INTRODUCTION

In Hong Kong in 1997 an employer elected not to hire two healthy job applicants because they had reported a family history of mental illness (

1). In the USA, beginning in 2000, an employer gathered genetic data from employees, without explicit consent, regarding supposed susceptibility to carpal tunnel syndrome in an effort to avoid financial culpability for disability claims from injured workers (

2,

3). Both actions were identified in the courts of these countries as discriminatory, and both occurred in the past decade. Legislation to protect nearly 3 million federal workers in the USA was passed in 2000 (

4). As this paper was being written in 2005, the US Senate passed a landmark bill to prohibit discrimination on the basis of genetic information with respect to health insurance and employment for more than 130 million US workers (

5). This bill, if endorsed by the US House of Representatives and signed by the President, would prohibit discrimination toward employees or job applicants in hiring, firing, compensation, conditions or terms of employment on the basis of genetic information. It would ensure key safeguards regarding confidentiality of genetic information, and it specifies that genetic information could be used

only to help protect employees from exposure risks in the workplace.

With the achievement of the sequencing of the full genome of humans and other species, and with extraordinary recent scientific developments related to the application of genetic information, many unprecedented ethical and legal issues of great importance to our global society have emerged. Some of these concerns relate to practical considerations such as confidentiality protections and informed consent procedures, and yet others relate to more abstract, and more profound, issues such as the nature of being human, free will, justice, privacy and the ethical use of power in society (

6).

The conceptual and empirical literatures in ‘genethics’ have lagged considerably behind the dramatic scientific effort witnessed over the past decade (

7–

10). In the specific area of employment-related genetics ethics issues, only a handful of academic articles have been published. Interestingly, the popular media have given more attention to this topic. More encouraging are the numbers of resource and policy documents that have been developed by leading government and scientific organizations in Europe and the USA, which have collaborated in the Human Genome Project and which will be the focus of this review. This body of work, taken together, will serve as the basis of this review, which will focus on three key interrelated ethical and policy concerns: (1) genetic testing and the use of genetic information in the workplace; (2) the dual role of occupational physicians related to genetics in the workplace; and (3) genetic research in the workplace.

GENETIC TESTING AND USE OF GENETIC INFORMATION IN THE WORKPLACE

Genetic testing in various forms has been used in the workplace since the 1970s (

11**). In recent years, genetic tests have targeted genetic variants that contribute to susceptibility to illness, such as berylliosis in workers who undergo exposure to beryllium, and genetic polymorphisms of detoxification enzymes that may be partial determinants of cancer risk (

12,

13).

