Skill elicitation: identify and elicit retained ADL skills; habit training: reinforce and solidify skills | Sig. decrease in disruptive behavior |

| Birchmore and Clague (76) | 70-year-old female NHR; verbally agitated | Stroking back as reward for quiet behavior | Decrease in vocalizations |

| Boehm et al. (77) | 1: 87-year-old woman 2: 55-year-old man | Behavioral plan that prompted calm, cooperative behavior by rein-forcing (food, toys, and praise) for each small step toward the desired behavior | 1: Decrease of disruptive behavior during bathing 2: Nearly eliminated disruptive behavior during shaving and bathing |

| Lewin and Lundervold (78) | 1: 73-year-old woman, verbally aggressive, in a foster home 2: 76-year-old AU NHR; physically aggressive woman, in a foster home | 1: Communication/problem-solving strategy and provider keeping record of subject’s yelling episodes 2: Implementation of a new routine incompatible with aggression (e.g., supporting herself by holding towel bar) | 1: Yelling behavior stopped, even at 1 month follow-up 2: Sig. decrease in aggressive behavior, but variable |

| II. Stimulus Control | |||

| Chafetz (79) | N = 30; AUR; mean age = 81; exit-seeking | Placement of two-dimensional grid in front of glass exit doors | No effect |

| Hussian (80) | N = 5; mean age = 71.2; inappropriate toileting, bed misidentification, exit-seeking in a long-term care facility | B1: Verbal and /or physical prompts were given to attend to enhancing stimuli (yellow restroom doors) B2: stimulus-enhancement alone | Sig. decrease of problem behavior for each resident |

| Hussian and Brown (81) | N = 8; mean age = 78.5; hazardous ambulation in a public mental hospital | Various two-dimensional grid patterns placed on floor in front of exit door | Sig. decrease of hazardous ambulation; horizontal superior to vertical configuration |

| Mayer and Darby (82) | N = 9; mean age = 77.8; MMSE: ≤12; exhibiting wandering behavior in a psychiatric ward | Mirrors in front of exit doors to prevent exiting | Sig. decrease in successful exiting |

| Bird et al. (83) | 1: 73-year-old woman 2: 62-year-old man with frequent visits to bathroom, residing in a private home 3: 83-year-old woman in a hostel w/anxiety about medication 4: 88-year-old woman, verbally aggressive 5: 83-year-old man; MMSE: 9; urination in corners, residing in a private home | 1: Stimulus control (taught to associate stop sign with stopping and walking away) 2: Stimulus control (beeper signal associated with toileting demand) 3: Spaced retrieval with fading cues 4: Spaced retrieval and fading cues 5: Spaced retrieval; taught to associate cue with location of toilet | 1: Decrease in inappropriate entries (mean of 43.6 to 2) 2: Decrease in anxiety while wearing beeper, but retained fear of soiling himself 3: Decrease in verbal demands for medication 4: No effect 5: Decrease in inappropriate toileting, although prompting needed at night |

| Hussian (84) | N = 3; mean age = 73.4; pacing/wandering in a long-term care facility | First, stimuli (orange arrows, blue circles) were linked to positive and negative consequences (food, loud noise); then, stimuli were placed in areas where participants were encouraged or discouraged to walk, respectively | Decrease of entries into potentially hazardous areas |

| (Study 2) | N = 3; mean age = 74.67; in a long-term care facility | Trained to respond to two stimuli differently; attention to desirable stimulus resulted in reinforcement | Differential reinforcement with stimulus control resulted in reduction of behavior |

| (Study 3) | 64-year-old male NHR; genital exposure and masturbation in lounge areas | 1 = rules; 2 = differential reinforcement; 3 = 2+ antecedent enhancement | Decrease in inappropriate behavior in public area and continued at follow-up |

| III. Cognitive | |||

| Hanley et al. (26) | N = 57, in a psychogeriatric hospital and home for elderly | Reality-orientation (RO): cognitive retraining where orientation information is rehearsed | No effect with RO class (GRS) |

| Staff Training | |||

| Cohen-Mansfield et al. (33) | All NHR in the participating units | In-service training for nursing staff | No effect |

| Matteson et al. (32) | Original sample: n = 63, in a VA nursing home, for treatment group; N = 30, in a community nursing home, for control; mean age = 77; mean MMSE: 12.5; Completers: 43 Treatment, 14 Control | Staff training based on adapting ADL activities to resident’s level on Piaget’s stages; also, environmental modification included cues of colors, symbols, pictures, music, etc.; psychotropic drug withdrawal was also undertaken | No sig. decrease from pre-test to 3 mo., but sig. decreases to 12 and 18 months post-test (NHBPS) for treatment group; control group decreased at 3 and 12 months, but increased to pre-test level at 18 months |

| McCallion et al. (30) | N = 105; NHR | Nursing Aides Communication Skills Program (NACSP) | Sig. reduction in agitated behavior (MOSES and CMAI) for at least 3 months |

