With the first report of lithium’s efficacy in 1949 by Cade, bipolar disorder has the longest record of treatment efficacy among the major Axis I disorders. Furthermore, after more than half a century of clinical research, multiple agents from many different pharmacological classes have shown at least some efficacy, while many other agents (albeit without a consistent database demonstrating their utility) are prescribed regularly by clinicians. Yet, despite this plethora of choices, treatment of bipolar disorder remains suboptimal from the points of view of clinicians and patients alike. Whether measured by recovery time from manic or depressive episodes or preventive efficacy of maintenance treatments, bipolar disorder is characterized by sluggish responses, inadequate responses, poor compliance and recurrences in controlled clinical trials. Results of naturalistic studies additionally show pervasive, often chronic symptoms, multiple episode recurrences, very infrequent euthymic periods when measured over years and marked functional disability in many patients. Thus, despite the explosion of options over the last quarter century when lithium dominated treatment, treatment resistance remains a central problem in bipolar disorder.

Natural history of treated bipolar disorder

Without a consensual definition of treatment resistance, it is impossible to estimate the number of treatment-resistant bipolar patients. However, observing the course of naturalistically treated patients may give some indication of how effective typical treatments are. A number of studies over the last decade have demonstrated both high recurrence rates and symptom chronicity of bipolar patients treated naturalistically. In the largest recent naturalistic study in the United States, Judd

et al. followed both bipolar I patients (

n = 146) (

1) and bipolar II patients (

n = 86) (

2) for a mean of approximately 13 years, using prospective mood ratings. Bipolar I patients were symptomatically ill for 47% of the weeks, while bipolar II patients were symptomatic for 54% of the observed weeks. Sub-syndromal symptoms were more common than syndromal states in both bipolar Is and IIs. Depressive symptoms were more common than manic/ hypomanic symptoms by a 3:1 ratio in bipolar I patients. In bipolar II patients, depressive weeks outnumbered hypomanic weeks by a 39:1 ratio. Polarity shifts occurred an average of 3.5 times per year in Bipolar Is and 1.3 times per year in Bipolar IIs. Thus, for these patients, symptoms were chronic, subsyndromal and primarily depressive. Since these patients were treated in an open, naturalistic manner, it is impossible to make judgments as to whether a systematic treatment algorithm might have improved the outcome of these bipolar patients. Nonetheless, it is clear that, for many patients, although treatment might be more effective than no treatment, mood symptoms and polarity shifts still dominate the clinical picture, implying that our typical treatments are woefully inadequate for sustaining euthymic mood over a long period of time.

Additionally, other studies of bipolar patients consistently demonstrate that naturalistically treated patients do poorly, as measured by social relationships, occupational status, quality of life and other measures of function (

3). Of course, a clear relationship exists between symptom/syndromal outcome and functional outcome (

4). This relationship, however, is far from linear and may best be described as circular, with poor outcome in either domain predicting poor outcome in the other domain (

5). Thus, whether measured by symptom/ syndrome/recurrence status or functional status, the majority of treated bipolar patients have a less than satisfactory outcome.

Definitions of treatment-resistant bipolar disorder

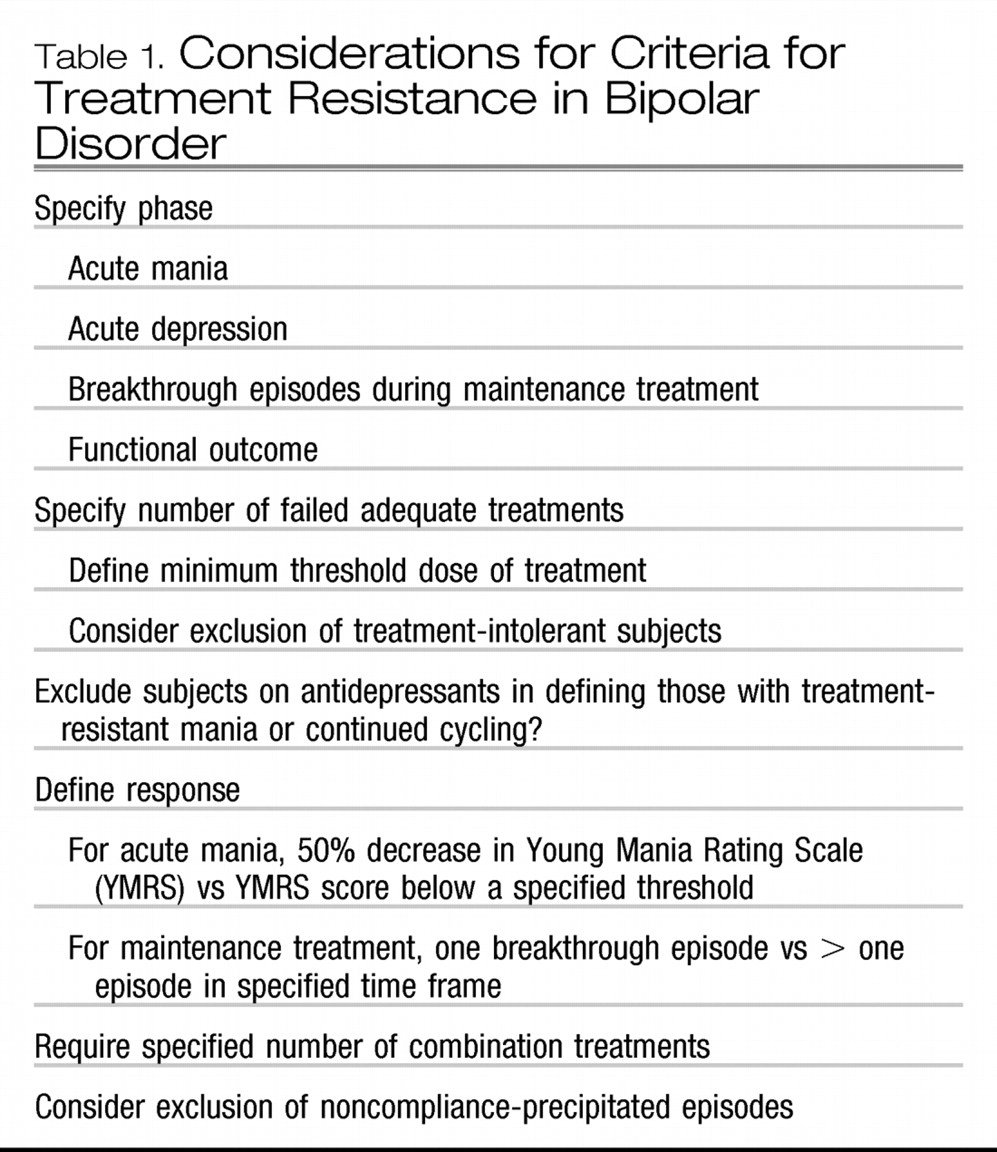

No consensual definitions of treatment-resistant bipolar disorder exist. A number of parameters should be considered in the definition, as delineated in Table 1.