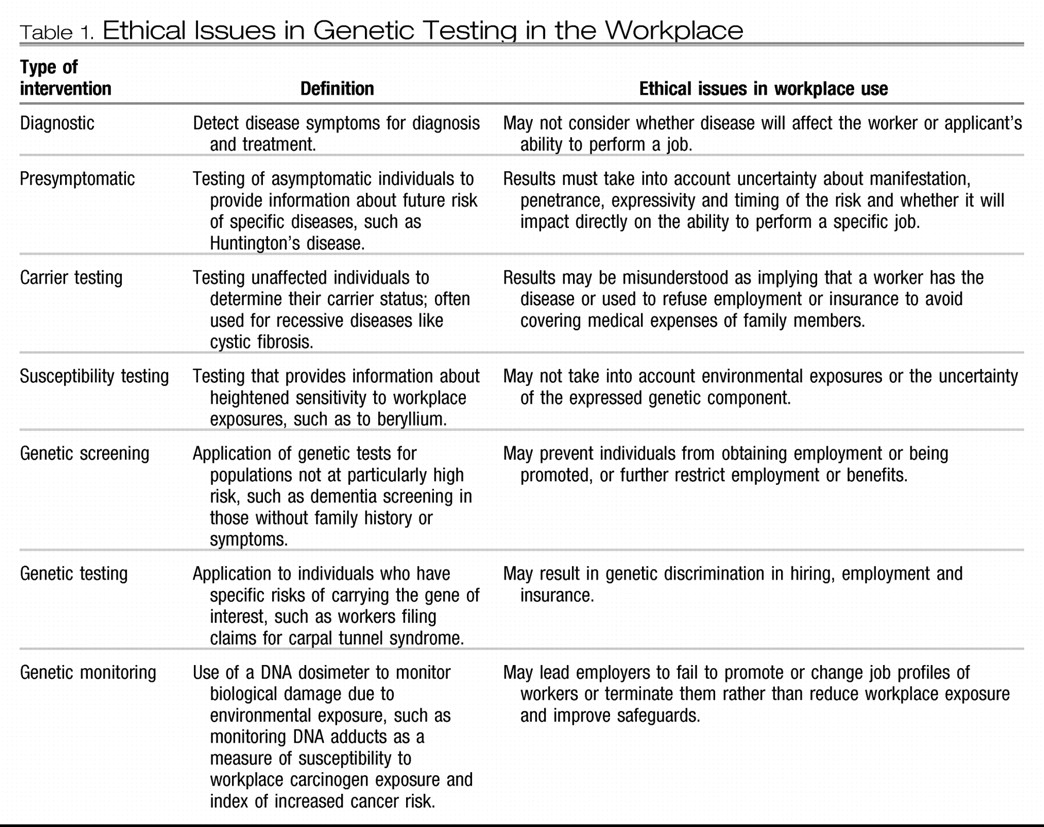

Table 1 lists the definitions of the various types of genetic tests relevant to workplace genetics, as outlined by the Human Genome Advisory Commission (

14).

A widely publicized case of genetic testing involving Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad in 2001 raised public and professional awareness of the possibility of genetic discrimination associated with genetic susceptibility testing (

2,

3). The company had requested employees to submit a blood sample which they used to detect a genetic variation on chromosome 17 that indicated a susceptibility to developing carpal tunnel syndrome. The employees were not aware of the purpose of the test. The US Equal Opportunity Commission filed a suit challenging that this use of workplace genetic testing violated the Americans with Disabilities Act. In response to the suit, the company agreed to stop requiring genetic testing of those employees who filed claims for carpal tunnel syndrome.

This case is often cited in policy statements as a harbinger of potential discrimination that may occur in the wake of the Human Genome Project (

11**,

15). Most experts agree that while occupational genetic testing and screening is not currently widespread, the application of new technologies such as DNA microarrays will quickly lead to the development and utilization of genetic tests for many common polygenic disorders with relevance in the workplace, such as asthma, cancer and depression (

16–

18). There is concern first that these tests will be used before their reliability, validity, sensitivity, specificity and predictive value are established and second that both patients and providers - who often lack education in medical genetics - will misinterpret the complexity of genetic information resulting in adverse consequences.

VIEWS OF GENETIC TESTING IN THE WORKPLACE

Little is known about the extent of genetic testing that presently occurs in occupational settings as well as the degree of genetic discrimination that may exist. The majority of the few studies exploring the prevalence were performed 10–20 years ago (

19–

23).

Recent empirical work suggests that testing, and certainly discriminatory practices, may not in fact be common, but that insurers, employers and workers can envision positive uses for genetic data. In a study of genetic information used by 200 insurers, Hall and Rich (

24,

25) found that there were few well-documented cases of insurers using presymptomatic genetic test results in underwriting decisions. A study in 2000 carried out by the Institute of Directors in the UK found that only two out of 353 directors reported using genetic tests routinely. Nevertheless, 34% approved of using genetic screening with employee consent for the detection of heart disease and 8% thought that screening should be mandatory if it was in the employee's best interest. Fifty percent approved of genetic testing with employee consent to determine development of occupationally related disease due to workplace exposure and 26% thought such testing should be mandatory (

26). In a small but unique study, Roberts and colleagues (

27*) surveyed 63 employed persons in two US work settings (a health sciences center and a scientific laboratory) regarding their attitudes toward the use and protection of genetic information. Workers expressed a strong interest in learning about their personal genetic information. They wished to control access to their personal genetic data, and they saw genetic information as more sensitive, and in greater need of protection, than general health information. The respondents identified a number of negative psychosocial consequences of disclosure of risk of genetic illness, including significant concerns about workplace use of genetic information.

In media-based polls, the public has expressed substantial fears that genetic information will be used detrimentally in society. A 2000 Time/CNN poll found that 46% anticipated harmful results from the Human Genome Project while only 40% expected benefits. Only 20% thought genetic information should be available to insurance companies, while 14% thought the government should have access (

17). A 2001 study conducted in Britain found that seven out of 10 people think it is inappropriate for an employer to see the results of an applicant or employee's genetic test and that 0% think it is appropriate for an employer to have access to test results that indicate where the worker is a risk to colleagues or the public (

28). Respondents did feel it was appropriate for employers to view information that discloses susceptibility to hazardous substances that may be encountered on the job. A 2001 American Management Survey found that only two firms reported currently performing genetics testing, while 14% were conducting susceptibility testing (

29). However, several scholars have posited that the limiting factor on the application of genetic technology in the workplace is not moral compunction but rather economics and efficacy and that once tests become more affordable and efficient they will be utilized much more generally (

24,

25). There is concern that legal and regulatory protections will not be able to keep abreast of the pace of commercial biotechnology, leaving many workers vulnerable to the adverse ramifications of genetic testing (

30).

In summary, genetic information in the workplace has often been characterized as a two-edged sword. It carries the potential to reduce worker disability, improve employee health, lower economic costs and improve productivity, but it also represents a threat to employee autonomy and privacy, and may result in loss of life and health insurance, employment or promotion, and in genetic discrimination and stigmatization (

31–

33).

