Hispanics are linked primarily by a common language derived from Spain as well as by some aspects of ethnic heritage (

10). The U.S. Census Bureau defines Hispanics as persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central and South American, or other Hispanic heritage, with the latter two options functioning as catchall categories for smaller subgroups. In 2002, 66.9% of U.S. Hispanics were Mexican, 8.6% were Puerto Rican, and 3.7% were Cuban (

3). These are the three largest subgroups, and they are the most studied in mental health research (

10).

Hispanics are more geographically concentrated than non-Hispanic whites, with nearly 8 out of 10 living in southern and western states. They also are more likely to live inside the central cities of metropolitan areas and less likely than non-Hispanic whites to live in nonmetropolitan areas (

3). The largest Mexican populations live in California, Texas, Illinois, and Arizona; the largest Puerto Rican populations reside in New York, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania; and the majority of Cuban Americans call Florida home. Perhaps more indicative of future trends are clusters of Hispanics who live in states not historically associated with Hispanic settlement, such as North Carolina, Georgia, and Iowa, representing as much as a quarter of a given county’s population (

11).

Evidence of disease burden

Research on the prevalence of depression among Hispanics provides some perspective on the heterogeneity of the three largest subgroups, and the representation of each group in the literature is roughly proportional to their relative sizes. The largest, most recent study (

12), using data from the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), showed that Mexican Americans generally face a lower risk of depression than do non-Hispanic whites. This conclusion echoes analyses (

13,

14) of data collected in the early 1980s for the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (

15) and the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (H-HANES) (

16). NESARC data also confirm that Mexican immigrants are approximately half as likely as their U.S.-born counterparts to experience mental disorders, as demonstrated earlier with ECA data (

17) and the Mexican American Prevalence and Services Survey (MAPSS) (

18). These earlier studies further concluded that acculturation appears to work against the immigrant advantage; MAPSS data showed that the estimated lifetime mental disorder rate for immigrants who had lived in the United States for more than 13 years was nearly double that for more recent immigrants.

