Psychosomatic-medicine psychiatrists often see patients on medical wards who lack the capacity to make treatment decisions when their refusal of necessary treatment may put their health at risk. (

1) Although civil commitment because of mental illness and/or being dangerous has been a statutorily regulated and well-studied practice in general psychiatry, (

2) there is currently a dearth of information about the issue of involuntary hospitalization for medical patients seen in consultation-liaison psychiatry whose medical disorders may either transiently or more chronically affect their mental status, leading to psychosis, confusional states, and impaired judgment.

Consultation-liaison psychiatrists often struggle with problems presented by patients who lack decisional capacity secondary to a medical illness, are not verbally threatening to self or others, and want to leave the hospital against medical advice (

3). Such patients at times have personality changes secondary to a general medical condition or delirium secondary to a general medical condition, (

4) but in particular jurisdictions may not meet the criteria or be appropriate for commitment to a psychiatric facility. Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are often consulted on such cases where the patient repeatedly attempts to leave against medical advice and may be combative and require restraints (

3). This was precisely the dilemma captured in the following case of “Ms. S.” In this report, specific information about the case has been modified in order to deidentify the details of the case, yet the clinical factors remain illustrative of the difficulties that consultation-liaison psychiatrists often encounter.

CASE REPORT

Ms. S was a 46-year-old woman with multiple medical problems, including HIV/AIDS, HIV dementia, non-insulin-dependent diabetes, history of basilar tip aneurysm, status post-coiling of aneurysm, and an extensive past psychiatric history including bipolar disorder, polysubstance dependence, and multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. She presented to the emergency department with a severe headache and was admitted to the neurosurgery service for assessment and evaluation. During the hospital course, she underwent neurosurgical evaluation and work-up that revealed a questionable new hemorrhagic lesion. On Hospital Day 2, the Psychiatry Consult service was called to evaluate symptoms of paranoia. The impression of the consult team was that she had cognitive disorder, not otherwise specified, or HIV-related dementia. The psychiatric team continued to follow the patient, who subsequently developed a fever and became increasingly confused. Upon further assessment, the consult team believed that she did not have decisional capacity related to her medical treatment. The clinical opinion was based on the observations by the psychiatrists that Ms. S lacked decision-making capacity related to her inability to appreciate her clinical situation and its consequences and her inability to manipulate information presented about her treatment. Specifically, she stated that discontinuing her HIV medications or leaving the hospital against medical advice would not put her health at risk. She was unable to rationally discuss the information about her treatment as she vehemently discussed the futility of treatment even when presented with information about its potential benefits. The consult team's impression was that the lack of capacity was related to a diagnosis of delirium. The cause of delirium was thought to be infectious, yet the exact infectious etiology was not known at that time. The consult team suggested that the medical team pursue guardianship. Pharmacological management of the delirium was also recommended and prescribed at that time.

On Hospital Day 5, before a guardian was instituted, the Psychiatry Consult service was called again because the patient was agitated, combative, and attempting to leave the hospital against medical advice. Consistent with the previous assessment, the on-call psychiatric consultant determined that she lacked capacity to make medical decisions and fit the diagnosis of delirium secondary to a general medical condition, in the context of an underlying HIV dementia. Her delirium work-up was ongoing, and the etiology of her delirium was still not known. Because Ms. S refused to cooperate with a formal cognitive examination, the diagnosis of delirium was based on her waxing and waning mental status, disorientation, memory impairment, and clouding of consciousness. She alternated between extremes of agitation and somnolence. She repeatedly fell asleep while speaking. Furthermore, her presentation differed markedly from her previous psychiatric presentations, providing additional support for the diagnosis of delirium.

The patient was considered dangerous to herself secondary to her lack of decision-making capacity in light of her progressively worsening medical condition. Through-out, she had been hospitalized on a voluntary basis. Her request to leave led to much confusion among hospital staff, given her status as a voluntarily hospitalized patient. The impression of the psychiatrist on call was that Ms. S did not meet criteria for psychiatric commitment, nor was it clinically indicated. Under Massachusetts General Laws, application for an involuntary admission to an inpatient psychiatric facility is specified with the following limitations: “Symptoms caused solely by alcohol or drug intake, organic brain damage, or mental retardation do not constitute a serious mental illness” (

