CREATION OF THE DOCTOR-PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

A psychiatrist does not owe a professional duty of care to a person as a patient unless a psychiatrist-patient relationship exists. Once that relationship is established, however, duties attach, and the psychiatrist is liable for damages that are proximately caused by their breach (

Roberts v. Sankey 2004). Whether a psychiatrist-patient relationship exists is a mixed question of law and fact. If the existence of a relationship is disputed, the court determines, as a preliminary matter, whether the patient entrusted care to the psychiatrist and whether the psychiatrist indicated acceptance of that care (

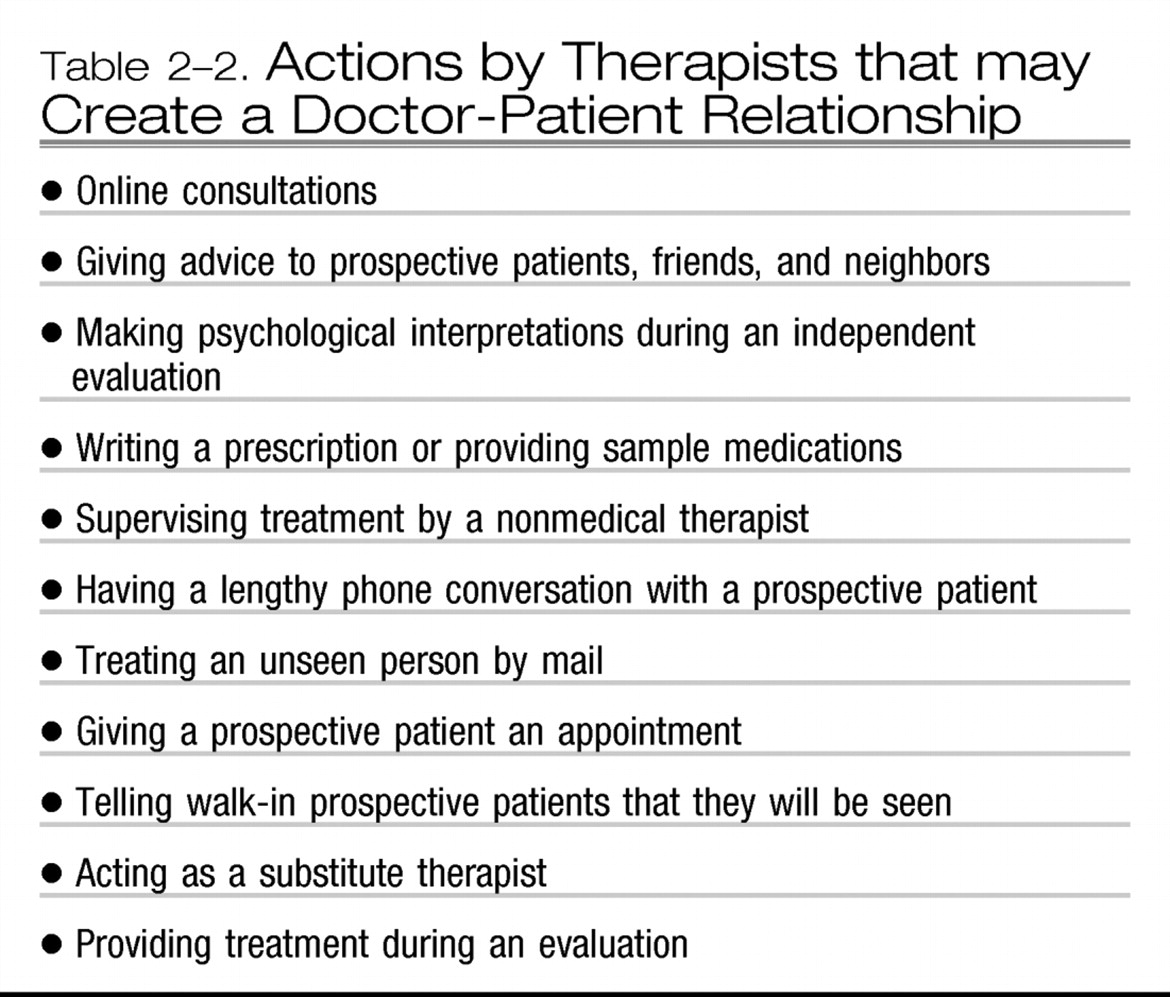

Dehn v. Edgecombe 2005). Most often, a psychiatrist-patient relationship is established knowingly and voluntarily by both parties. Occasionally, however, a doctor-patient relationship is unwittingly created.

