Research has shown that there are important differences in rates of psychiatric disorders between non-Hispanic white populations and members of racial and ethnic minorities in community samples in the United States (

1,

2). The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study showed that African Americans had higher rates of schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, phobia, and substance use disorders and lower rates of affective disorders than whites in the general population; Hispanics had higher rates of affective disorders and lower rates of schizophrenia than whites in the general population (

3). However, after the analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, no significant racial/ethnic group differences were observed, suggesting that lower socioeconomic status and other social disadvantages rather than race/ethnicity may have accounted for the higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders. In contrast, unadjusted and sociodemographic-adjusted results from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) showed that African Americans had lower rates of all psychiatric disorders and that Hispanics had significantly higher rates of current affective disorders (

4).

Studies of preclinic help seeking (

5) indicate that members of ethnic minority groups are less likely to access psychiatric care and have a greater unmet need for care, with less acculturated Hispanics the least likely to seek care (

6). In the early 1980s, African Americans with bipolar disorder were found to be more likely than white Americans to receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia (

7). Data from clinical samples showed that when treated, African Americans were more likely than white Americans to receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia and less likely to receive a diagnosis of depression, and they were more likely to receive care in emergency and inpatient settings (

8). African Americans and Hispanics are more likely than others to seek help in primary care settings than from a psychiatrist or other mental health specialist (

6).

The Surgeon General’s report on culture, race, and ethnicity (

8) showed that while the science base on racial and ethnic minority mental health is inadequate, the best available research indicates that these groups have less access to and availability of care and that they tend to receive poorer quality mental health services. Further research is needed to understand the extent to which sociodemographic and care setting/payment factors explain racial/ethnic differences in psychiatric disorders and the extent to which mental health professionals accurately diagnose mental disorders in members of ethnic minority groups. Understanding the nature of racial/ethnic differences in psychiatric diagnosis is an important step toward improving access to psychiatric treatment and provision of mental health services to ethnic minorities, who will soon become the numeric majority in the United States (

9).

In this study we examined racial and ethnic differences in the diagnostic and clinical characteristics of a large national sample of patients as reported by psychiatrists in routine clinical practice in the United States. We also assessed the extent to which diagnostic and clinical characteristics vary with patients’ racial/ethnic background after adjusting for differences in sociodemographic variables and care setting/payment characteristics.

Method

Data source

Detailed sociodemographic, clinical, diagnostic, treatment, and health plan data on a systematic sample of 3,088 patients were provided by a national sample of 754 psychiatrists who participated in the 1997 and/or 1999 Study of Psychiatric Patients and Treatments. The studies were conducted by the Practice Research Network (PRN), which is a project of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education, an APA affiliate. The PRN psychiatrists are APA members who spend at least 15 hours a week in direct patient care and who agreed to participate in the practice-based research network. The PRN psychiatrists include practicing clinicians who work in the full range of public and private treatment settings in the United States. Approximately half (48%) of the PRN psychiatrists were randomly selected and recruited from the APA membership to ensure representativeness; the remainder were self-selected volunteers recruited nationally by APA and local district branches. Each PRN psychiatrist was randomly assigned a start date and time to complete a 24-item data collection instrument on three randomly selected patients from a patient log. For the 1997 study, 518 PRN members were asked to participate, and 417 (79%) responded, providing clinically detailed data on 1,245 patients. For the 1999 study, 784 psychiatrists were asked to participate, and 615 (78%) responded, providing data on 1,843 patients.

Patient sample

Only patients age 18 or older were included in the sample. The sample included 2,655 patients; 254 were African American (9.5%), 149 were Hispanic (6.3%), and 2,158 were white (84.3%) (percentages are based on weighted data). Because of the small number of Asian/Pacific Islanders (n=35), Native Americans (n=34), and patients of “other” racial/ethnic categories (n=25), these groups were excluded.

Sampling weights

Weights were developed independently for each of the two study years, adjusting for differences between PRN psychiatrists and the APA membership due to oversampling of younger and minority psychiatrists, survey nonresponse, and clustering of multiple patients from the same psychiatrist. Demographic, training, and practice data from the APA membership database and PRN’s 1996 and 1998 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (NSPP) were used in developing weights. Stabilization of weights at each stage of weight development reduced the effect of outliers. The SUDAAN program was used to analyze the weighted data and generate nationally representative estimates (

10,

11).