First, the phase of the disorder should be specified. In most studies, these are either acute manias or breakthough episodes during maintenance treatment. Definitions of treatment-resistant bipolar depression have generally not been considered. For bipolar depression, criteria used for treatment-resistant unipolar depression would apply, (

6) with the proviso that failure to respond to mood stabilizers as well as antidepressants should be added to the definition. Since most definitions of treatment resistance are symptom and syndrome based, functional outcome is rarely considered in the definition of treatment resistance. However, from the patient and family’s viewpoint and from a public health perspective, it should be considered.

Most definitions for treatment resistance in acute episodes (either mania or depression) utilize the failure to respond to a specified number of treatments that are generally considered effective (

6). Similarly, treatment resistance in maintenance treatment is typically defined as continued cycling despite adequate trials of previously demonstrated effective treatments. In most studies, failure to respond to a specified number of prior treatments (typically two or three) is used as the threshold for treatment resistance. Some studies, however, include subjects who either fail to respond or are intolerant of prior treatments (

7,

8). Conflating treatment resistance with treatment intolerance unfortunately dilutes the sample treated, since these two groups are arguably distinct. A similar distinction has been made in the treatment-resistant depression literature in which treatment-non-responsive patients who have been unable to tolerate adequate antidepressant trials are specified as pseudoresistant to distinguish them from true treatment failures. Some authors (

9) additionally require the absence of antidepressants in the definition of both acute mania and maintenance treatment, reasoning that the antidepressant could either exacerbate the mania or ‘drive’ the mood instability. Finally, given the frequency with which bipolar patients are treated with medication combinations, future definitions of treatment resistance in bipolar disorder should consider requiring a failure to respond to one or more combination treatments, whether in acute mania or in maintenance treatment.

Since treatment non-compliance in bipolar disorder is so common, especially in maintenance treatment (

10), both researchers and clinicians alike need to be alert to patients whose seeming treatment resistance is based not on a failure to respond but simply because treatment was discontinued, either fully or partially. Treatment strategies would surely differ between non-compliance-precipitated episodes and cycling vs true breakthrough episodes. Of course, if a manic episode occurs in the context of non-compliance, it is imperative to establish whether the patient discontinued treatment and the episode followed, or whether the patient became hypomanic, discontinued treatment at that point and then became even more symptomatic.