| Mentes and Ferrario (28) | N = 8; NHR; physically aggressive | Calming Aggressive Reactions in the Elderly (C.A.R.E.): education program for nurse aides | Decrease in agitation from 11 to 9 incidents of staff abuse after the intervention |

| Wells et al. (31) | N = 40; NHR | Educational program on delivering activities; focused monitoring care | Decreased level of agitation (MIBM and PAS) |

| Williams et al. (29) | N = 2; residents of VA special-care unit responsible for many staff injuries | Staff training in small groups, including empathy training, theory training, and skill training | Sig. decrease, from 0.19 to 0.04 incidents per day, according to patient record review |

| Structured Activities | |||

| I. Structured Activities | |||

| Aronstein et al. (34) | N = 15; NHR; mean age = 81 (68–94) | Recreational interventions (manipulatives, nurturing, sorting, sewing, and music) | Decrease in agitation (CMAI) 57% of the time |

| Groene (53) | N = 30; mean age = 77.5 (60–91); pacing/wandering in an Alzheimer unit | Mostly music (playing instruments, singing, dancing) or mostly reading for 7 days | Decreased wandering in music sessions vs. reading sessions |

| Sival et al. (35) | 1: 76-year-old, verbally aggressive woman 2: 82-year-old, physically agitated woman 3: 81-year-old man All in private residences | Activities program outside their units (musical activities, social activities, games, creative works, singing) | Inconclusive (SDAS-9) |

| II. Outdoor Walks | |||

| Cohen-Mansfield and Werner (37) | N = 12; NHR | Escorting residents to an outdoor garden (one-to-one supervision) | Sig. decrease in physically aggressive and nonaggressive behaviors (CMAI) |

| Holmberg (85) | N = 11; NHR; wandering and physically aggressive agitation | Group walk through common areas or outside, singing and holding hands | Sig. decrease in agitation on group days vs. non-group days |

| III. Physical Activities | |||

| Buettner et al. (54) | N = 36; NHR; mean age: 82.4; MMSE: 6.5 | Sensorimotor program to improve strength and flexibility vs. a traditional program | Decreased agitation during the sensorimotor vs. the traditional program |

| Zisselman et al. (22) | n = 25 in exercise group; N = 58 total in a hospital; only 22% had dementia | Exercise 5 days for 1 hour | NS trend of decrease in agitation (MOSES) |

| Environmental Interventions | |||

| I. Wandering Areas | |||

| McMinn and Hinton (38) | N = 13 participants in a psychiatric facility | Released from mandatory confinement indoors | Decrease in verbal and physical aggression, especially among men |

| Namazi and Johnson (39) | N = 22; AUR; mean age = 80 (69–98) | Unlocking exit door to outside walking paths | Decrease in agitated behaviors (CMAI and DBDS) when door was unlocked |

| II. Natural/Enhanced Environments | |||

| Cohen-Mansfield and Werner (41) | N = 27; NHR; mean age = 84.4 (75–93) | Enhanced environment (corridors decorated to depict nature and/or family environment) | Decrease in most types of agitation (CMAI) vs. No Scenes |

| Whall et al. (40) | N = 31 in five NH | Natural environment (e.g., bird sounds, pictures, food) during bathing | Sig. decrease from baseline to T1 and T2 and in treatment group vs. control (CMAI-W) |

| III. Reduced Stimulation | |||

| Cleary et al. (86) | N = 11; NHR; mean age = 87.2 (81–94) | Reduced Stimulation Unit | Decrease in agitation from 1.7 to 0.8 (4-point scale) |

| Meyer et al. (42) | N = 11, residing in an Alzheimer’s boarding home | Quiet Week, including no TV/radio; staff used quiet voices and reduced fast movements | Sig. decrease in non-calm behaviors |

| Medical/Nursing Care Interventions | |||

| I. Light Therapy/Sleep | |||

| Koss and Gilmore (44) | N = 18; NHR | Increased light intensity during dinnertime | Sig. decrease in agitated behaviors |

| Lovell et al. (87) | N = 6; NHR; mean age = 89.2 | Bright light (2,500 Lx) in the morning for 10 days | Sig. decrease in agitation (ABRS) |

| Lyketsos et al. (88) | N = 15, in a chronic care facility | Bright-light therapy | No effect (BEHAVE-AD) vs. a control group |

| Mishima et al. (89) | N = 24; mean age = 75 in an acute-care hospital | Morning-light therapy | Sig. decrease in problem behaviors from an average of 23.9 to 11.6; also, an increase in nocturnal sleep |

| Okawa et al. (90) | N = 24; mean age = 76.6; n = 8 (controls), in a geriatric ward w/sleep-wake disorders | Phototherapy with illumination of 3,000 lux in the morning | Effective for sleep-wake rhythm disorder in 50%; behavioral disorders decreased |

