HISTORY OF OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER

The recognition of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as a distinct mental disorder began in the 19th century. However isolated cases had been mentioned, two centuries earlier. In his cathartic and encyclopedic

Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), the melancholic Oxford Don, Robert Burton, quoted the case of a man who “If he be in a silent auditory, as at a sermon, he is afraid he shall speak aloud and unaware, something indecent, unfit to be said” (

1). Berrios (

2) relates how our 19th century professional forbearers gradually separated obsessions, in which insight was considered preserved, from delusions, in which it was not, and slowly distinguished compulsions from “impulsions,” which included various paroxysmal, stereotyped, and irresistible behaviors.

In the 19th century, the etiology of OCD was variously attributed to disorders of the will, the emotions, or the intellect. While French psychiatry favored causation anchored in emotive and volitional defects, German psychiatry postulated a defect of intellect. In 1877, the German psychiatrist Westphal used the term Zwangsvorstellung (compelled presentation or idea) to describe OCD psychopathology. The British translated Westphal's term as “obsession” and the Americans as “compulsion.” Our current diagnostic label, obsessive-compulsive disorder, was subsequently adopted as a compromise.

In the early 20th century, Freud developed the psychoanalytic theory of the etiology of OCD: faced with conflicts between unacceptable, unconscious sexual or aggressive id impulses and the demands of conscience (superego) and reality, the patient's mind regresses to concerns with control and to modes of thinking characteristic of the anal-sadistic stage of psychosexual development. The ambivalence characteristic of this stage produces pervasive doubting, and the stage's magical thinking leads to superstitious compulsive acts. The imperfect success of ego defense mechanisms—intellectualization, isolation of affect, undoing and reaction formation—gives rise to anxiety, preoccupation with contamination or morality, and fears of acting on unacceptable aggressive or sexual ideas, urges, or images (

3).

In the mid-20th century, two learning theory concepts began to be used to explain the development of OCD. The first concept was that of classical conditioning—a neutral stimulus paired with an anxiety-provoking unconditioned stimulus gains the power to evoke anxiety. Thus, the initially neutral sight of stove knobs is paired by an OCD checker with the unconditioned (albeit learned) idea of a house fire and now evokes anxiety. The second concept was negative reinforcement—new behaviors are learned and maintained because they reduce the anxiety elicited by the conditioned stimulus (

4). Thus, the checker repeatedly checks to be sure that the stove knobs are in the “off” position because doing so reduces anxiety.

In recent years, technology has facilitated the creation of biological theories regarding the etiology of OCD. Their conceptual elements range from genetic risk factors and dysfunctional serotonergic, dopaminergic, and glutaminergic neural circuits to autoimmune responses to streptococcal infection (

3,

5). Undoubtedly, these biological theories will soon benefit clinical practice further.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

A Canadian epidemiological study in which a trained nurse interviewer was used to investigate possible OCD cases identified by lay interviewers estimated the

1-month prevalence of OCD in adults to be 0.6% (

9). The estimated

12-month prevalence in adults ranges from 0.6% to 1.0% (

10,

11). The lifetime prevalence is estimated to be 1.6% (

11). In a large epidemiological study (as contrasted with studies of individuals coming for treatment), the median age of onset of OCD was 19 years, but 21% of cases began by age 10 (

11). Although the age of onset is generally lower in males than in females (

12), by age 18 years, epidemiological studies report a slight preponderance of females (

13). Most studies reported no difference in prevalence across socioeconomic strata.

The natural history and course of OCD have not been firmly established. Conclusions are limited by differing sampling methods, diagnostic criteria, criteria for improvement, variable intervening treatments, and reliance on subjects' memories of distant events. A large (N=144) study suggested that over 40 years or more, nearly half of patients will experience clinical recovery (no clinically relevant symptoms for ≥5 years), but only 20% will experience full remission (no symptoms in the previous 5 years) (

14). An episodic course of symptoms (≥6 months of full remission) has been reported in from 2% (

15) to 27% (

16) of patients. A deteriorative course has been reported in 8% (

14) and 10% (

15) of patients. No large, long-term follow-up studies of subjects with OCD identified in community surveys have been published. The course of such subjects may differ from that of individuals who seek treatment.

ASSESSMENT

Patients seeking treatment for other psychiatric disorders may hide their co-occurring OCD. For example, a study of psychiatric diagnoses recorded for 1.7 million persons aged 6–65 years treated within a California health maintenance organization (

17) showed a much lower 1-year prevalence of OCD (0.084%) than the rates reported for epidemiological studies. Thus, screening of patients with disorders that are often associated with OCD, such as mood disorders, other anxiety disorders, and tic disorders, may be helpful. Screening questions might include: Do you have troubling thoughts or ideas that you cannot put out of your mind? Do you have to wash your hands or check things repeatedly? Are you frequently bothered by moral or religious questions that will not go away? Do you have trouble discarding things?

To assess the patient's symptoms, the clinician may wish to use the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) Symptom Checklist, which lists 40 obsessions and 29 compulsions. The 18-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (

18) is a shorter alternative. The 10-item Y-BOCS scale (

19,

20), which evaluates the severity of obsessions and compulsions separately, is the standard scale used in treatment outcome studies. The rater rates obsessions and compulsions in terms of the time occupied, how much they interfere with functioning, the patient's degree of distress, and his or her attempts to resist symptoms and the frequency of success. The Y-BOCS scale and checklist along with instructions for their use are available at

http://apple.cmu.edu.tw/∼u901039/Rating-Scale-YBOCS.pdf. In clinical practice, some clinicians measure symptom change by simply asking the patient to estimate the amount of time taken by symptoms in an average day in the past week.

OCD substantially diminishes patients' quality of life (

21) and includes an increased risk of suicide attempt (

22,

23). Thus, a careful evaluation of the potential for self-injury is important. Helpful guidelines are available elsewhere (

24). Thoughts, images, or urges related to harming others are a common symptom in OCD (

3), and a patient can be deeply worried about loss of control. It may be helpful to inform the patient that such obsessions are common and that, despite the fear of losing control, acting on such thoughts or urges has not been reported in patients with OCD. OCD symptoms can lead to inadvertent harm to others when, for example, a parent cleans children with harmful substances such as bleach or neglects them because of time spent in compulsive behaviors.