First-line treatments for bipolar disorder

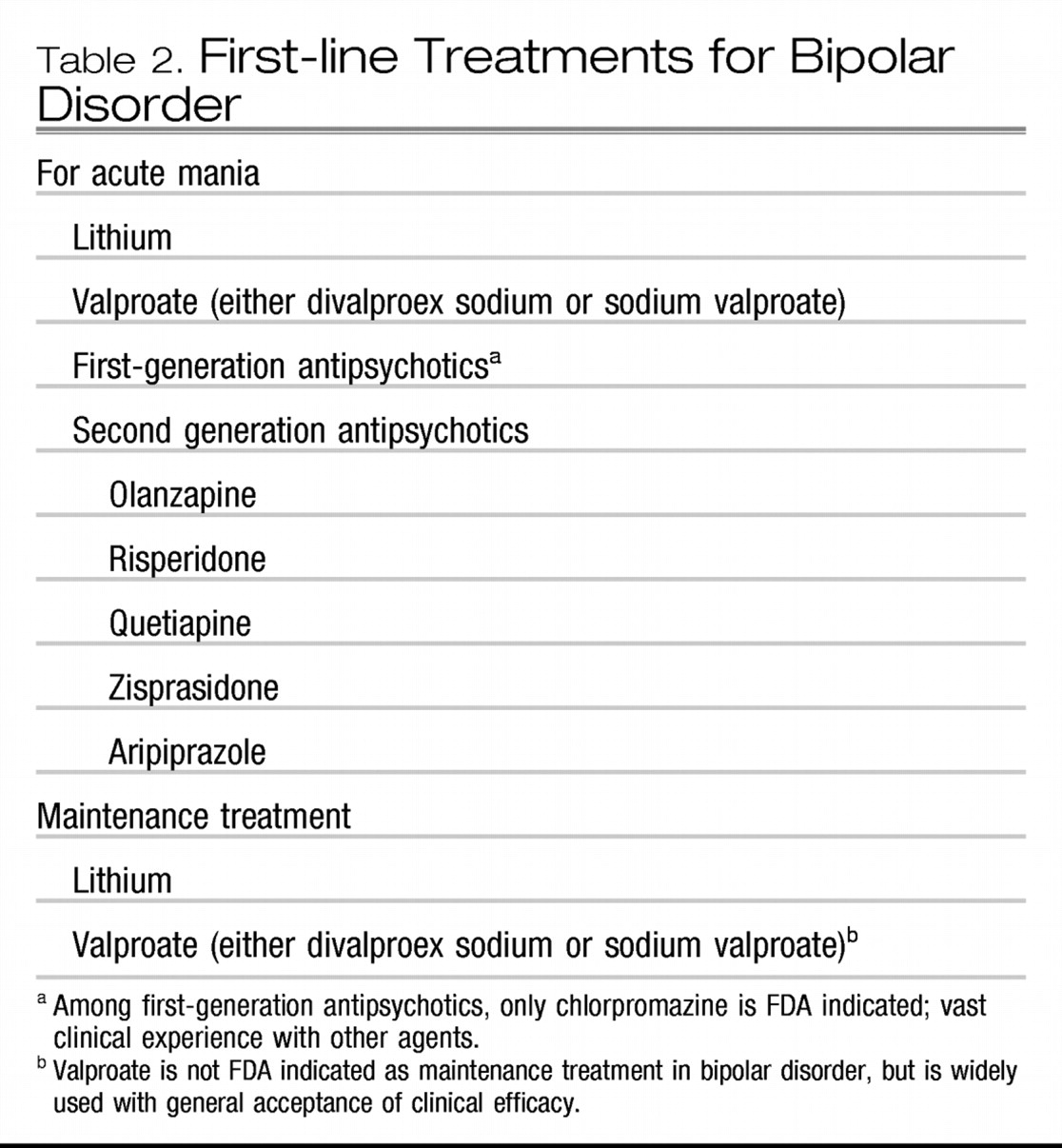

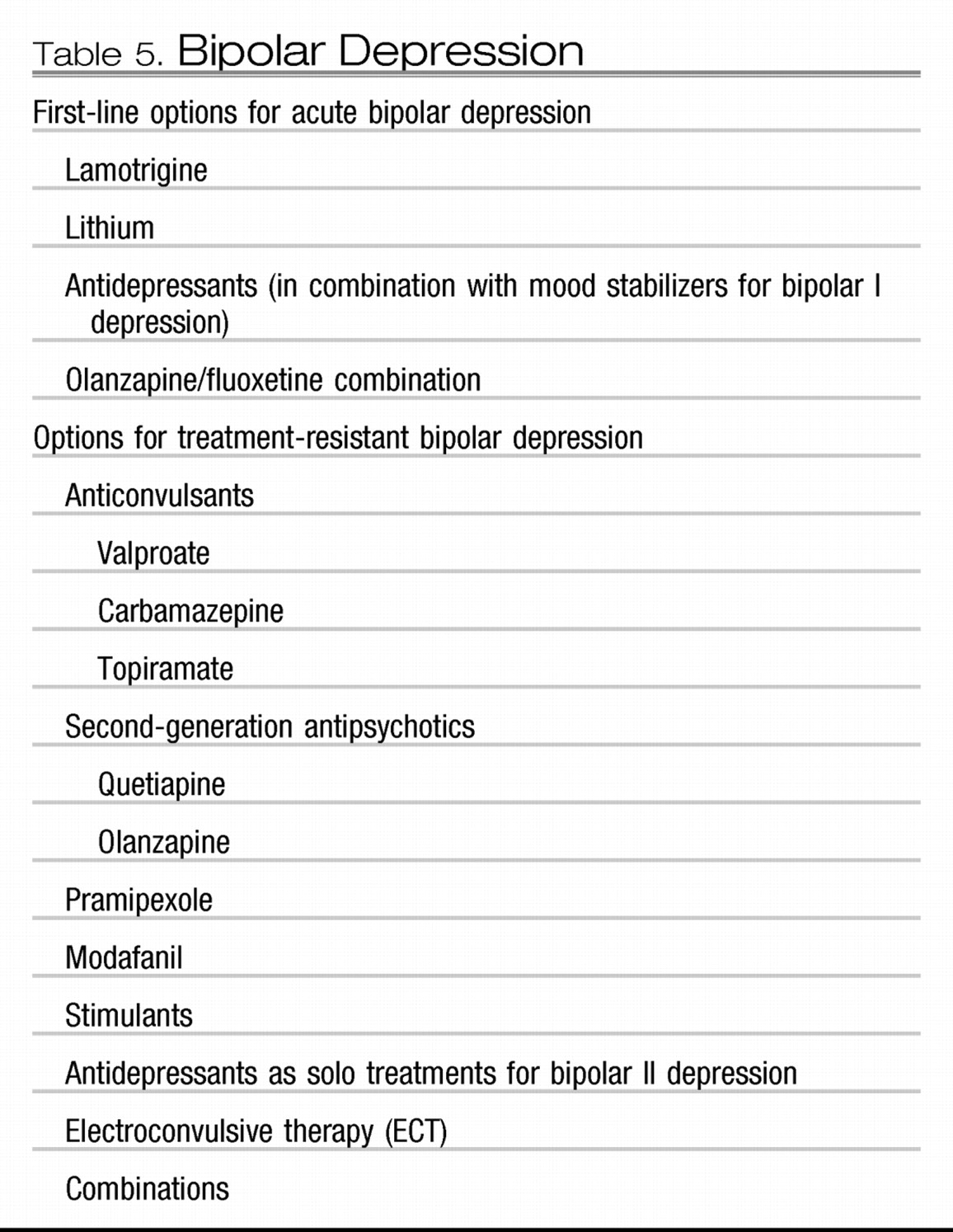

Established first-line treatments, used for at least a decade and/or for which there are ample clinical and research data, are listed in Table 2.

For acute mania, first-line treatments have long included lithium, valproate and first-generation anti-psychotics (FGAs). However, among the FGAs, only chlorpromazine has received a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indication for this purpose. Five of the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are FDA indicated for acute mania. Even though their use in treating acute mania is relatively recent, they are listed as first-line agents since they are generally used first line in most inpatient settings. No published data currently exist supporting the use of one of the SGAs vs another in treating acute mania. Nonetheless, at least in inpatient settings, aripiprazole and ziprasidone are prescribed less frequently than risperidone, olanzapine or quetiapine. This assuredly reflects both the earlier release in the United States of the three latter agents as well as the greater sedation associated with their use. Sedation is often used on inpatient units for behavioral control as well as for treating the acute mania itself.

For maintenance treatment, lithium has long been a mainstay, receiving an FDA indication for this purpose in 1974. Valproate (either divalproex sodium or generic valproic acid) is not FDA indicated for maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder, due to its lack of separation from placebo in a large, placebo-controlled study (

11). A number of methodological factors may explain this unanticipated result, including the requirement of more consistent euthymia in subjects and the use of a non-enriched sample (in contrast to later studies evaluating olanzapine (

12) and lamotrigine (

13) in which study design utilized an enriched sample). Nonetheless, clinical consensus, Expert Consensus Guidelines, (

14) published algorithms (

15) and Practice Guidelines (

16) all support the efficacy of valproate as a first-line maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder.