Although the law imposes no duty on physicians to accept a prospective patient, courts have been quick to recognize a doctor-patient relationship when the physician affirmatively undertakes to diagnose and or treat a person (

Kelley v. Middle Tenn. Emergency Physicians, P.C. 2004). Several examples are instructive. Giving advice, making interpretations, or prescribing medication during the course of an independent medical evaluation may create a doctor-patient relationship (

Newman and Newman 1989). A doctor-patient relationship may be created when a person is provided care over the telephone, if that person has the expectation that he or she is accepted for treatment. Courts will likely treat doctor-patient relationships created by e-mail as they have those created by phone, mail, or in person (

Table 2–2).

Judicial decisions that hold therapists liable to third persons—not because they are patients, but because they allege that the therapist's negligent patient care resulted in harm to them—have increased. These claims have been made by persons about whom the patient made threats in therapy and who were later injured by the patient. The injured third party in these cases claims the threats were mishandled (

Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California 1976). Another class of third-party claims have been made by individuals who allege that, because of inappropriate therapies used by the psychiatrist, they were wrongfully remembered by the patient in therapy as having been the perpetrator of childhood sexual abuse (

Appelbaum et al. 1997). The duty issue in these cases is separate from the duty issue that arises with participants in formal family or group therapy. The courts addressing these third-party claims do not focus on the requirements for the existence of a doctor-patient relationship but instead on whether the harm that may have been caused by the therapist's negligence is proximate or too remote to be attributed to any negligence in the care of the patient.

Unless they are a formal part of the patient's therapy, families are usually not considered parties to the case (

Gutheil and Simon 1997). Family members who are brought into the patient's treatment in a brief, adjunctive role must be clearly informed that they are not being seen as patients. If therapy for other family members is indicated, they should be referred elsewhere for treatment.

Psychiatrists and other clinicians are often asked by friends, family members, neighbors, or colleagues for clinical advice or medications. These quasimedical relationships are potentially fraught with serious problems (

LaPuma and Priest 1992). Psychiatrists who wish to provide professional services in these situations must understand they may be creating a doctor-patient relationship with an attendant duty of care. As in the usual clinical situation, medical records should be maintained that document that the standard of care was met in evaluation, diagnosis, and indications for treatment.

Ordinarily, clinicians who perform preemployment, insurance, or workers' compensation examinations do so for the benefit of a third party, not the examinee, and accordingly a doctor-patient relationship does not arise for purposes of medical malpractice liability (

Chiasera v. Employers Mut. Liability Ins. Co. 1979;

Ervin v. American Guardian Life Assurance Co. 1988;

Violandri v. New York 1992). Independent of medical malpractice liability for negligence as a caregiver, psychiatrists may be liable for performing negligent examinations (

McKinney v. Bellevue Hosp. 1992) or for defamation if untrue and damaging statements are made about the examinee (

James v. Brown 1982). Therapists who examine litigants at the request of the court are typically immune from liability for negligence. Psychiatrists appointed by the court in civil commitment cases are generally protected from liability as well. When, however, the psychiatrist medically certifies his or her own patient, liability claims may not be barred by imposition of immunity for negligently initiated commitment. (This issue is examined further in Chapter 7, “Involuntary Hospitalization.”)

“Curbside consultations,” or informal advice given in response to a colleague's question, are not categorically excluded from the recognition of a duty of care enforceable in a medical malpractice claim because of their location, reimbursement, or informality. Rather, in the event of a malpractice claim, each consultation will be judged by the court on its own facts, applying the criteria generally applied for recognition of a doctor-patient relationship. Thus the law's expectations for consultations do not countenance a sliding competence scale for discounted opinions.