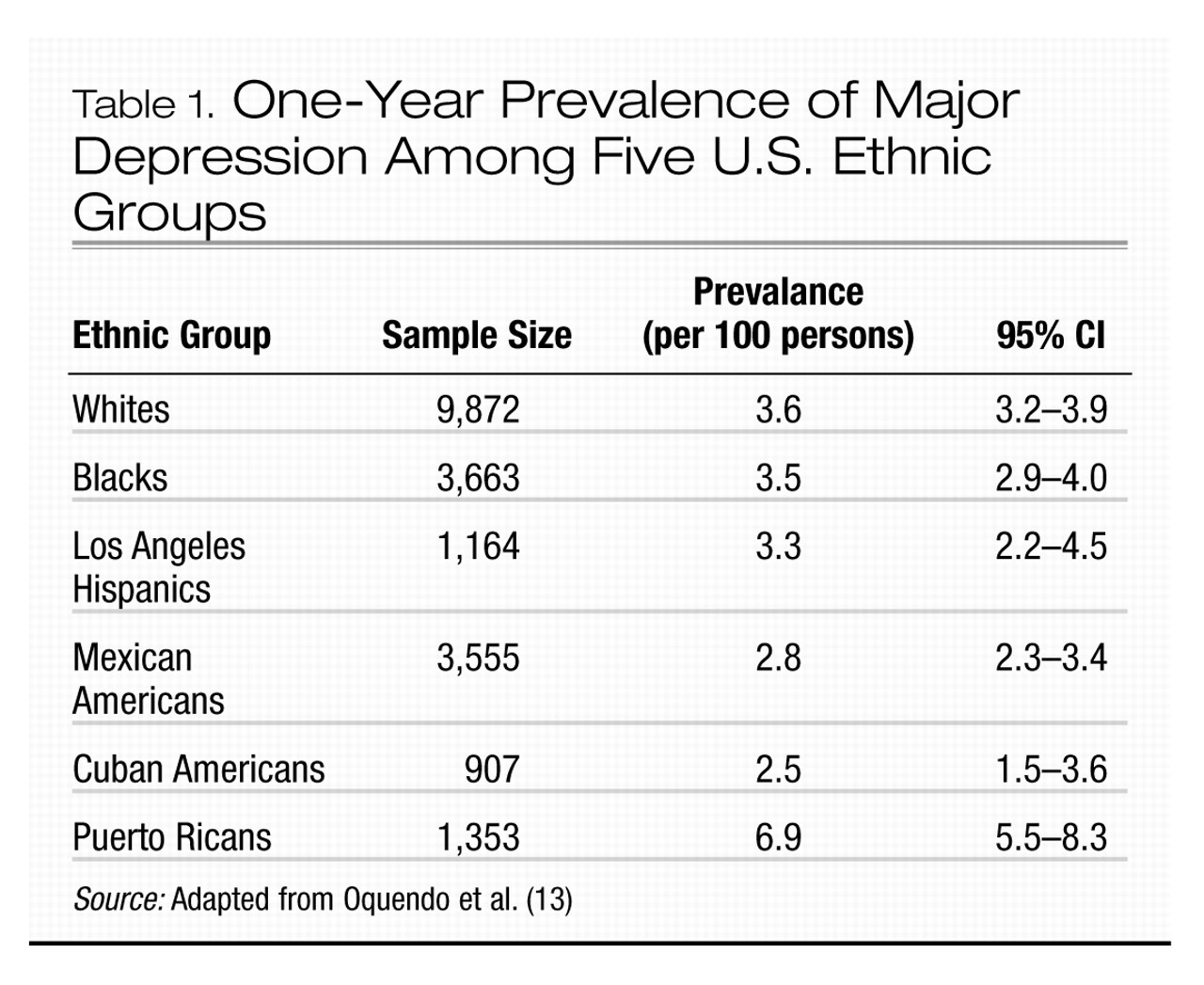

U.S. Puerto Ricans appear to face greater mental health risks, as suggested by data showing current, 6-month, 1-year, and lifetime depression rates more than double those for Mexican Americans and Cuban Americans (

13,

16). Furthermore, Puerto Ricans are almost twice as likely as whites to have depression in a given year (Table 1). The situation is not much better in Puerto Rico, where the proportion of the population experiencing elevated symptoms of depression is similar to that for U.S. Puerto Ricans (

19) and the overall prevalence of mental disorders is similar to that for the general U.S. population (

20). This similarity between island Puerto Ricans and the U.S. population has been attributed to the industrial and economic development of the island and unrestricted circular migration between the mainland and Puerto Rico (

20). Still, there is some evidence of a greater risk of depression in the U.S., such as data suggesting that the lifetime rate of depression for Puerto Ricans in New York City is nearly twice that for island Puerto Ricans (

16,

20).

Mental health data on Cuban Americans are relatively sparse, in part because the ECA study did not include Cuban Americans. Furthermore, a lack of data on mental disorders within Cuba precludes assessment of any potential immigration correlation. The H-HANES reported lifetime, 6-month, and 1-month prevalence rates of major depressive disorder of 3.15%, 2.12%, and 1.5%, respectively, for Cuban Americans, which is comparable to rates for Mexican Americans and less than half the rates for Puerto Ricans (

21).

An evaluation of the depression burden borne by Hispanics also requires consideration of the effects of culture on illness presentation. The acceptability of psychiatric care varies among cultures and depends in part on the ways in which mood disturbances are perceived (

22). Cultures that are less accustomed, willing, or able to consider mood disturbances to be psychiatric disorders are more likely to express them as somatic complaints (

23). Some data have indicated higher rates of somatization among Puerto Ricans (

24) and Mexican American women over the age of 40 years (

25), compared to non-Hispanic whites. Other research (

26) has suggested that structured diagnostic interviews may yield artificially high rates of somatization because of cultural differences in language usage and utilization of care.

Similarly, clinicians need to be cognizant of the disparate folk constructs various ethnic groups hold regarding mental health problems. Many of these, including

susto (fright),

nervios (nerves), and

mal de ojo (evil eye), are listed in the DSM-IV Glossary of Culture-Bound Syndromes, and a number of articles (

27–

31) have characterized these folk syndrome patterns and their overlap with DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic entities. Engaging patients in ways that honor their conceptions of illness is essential to formulating accurate diagnoses and establishing therapeutic alliances.

Research on substance use and suicide prevalence provides additional perspective on the heterogeneity of mental health burden and subpopulations, although coverage of the literature is beyond the scope of this review. Data on these topics were collected in conjunction with NESARC, H-HANES, the ECA study, and the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (

32), and a number of reviews are available. Similarly, literature reviews dedicated to the challenges facing younger and older Hispanics contribute to our understanding of Hispanic mental health across the life cycle.

Potential influences on disease burden

A number of causes and contributing factors have been proposed for the mental health burdens borne by U.S. Hispanics, most of which similarly influence the risks other cultures face. Examples of shared risk factors for depressive symptoms include female gender (

18,

33,

34), low educational achievement (

19,

34–

36), low income (

19,

33–

35), unemployment (

19,

21,

36), and medical comorbidity (

37). In the Hispanic population, the prevalence of some factors is greater. Only 57% of Hispanics age 25 years and older have completed high school, compared with nearly 89% of non-Hispanic whites, and more than one-quarter have less than a ninth-grade education, compared with 4% of non-Hispanic whites. Furthermore, Hispanics are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to live in poverty (21.4% vs. 7.8%) and to be unemployed (8.1% vs. 5.1%) (

3).