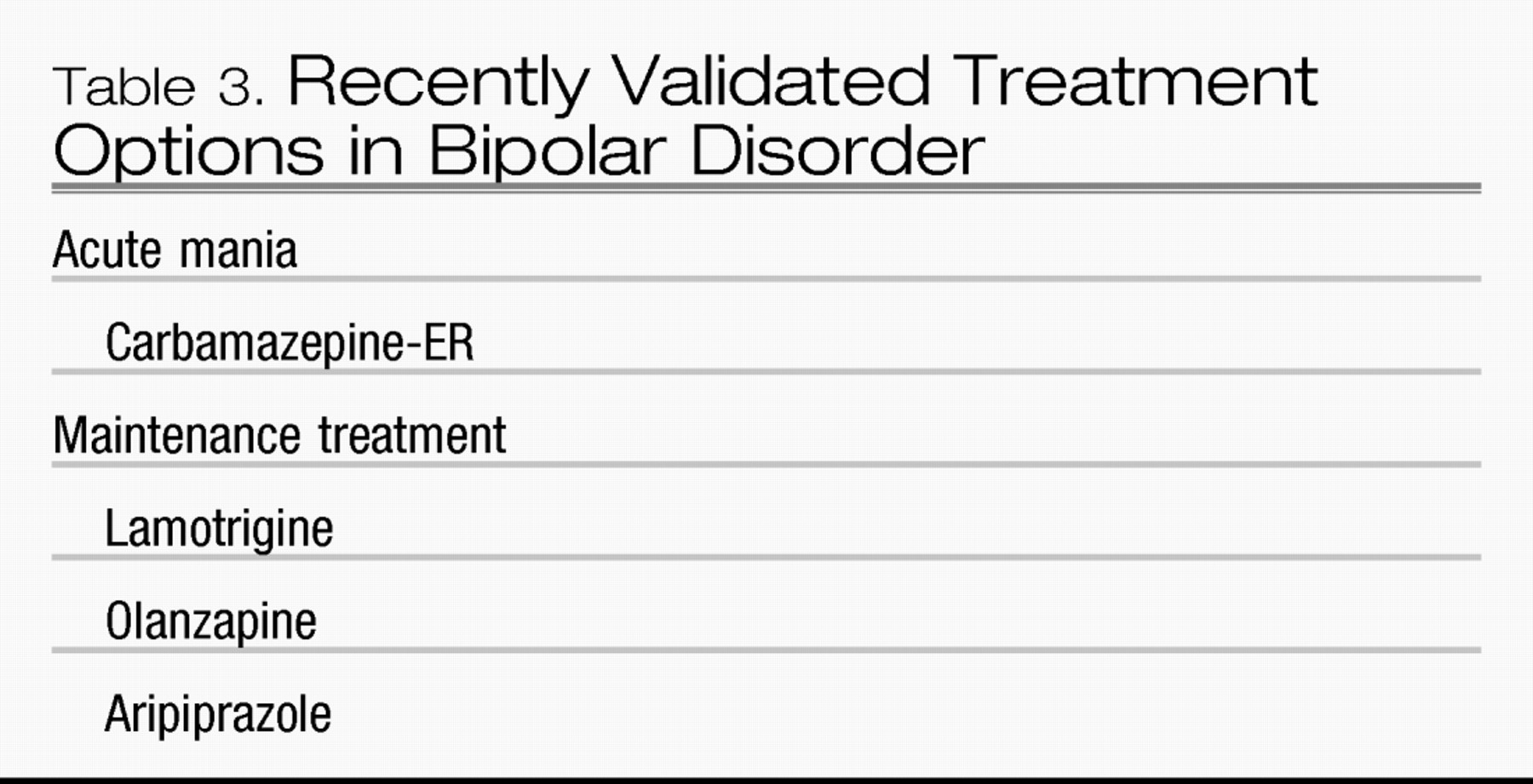

Recently validated treatment options in bipolar disorder

Although carbamazepine was the first anticonvulsant used in treating acute mania, few well-controlled studies supported its use as a first-line agent in treating acute mania (Table 3). Additionally, the loss of the original patent protection well over a decade ago stopped any pharmaceutical firm support for research into carbamazepine’s efficacy. More recently, however, an extended release preparation of carbamazepine has shown efficacy as an acute antimanic treatment in two double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (

17,

18). On the strength of these data, carbamazepine-ER received an FDA indication for acute mania.

Until 2003, lithium was the only mood stabilizer with an FDA indication as a maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Over the last 2 years, however, three additional treatments have received FDA indications as maintenance treatments.

In two studies, evaluating recently manic/hypomanic and recently depressed patients, lamotrigine successfully prevented mood episode recurrences as measured by the time to intervention (

19,

20). Since the design for these two studies is identical, with the exception of the pole of the most recent episode (recently manic/hypomanic (

19) vs depressed (

20)), the results of these two studies were combined and the data reanalyzed (

13). In this analysis, lamotrigine effectively prolonged the time to intervention for both manias and depressions independently compared to placebo (

P = 0.034 and 0.009, respectively). Of note, lithium was used as an active comparator in these studies. In the combined analysis, lithium was significantly more effective than lamotrigine in prolonging time to mania,

P = 0.03 (even though both active treatments were more effective than placebo), while lithium was not more effective than placebo in prolonging time to depression,

P = 0.12.

Two SGAs have additionally demonstrated efficacy as maintenance treatments in bipolar disorder with both receiving FDA indications. Olanzapine has been evaluated in three different controlled trials with comparisons to placebo, (

12) lithium (

21) and divalproex (

22). In the placebo-controlled trial, olanzapine significantly decreased total relapses (relapse rates = 80 vs 47%,

P < 0.001), manic relapses (41 vs 16%,

P < 0.001) and depressive relapses (48 vs 34%,

P < 0.02). (

12) In a 1-year trial with no placebo controls, olanzapine (mean daily dose = 13.5 mg) was somewhat more effective than lithium (mean serum level = 0.7 mEq/l) in preventing symptomatic recurrence of mood episodes (

P = 0.055) (

21). No significant difference in depressive recurrence rates were seen, while significantly fewer olanzapine-treated patients had manic/mixed recurrences compared to lithium-treated patients (23 vs 14%,

P < 0.02). In the 47-week non-placebo-controlled trial comparing olanzapine vs divalproex sodium, no significant differences between the two medications were seen in overall recurrence rates (

P = 0.42) (

22). However, treatment discontinuation rate during this study across both treatment groups was 84%, with the majority of patients discontinuing for reasons other than lack of efficacy.

In a 6-month study, aripiprazole was more effective than placebo in preventing mood episodes (43 vs 25%,

P = 0.013) in 161 patients (

23).