In addition to assessing the patient's symptoms, their effects on well-being and functioning, and the presence or history of comorbid conditions, it is helpful to establish the reason for seeking treatment. What does this patient

want and

expect and

why? How are these expectations colored by past treatment experiences, beliefs about OCD, the patient's culture, and his or her family's views? How much insight does the patient have into the irrationality of the symptoms and how much motivation to confront them? The other standard elements of a psychiatric workup (

25) from chief complaint through medical history, medication history (including over-the-counter preparations), family and social history, and mental status examination may also provide data helpful in treatment planning. Have drug doses and the trial durations been adequate? Which side effects occurred and what degree of benefit? Has the patient had an adequate trial of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), and, if so, with what results? What medical conditions or concurrent medications, with their potentials for drug interactions, need to be taken into account (

26,

27; see also the federal National Library of Medicine by entering “pubmed” in a search engine, or Web sites such as

hppt://medicine.iupui.edu/flockhart or

hppt://mhc.com/Cytochromes)? What is the nature of the patient's primary support group? Are the group members helping to maintain symptoms or exacerbating them? Can they facilitate treatment?

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Obsessions and compulsions must be differentiated from similar symptoms that occur in other disorders. In contrast with obsessions,

depressive ruminations usually drag the patient into the past, where self-criticism, guilt, and regret dominate the mental landscape; when the focus is the future, it is a place of futility, where attempts to improve life will certainly fail. Depressive ruminations do not motivate mental or behavioral compulsions. The

worries of generalized anxiety disorder relate to real-life problems, such as plausible accidents or illnesses striking a loved one, mistakes or contretemps at work, or potential but unlikely financial difficulties. Although the individual may inappropriately check that a loved one is safe, other compulsive behaviors are not characteristic. In

posttraumatic stress disorder, the intrusive thoughts and images recreate actual traumatic events, whereas in OCD the ideation concerns possible future events. The bizarre delusional ruminations and odd stereotyped behaviors occasionally seen in

schizophrenia are accompanied by the disorder's diagnostic hallmarks. However, obsessions and compulsions due to comorbid OCD also occur (

28), either spontaneously or as a side effect of treatment with second-generation antipsychotic drugs (

3). The content of comorbid OCD obsessions and compulsions is not bizarre and is that seen in pure OCD, i.e., contamination, aggressive impulses, somatic symptoms, and sexuality. The patient will often have insight into the irrationality of these symptoms despite lacking insight into the schizophrenic symptoms (

29).

The

hypochondriac's fear or belief that he or she has a serous disease stems from misinterpreting benign bodily signs or symptoms, whereas in OCD these fears arise from external stimuli, e.g., exposure to “contamination.” A recent study showed that chest pain, other pain complaints, palpitations, dizziness, and headache are more common primary fears in hypochondriasis than in OCD (

30). The preoccupations of

body dysmorphic disorder are limited to concerns about disturbing but nonexistent or slight physical defects. The intrusive thoughts and irrational behaviors of

anorexia nervosa and

bulimia nervosa concern food intake, calories, and weight and their implications for self-esteem.

Post-partum depression can produce repeated urges to harm the infant that may be acted upon. In OCD these urges, while sources of torment, are not accompanied by depressed mood, are ego-dystonic, and are always resisted.

The

complex vocal or motor tics of Tourette's disorder may closely resemble compulsions and may take the form of ordering, arranging, or touching objects or the self. Tics are not, however, aimed at relieving anxiety or preventing unwanted events, nor are they preceded by related ideation (

31). Having to repeat an action to obtain a “just right” feeling may be a compulsion or a tic or contain elements of both. In individuals with a personal or family history of tics, comorbid attention deficit disorder, or learning disorder, the behavior is more likely to represent a complex tic than a compulsion (

32).

OCD and

obsessive-compulsive personality disorder may co-occur, although this is not the most common comorbid personality disorder in patients with OCD (

3). Hoarding may be seen in both disorders, but the need for control, preoccupation with details and rules, perfectionism, and moral inflexibility characteristic of the personality disorder are ego-syntonic and pervasive, rather than ego-dystonic and limited to specific content areas as in OCD.

ETIOLOGY AND NEUROBIOLOGY

No environmental risk factors have been established for OCD. In one series of 200 patients, the 29% who felt that their illness had been triggered by an event most often cited increased responsibility or significant loss (

15). However, an early onset form marked by abrupt onset and co-occurring tics may be associated with an autoimmune reaction to streptococcal infection. The exact mechanisms giving rise to this form, termed pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection, are under study (

39,

40).

Imaging studies by many investigators have led to the hypothesis that OCD results from dysfunction in a cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit that links the orbital frontal cortex, cingulate gyrus, striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), globus pallidus, thalamus, and a return to the frontal cortex (

41). Pretreatment studies of symptomatic patients, studies of patients challenged with feared stimuli, and studies of treatment effects all support this model (

42), although some inconsistencies in results exist, possibly due to methodological differences (

43). The results of neurosurgical interruption of this circuit also support this model (

44).

A role for dysfunction in serotonergic pathways is supported by the effectiveness of SRIs. That their therapeutic effect is often modest leaves room for contributions by other systems. Denys et al. (

45) have summarized preclinical and clinical evidence suggesting a role for dopaminergic neurons. More recently, the results of magnetic resonance imaging spectroscopy studies, genetic studies, and a study reporting elevated glutamate levels in cerebrospinal fluid have given rise to speculation that glutamatergic hyperactivity may contribute to the pathophysiology of OCD (

46,

47).