Measures

Because socioeconomic status and other demographic characteristics have been shown to confound the association between race/ethnicity and patterns of psychiatric disorders (

3–

5), the analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic variables. The analyses were also adjusted for health insurance status and treatment setting, as African Americans are overrepresented in public plans and in inpatient facilities. The analyses also controlled for region of residence, which is associated with race, income, and insurance coverage (

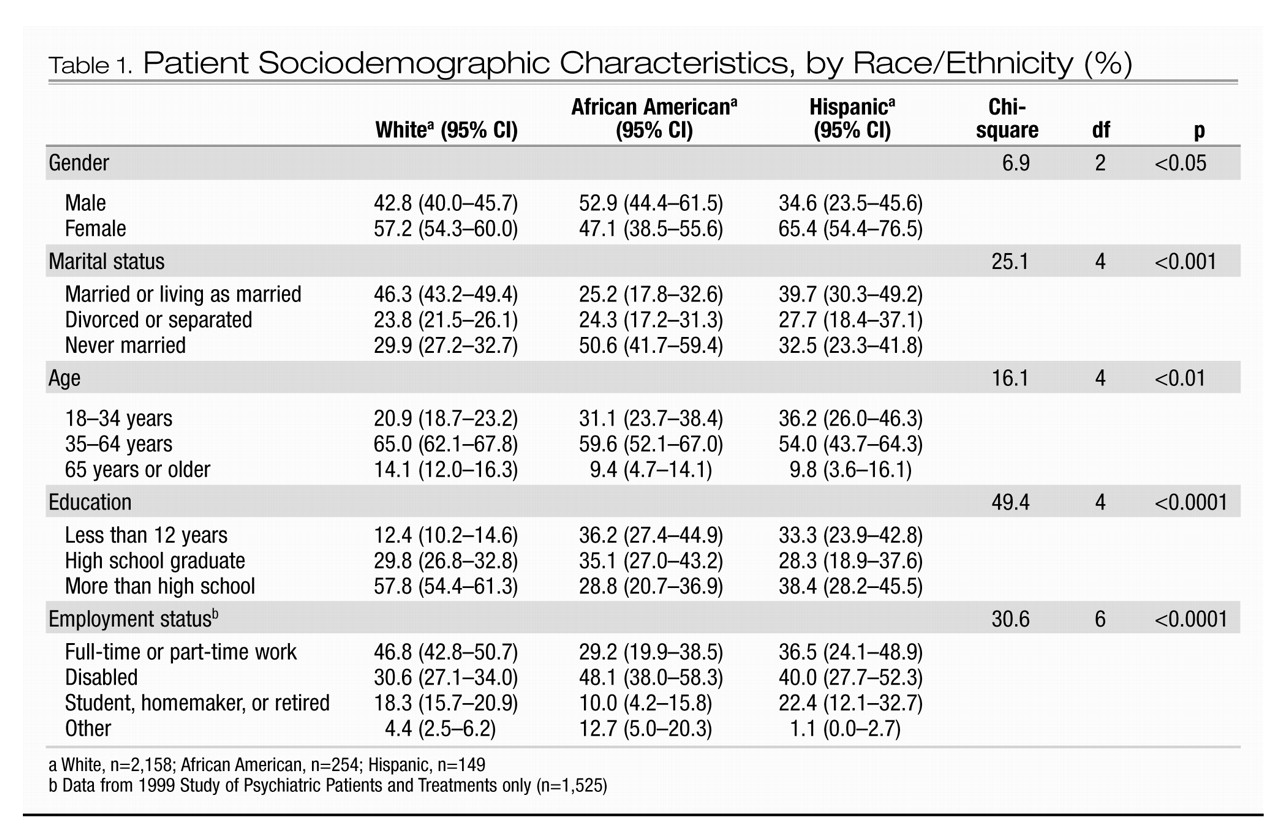

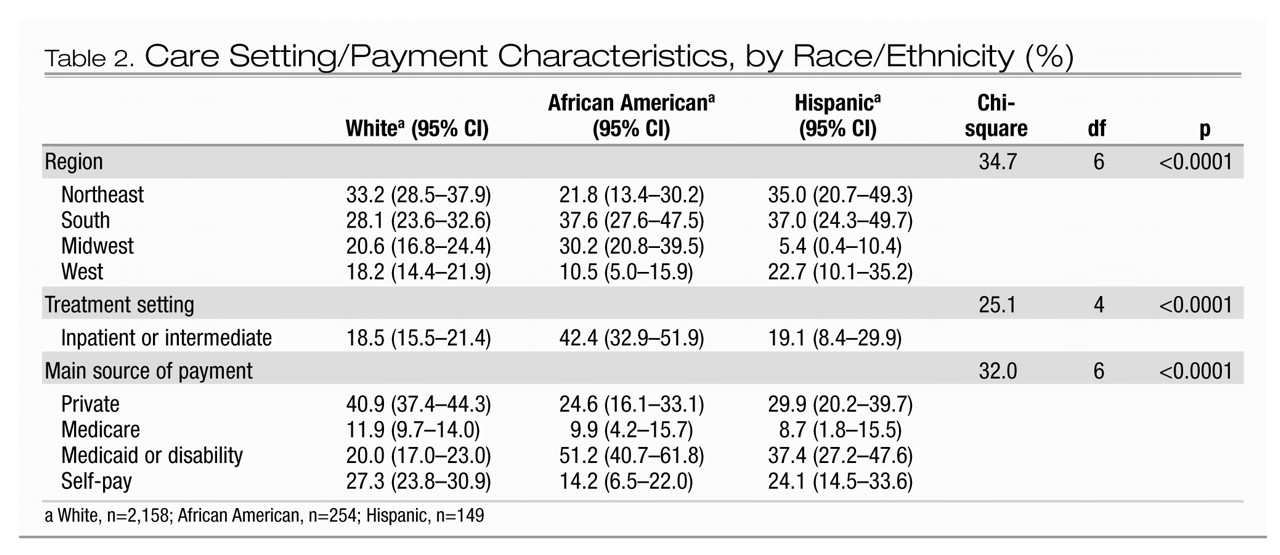

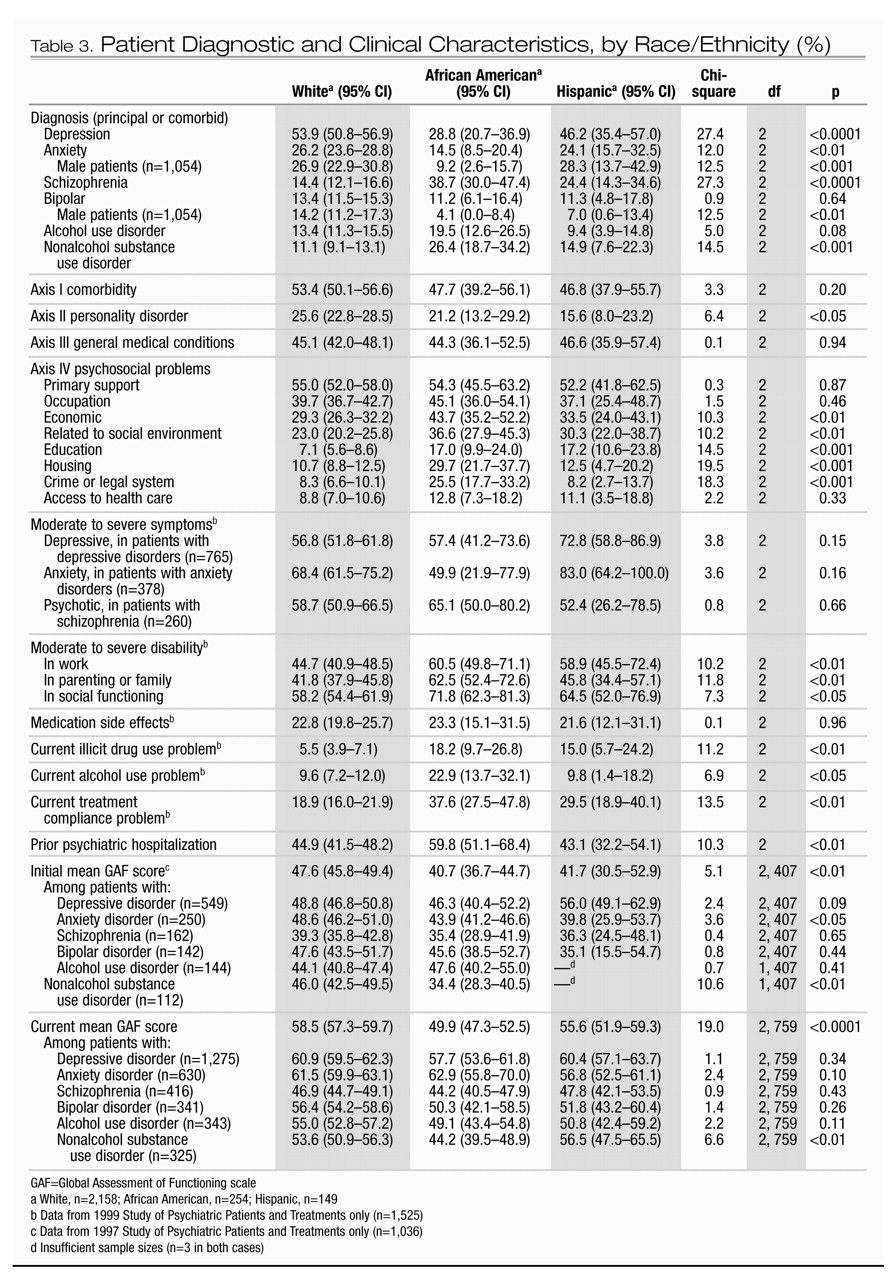

9). Tables 1–3 summarize the patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, care setting/payment variables, and the patients’ diagnostic and clinical characteristics.

Analytic plan

Weighted bivariate statistical tests for group differences were used to assess racial/ethnic differences in sociodemographic, diagnostic, clinical, and care setting/payment variables (Taylor’s chi-square for categorical variables and Wald’s F test for continuous variables). Logistic regression analyses in two stages were used to explore racial and ethnic differences: first the model was adjusted for sociodemographic variables and then for both sociodemographic and care setting/payment factors. The multivariate analyses were completed in two stages to measure the effect of each set of factors on the odds of receiving a specific diagnosis. Interactions of race/ethnicity and gender and of race/ethnicity and treatment setting were also tested to assess whether racial/ethnic differences in patterns of diagnoses varied across gender and setting.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