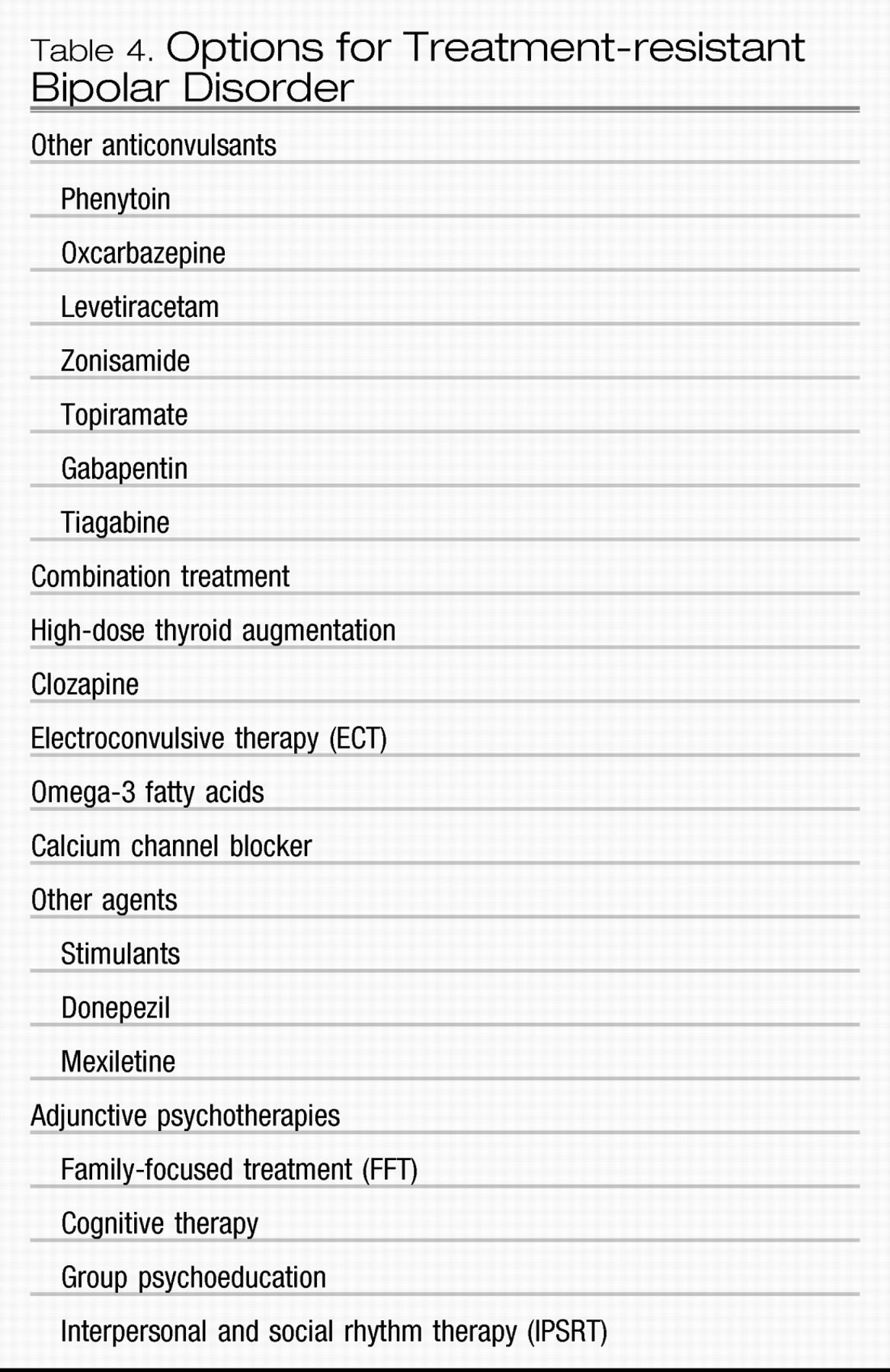

Anticonvulsants

Aside from the anticonvulsants listed above, all recently released anticonvulsants and one older agent have been evaluated, either in open-case series or in some controlled trials, in bipolar disorder. In the following review, only case series with five or more subjects will be discussed.

Ironically, phenytoin, the oldest of the agents, is the only anticonvulsant in Table 4 with any substantially controlled data supporting its use in bipolar disorder. In a double-blind placebo-controlled, add-on study of a small (

n = 30) sample of acutely manic patients, phenytoin 300 – 400 mg daily demonstrated additive efficacy to haloperidol (

25). In a second small (

n = 23) study by the same group, phenytoin was compared to placebo when added blindly to ongoing maintenance treatment using a crossover design of 6 months each (

26). Phenytoin-teated patients had fewer recurrences (

P = 0.02).

Oxcarbazepine, a congener of carbamazepine, has been prescribed over the last few years for treating both acute mania and as a maintenance treatment. Only one double-blind, placebo-controlled study for acute mania has been published, but only seven subjects were included in the study (

27). Three other controlled studies (two of which had sample sizes of 12 and 20, respectively) in acute mania have been published, comparing oxcarbazepine to lithium, valproate or haloperidol, but none were placebo controlled (

27). In these studies, oxcarbazepine seemed equivalently effective to the active comparators. Despite the lack of controlled data, clinicians prescribe oxcarbazepine given its biological similarity to carbamazepine and its record of better tolerability (

28). Owing to patent issues, large-scale studies on oxcarbazepine’s efficacy in bipolar disorder are unlikely to be forthcoming.

Four open studies, with an aggregate of 79 subjects, have examined the potential efficacy of levetiracetam in bipolar disorder (

29 –

32). In the largest of these reports, 34 patients who were either manic/hypomanic or depressed received 500–3000 mg daily of levetiracetam adjunctively (

32). The more mildly depressed patients seemed to respond although the open design of the study precludes any clear interpretation of the results seen. In earlier open trials, mania/hypomania seemed to improve when levetiracetam was prescribed either as a solo treatment or in an add-on design in daily doses up to 4000 mg.

Three open studies have evaluated the efficacy of zonisamide in mania or bipolar depression (

33–

35). In the largest and most recent of these reports, zonisamide 100–500 mg daily was added to the ongoing regimen of 62 bipolar outpatients, most of whom were treatment-resistant with either predominantly manic/hypomanic or depressive symptoms (

35). Those with manic/mixed symptoms seemed to respond, while those with depressive symptoms showed a more modest response. Of note, only 18% of patients completed the 1-year trial, mostly due to worsening mood state or lack of improvement. Modest weight loss was observed over the course of the trial.

When first evaluated in the treatment of bipolar disorder, topiramate showed promise, both for the initial positive reports in open trials (

36) and for its documented weight-losing properties (

37,

38). Unfortunately, in a series of controlled trials for acute mania, topiramate was no better than placebo (

39). A mono-therapy trial comparing topiramate vs placebo in acute manic episodes in children and adolescents was terminated prematurely due to the negative adult data (

40). However, analysis of the smaller than designed sample showed some efficacy of topiramate compared to placebo. Finally, a relatively large open-label study of adjunctive topiramate as a maintenance therapy showed efficacy in both manic and depressive phases and in overall symptom reduction (

41). Thus, topiramate’s efficacy as a maintenance treatment, either adjunctively or as a solo agent, is still unknown.