Patient evaluation: the right to accept or reject new patients.

When seeing a prospective patient for the first time, psychiatrists may want to conduct an evaluation before accepting the person as a patient. The clinician should inform the prospective patient that no treatment will be provided during the evaluation. In actual clinical practice, this may not always be possible. The psychiatrist usually does not know the extent of the prospective patient's disturbance prior to seeing him or her for the first time. Some individuals show floridly psychotic symptoms during the initial visit and may be a danger to themselves or others. The psychiatrist may decide to immediately intervene and forgo the initial evaluation period. The clinician's first duty is to the welfare of the patient.

The common law “no duty to rescue” rule is still very much good law. Not even health care professionals have a duty to come to the aid of a stranger who is helpless and in peril, but if that duty is undertaken there is an obligation to do so non-negligently (

Shuman 1993). The application of this rule to a psychiatrist in private practice means that he or she is not required to accept a new patient, but if he or she does there is an obligation to provide competent care. Psychiatrists may feel helpless and trapped when confronted with a new patient who is in a crisis and requires immediate attention. Psychiatrists who do not want to accept the patient for treatment should attempt to find immediate, competent help. In some instances, this may require accompanying the patient to a hospital or an emergency department. Professional ethics and concern for the patient in crisis dictate that the patient be assisted in obtaining immediate care (

Simon 1992).

Malpractice concerns can be an additional incentive to see prospective patients for an initial evaluation before accepting them for treatment. In split treatment or collaborative therapy, careful evaluation of the patient's suitability is necessary. Psychiatrists are increasingly vulnerable to lawsuits by patients seen within a short period of time, even less than 30 days. Eight out of every 10 persons who commit suicide have visited a physician within the 6 months prior to the attempt, and half (50%) have seen a physician within 1 month prior. The psychiatrist should perform a suicide risk assessment at the initial evaluation, even if the patient denies being suicidal.

Clinicians usually accept many more patients than they reject. Upon completion of the evaluation, a decision by both the psychiatrist and the patient can be made about whether to begin treatment. The psychiatrist should scrupulously avoid rendering advice, interpretations, or any other intervention that might be construed as treatment during the evaluation period.

Psychiatrists have no legal obligation to provide emergency medical care to a person who is not a patient (failure to provide emergency care to an existing patient may constitute abandonment). Nevertheless, the

American Medical Association (1989) advises, “The physician should, however, respond to the best of his [or her] ability in cases of emergency where first aid treatment is essential” (p. 33). If a psychiatrist undertakes to render assistance to the person “at the wayside,” Good Samaritan statutes provide a layer of protection for physicians providing gratuitous emergency medical care against damages arising out of any professional act or omission performed in “good faith” and not amounting to gross negligence (Estate of Heune ex. rel.

Heune v. Edgecomb 2005). Good Samaritan laws typically include the physician who is not licensed in the state where the emergency care takes place (for a listing of Good Samaritan statutes, see

Centner 2000).

Role conflicts.

The practice of psychiatry bristles with moral dilemmas. Role conflicts occur when mental health professionals have irreconcilable interests that interfere with their fiduciary responsibility to act solely in the best interest of the patient. These role conflicts are sometimes labeled as

double agentry, which refers to a conflict between serving the patient and serving some external agency (

The Hastings Center 1978). Role conflicts hold a high potential for interfering with the fiduciary duties psychiatrists owe their patients. For example, psychiatrists working in mental institutions must manage the conflict between serving their patients and advancing the goals of the institution and society. Following the emergence of

Tarasoff in those states that recognize a psychotherapist's duty to protect third parties endangered by their patients, psychiatrists were explicitly called upon to balance the conflicting duty to protect patient confidentiality and to protect persons identified as at risk in a patient's confidential communications. Psychiatrists who work in prisons, in schools, or in the military regularly face potentially serious double-agent conflicts. Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals are expected to clinically manage conflicting pressures that inevitably arise from these different sectors without disrupting the doctor-patient relationship.