The majority of white and Hispanic patients were female, whereas the majority of African American patients were male (Table 1). African American patients were less likely than white or Hispanic patients to be married. Greater proportions of African American and Hispanic patients than of white patients were in the 18–34-year age group, completed less than 12 years of education, and were unemployed due to a mental or medical disability.

Care setting/payment characteristics

A substantially larger proportion of African Americans were inpatients (42.4%), compared with whites (18.5%) and Hispanics (19.1%) (Table 2). White patients were more likely to use private insurance (40.9%) than African American (24.6%) and Hispanic (29.9%) patients. A majority of African Americans (51.2%) used Medicaid to pay for their visit and/or were receiving Social Security or disability payments, compared with about one-third of Hispanics (37.4%) and one-fifth (20%) of whites.

Diagnostic characteristics

African American patients had significantly lower rates of depressive disorders (28.8%) than white patients (53.9%) (Table 3). Anxiety disorders were diagnosed less frequently in African American patients (14.5%) than in white patients (26.2%). The rates of depressive and anxiety disorders among Hispanic patients (46.2% and 24.1%, respectively) were similar to those among white patients. Among African American men, rates of anxiety and bipolar disorders were particularly low compared with white and Hispanic men. Bipolar disorder was reported for only 4.1% of African American men and 7.0% of Hispanic men, compared with 14.2% of white men. African American and Hispanic patients both had higher rates of schizophrenia spectrum disorders than white patients. About one in five African American patients had an alcohol use disorder, compared with about one in seven white patients and one in 10 Hispanic patients, although the differences were not statistically significant. Notably higher rates of nonalcohol substance use disorder were reported among African American patients than among Hispanic and white patients. Hispanic patients had significantly lower rates of personality disorders than white or African American patients.

Clinical characteristics

Approximately half the patients were reported to have more than one axis I condition (52.4%), and 45.1% were reported to have a general medical comorbidity; no statistically significant racial/ethnic differences were found in the number of axis I or axis III comorbid conditions (Table 3). African American patients experienced significantly higher rates of psychosocial problems related to their social environment, finances, and housing than white patients and somewhat higher rates than Hispanic patients. African American and Hispanic patients had significantly higher rates of problems related to education than white patients. African American patients also had a significantly higher rate of problems related to crime and the legal system than either white or Hispanic patients.

African American and Hispanic patients were reported to have higher rates of moderate to severe disability in occupational functioning than white patients. African American patients had a significantly higher rate of moderate to severe disability in family and social functioning than white patients. African American and Hispanic patients had higher rates of current illicit drug use problems than white patients, and African American patients had a higher rate of current alcohol use problems than white or Hispanic patients. African American and Hispanic patients both had markedly higher rates of treatment compliance problems than white patients. African American patients had a significantly higher rate of previous psychiatric hospitalization than white and Hispanic patients.