Despite a number of positive open trials and widespread clinical use, gabapentin has not shown antimanic or general mood-stabilizing properties in two controlled trials (

42,

43). In the first trial, gabapentin was an ineffective add-on treatment compared to placebo in manic/hypomanic outpatients (

42). Gabapentin was also ineffective in (mostly) rapid cyclers whether rated for antimanic, antidepressant or overall mood-stabilizing properties (

43). It may, however, be helpful in treating anxiety in bipolar patients (

44).

Three trials, all open label, with a total of 47 treatment-resistant subjects have evaluated the efficacy of tiagabine in both manic, depressive or maintenance phases of treatment (

45–

47). None of the three trials showed particular efficacy in doses between 1 and 40 mg. Four subjects across the three studies (8.5%) without a prior history of epilepsy had either well-documented or presumptive seizures. With both poor efficacy and tolerability concerns, tiagabine should not be considered a primary option even for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder.

Combination treatments

Despite the focus on placebo-controlled monotherapy studies, whether for acute mania or as a maintenance treatment, monotherapy in clinical practice is the exception rather than the rule (

48). As an example, using data collected a decade ago on bipolar outpatients, fewer than one in five were on monotherapy and the majority of patients were being treated by three or more medications, with one-third receiving four or more medications (

48). Similarly, in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network database reported in 2004, bipolar patients received a mean of four different psychotropic medications during 1 year (

49). Finally, a pharmacy database recently found that 55% of bipolar outpatients were taking two or more medications (Market Measures, 2003, unpublished data).

In treating acute mania, a substantial database consistently demonstrates the superiority of combination treatment over monotherapy. The most common design is the comparison of an SGA plus an older mood stabilizer, typically lithium or valproate, compared to lithium or valproate alone. Consistently, the combination, with controlled studies available for risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine, shows significantly greater efficacy (

50). In some of these add-on studies, only patients who have failed monotherapy are included, while other studies examine combination vs single treatment in all eligible patients. Response rates for combination treatments of acute mania generally exceed those of lithium or valproate by 20–25%. No published studies have evaluated the additive efficacy of lithium or valproate to an SGA. In the only study of its type, valproate showed additive efficacy in the treatment of acute mania when added to a FGA (

51).

Far fewer studies have compared the efficacy of a combination treatment to monotherapy in the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder. The few published controlled studies are marred by small sample sizes, large dropout rates or unrepresentative tertiary care patients. Over the last decade, only three controlled trials of combination maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder have been published (

52–

54). In the only large-scale controlled study, olanzapine plus lithium or valproate was compared to lithium or valproate alone over 18 months in 99 patients who had responded to the combination for acute mania (

52). Dropout rates were very high; 69% of those on combination and 90% of those on lithium or valproate alone discontinued the study, with the majority of dropouts occurring for reasons other than relapse. Modest additional significant efficacy was seen with the combination as measured by median time to symptomatic relapse (as measured by rating scale scores)

P = 0.023, but not by syndromal relapse rates (29 vs 31%) or time to syndromal relapse.

An initial maintenance treatment pilot study compared the relative efficacy of lithium plus divalproex sodium vs lithium alone in bipolar patients treated for up to 1 year (

53). Combination treatment was significantly more effective than lithium alone in preventing relapse (0/5 vs 5/7,

P =0.014). Combination treatment was associated with significantly greater side effect burden and a higher study dropout rate due to side effects. Despite these intriguing preliminary findings, a larger follow-up study has not been presented or published.

A larger crossover study compared lithium, carbamazepine and the combination in 52 bipolar I and II patients, with each subject receiving each medication and the combination for 1 year each (

54). Using Clinical Global Improvement (CGI) scores, the three treatments did not differ significantly, although a good treatment response was seen in 33% of patients on lithium, 31% on carbamazepine and 55% on the combination. Of note, the combination was significantly more effective in rapid cycling patients who did poorly on both solo agents. Additionally, a subset of patients showed differential improvement to one or the other monotherapy, implying that trials of multiple monotherapies may be worthwhile for those who do not respond to the first agent.

Clinically, and in case reports and case series, virtually all medications with mood-stabilizing properties have been used in combination. (This includes clinical situations in which patients are sometimes treated with four or more mood stabilizers.) The only combination that may be relatively contraindicated is that of carbamazepine and clozapine, since each produces potentially serious hematological effects (

55). With many medication combinations, especially those involving carbamazepine and/or valproate, pharmacokinetic interactions must always be considered.

High-dose thyroid augmentation

The use of high-dose thyroid augmentation for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder has been evaluated, mostly in open trials, for over 20 years. Despite this length of time, only a handful of reports, none large-scale and none using classic-controlled methodologies, have been published. (One of the older studies employed the only controls–single- or double-blind placebo substitution – in four of 10 treatment responders. (

56)) In aggregate, only 29 subjects, some of whom were unipolar depressives, all from the same research group, have been evaluated in the studies published over the last 15 years (

57–

59). (Some of the subjects in two earlier reports (

57,

58) are included in the later paper. (

59)) Nonetheless, high-dose thyroid hormone augmentation continues as a potential option for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder.

The paradigm of thyroid augmentation for bipolar disorder–which is distinct from the use of sub-replacement doses of triiodothyronine as an adjunct for treatment-resistant depression–typically involves administering high doses of

l-thyroxine for months to years with the goal of decreasing cycle frequency, mood episode amplitude or both. Mean doses of

l-thyroxine in the two recent publications were 379 (

59) and 482 mcg (

58), between 3 and 4.5 × the daily thyroid replacement dose in the United States. Thus, patients were treated with supraphysiological doses. In both open studies, treatment-resistant patients showed clear improvement with mean follow-ups of 2 and 4 years, respectively. Side effects were surprisingly minimal, given the high doses of thyoxine prescribed. Concerns regarding the potential for the development of osteoporosis in patients taking high doses of thyroid hormone over extended time periods continue despite preliminary reassuring results (

60,

61).