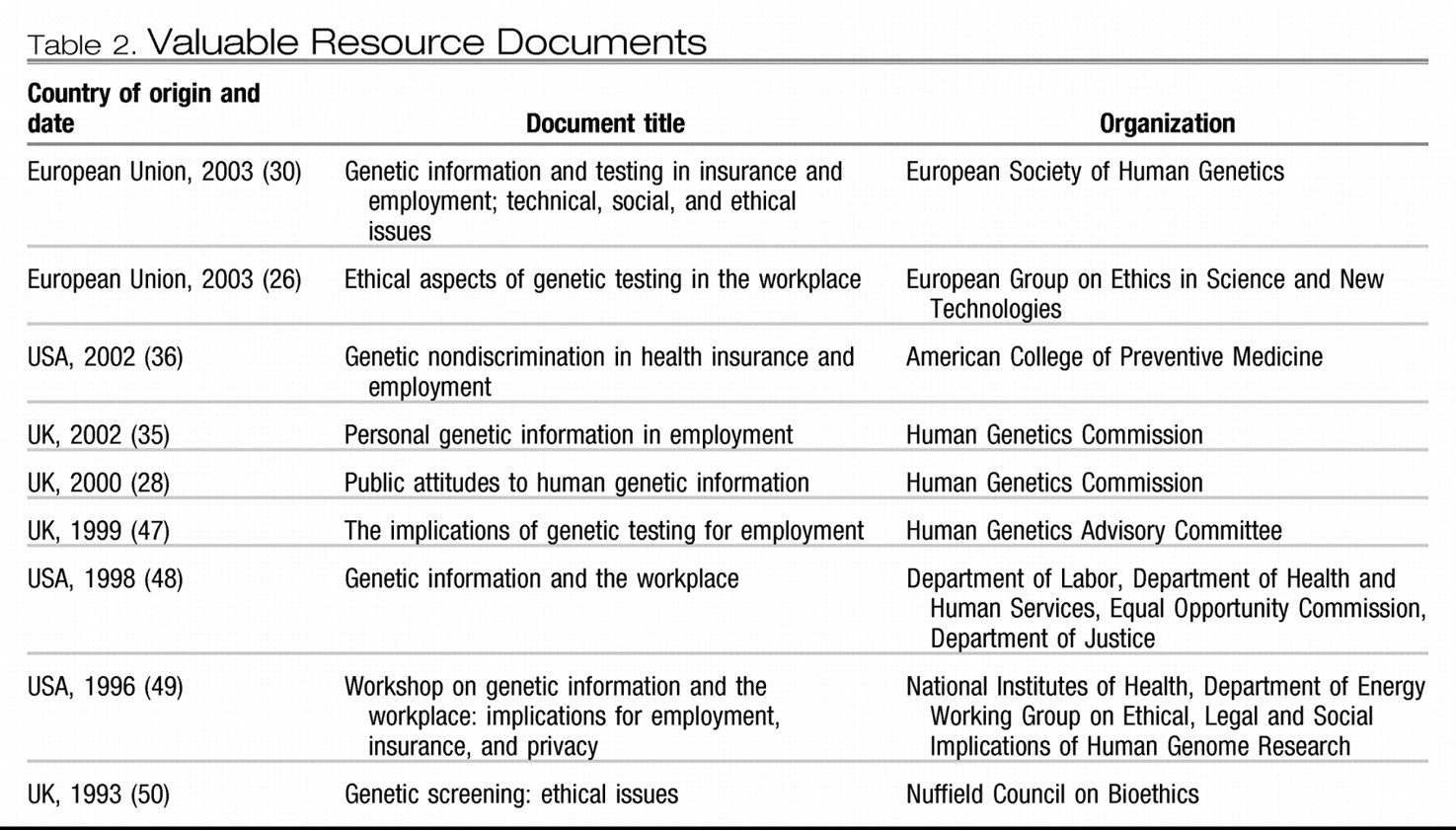

RESOURCE DOCUMENTS AND EMERGING STANDARDS

Recently, several professional organizations and government agencies in Europe and the USA have issued policy statements on the ethical safeguards required for genetic testing in the workplace (see

Table 2). The European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies prepared a thorough resource document on ethical considerations in genetic testing, encompassing workplace applications, and including a valuable summary of findings from reports and legislation in many countries (

26). The key concepts articulated in this document are that: (1) genetic tests must balance the autonomy of the worker against the duties of employers to provide protection for employees, the worker tested and third parties; (2) health-and-safety benefits of tests must outweigh the harms of intrusion on privacy and potential discrimination; (3) workers to be tested must provide informed consent and receive pre- and post-test counseling with careful attention to the power differential between employee and employer, which may result in subtle coercion of applicants or workers to be tested; (4) employers must protect both their own workforce and any third parties that could be injured as the result of illness - in some cases, testing may be the only way this duty can be fulfilled but the use of such tests must meet strict criteria including document validity, informed consent, confidentiality protections and release of information to an independent health professional rather than the employer; (5) results with limited predictive value have little import on an employee's current ability to perform her job and hence should not be utilized particularly to make determinations about future fitness for duty; (6) few tests to date have demonstrated the validity, relevance, reliability and predictive value that would warrant making hiring, employment or promotion decisions on the basis of results and are outweighed by the harm stemming from false-negative and -positive results, such as anxiety, loss of insurance and job termination.