The mean score on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF) at the current visit was 49.9 for African Americans, 58.5 for white patients, and 55.6 for Hispanic patients. For subgroups with specific disorders, no significant differences in current GAF scores were found between racial/ethnic categories except in the case of nonalcohol substance use disorder; African Americans with a nonalcohol substance use disorder had a significantly lower current mean GAF score than whites or Hispanics. For patients with a nonalcohol substance use disorder, the initial mean GAF score was significantly lower among African Americans than among whites (Hispanics were excluded because the sample size was too small), and initial mean GAF scores for patients with anxiety disorders were lower among African Americans and Hispanics than among whites.

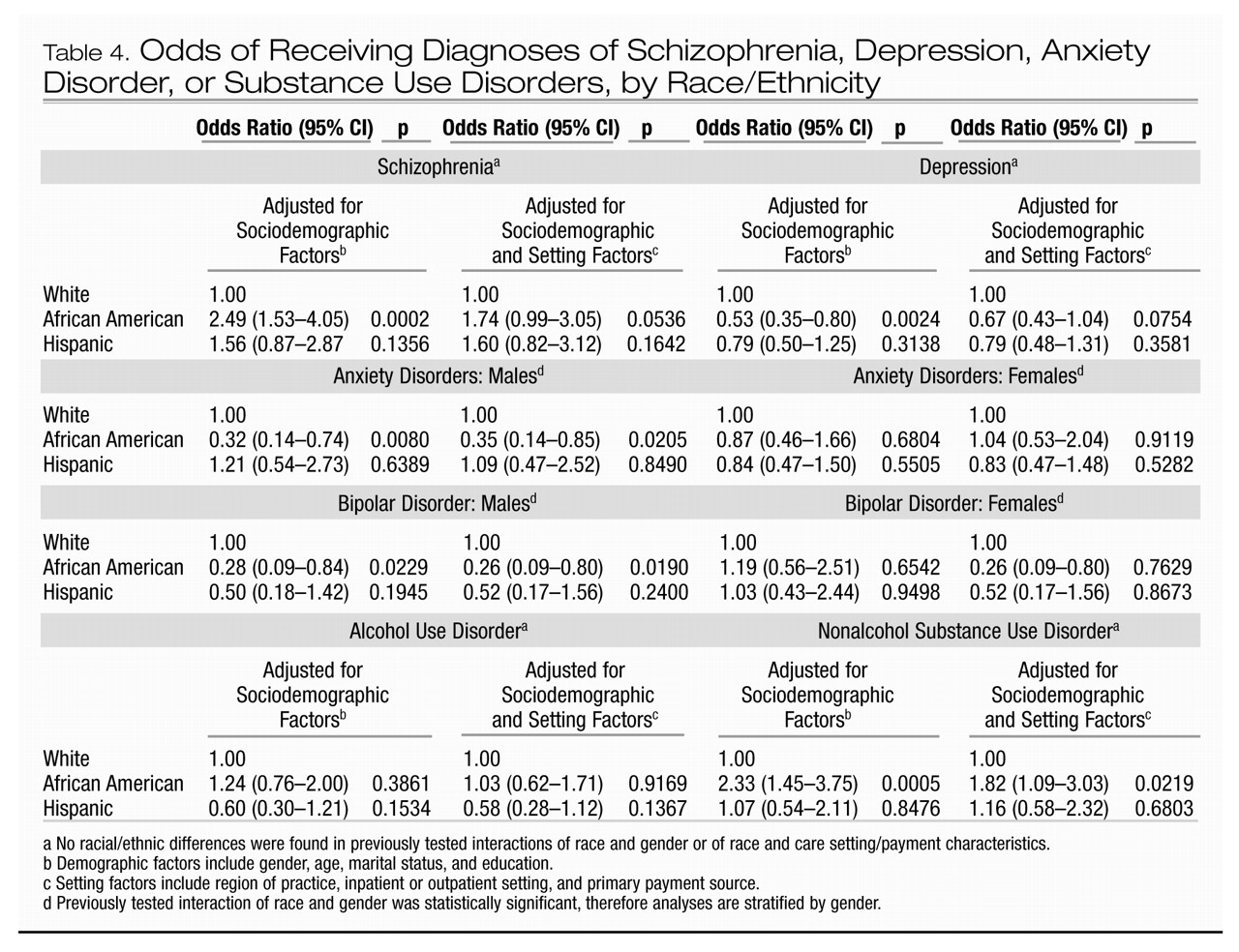

Diagnostic differences after adjusting for sociodemographic factors

After statistical adjustment for patients’ gender, age, marital status, and education, differences in diagnoses were observed for African American patients compared with white patients, but not for Hispanic patients (Table 4). African American patients were 2.5 times as likely as white patients to be diagnosed as having a schizophrenia spectrum disorder and 1.3 times as likely to be diagnosed as having a nonalcohol substance use disorder. African Americans were about half as likely as whites to be diagnosed as having a depressive disorder. No racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of having depression or schizophrenia were found in interactions of race and gender and of race and setting.

Because the interaction of race and gender was statistically significant in the multivariate analyses of bipolar and anxiety disorders, additional analyses, stratified by gender, were conducted. Racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of receiving a diagnosis of an anxiety or bipolar disorder were found for African American men compared with white men, but not for African American women. African American men were less likely than white men to be diagnosed as having bipolar disorder or anxiety disorder. African American patients were 2.3 times more likely than white patients to be diagnosed as having a nonalcohol substance use disorder. No racial/ethnic differences were observed in the likelihood of being diagnosed as having an alcohol use disorder.

Diagnostic differences after adjusting for sociodemographic and care setting/payment factors

After sociodemographic and care setting/payment factors were adjusted for, some diagnostic differences remained for African American patients; no differences were observed for Hispanic patients. African Americans remained more likely to be diagnosed as having a nonalcohol substance use disorder. After care setting/payment factors were adjusted for, the magnitude of the association between race and receiving a diagnosis of an anxiety or bipolar disorder remained constant and statistically significant for African American men compared with white men. Differences in the likelihood of having a substance use disorder remained statistically significant for African American patients compared with white patients.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