Family studies and twin studies show higher concordance for OCD among monozygotic than dizygotic twin pairs, indicating a genetic contribution to the etiology of OCD (

5). A meta-analysis of five family studies with adult probands reported that first-degree relatives of subjects with OCD were four times more likely to have OCD than those of control subjects (

48). Searches for genetic loci closely tied to OCD are underway, but no genetic locus indisputably linked to OCD pathogenesis has been identified.

A number of neurological conditions can induce subclinical or clinical OCD. The involvement of damage to the brain regions that are hyperactive in OCD imaging studies gives credence to the current pathophysiological models of OCD (

49). The neurological conditions associated with OCD include brain trauma, stroke, encephalitis, temporal lobe epilepsy, neuroacanthocytosis, Sydenham's chorea, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, Prader-Willi syndrome, and poisoning by carbon monoxide or manganese (

3,

50,

51). Onset of OCD after age 50 should raise suspicion of a neurological cause (

52).

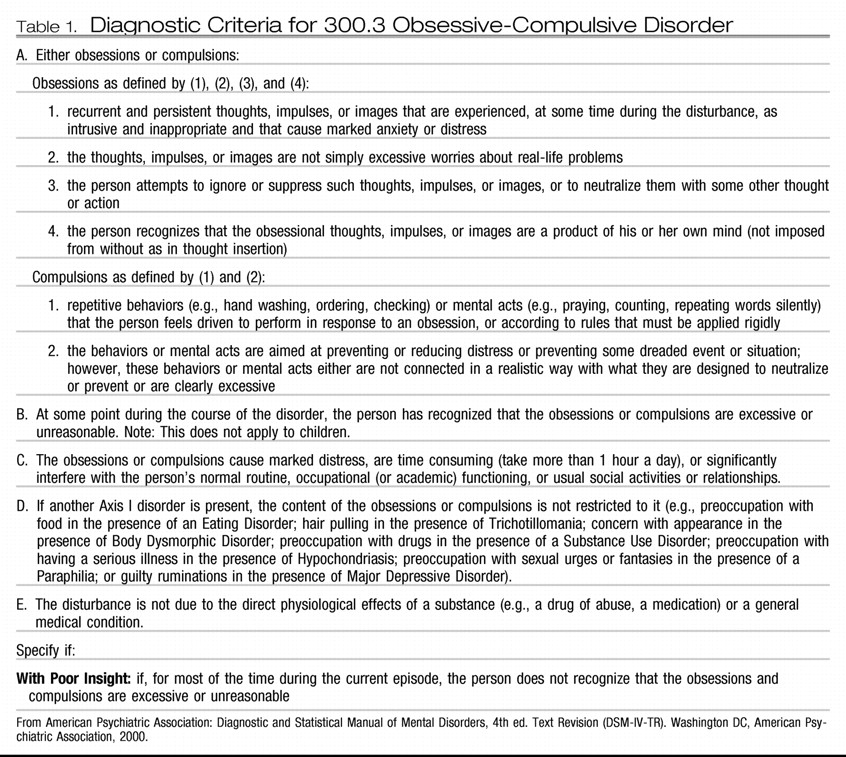

TREATMENT—EXPECTATIONS AND FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN INITIAL PLANNING

Treatment of OCD is challenging, as few patients are cured, although many patients can be helped greatly (

53). Clinical trials indicate that both CBT in the form of exposure and ritual (or response) prevention (ERP) and SRIs are safe and effective first-line treatments for OCD (

3,

54,

55). Still, they rarely bring complete symptom relief (

56). A recent meta-analysis reported the results of nine SRI trials, with a mean duration of 9.6 weeks, and four CBT trials, with a mean of 16 treatment sessions delivered over 10.2 weeks (

57). Among the intent-to-treat samples, “response,” conventionally defined as a 25%–35% decrease in Y-BOCS or NIMH-Obsessive Compulsive scale scores, occurred in a mean of 52.5% of subjects in the SRI trials; improvement by 25%–50% on OCD outcome measures occurred in 25%–75% of subjects in the CBT trials. The SRI trials did not report “recovery” rates. With use of a Y-BOCS score ≤8 or ≤12 with at least a 6-point decrease, three CBT trials reported recovery rates of 22%–33%. Not surprisingly, some patients find particular medications intolerable, as do some who consider or start CBT. For example, one CBT review noted that at least 25% of patients could not cooperate with ERP (

58).