Therapists who sexually exploit their patients violate their fiduciary responsibilities. Such violation also may occur when patients who have been sexually abused are referred to a new therapist for much-needed treatment, and the new therapist, because of forensic interests or moral outrage, converts the treatment relationship into a forensic case. The therapist may encourage the patient to file a lawsuit and help initiate ethical and licensure proceedings against the former therapist. Therapists should not confound treatment with advocacy. The roles of treater and expert witness must be kept separate to avoid serious conflicts of interest (

Strasburger et al. 1997). Advocacy should not be misrepresented to the patient as treatment. “Once a patient, always a patient” is a sound principle that allows patients to go about their lives free from the presence and influence of their therapists.

PATIENT BILLING

Dubious practices.

Conflicting, self-serving interventions can occur over billing and fees. Most therapists explain their fees at the beginning of treatment so that patients can agree, disagree, or enter into negotiations for a mutually agreed-on fee. Role conflicts can arise over billing for times reserved or by discounting or inflating bills.

Discounting of bills occurs when the patient has insurance but is unable to pay the full portion of the bill. The therapist may accept either no payment or a lower payment from the patient. When the psychiatrist accepts the insurance reimbursement as payment in full, the insurer is actually paying 100% of the bill. Insurance carriers consider this practice to be fraudulent because the participating psychiatrist is pocketing their “overpayment.”

Psychiatrists who inflate bills to insurance carriers may also be vulnerable to charges of fraud and misrepresentation. Inflating of bills refers to charging the insurance carrier a higher fee than the therapist is actually charging the patient. When this happens, the difference is pocketed or applied to the patient's portion. Therapists are not agents of the insurance company, nor should they be agents of the patient against the carrier. Exaggerating the severity of a patient's mental disorder to obtain coverage under managed care is a related deceptive practice. A position of neutrality on insurance matters maintains the psychiatrist's integrity and preserves the treatment. Engaging in dubious fee practices undermines the credibility of the psychiatrist if she or he becomes entangled with the patient in litigation.

Psychiatrists are entitled to charge a reasonable fee for their services. Billing for missed appointments is appropriate if the patient is advised of this practice at the outset and freely consents. Charges for missed sessions should not be represented as treatment sessions to third-party payers. This practice could be interpreted as misrepresentation and fraud. Psychiatrists who receive direct payment from third-party payers are not paid for appointments that are reported as missed. Moreover, under provider contractual agreements, most MCOs and other third-party payers prohibit psychiatrists from billing the patient for any unauthorized services, including missed appointments. The ethical and prudent course is to note missed appointments on the billing form, even if the psychiatrist must take a financial loss. In some circumstances, a legitimate arrangement may be worked out with the patient to pay for missed appointments.

Nonpayment: clinical issues.

In general, the psychiatrist has no legal duty to continue to treat patients who do not pay. The psychiatrist, however, must be careful not to abandon the patient. The patient who runs out of money during the course of extended therapy presents a difficult problem. Terminating the patient's treatment may be very destructive to the unique relationship that developed between psychiatrist and patient. The psychiatrist may decide to treat the patient for a token fee until the patient's financial situation improves, at which time a new fee can be negotiated. Allowing the patient to pay the money owed at a later date places the psychiatrist in the position of a creditor, a potentially conflicting role. Similarly, entering into a barter arrangement with a nonpaying patient should be avoided. Patients in need of treatment may not be able to objectively assess the value of their goods. When others assume financial responsibility for the patient, the therapist may wish to formalize the arrangement with a written agreement. As insurance benefits for psychiatric care continue to be cut back by MCOs and other third-party payers' cost-containment policies, treatment of patients needing further care may be improperly terminated.