Clozapine

Alone among the SGAs, clozapine has not been the subject of large-scale double-blind studies in bipolar disorder. This assuredly reflects clozapine’s side effect profile, compliance burden and dangers of the drug such as cardiomyopathies, seizures and agranulocytosis with the mandated regular checks of white cell counts. Another factor explaining the lack of controlled studies is clozapine’s loss of patent protection years ago. Nonetheless, a large uncontrolled literature suggests that clozapine must be considered as a treatment for refractory bipolar disorder, similar to its use in schizophrenia (

62).

Despite the limitations of an uncontrolled database, clozapine has shown efficacy in treating acute mania, decreasing depressive symptoms and in overall mood stabilization. Psychotic symptoms do not predict an inherently better response to clozapine among treatment-resistant bipolar patients. Furthermore, among treatment-resistant patients, compared to schizophrenic patients, those with bipolar disorder may be more responsive to clozapine. (

63) Required doses for optimal effect in bipolar disorder may be less than for treatment-resistant schizophrenia (

64).

Only one study has systematically compared clozapine as an add-on study to a treatment as usual group using a random assignment but not blinded design (

65). In this study of 38 treatment-resistant bipolar I and schizoaffective patients, after 6 months of treatment, clozapine significantly decreased symptoms by 30% or more in 82% of patients compared to 57% in the treatment as usual group. Using multiple rating scales, clozapine addition was consistently significantly more effective other than in depression rating scale scores (with the difference in depression scores differing at a significance level of 0.06).

Electroconvulsive therapy

Although uncommonly used in bipolar disorder, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) remains an important option for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder in manic (

66) and depressive phases (

67) and as a maintenance treatment (

68).

For acute mania, only two relative small prospective, controlled studies have systematically compared ECT to other treatments – lithium (

69), and lithium plus haloperidol (

70). ECT was slightly more effective than lithium in one study and clearly more effective than the combination treatment in the other study. It is estimated that ECT is associated with remission or marked clinical improvement in 80% of those treated (

66). No consistent evidence exists suggesting the need for more ECT treatments in manic compared to depressed patients.

No controlled studies have examined maintenance ECT. Naturalistic studies, which have typically included both unipolar and bipolar patients, consistently suggest efficacy (

68). In the most recent case series, 13 treatment-resistant bipolar I, II and schizoaffective patients, 10 of whom were over 65 years old, showed overall improvement (as measured by decreased numbers of hospitalizations) with maintenance ECT. Maintenance ECT was generally given weekly, with no patient able to extend beyond 3-week treatment intervals. Additionally, two patients refused further maintenance ECT after four treatments: one discontinued treatment due to cognitive side effects, while another showed cardiac complications. Thus, although maintenance ECT may be effective, longer times between treatments (e.g., monthly intervals) is unlikely to be effective and, in older patients, medical complications may be significant.

Omega-3 fatty acids

Although an initial double-blind, placebo-controlled study indicated the potential efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids as an adjunctive treatment in bipolar disorder, no positive data have emerged over the last 5 years. In the initial study, 30 bipolar patients (40% rapid cyclers), not selected for operationally defined treatment resistance, were assigned to omega-3 fatty acids, 9.6 g/day added to their ongoing treatment regimen vs placebo for 4 months. (

71) Those treated with omega-3 fatty acids showed significantly longer period of remission (

P =0.002), primarily due to prevention of depressive symptoms. These results were consistent with a small open trial of 12 patients with bipolar I depression treated with the omega fatty acid eicosapentanoic acid (EPA) in which eight of 10 patients treated for at least 1 month showed an antidepressant response (

72).

Unfortunately, the largest recent study in this area showed negative results. As part of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network studies, 121 bipolar patients were treated with the omega-3 fatty acid EPA, 6 g daily vs placebo in a double-blind fashion for either bipolar depression or rapid cycling (

73). No difference between drug and placebo was apparent in either subgroup.

At this point, the utility of omega-3 fatty acids in treatment-resistant bipolar disorder is obscure. Further problems in the area include ignorance about which omega-3 fatty acids should be prescribed, in what proportion, at what dose, and the inability to ascertain the quality of the product since it is not FDA regulated.

Calcium channel blockers

A number of calcium channel blockers have been evaluated as treatments of acute mania and as maintenance treatments in bipolar disorder for over 20 years (

74). Results for verapamil are mixed at best. Although some studies showed preliminary positive results (

75,

76), other, better controlled studies demonstrated little efficacy (

77–

78). In the most recent report, 37 women, some of whom were pregnant, were treated with verapamil as monotherapy in an open fashion (

79). Manic or mixed syndromes responded better than depressive syndromes.

Individual calcium channel blockers differ in their affinity for the different calcium channel subtypes (

74). Thus, data for one agent may not generalize to the others. Additionally, verapamil may not penetrate the blood-brain barrier efficiently. Therefore, nimodipine, the most lipophilic calcium channel blocker with a greatest potential to enter the central nervous system, has also been evaluated in treatment-resistant bipolar disorder (

80). A first open case series of six acutely manic patients demonstrated some efficacy (

81). In the largest controlled study, 10/30 bipolar patients responded to nimodipine with moderate or marked improvement (

82). After the effective addition of carbamazepine to four treatment nonresponders, blind substitution of nimodipine verapamil led to an increase in manic symptoms, consistent with the differential effects of individual calcium channel blockers. In two patients, the blind substitution of isradipine, an agent more similar to nimodipine than verapamil, sustained clinical response.

Other agents

A number of other agents, suggested as effective antimanic agents or as maintenance treatments for treatment-resistant bipolar patients, have been the subject of small preliminary series. The most unusual of these was that of

d-amphetamine, which showed efficacy in doses of 60 mg daily in 5/6 acutely manic inpatients (

84).

Donepezil, a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, was evaluated in doses of 5–10 mg in 11 treatment-resistant bipolar I patients, 10 of whom were manic, hypomanic or mixed (

7). Six patients were markedly improved within 6 weeks, all at the 5-mg dose. No followup studies have emerged.

Mexiletine, an antiarrhythmic medication with additional anticonvulsant and analgesic properties, showed efficacy in doses of 200–1200 mg daily when given to 20 treatment-resistant or treatment-intolerant bipolar patients. (

8) Of the 13 completers, six (46%) were considered full responders, including all manic or mixed patients. A followup double-blind, placebo-controlled study by the same group evaluated mexiletine in 10 manic or hypomanic subjects (

85). Changes in YMRS scores favored mexiletine, but did not reach statistical significance.