Risk factor logic hits a snag, however, in consideration of Mexican American immigrants, who have lower levels of income and education as well as lower rates of depression (

12,

17,

18). This finding is consistent with the “Hispanic paradox” concept that emerged as public health researchers began noting better findings on a number of health measures (e.g., birth weight and mortality from cardiovascular causes) than typically is associated with lower socioeconomic status (

38). The concept has been refined through subsequent research, such as in an analysis of adult mortality data (

39) suggesting that the benefit is limited to immigrant Mexican Americans and other Hispanic immigrants who are not Puerto Rican or Cuban. Additional perspective on demographic risk factors is provided in a study (

33) that found few statistically significant differences in prevalence or severity of depression among whites and ethnic subgroups once results were adjusted for demographic differences such as gender and income.

The act of making a life within a new culture appears to carry its own risks. Marital dysfunction (e.g., divorce and separation) increases in the second and third postimmigration generations (

40,

41) and is associated with a greater risk of depression (

16,

42). Burnam et al. (

17) reviewed ECA data using a multidimensional scale of acculturation and found that U.S.-born Mexican Americans were more acculturated than those born in Mexico. They also suffered from the highest rates of mental disorders of any ECA subgroup, even after age, sex, and marital status were controlled for. Ortega et al. (

43) reached a similar conclusion in an analysis of NCS data. A third study (

44) found a positive correlation between acculturation and risk of depression among younger Mexican Americans (20–30 years of age) but not their older counterparts.

Consideration of the social, economic, and political factors leading to emigration may also help explain variations in mental health burden. Mexican and Puerto Rican emigration has been driven generally by economic need, whereas for Cubans and South and Central Americans, it is more likely related to political dissent and seeking asylum as refugees (

45). Central and South American immigrants in particular may have fled political or war-related trauma that would place them at higher risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (

46). Political refugees also may be more likely to experience a reduction in socioeconomic status and associated distress.

Health services

The inadequacy of mental health care for U.S. Hispanics may be attributed to both patient and system factors. Examples of patient factors undermining access to care include socioeconomic position, language proficiency, and citizenship status. System factors encompass issues related to the delivery and reimbursement of care. Access to care, utilization of care, and quality of care all are in need of improvement for Hispanic populations.

Access to care

Effective care is central to improvement of mental health services, if only because concepts such as utilization and quality of care mean little without it. Moreover, effective access requires that patients be able to navigate the health care system beyond an initial visit or two. This is true particularly for mental health care, for which ongoing treatment is the norm. Thus, access to care should be regarded as the ability to enter the care system plus the ability to receive care on an ongoing basis.