| Satlin et al. (91) | N = 10; mean age = 70.1, in a VA hospital, with sundowning (MMSE: 0.6) | 2-hour exposure to light (1,500–2,000 lux) while seated in a gerichair | No effect on agitation, but a decline in severity of sundowning and sleep-wake problem patterns |

| Thorpe et al. (92) | N = 16; ages 60–89 in a long-term care facility | Light administered using the Day-Light Box 1,000 | Trend to decreased agitation (CMAI and EBIC) vs. baseline in posttreatment week |

| Alessi et al. (45) | N = 29; NHR; mean age = 88.3 | Increased daytime activities and a nighttime program to reduce sleep-disruptive noise | 22% decrease in agitation vs. base-line (sig. difference from control group); increase in nighttime sleep from 51.7% to 62.5% vs. controls |

| II. Pain Management | |||

| Douzjian et al. (48) | N = 8; long-term residents of skilled nursing facility; >70 years old | 650 mg acetaminophen t.i.d. | Five residents (63%) showed decrease in behavior measured; four orders for antipsychotic drugs and one for antidepressant drugs successfully discontinued |

| III. Hearing Aids | |||

| Palmer et al. (48) | N = 8; 5 men, 3 women, ages 71–89; MMSE: 5–18; community-dwelling | Hearing aids provided | Decrease in problem behavior as reported by caregiver |

| IV. Removal of Restraints | |||

| Middleton et al. (93) | N = 4; age 69–82, in a long-term care facility | Pain management, restraint management, and beta-blockers | Decrease in the amount and intensity of aggressive behaviors (OAS) |

| Werner et al. (46) | N = 172; NHR, no Restraints: n = 30; mean age: 86.9; Restrained: n = 142; mean age: 86.1 | Educational program for nursing staff, then removal of restraints | Sig. decrease in all types of agitation (SCMAI; only those exhibiting agitation while restrained included for analysis) |

| Combination Therapies | |||

| I. Individualized Treatments | |||

| Hinchliffe et al. (94) | N = 40; mean age = 81 (65–93); MMSE≥8 in the community | Individualized treatments: combination of pharmacologic and non-pharmacological interventions (activities, if understimulated) | Sig. decrease in problem behaviors in first treatment group, but not in the delayed-treatment condition |

| Holm et al. (95) | N = 250; mean age = 81 (SD = 8) in an acute-care hospital | Individualized inpatient program plan; pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic | Sig. decrease in agitation (RAGE); problem behaviors eliminated in 38% of patients |

| Matthews et al. (96) | N = 33; mean age = 84.2 (67–98) in a dementia unit | Client-oriented care, residents’ wishes respected; scheduled events adjusted for individual residents | Sig. decrease in verbal agitation (CMAI) 6–8 weeks after the change |

| II. Intervention Programs | |||

| Rovner et al. (8) | N = 81; NHR; mean age = 81.6 | Activity program (music, exercise crafts, relaxation, reminiscences, word games), reevaluation of psychotropic medication, and educational rounds | Sig. decrease in agitation vs. control group (at 6 months, behavior disorder exhibited by 28.6% vs. 51.3%) |

| Wimo et al. (97) | N = 31; median age = 82 (62–96), residing in a psychogeriatric ward | Program developed including team care, enhanced environment, flexibility in daily routine, evaluations | No effect on irritability; worsening in restlessness vs. controls |

Note: NS = not statistically significant; sig. = statistically significant; SD = standard deviation; S = subject; NHR = nursing home residents; AUR = Alzheimer disease unit residents; NH = nursing home; VDB = verbally disruptive behavior; ABMI = Agitation Behavior Mapping Instrument (1); ABRS = Agitation Behavior Rating Scale (98); ABS = Agitated Behavior Scale (99); BOP = Beoordelingsschaal Voor Oudere Patienten (100); BSRS = Brief Behavior Symptom Rating Scale (101); CMAI = Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (102); CMAI-a = Adaptation of Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (103); CMAI-GA Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (102), as modified by Goddaer and Abraham (12); CMAIW = Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (102), as modified by Chrisman et al. (104); DBDS = Dementia Behavior Disturbance Scale (105); DBRS = Disruptive Behavior Rating Scales (106); DS-DAT = Discomfort Scale for Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type (107); E-BEHAVE-AD adaptation by Auer et al. (108) of the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD) (109); EBIC = Environment Behavior Interaction Code (110); GRS = Geriatric Rating Scale (111); MIBM = Modified Interaction Behaviour Measure (112); MOSES = Multidimensional Observation Scale for Elderly Subjects (113); NHBPS = Nursing Home Behavior Problem Scale (114); OAS = Overt Aggression Scale (115); PAS = Pittsburgh Agitation Scale (116); PGDRS = Psychogeriatric Dependency Rating Scale (117); RAGE = Rating Scale for Aggressive Behavior in the Elderly (118); SCMAI = Short Form of the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (119); SDAS-9 = Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale (120).

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).