ABANDONMENT

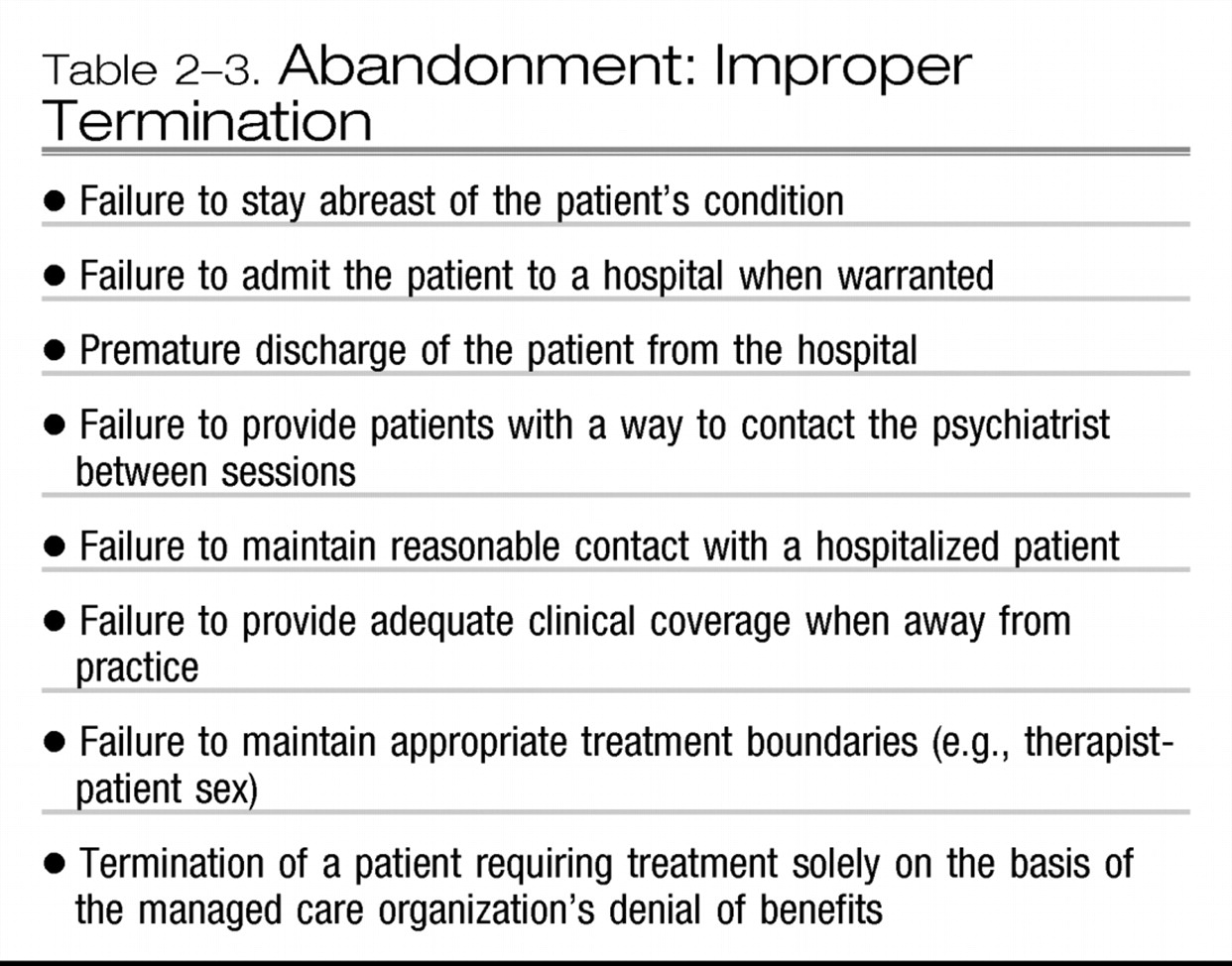

Once the psychiatrist agrees to treat the patient, a psychiatrist-patient relationship is formed with the duty to provide treatment as long as is necessary. When the psychiatrist-patient relationship is unilaterally and prematurely terminated by the psychiatrist without reasonable notice, the psychiatrist may be liable for abandonment if care is still needed by the patient (see

Grant v. Douglas Women's Clinic P.C. 2003). If an emergency exists, the psychiatrist should see the patient through the current crisis or make suitable arrangements for attendance of another qualified mental health professional (see

Johnson v. Vaughn 1963). For patients in perpetual crisis, this is a daunting task. Similarly, terminating treatment of a chronically ill patient who is in serious psychiatric difficulty should be deferred until the immediate crisis is over or until the patient is well enough to be transferred or discharged.