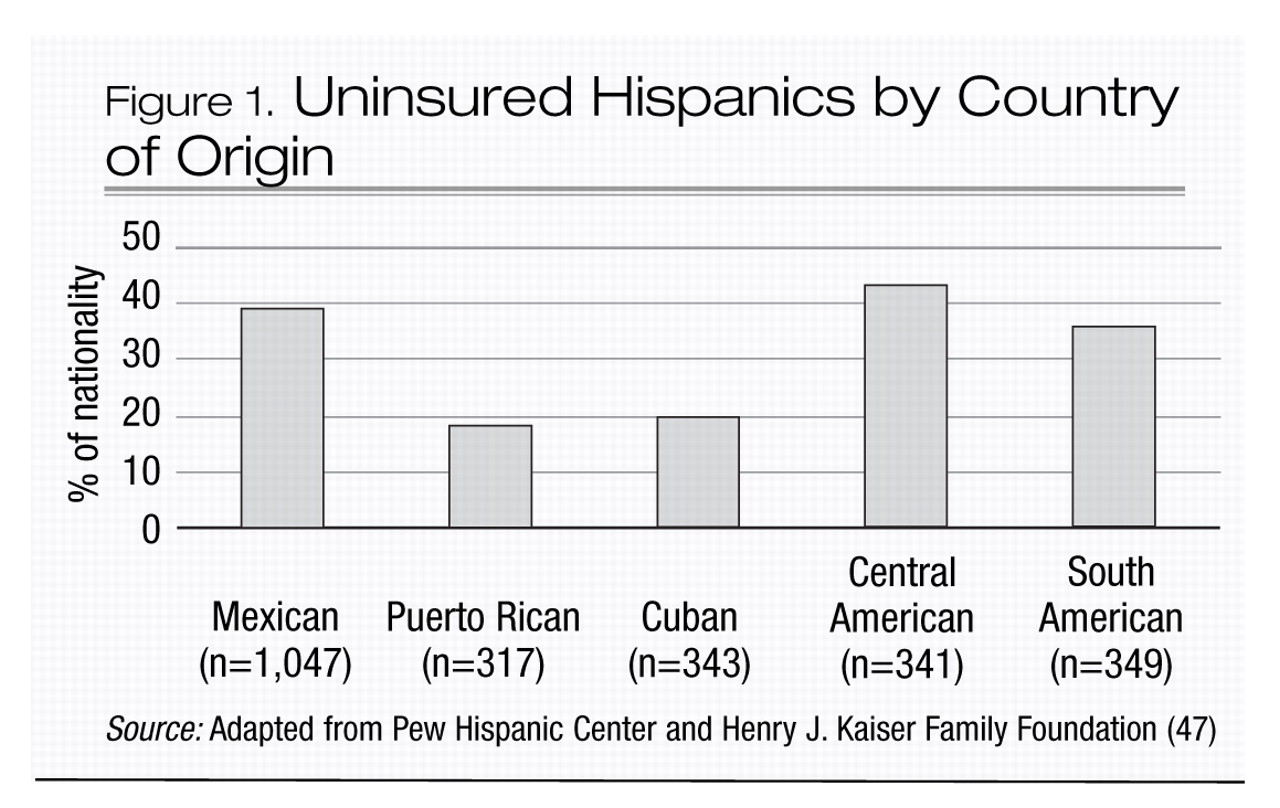

With one in five living in poverty (

3), Hispanics are more likely to live in resource-poor neighborhoods and to have no income available for mental health care. More than one-third lack health insurance, despite the fact that almost two-thirds of the uninsured are employed (

47), which suggests disproportionate employment in occupations that do not offer health care benefits. Moreover, the proportion of Hispanics lacking health insurance has been on the rise (

48,

49), and lack of coverage is the primary reason Hispanics are more likely than whites to report unmet medical needs, not to have a regular health care provider, and not to have seen a physician within the past year (

50). As with other variables discussed here, the likelihood of having insurance coverage varies by national origin (Figure 1) (

47). Puerto Ricans are more likely than Mexican Americans to be insured because their status as U.S. citizens makes them eligible for publicly funded health benefits. Cuban Americans benefit both from refugee status and elevated socioeconomic standing and are more likely to have private insurance (

51,

52).

Although broadly predictive of access to care, disparities in income and health insurance coverage do not account fully for access disparities (

53,

54). A study (

55) of immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican Americans showed that knowing where to find a provider increased the likelihood that a person would seek and use specialty mental health care. Indeed, the U.S. health care system is among the most complex in the world and presents barriers to natives as well. Language is a significant issue (

56), with nearly three of every 10 Hispanics reporting problems communicating with providers (

47). Related to the language barrier is the relative scarcity of U.S. mental health professionals of Hispanic origin. There are approximately 29 Hispanic providers per 100,000 Hispanics, compared with 173 white providers per 100,000 non-Hispanic whites (

57). With fewer culturally proficient professionals, geographic distribution of providers is very likely another issue, particularly for rural Hispanics and the more recently formed Hispanic population clusters. Employment circumstances also may represent a barrier if provider availability during non-work hours is limited. Moreover, even finding non-work hours may be a challenge, as it is not uncommon for Hispanic heads of household to work two or three jobs to provide for their families.

Utilization of care

Additional factors contributing to inadequate mental health care for U.S. Hispanics are evident in utilization patterns. Mexican Americans in the ECA study who had experienced mental disorders within the previous 6 months were only half as likely as whites (11% vs. 22%) to use health or mental health services (

5). Mexican Americans with psychiatric disorders also are more likely to receive care from general medical care providers than mental health specialists, particularly in rural areas (

6). Among Mexican Americans who had a psychiatric disorder in the previous year, the U.S. born are seven times more likely than the foreign born to have seen a psychiatrist (8.8% vs. 1.2%) and three times more likely to have visited any mental health specialist (13.4% vs. 4.0%) (

55).

Fewer data are available to characterize Puerto Ricans and Cuban Americans, among whom utilization of care generally is thought to be higher. Obtaining care may be more ingrained in Puerto Rican culture. In a study of poor island dwellers (

58), 32% of those who met criteria for mental health care need received at least some care within the previous year. Like Mexican Americans, patients in this study were more likely to seek care for mental health in the medical care sector. An expenditures study (

52) demonstrated that Puerto Ricans had the highest annual medical expenses and were more likely to have had at least one physician visit in the previous year, compared with Mexican and Cuban Americans. Greater utilization among Cuban Americans has been attributed to greater access to public care because of refugee status (

51), higher rates of private insurance (

52), and greater familiarity with American-style care delivery (

52,

59).