The primary strength of this study is that it used a large national sample of psychiatric patients to systematically examine racial/ethnic variations in patients’ diagnoses and clinical characteristics as ascertained by psychiatrists in routine psychiatric practice. The study is limited by its relying exclusively on psychiatrists’ reports, with no independent diagnostic validation or patient-reported data. Additional research with larger samples is needed, particularly to follow up on findings that show gender and race interactions among patients with bipolar and anxiety disorders. This study only examined patients treated by psychiatrists; the sample did not include patients treated by nonpsychiatrist clinicians or persons unable to access treatment. However, patients of psychiatrists are of particular interest given the role of psychiatrists in treating persons with severe mental illness and in providing psychopharmacologic treatments, which have become increasingly important in the treatment of psychiatric disorders.

Race/ethnicity and access to psychiatrists

While African American and Hispanic adults (that is, age 18 years and over) account for 11.5% and 11.0%, respectively, of the U.S. population, they appear to be underrepresented among psychiatric patients, as they only account, for 9.1% and 6.0% of the sample in this study (

9). In contrast, non-Hispanic whites make up 72.8% of the adult U.S. population, but 80.9% of this patient sample. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that minority patients are less likely to receive specialty mental health care (

1).

Race/ethnicity and clinical characteristics of psychiatric patients

In this study, African American patients were reported to be more severely impaired than white patients, as indicated by higher rates of moderate to severe disability in occupational, family, and social functioning; prior psychiatric hospitalization; axis IV psychosocial problems; and current problems with illicit substance and alcohol use. Hispanic patients were similar to white patients on these clinical variables, except that they had higher rates of moderate to severe disability related to work and problems related to education and current illicit drug use. African American patients were much more likely than white or Hispanic patients to be receiving care in inpatient and partial care settings. This finding suggests African Americans are more likely to access treatment from a psychiatrist after their illness has reached a level of severity where hospital-based care is needed. It may also reflect inadequate access to outpatient services or postdischarge mental health services to prevent readmission among African Americans.

Both African American and Hispanic patients had higher rates of treatment compliance problems, which suggests that they may be less satisfied with or less able to comply with or continue treatment. However, the extent to which patient preferences, economic, or care setting/payment factors contribute to their higher rates of treatment compliance problems warrants further examination. Analyses of patient functioning by specific diagnoses indicated that among patients with mood disorders, schizophrenia, or alcohol use disorder, minority patients have GAF scores similar to those of white patients. Thus, the higher overall levels of impairment and clinical problems observed in African American patients are likely due to the higher rates of more severe forms of mental illness in this population relative to white psychiatric patients.