Although the doctor-patient relationship may be terminated unilaterally by the patient, the following actions by a patient do not, in and of themselves, terminate the doctor-patient relationship:

•.

Nonpayment of a bill (However, there

are limits: for example, in Surgical Consultants,

P.C. v. Ball [1989], the court ruled that the doctor did not have to continue treatment when the patient failed to pay her bill after 11 sessions.)

•.

Noncooperation in treatment (However, the physician does not have to continue treatment when there is no hope of helping the patient through current therapy.)

•.

Unilateral consultation with another mental health professional

•.

Failure to keep an appointment

None of these actions by the patient, in and of themselves, constitutes unilateral termination of treatment. However, these issues should be taken up as treatment matters. If the patient stops coming for regularly scheduled appointments, does the therapist have a duty to contact the patient? The answer to this question depends on whether the patient's absence is a direct function of mental illness. The more severe the illness, the more the psychiatrist should assume responsibility for contacting the patient. When it is not clear whether the patient has terminated treatment, the psychiatrist should attempt to clarify the patient's intentions concerning further treatment. If a patient stops coming for treatment without further explanation, the psychiatrist should send a certified letter (return receipt requested) to ascertain whether treatment has been terminated by the patient.

When the doctor-patient relationship has not been properly terminated by the patient, by the psychiatrist, or by the mutual agreement of both, the negligent acts may be categorized as abandonment of the patient (see

Table 2–3).

Psychiatrists who request other psychiatrists to hospitalize their patients should stay in contact with the admitting psychiatrist and shift temporarily into a consultative role. Unless the patient is being permanently transferred to the care of the hospitalizing psychiatrist, the referring psychiatrist should continue to stay abreast of clinical developments with his or her patient. Communication between psychiatrists is essential to the patient's care.

Finally, abandonment may become an issue when therapists do not list a phone number in the telephone directory or with directory assistance. Being inaccessible to patients measurably increases their anxiety and causes some patients to go to extraordinary lengths to find their therapists. Ready availability of the psychiatrist appears to diminish patients' anxiety and results in fewer calls. In addition, if an emergency should arise, claims of abandonment are preempted when the psychiatrist can be easily contacted. Leaving a message on the answering service such as “If you have a true emergency, please go to your nearest emergency department” may be perceived by the patient as abandonment. In an emergency, patients want to speak to their psychiatrists. Waiting for hours to be seen in an emergency department may exacerbate the patient's illness and result in the patient leaving prematurely.

TERMINATION

The psychiatrist has the right to terminate a doctor-patient relationship if proper notice is given so that the patient may find a suitable substitute (see

Brandt v. Grubin 1974).

Unilateral terminations.

A psychiatrist may seek to terminate a patient's treatment because of managed care limitations on insurance benefits. However, the liability exposure for terminating treatment of a patient in crisis because of managed care restrictions is high. As noted earlier, termination of treatment for the patient in crisis should be deferred until his or her situation is reasonably stabilized. Before termination, the psychiatrist should give the patient sufficient notice to make other treatment arrangements. The psychiatrist should also review with the patient the current diagnosis, the importance of continuing with prescribed treatments, and the need for additional treatment. A note in the patient's chart and a brief letter sent to the patient should summarize the psychiatrist's treatment recommendations. The psychiatrist may decide to continue to treat a patient after managed care benefits end. Managed care contracts should be checked for any clause that prohibits treatment of managed care patients under a private fee-for-service arrangement.

The patient has the right to leave treatment at any time and without notice. In some instances, the patient may terminate by simply not showing up for scheduled appointments. A patient who is mentally ill and poses a substantial danger to self or others may suddenly decide to terminate. In such instances, the psychiatrist's ethical and professional duties to care for the patient continue and require that the psychiatrist consider a variety of clinical interventions.

Some patients are genuinely difficult and demanding in their own right, presenting unique problems that some psychiatrists can handle better than others. The fit between psychiatrist and patient may not be workable. If treatment becomes stalemated or contentious, the patient should be referred elsewhere.