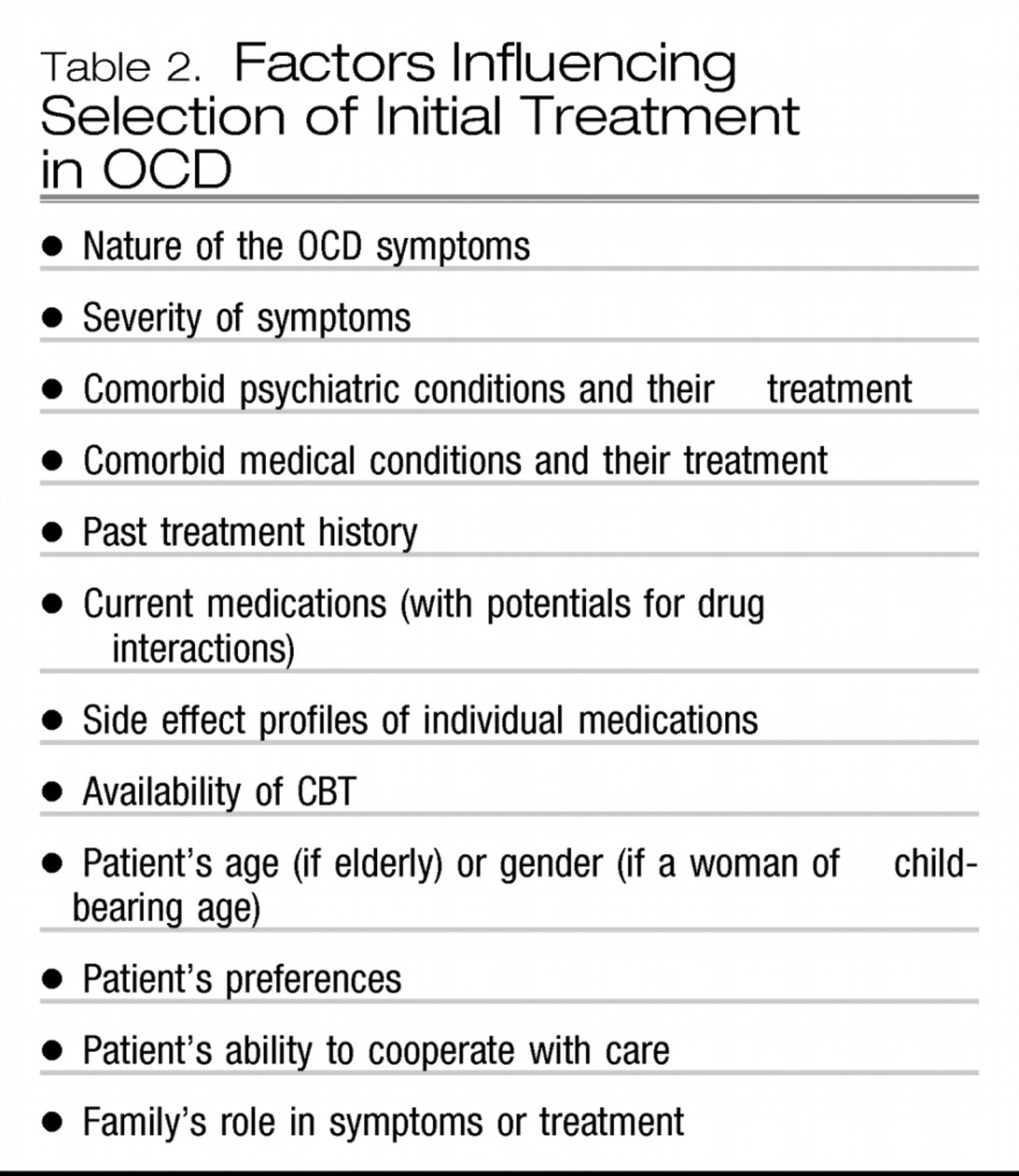

A number of factors (

Table 2) will influence the choice of a treatment setting and the initial treatment approach (

59). For example, hospital treatment may be needed for those with a risk of suicide, an inability to tolerate outpatient medication trials, or a need for intensive CBT. Residential treatment may be needed for those requiring multidisciplinary treatment with close monitoring (

60). Partial hospitalization may be needed for those requiring daily CBT, medication monitoring, and adjunctive psychosocial treatments (

61). Symptoms of hoarding or fears of contamination that prevent the patient from leaving home may require home-based treatment. In most cases, however, initial treatment can be conducted on an outpatient basis. Whatever the setting, working to enhance the treatment alliance is important, especially by educating the patient and family about the nature of OCD and about the available treatment (Appendix in reference

59). The web sites of the Obsessive Compulsive Foundation (

http://www.ocfoundation.org) and the Obsessive Compulsive Information Center (

http://www.miminc.org) are helpful educational resources.

Unfortunately, one cannot accurately predict at treatment outset which treatment will benefit or adversely affect a particular patient (

62,

63). Severe depression or anxiety can interfere with a patient's ability to cooperate with the behavioral homework usually required in CBT (

58,

64). Onset in childhood, longer duration of illness, and, in some studies, diminished insight or hoarding, which may be a neurobiologically distinct form of OCD (

65,

66), have been associated with poorer response to SRIs (

63). Other OCD symptoms or symptom dimensions (symmetry/ordering, contamination/cleaning, aggressive/checking, and sexual/religious) (

67) have not been consistently related to treatment outcome and may change over time in a given patient (

68). Treatment response is independent of gender, but women may experience premenstrual worsening of OCD symptoms (

69,

70). The prevalence of slow, normal, extensive, and ultrarapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 varies with ethnicity and may contribute to the probability of adverse events affecting compliance and hence outcome (

71). For example, poor metabolizers via CYP2C19, whose clomipramine dose should be only about 60% of the average recommended dose, comprise 13%–23% of Asians but only 2%–5% of Caucasians (

71).