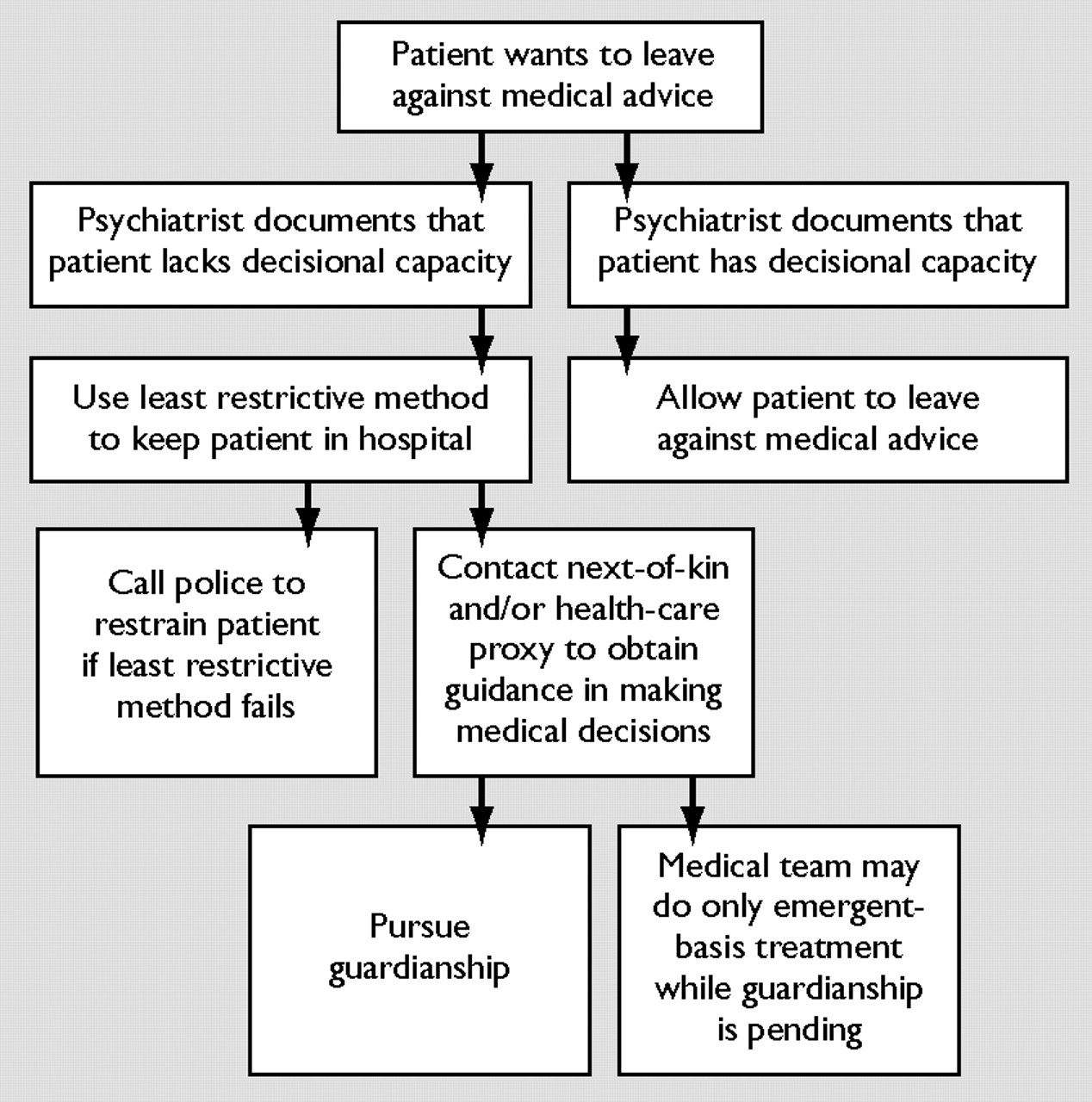

6). The clinical consult team felt that, in light of the language of the statute, Ms. S's diagnosis of delirium secondary to a general medical condition qualified as “organic brain damage” and therefore precluded her from meeting criteria for civil commitment under the jurisdiction at issue. Even if she had met clinical criteria for pursuing involuntary commitment, Ms. S had acute medical issues that made transfer to a psychiatric unit not an appropriate option at the time. The psychiatrist on call recommended that Ms. S should not be allowed to leave against medical advice and that the medical team should use restraints to keep her in the hospital if less restrictive methods failed.

The treating physicians were not able to redirect Ms. S, and she remained combative and continued to demand to leave against medical advice. At that time, it was decided that Ms. S needed to be restrained in order to maintain her safety. The campus police refused to restrain the patient, stating that she could not be restrained or kept in the hospital against her will without psychiatric legal commitment documents. The psychiatrist on call discussed this refusal with the hospital police sergeant, who also reported that the patient could not be restrained or kept in the hospital against her will without psychiatric legal commitment documents. The medical team and psychiatrist on call had reached an impasse with the police. The patient needed to be restrained to maintain her safety; the police adamantly refused to restrain her without commitment documents; and the patient did not appear to the clinical team to meet commitment criteria.

The medical team, the psychiatrist on call, and the police debated this point while Ms. S became increasingly agitated. While the medical team was trying to come to an agreement as to how to manage Ms. S, she voiced suicidal ideation. In view of her recently reported suicidal thoughts, psychiatric commitment documents were completed and placed in the chart. The rationale for completing commitment documents at that time was based on her newly-stated suicidal thoughts. According to the consulting psychiatric team, she now fit commitment criteria based on “substantial risk of harm to self as manifested by threats of or attempts at suicidality” (

6). Although the consulting psychiatrist was aware that her suicidality may have been part of her delirium presentation, the patient was clearly at risk. Completing commitment papers seemed the only way to maintain the patient's safety, and the consulting psychiatrist did what was necessary. Attributing her suicidality to affective symptoms in the context of a patient with an underlying mood disorder appeared to the consulting team to be an appropriate clinical rationale used to complete the application for her commitment. This also allowed additional time to assess the patient's evolving presentation and the need to proceed to a judicial commitment hearing. Once commitment documents were completed, the police restrained the patient, and she was able to be kept on the medical floor.

This case was particularly frustrating to those involved because the treating physicians and hospital campus police had differing opinions about how this patient should be managed. Eventually, psychiatric commitment documents were completed; yet neither the treating physicians nor the police were certain whether this was the appropriate step. There was a lack of understanding among all involved as to how Ms. S should be kept in the hospital, both legally and ethically. Ms. S's delirium resolved after several weeks, yet she did not regain decisional capacity, and it was determined that she had an underlying severe HIV dementia that continued to impair her decisional capacity. Guardianship was pursued and obtained before her discharge to the community. The hospital attorney was alerted to the case and the confusion that had ensued related to the requirements for involuntarily holding a patient on a medical floor. Training seminars for campus police and a consultation-liaison seminar presentation were subsequently initiated in order maximize multidisciplinary understanding of “restraints” laws and policies.