Psychosocial adjunctive therapies

Of the treatments listed in Table 4, the most consistent and largest database has demonstrated the additive efficacy of a variety of psychological therapies in bipolar disorder. In all studies, medication plus a structured psychotherapy has been compared to medication plus a less structured psychotherapy or medication alone. Building on earlier studies (

86–

88) over the last 5 years, a variety of psychotherapy techniques have been evaluated, including family-focused treatment (FFT), cognitive therapy (CT), group psychoeducation, and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT). For all approaches, the addition of the structured psychotherapy added additional benefit, as measured by a variety of outcome variables, including longer survival time before relapse, fewer relapses, greater reductions in symptom rating scales, enhanced compliance, fewer days in mood episodes, improved social functioning, and fewer and shorter hospitalizations.

Family-focused treatment

Adapted from earlier studies on family interventions for schizophrenic patients, FFT is an amalgam of psychoeducation, communication skills training for dealing with intrafamilial stress and problem-solving skills (

89), administered as approximately a 20-session therapy over 9 months. Inherent in this treatment model is the need for at least one relative with whom the patient either lives or is in regular contact (four or more hours weekly). When compared to a control group (

n =70) that received two educational sessions and emergency counseling sessions as needed, patients (

n = 31) receiving FFT showed fewer relapses and longer time to relapse and greater improvement in depressive symptoms (but not manic symptoms) over one year (

90). Improvements were greatest among FFT patients whose families were high in expressed emotion, a construct composed of critical comments towards the patient and/or overinvolvement with the patient. A 2-year followup showed continuation of treatment effect with FFT patients experiencing fewer relapses (35 vs 54%, hazard ratio = 0.38), longer survival intervals (74 vs 53 weeks,

P =0.003), greater medication adherence and greater reduction in mood symptoms (

91). Medication adherence mediated positive effects on mania symptoms but not depressive symptoms.

Another study from the same group compared FFT (

n = 28) to a briefer individual therapy that was supportive, educational and problem-focused (

n = 25) (

92). Over the first year of followup, FFT demonstrated some weakly greater treatment efficacy compared to individual therapy. Over the 2-year study period (including 1 year of treatment and another year of followup) however, FFT was associated with significantly fewer total relapses and fewer hospitalizations.

Cognitive therapy

When combined with pharmacotherapy, individual CT administered in 12–18 sessions over the first 6 months with two booster sessions over the next 6 months (

n = 51) has also demonstrated efficacy in bipolar disorder compared to pharmacotherapy alone (

n = 52) (

93,

94). CT patients had fewer relapses at 12 months (75 vs 44%,

P = 0.004), fewer bipolar episodes (

P = 0.008), fewer days ill (

P =0.008) and fewer days in hospital (mean =10 vs 18 days,

P = 0.02). Significant additional benefits were seen in medication compliance, mean depressive symptom ratings and enhanced social functioning. At 2-year followup (after the original 6-month treatment period) differences between the two groups had faded over the last 18 months of followup, with overall effect of relapse reduction strongest during the first 12 months of treatment (

94).

Group psychoeducation

Group education with 8–12 patients per group was compared with nonstructured group interaction over 21 sessions in 120 remitted bipolar I and II patients in maintenance pharmacotherapy, followed over 2 years (

95). Fewer patients receiving group education relapsed (67 vs 92%,

P < 0.001). Numbers of depressions, manias, hospitalizations and days of hospitalizations were also significantly reduced.

Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy

IPSRT, an individual therapy derived from interpersonal therapy, focuses on resolution of interpersonal problems, prevention of future problems in these areas, the importance of maintaining regularity in daily routines, and the links between mood symptoms and the quality of social relationships and social roles (

96). IPSRT was compared to intensive clinical management (ICM), which focused on education, symptom and medication review and nonspecific support. In a study of 175 subjects with bipolar I disorder treated during an acute stabilization phase and then a two-year maintenance phase with subjects assigned to either the same or different treatment protocol during the two phases, IPSRT administered during the acute phase was associated with a longer time until a mood episode (

P = 0.01). This improvement was related to the increase in regularity of social rhythms (

P < 0.05). IPSRT administered during the maintenance phase did not show enhanced efficacy compared to ICM.

Combined psychotherapies

A combination of IPRST and IFIT for 1 year was significantly more effective than a control group (derived from the data of the earlier FFT study, (

90) in extending the time to relapse, with mean survival times = 43 vs 35 weeks (

P < 0.02), and in reducing depressive symptoms (

P < 0.0001), but not manic symptoms (

97).

Psychotherapy summary

The demonstrated efficacy of a number of different psychotherapies in decreasing mood symptoms, delaying time to relapse, and reducing hospitalization rates and days likely reflects some common positive effect of what, at first glance, seem like different treatment approaches. The clearest common elements of these psychotherapies are education and the development of more effective coping mechanisms. (Seemingly, the latter can be addressed through individual IPT-focused therapy CT, or family problem-solving approaches.) At this point, it would be impossible to suggest one psychotherapeutic approach over another. Group therapy would seem to be the most economical; family-focused therapy may be optimal for bipolar patients with intrusive, hostile families. The relatively weaker comparative efficacy data of IPSRT may reflect, among other factors, the strengths of the comparison treatment, which incorporated many effective psychotherapeutic principles.

Since few practitioners, especially physicians, are trained in any of the structured approaches just described, the efficacy of multiple approaches may indicate a set of core principles (as yet unidentified through research) for effective psychotherapy with bipolar patients. However, given some of the commonalities used in the therapies, experienced clinicians can consider adapting the principles and using them in a flexible manner, as is universal in nonresearch settings. The important principle, however, is that adjunctive psychotherapies add significantly (both statistically and clinically) to the efficacy of pharmacological treatment regimens.

Future directions

Systematic study of treatment-resistant bipolar disorder is still in its infancy. Beyond the consistent observation that SGAs in combination with either lithium or valproate are effective antimanic regimens, and that clozapine or ECT should be considered in refractory cases, the literature has little to guide clinicians. Owing to both proprietary concerns by pharmaceutical companies and the desire for hypothesis-driven and methodologically ‘correct’ studies, funding agencies shy away from the messy treatments regularly prescribed by clinicians. Although virtually all areas need more study, the three most vital are: combination treatments as maintenance therapy in bipolar disorder; the use of antidepressants, singly, in combination, with and without mood stabilizers for treatment-resistant bipolar depression; and maybe most important, techniques to enhance compliance, since rates of study completion in maintenance treatments of bipolar disorder are abysmally low. Finally, the psychotherapy data must be translated into clinically usable tools, focusing on techniques that are less manual driven and more adaptable to the realities of clinical practice.