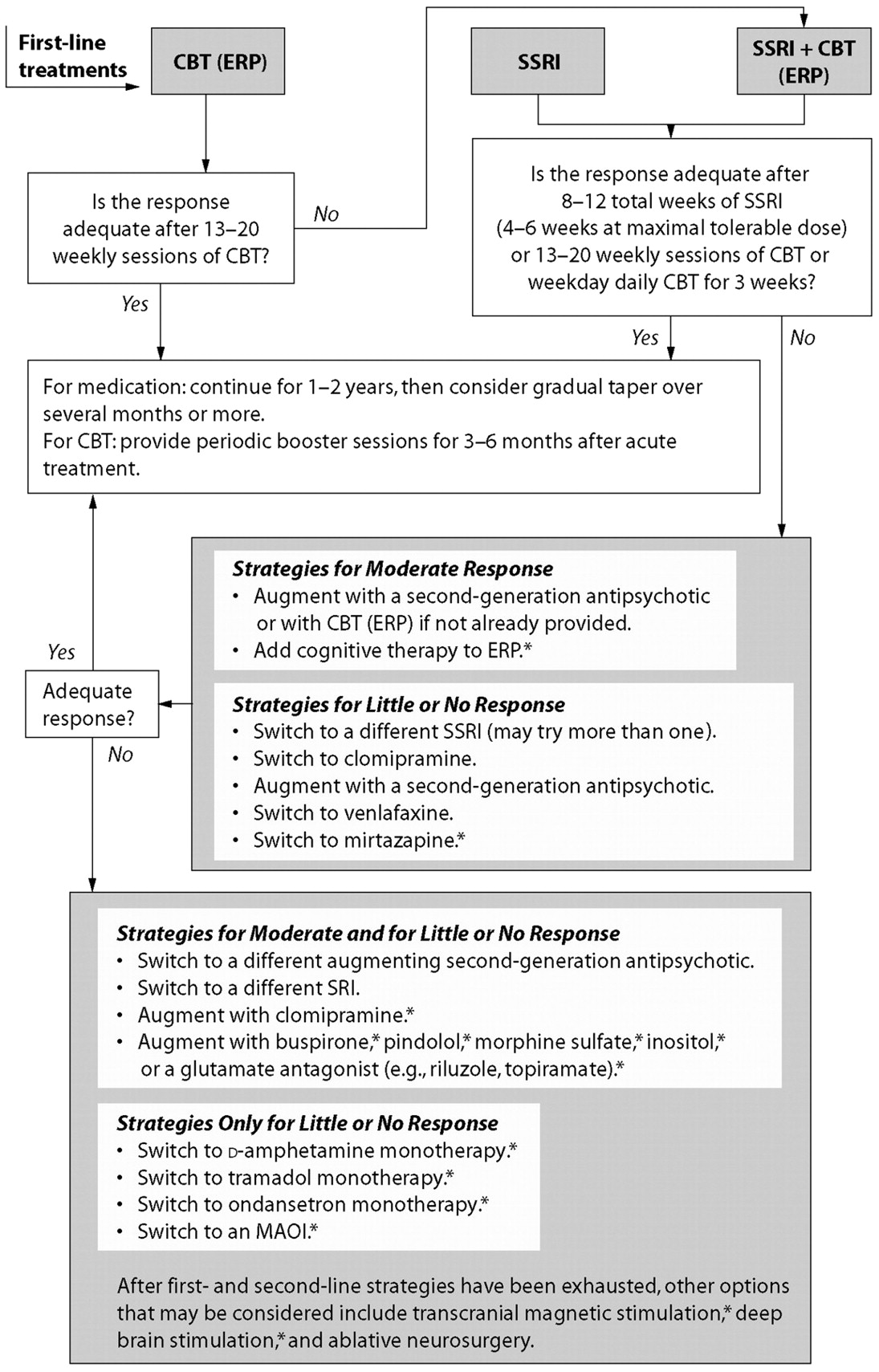

The APA Practice Guideline for Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (

59) provides an algorithm for selecting sequential treatment steps that is based on expert review of the available data (

Figure 1). An SRI alone would be a reasonable initial treatment for a patient who has responded to a given drug in a previous trial, one unable to cooperate with CBT, or one preferring this treatment. ERP would be indicated for a patient who prefers to avoid medications and is willing to do the work of ERP. Combining an SRI and ERP may be more effective than monotherapy for some patients (

72) and would be considered when monotherapy produced an inadequate response, when SRI treatment is indicated for a comorbid condition, and for patients with severe symptoms.

The presence of comorbid psychiatric conditions may also influence treatment strategies. Unfortunately, no large controlled trials have been conducted to determine the best treatment methods in these situations. The available evidence suggests the following approaches. SRI treatment may be effective for both OCD and co-occurring major depression, which usually does not adversely affect the OCD response to SRI treatment (

73). Appropriate treatment of co-occurring major depression (

74,

75) may, however, require modification of the OCD treatment plan. If depression is the dominating disorder, arranging CBT, interpersonal therapy, or short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for the depression should take precedence over arranging ERP for the OCD. For treatment-resistant depression, a drug switch or augmentation with bupropion, lithium, thyroid hormone, buspirone, or lamotrigine may be indicated (

76,

77). With a switch of SRIs, however, there is the risk of losing the OCD response. OCD complicated by dysthymia might be treated initially with an SRI, as both conditions may respond, or with an SRI plus ERP (

37).

When bipolar disorder or a history strongly suggestive of bipolar disorder is present, this condition must be considered first (37). Because ERP treatment of OCD has no risk of inducing hypomania or mania, this treatment should be strongly considered. Before initiation of SRI treatment, steps must be taken to stabilize the patient's mood with lithium, an anticonvulsant, or a second-generation antipsychotic drug (

78,

79). Because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have a lower risk of inducing mania, an SSRI would be preferred over clomipramine or venlafaxine for the OCD (

80). Potential drug interactions must be considered.

Co-occurring panic disorder may respond to an SRI (

81) or to CBT designed for this disorder (

82). SRIs should be started at a low dose in patients with current or past panic disorder to avoid reigniting or exacerbating panic attacks. Alternatively, one may start an SRI and a benzodiazepine simultaneously and gradually taper the benzodiazepine after the first 4–6 weeks (

81). Social anxiety disorder may also respond to the SRI used for OCD (

83), among other possible treatments.

SRIs are usually well tolerated in patients with comorbid schizophrenia (

84). Case reports of psychotic exacerbation exist, however (

3). Transient or persistent obsessive-compulsive symptoms may be induced in schizophrenic patients by second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Case reports suggest that persistent symptoms may respond to addition of an SRI (with attention to potential drug interactions), to switching antipsychotic drugs, or to adding CBT.

Treating comorbid alcohol or substance abuse or dependence takes precedence over treating OCD because these disorders bring risks of drug interactions and poor OCD treatment adherence. Several organizations have published treatment guidelines (

85,

86).

In the presence of chronic motor tics (

87) or Tourette's disorder (

88), OCD unresponsive to SRI monotherapy may respond to the addition of antipsychotic drugs, but they are not always required (

89).

Reports in the literature with regard to the impact of comorbid personality disorders on the outcome of pharmacotherapy and CBT for OCD are mixed (

90–

93). Passive-aggressive personality traits and borderline personality disorder have compromised treatment adherence in reported cases (

93,

94).