Lower socioeconomic status has been linked to lower utilization regardless of insurance status (

60,

61). Language barriers probably influence utilization, as evidenced by a study (

62) that found that Hispanics with fair or poor English proficiency had 22% fewer physician visits than non-Hispanics. Similarly, the relative lack of Hispanic providers appears to be a factor. Mexican Americans with ethnically matched therapists have been found to remain in treatment longer and to have better outcomes (

63). Moreover, minority patients characterize their physicians’ decision making as less participatory than do nonminorities (

64), and patients in race-concordant therapeutic relationships rate their visits as significantly more participatory than do those in race-discordant dyads (

65).

Utilization also may be affected by help seeking directed toward other sources. Not only were Mexican Americans who had a psychiatric disorder within the previous year more likely to see a general medical professional (19.9%) than a mental health specialist (9.3%), they also were more likely to see other professionals, including priests, chiropractors, and counselors (11.2%). Patients saw informal sources such as folk healers, spiritualists, and psychics less frequently (4.5%) (

55).

Finally, bias and prejudice probably exert some influence on utilization. After Proposition 187 was passed by California voters, making illegal immigrants ineligible for public health services, use of outpatient mental health services by younger Hispanics dropped by 26% and use of crisis services increased (

66). Health care professionals may unintentionally incorporate bias or stereotypes in the course of assessment or treatment (

67,

68), leading patients to reject treatment recommendations. Patients, too, may have negative attitudes toward mental health care that are based on the experiences of others (

55,

69), resulting in avoidance.

Quality of care

Mental health care for U.S. Hispanics is compromised by lower quality of care. Here again, language represents a significant obstacle, as quality of care depends on the quality of the communication between provider and patient. In medical care settings, language barriers have been associated with less discussion of medication side effects and potentially poorer compliance (

70), reduced question asking and patient recall of clinician encounters (

71), and lower utilization of preventive health screening (

72,

73). Clear communication becomes all the more crucial in mental health care, which requires a shared understanding of subjectively experienced symptoms.

Uncertainty in interpreting disease symptoms in minorities leads to differences in care, a dynamic known as statistical discrimination (

74), which has been shown to affect the diagnosis of depression, hypertension, and diabetes (

75). In a study of pediatric emergency department data (

76), the presence of a language barrier was associated with significantly higher charges related to diagnostic tests. Although expensive diagnostic tests are less likely to be an issue in mental health settings, this finding nevertheless suggests that communication difficulties often leave providers without the information needed for accurate diagnosis.

High utilization of general or family practitioners to address depression-based symptoms is another potential influence on overall quality of care, with some data (

77) suggesting that Hispanics are less likely than whites to obtain mental health diagnoses in the primary care setting. Furthermore, among patients with self-perceived need for treatment for substance use or other mental disorders, most of whom utilized primary care providers, Hispanics were significantly more likely than whites to report less care than needed or delayed care (22.7% vs. 10.7%) (

7). An alternative perspective, however, is provided in a study (

78) suggesting that primary care providers recommend depression treatments equally to Hispanic and white patients but that Hispanics are less likely to take antidepressants and to obtain specialty mental health care.

Still, use of mental health providers does not guarantee higher quality of care, as suggested by data from community health clinics showing that minorities are significantly less likely than nonminorities to receive a treatment recommendation to take an antidepressant (

79). Similarly, a review of National Ambulatory Medical Care data found that minorities were approximately half as likely to have office visits documenting antidepressant therapy, a diagnosis of depressive disorder, or both (

8). In a study comparing psychiatric emergency service diagnoses with those obtained subsequently via structured interview (

80), diagnostic agreement was significantly more likely for white than for nonwhite patients. The diagnostic disagreement was attributable to information variance associated with the patient’s race in nearly 60% of cases. Finally, a large study of psychiatric outpatients (

81) found that Hispanics were approximately 74% more likely than European and African Americans to receive a diagnosis of major depressive disorder and that although Hispanics had the highest level of self-reported psychotic symptoms, African Americans were almost twice as likely to receive a diagnosis from the schizophrenia spectrum of disorders. Among the potential causes of misdiagnosis cited by the authors are cultural variance in the behavioral repertoire (e.g., symptoms that are indicative of psychosis in one culture but more normative in another) and diagnostic bias.