Professional and ethical duty demands that the psychiatrist not treat patients beyond the point of benefit. Patients can become mired in therapeutic stalemates extending for years. This situation tends to occur when an Axis I clinical syndrome is successfully treated, but the remaining Axis II personality disorder goes undiagnosed or is intractable to treatment. Even though the patient may strenuously resist, it is not abandonment if such a patient is referred to another therapist who may be able to treat the patient more effectively once the previous treatment is appropriately terminated.

Method of termination.

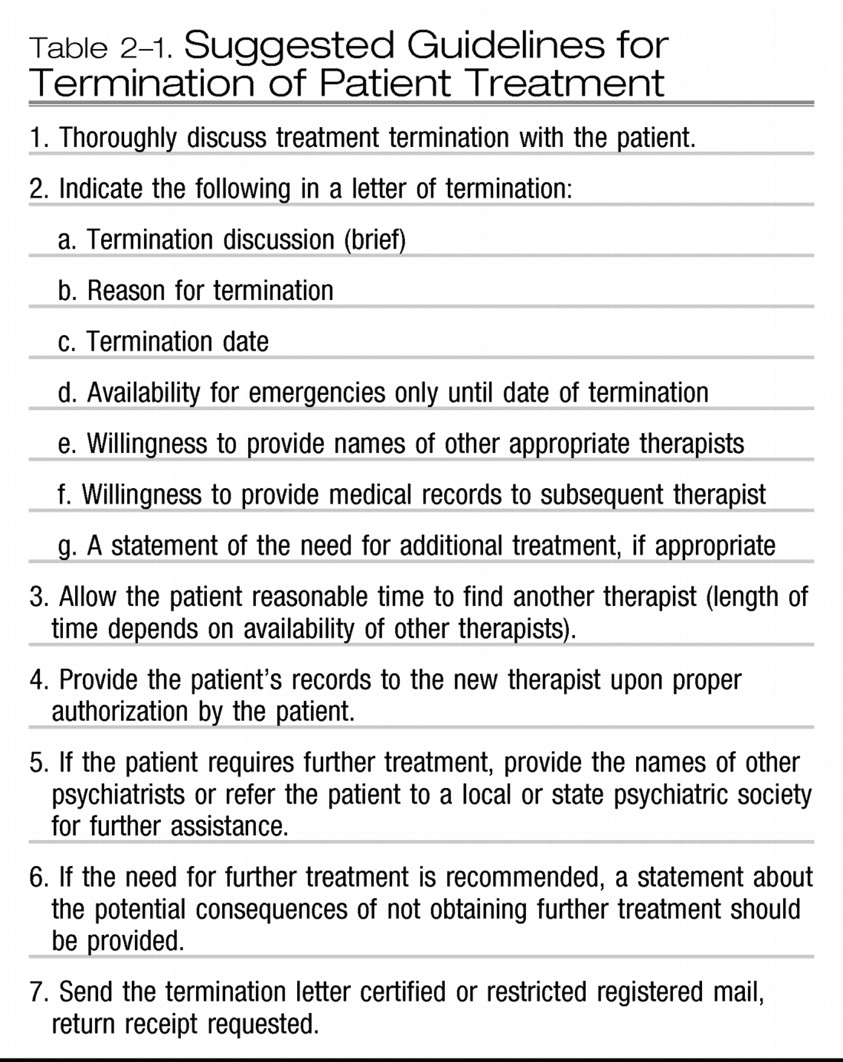

Termination and the treatment issues surrounding it should be openly discussed with the patient and a notation of the discussion placed in the patient's record. A certified letter notifying the patient of termination should be sent and a return receipt requested. If the terminated patient is seen again after the letter is issued and termination is still intended, the entire termination process must be reinstituted (

Table 2–1).

How much time should the patient be given to find another therapist? The time allowed should be based on the severity of the patient's condition and the availability of alternative care. Patients who present with complex, severe mental illnesses may find it more difficult to find a psychiatrist willing or able to treat them. Sufficient notice also depends on the locality. The availability of psychiatrists in rural settings is often limited. The patient may need more time to find a psychiatrist than would be necessary in an urban area. The courts have used such normative words as ample, sufficient, and reasonable when referring to the time that should be given the patient to find a substitute.