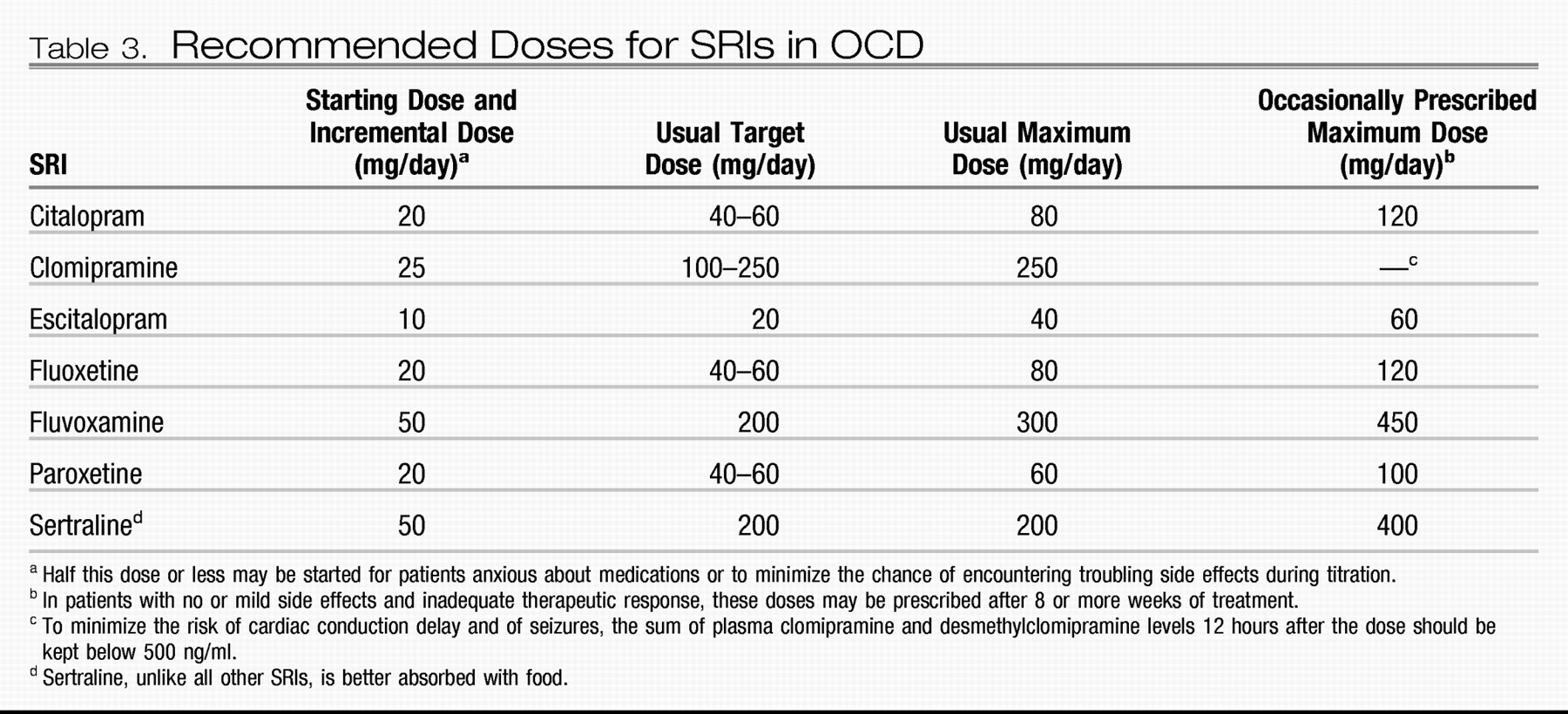

TREATMENT—INITIAL DRUG CHOICE AND DOSING

The SRIs, clomipramine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline, are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of OCD. Large, double-blind, European trials indicate that citalopram (

95) and escitalopram (

96) are also safe and effective. Meta-analyses of placebo-controlled trials (

57,

73) suggest that clomipramine is more effective than fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, or sertraline, but head-to-head comparison trials have found no significant difference (

59). The less troublesome side effect profile of SSRIs makes their use preferable for a first medication trial.

For unknown reasons, individual patients may respond more fully to one SRI than to another, but no SSRI is more effective than any other on a population basis. After a failure to benefit from a first SRI trial, the likelihood of a response to a second SRI trial seems undiminished. The likelihood of a response to a third or subsequent SRI trial is unknown. Results from available studies differ widely with regard to the distribution of the number of previous trials in which drug treatment had failed, information about the adequacy of prior trials, definitions of response, and subjects' clinical characteristics. Response rates, i.e., attaining a ≥25% decrease in Y-BOCS score or a Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale rating of much or very much improved, are, however, distressingly low among treatment-experienced subjects in some studies (

97,

98).

In view of their equal likelihood of efficacy, choice of an SSRI is influenced by potential drug interactions, side effects, past treatment response, and co-occurring medical conditions and their treatments:

•.

Fluvoxamine, an inhibitor of the liver cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP1A2, would be contraindicated in a patient requiring theophylline or warfarin and could make a person who consumes caffeine drinks (coffee, tea, colas) jittery.

•.

Fluvoxamine also inhibits CYP3A4, which metabolizes benzodiazepines and certain calcium channel blockers and antiarrhythmic drugs.

•.

Fluoxetine and paroxetine are strong inhibitors of CYP2D6, which metabolizes many antiarrhythmics, antipsychotics, β-blockers, and the opiate prodrugs, codeine and hydrocodone, that are ineffective unless metabolized by CYP2D6 to active analgesics.

•.

Citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline (as well as mirtazapine and venlafaxine) have few or no troublesome drug interactions. However, any of the SSRIs may induce serotonin syndrome if added to a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, tramadol, meperidine, or dextromethorphan (

99).

•.

As the most anticholinergic SSRI, paroxetine would not be the initial choice for patients with constipation or urinary hesitancy.

•.

The SRI clomipramine is still more anticholinergic, and its adrenergic blockade may produce orthostatic hypotension and postural dizziness.

Before starting an SRI, the clinician should inform the patient that significant symptom reduction often takes 6–8 weeks and can sometimes take 10–12 weeks. The clinician should describe common side effects and encourage the patient to call if questions or troubling side effects arise. These steps will facilitate adherence and help build the treatment alliance. Expert recommendations regarding the dosing of SRIs in OCD are shown in

Table 3 59.