Race/ethnicity and variations in patient diagnostic characteristics

Given findings reported in previous research (

3), we would have expected the racial/ethnic differences in diagnoses to diminish after the analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic and care setting/payment factors. Although the observed racial/ethnic differences in diagnoses remained after adjustment for sociodemographic factors, some of the initially observed differences were no longer statistically significant after adjustment for care setting and payment factors. Although there may be some residual confounding in these measures, this study identified significant racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of receiving a diagnosis of bipolar, anxiety, and substance use disorders.

Racial differences in the likelihood of receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia or depression appeared to be strongly associated with care setting/payment factors. When patients’ source of payment, treatment setting, and region were controlled for, the increased odds of African Americans’ receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia or depression were no longer statistically significant.

Although African Americans were much more likely to be inpatients and inpatients were three times as likely as outpatients to have a substance use disorder, after adjustment for care setting/payment factors, African American patients remained about twice as likely as white patients to be diagnosed as having a substance use disorder. Among patients treated by psychiatrists, substance use disorders frequently co-occur with schizophrenia and are less often seen or detected among patients with depression (

11). The greater likelihood of substance use disorders among African American patients may reflect a real difference in the rates of these disorders and the overall racial/ethnic differences in depression and schizophrenia among African American patients compared with white patients. The pathways to receiving treatment from a psychiatrist for African Americans may also be such that African Americans are more likely to seek or obtain treatment from a psychiatrist for substance use disorders than for other disorders, such as mood and anxiety disorders. Alternatively, it may be that substance use disorders are more likely to be detected and treated among African American patients than among white patients.

Conclusions

Our data showed that minority patients presented with more disabling conditions, greater impairment in functioning, and greater levels of psychosocial problems. As indicated in previous studies (

5,

12), delays in treatment, more limited access to treatment, and greater barriers to treatment may contribute to a greater severity of illness at presentation for minorities, posing greater challenges to accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. As previous studies indicate, another possible explanation for the racial/ethnic differences in diagnoses is that clinicians may not accurately perceive and evaluate the emotional distress of African Americans, and as a result, African Americans may be underdiagnosed for bipolar disorder, depression, and anxiety disorders. Some hypotheses that have been proposed to explain diagnostic inaccuracy with African American patients focus on patterns of psychiatric presentation and clinicians’ use of cues in diagnostic decision making; for example, presenting symptoms among depressed African Americans may differ from those among depressed white Americans (

13–

15). Other explanations have pointed to historical myths about African Americans’ being unlikely to have certain types of psychiatric illnesses (e.g., the myth that African Americans do not get depression) (

16). Finally, another factor in the misdiagnosis of African Americans has focused on the patient care dynamics of the public mental health care system, which is where most African Americans receive their mental health care (

8), and the limited time and resources available in this setting for a thorough, careful diagnostic examination. Data (not shown) from this sample of patients indicated that the initial visit lengths for patients with public insurance were shorter than those for patients with private insurance.

An important next step in this avenue of research is psychometric validation of patients’ diagnoses and current symptoms, which would help in clarifying the extent to which these observed differences in diagnoses may reflect differential patterns of detection or assessment or actual differences in the rates of these disorders in psychiatrists’ caseloads. PRN studies that collect information from patients and independently assess symptoms are now being conducted. Additional research is also needed to better understand and quantify the extent to which these observed differences in diagnosis are due to racial, ethnic, or cultural differences in patients’ treatment-seeking behaviors or preferences, racial or ethnic differences in access to care, or differences in patient referral practices and pathways to treatment. Among the issues that need further study is the relative influence of stigma and cultural attitudes toward mental illnesses and disabilities across different racial and ethnic groups. Clarifying the influence of gender will also be an important research task, given our findings indicating that gender may play a key role in the racial/ethnic differences in the diagnosis of bipolar and anxiety disorders. Another area to explore is whether—and if so, to what extent—there are different tolerance levels or thresholds for obtaining treatment among minority and nonminority groups, given our findings showing that African American and Hispanic patients present with significantly higher levels of impairment compared with white patients. We also need to develop our understanding of the role of enabling and predisposing factors to obtaining treatment across racial/ethnic groups as well as the role of the financing, organization, and delivery of care and of organized delivery systems in facilitating or impeding pathways to treatment.