Elderly patients should usually receive lower starting doses and more gradual dose titration to avoid side effects. Starting clomipramine at ≤25 mg/day will increase its tolerability in all age groups (

100). Higher SSRI doses appear to induce modestly higher response rates and greater magnitudes of symptom reduction (

101–

104). In a fluoxetine open-label continuation trial (

105) and in a double-blind sertraline trial (

106), some subjects who had not responded to the manufacturer's highest recommended dose responded to higher doses than these. Because substantial clinical benefit is usually slow to appear and higher doses may be more effective, some clinicians titrate doses upward weekly as tolerated to the maximum recommended dose rather than waiting 4–8 weeks at each dose to evaluate the response.

Despite the evidence suggesting greater benefit from higher SRI doses, OCD outcome is not related to plasma levels of fluvoxamine (

97), sertraline (

102), fluoxetine (

107), or clomipramine (

108). Plasma levels, apparently, do not reflect drug concentrations at the sites of action in the brain.

TREATMENT—MANAGING COMMON SRI SIDE EFFECTS

Starting with low SRI doses will minimize early queasiness or nausea, which, if mild, will usually remit within 1–2 weeks at a constant dose. Morning dosing and standard sleep hygiene measures will reduce the chance of insomnia, but a sleep-promoting agent may be required. Modafinil may be used to offset daytime fatigue or sleepiness (

109). Excess sweating may respond to low doses of benztropine (

110), clonidine (

111), cyproheptadine (

112), or mirtazapine (

113). Sexual side effects, including diminished libido and difficulties with erection or orgasm, affect one third or more of patients (

114). The “drug holiday” approach may help with the latter symptoms (

115) but should not be attempted with paroxetine or venlafaxine because of possible withdrawal symptoms nor with fluoxetine because of its long half-life. Dose reduction may aid some patients, but the risk with this strategy is that the therapeutic effect may be diminished. Addition of bupropion was modestly effective in one double-blind study (

116), but not in another (

117). Addition of buspirone was effective for women in a double-blind trial (

118). In controlled trials, sildenafil and tadalafil have restored erection in men (

119); sildenafil has restored orgasmic ability in both men (

120) and women (

121). Other antidotal strategies, e.g., addition of amantadine, stimulants, yohimbine, or ropinirole, are supported only by case series or uncontrolled studies (

122,

123). Suggestions for managing less common side effects are summarized elsewhere (

3).

TREATMENT—CBT

The effectiveness of CBT in the form of ERP is well supported by controlled trials (

55,

57). Some studies also support CBT using primarily cognitive techniques if these are combined with behavioral experiments testing the patient's dysfunctional beliefs (

124,

125). These beliefs include magical thinking, perfectionism, an exaggerated sense of responsibility for feared events, moral equivalency of thoughts and actions, and the need to control one's thoughts. Although other psychosocial treatment methods have been proposed, e.g., the “brain-lock technique” (

126) and acceptance and commitment therapy, they have not been studied in controlled trials.

CBT has been conducted in many formats—individual, group, family and even a computer-based touch-tone telephone method (

127–

130). Sessions vary in length from 1 to 2 hours, but some evidence suggests that sessions of 90–120 minutes are more effective than shorter sessions (

131). The literature and expert opinion (

132) suggest that 13–20 weekly sessions is an adequate trial for most patients. Postgraduate training in CBT for OCD is encouraged for psychiatrists who wish to provide this treatment. Several treatment manuals are available (

133–

135). Motivated patients can also be referred to a psychologist skilled in CBT for OCD. To enhance compliance, the clinician should explain the nature of the treatment, the rationale for treatment steps, and the patient's responsibilities. Self-help treatment guides (see Appendix in reference

59) and support groups (accessible through the Obsessive Compulsive Foundation) may also be useful, but have not been evaluated in controlled trials.

In ERP, the therapist helps the patient create a list of items or situations that are avoided because they evoke obsessions or compulsions. The list is then rearranged from least to most anxiety-provoking. Asking the patient to rate each item on a scale from 1 to 100 subjective units of distress may be helpful. The therapist coaches the patient in arranging prolonged exposure to feared situations or items, beginning with one that evokes significant but tolerable distress. The exposure may be in vivo (touching “contaminated” doorknobs) or in imagination (imagining a burglary because of an unlocked door). Daily, repeated exposures, and refraining from performing the related rituals, i.e., allowing the elicited anxiety to extinguish, is prescribed, until the exposure elicits mild or no anxiety. The therapist helps the patient move through the hierarchy of feared items quickly enough to prevent loss of faith in the treatment, but slowly enough to allow adherence.

TREATMENT—STRATEGIES FOR PARTIAL, LITTLE, OR NO RESPONSE TO FIRST-LINE TREATMENTS

The APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (

59) lays out sequential strategies (

Figure 1) for partial, little, or no response after a series of trials of the first-line treatments described above. “Partial” response is defined as “clinically significant but inadequate” response. Note that a first-line pharmacotherapy trial should be continued for as many as 12 weeks and a CBT trial for at least 13 weekly sessions before one concludes that the response is inadequate. None of the subsequent strategies is supported by definitive trial data. Less complex algorithms exist. For example, the algorithm created by the British National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (

136) recommends against the use of venlafaxine in OCD and omits many treatments having limited supportive evidence.

The APA Practice Guideline algorithm for OCD (

Figure 1) indicates that in patients with a partial but inadequate treatment response after at least 12 weeks of SRI therapy, augmentation might be preferred to switching drugs. Double-blind, placebo-controlled augmentation trials suggested that approximately 40% of patients will experience a ≥25% decrease in Y-BOCS score within 4 weeks of the addition of risperidone 0.5–2.0 mg/day, olanzapine 5–20 mg/day, or quetiapine≥300 mg/day (

137,

138). Augmentation with haloperidol may be more effective in those with than in those without co-occurring tic disorders (

87). Optimal dose, long-term tolerability, and optimal treatment duration remain unknown. A small study reported that >80% (15 of 18) patients had a relapse within a few months of discontinuing successful augmentation with an antipsychotic drug (

139).

Augmenting SRIs with ERP (

140,

141) or vice versa (

142) is supported by modest evidence, but the studies have notable methodological limitations. A smaller database supports adding cognitive therapy to ERP.

Switching SRIs for little or no response has been discussed above. A double-blind study supports switching to venlafaxine, but only at doses of 225–300 mg/day, and the response rate was low (19%) (

143,

144). A double-blind comparator trial, however, showed that venlafaxine 225–350 mg/day was as effective as clomipramine 150–225 mg/day (

145), but the mean dose of clomipramine was modest (168 mg/day). Results of a small study with an open-label phase followed by double-blind discontinuation supported a switch to mirtazapine 60 mg/day after failure to respond to one SRI (

146).

After these strategies have been exhausted, the remaining strategies in the APA guideline are supported by one or a few small trials, uncontrolled case series, or case reports. Expert opinion (

132) and open-label trials (

147–

150) supported augmentation of SSRIs with low-dose clomipramine. Total plasma concentrations of clomipramine and desmethylclomipramine should be kept below 500 ng/ml to reduce the risks of seizures and cardiac arrhythmias. A screening electrocardiogram and pulse rate and blood pressure monitoring would be reasonable precautions for patients older than age 40 or suspected of having heart disease. Results of controlled trials of lithium and buspirone augmentation were negative despite the promise of case reports, and a large placebo-controlled trial failed to confirm the efficacy of St. John's wort (

151). Results of one small, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pindolol augmentation, 2.5 mg three times daily were positive after 4 weeks (

152), but results of a second trial were not (

153). Augmentation with once-weekly oral morphine sulfate 30–45 mg was superior to placebo in a small, double-blind crossover trial (

54), and monotherapy with the weak narcotic agonist, tramadol, is supported by case reports and a case series (

155). Substantial reduction of OCD symptoms was reported in two small, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-dose studies of dextroamphetamine 30 mg (

156,

157). However, given their abuse potential, trials of narcotics and stimulants should be avoided in patients with OCD judged to be vulnerable to substance abuse or dependence.

An open-label case series examining SSRI augmentation with lamotrigine up to 100 mg/day reported improvement in only one of seven patients treated for at least 4 weeks (

158). Studies of inositol 6 g three times daily have produced mixed results. A small but significant effect compared with placebo was reported in a double-blind crossover study (

159), but inositol augmentation of SSRI treatment in another study brought no benefit (

160); 3 of 10 subjects in a third (open) augmentation trial had a clinically significant response (

161). A double-blind crossover trial in which gabapentin up to 3600 mg/day was added to fluoxetine (

162) failed to confirm positive results of an open trial (

163).

With regard to glutamate-modulating drugs, positive case report results exist for augmentation of SSRIs with memantine (

164,

165) and

n-acetylcysteine (

166), with topiramate in two case series (

167,

168), and with riluzole in an open (and methodologically compromised) trial (

169).

Expert opinion does not support the use of ECT for treating OCD (

59,

132), although it may be indicated for co-occurring conditions such as major depression (

74). Controlled trials of ECT for OCD have not been conducted, and the available data (

170) are consistent with the interpretation that the limited benefit resulted from reducing the exacerbation of OCD by the comorbid depression.

Ablative neurosurgery in the form of anterior cingulotomy, anterior capsulotomy, subcaudate tractotomy, and limbic leucotomy has been used for patients with severe OCD refractory to all first-line treatments and to many of the subsequent interventions just reviewed. Improvement has been reported in from 35% to 50% of patients (

171,

172), but the evaluations have not been performed in a blinded manner, and patients have often received new or continued treatment after surgery. Serious adverse consequences appear to be uncommon, but include apathy, affective blunting, personality change, seizures, transient or persistent urinary dysfunction, and transient mania (

44). Deep brain stimulation is a potentially promising alternative to ablative neurosurgery, attractive in part because it is reversible. Only a few case series and case reports exist (

44,

173), but some have involved double-blind evaluations. In small trials, transcranial magnetic stimulation has generally been ineffective in OCD, but further exploration of varying techniques is underway (

44,

173).

DISCONTINUING TREATMENT

Expert opinion recommends continuing successful pharmacotherapy for 1–2 years before considering gradual tapering (

59,

174,

175). In follow-up studies, rates of relapse or discontinuation for insufficient clinical response after a double-blind switch to placebo vary widely across studies, in part because of differences in study design and definitions of relapse, but in all studies, relapse rates are unacceptably high, from 24% within 28 weeks to 89% within 7 weeks (

104,

176–

178). Until more is known about preventing relapse, most patients should receive continued treatment unless good reasons for discontinuation arise.

Expert opinion recommends supplementing a successful course of ERP with monthly booster sessions for 3–6 months (

59,

132). Methodologically limited studies of relapse after ERP suggest that a majority of patients may do well 2 years after treatment. One study comparing ERP, cognitive therapy, and their combination with clomipramine showed a majority of those who had completed a treatment trial to be doing well 5 years later (

179). Because study patients are not representative of all patients with OCD and because patients in follow-up studies receive variable treatment during follow-up, these results cannot be confidently extrapolated to OCD patients seen in ordinary clinical practice. Educating patients about relapse prevention after ERP appears to decrease the risk of relapse (

180). One study showed that relapse rates 3 months after discontinuation of intensive ERP were significantly lower than those after discontinuation of an SRI (

181). However, the extent and durability of any differences in relapse rates between SRI- and ERP-treated patients cannot be firmly derived from the available studies because of, among other methodological problems, differences in subjects studied, intensity of treatment, relapse criteria, length of observation, and treatments received during follow-up (

57). For example, a study examining nine different relapse definitions applied to data from a single trial produced relapse rates of from 27% to 63% for clomipramine and of from 0% to 50% for intensive ERP (

182). Uncontrolled follow-up studies suggest but do not prove that combining ERP with an SRI may delay relapse when the SRI is discontinued (

181,

183). At the present time, long-term treatment and gradual reduction in treatment intensity, if reduction is desired, would be prudent for most patients.