Several prestigious institutions have underscored that the autonomy of workers and the ethical accountability of employers must be the guiding principles of occupational genetic testing. The Wellcome Trust, in its valuable opinion statement (

34), points out that genetic testing, primarily through screening methods, should not replace employers' primary responsibility to ensure a safe workplace and to eliminate hazardous exposure, even for those who may be genetically susceptible. Only when environmental control of the substance is not possible should genetic monitoring be warranted, and then only with employee consent. The Human Genetics Commission of the UK supported previous recommendations that employers could not demand genetic tests as a condition of employment and that, in those cases where testing might be warranted, employers, unions and other stakeholders should refer these cases to the commission so the ethical implications can be assessed (

35). Similarly, the European Society for Genetics (

30) has recommended that in cases in which genetic testing is indicated, a new regulatory model should govern their administration in which an independent agency supervises the voluntary testing rather than the employer, and the testing is targeted at specific agency-identified workplace hazards and the results be given directly only to the employee.

In 2002 the American College of Preventive Medicine (

36) issued policy recommendations regarding genetic non-discrimination in employment. The college banned discrimination in hiring, compensation and other personnel processes, prohibiting employers from requiring or requesting employees' disclosure of predictive genetic information and requiring that employers treat such information as confidential. It allows information pertaining to monitoring to be used only to assess the hazardous effects of workplace exposures. The policy further states that genetic information must be disclosed to the employee on request and released only to authorized researchers. The American Association of Occupational Health Nurses (

37) affirms these provisions and also recommends that proper mechanisms for redressing inappropriate use of genetic information, including right to legal action, be instituted.

There is increasing interest in developing guidelines such as these as expected standards within the global community, and many of these guidelines may be evaluated for their impact and effectiveness and for ‘benchmarking’ decisions in real settings (

38). For instance, it has been suggested that quantitative techniques may be used to assess the advantages and disadvantages of preplacement screening for employees, which would permit certain judgments to be based on empirical evidence rather than simple value judgments being made (

38,

39). Data could be developed regarding factors such as the proposed number of applicants to be screened in order to prevent a single adverse outcome, the number of applicants excluded to prevent one case with an adverse outcome, the expected incidence of adverse outcomes in those excluded and the overall preventable fraction of cases. Such efforts involving sophisticated mathematical models and individual and epidemiological data, it is argued, could inform ethical decisions with personal health, legal, economic and societal effects, and could be used to bring greater sophistication to the discussion of genetics ethics issues in the workplace and alternative preventive measures that may be undertaken.

DUAL ROLE OF OCCUPATIONAL PHYSICIANS

The advent of genetic testing, information use and research will not so much raise novel ethical dilemmas in occupational medicine as expand and complicate the fundamental tension between the occupational physician's obligation to promote the economic interests of employers and duty to protect the health of the worker. Emanuel (

40) and other authors have emphasized that traditional bioethics rooted in the physician-patient relationship provide little guidance for occupational physicians facing institutional dilemmas and organizational conflicts of interest (

41,

42). The new emphasis on worker productivity in occupational health exemplifies the types of ethical problem that will accompany the application of genetic technology to the workplace. Because employers generally provide or subsidize health insurance, they have the financial incentive to prevent disease leading to absenteeism, disability or workers' compensation in employees and, further, to maximize employee health, which is tied increasingly to worker productivity and hence company profit.

Recent articles on the economic cost of depression and its related impact on worker productivity illustrate the movement, and the exponential rise in health-care costs will only accentuate this trend. Brandt-Rauf and Brandt-Rauf (

11**) and others (

43) have underscored how genetic knowledge will enable employers to expand their ability to detect inherited or acquired genetic risks for disease and disability with corresponding possibilities to compromise privacy, employment and insurability. Occupational physicians will be the gatekeepers and brokers of this knowledge and will require new ethical direction to maneuver conflicts of interest and confidentiality dilemmas (

11**,

43). With this direction it will be recognized that economic interests also bear ethical weight given finite resources and the need for their fair distribution, and that the health of the community of workers and the society at large are also considerations that must be factored into the traditional formulation of an occupational physician's moral duties (

40).

GENETIC RESEARCH IN THE WORKPLACE

Two empirical studies have been performed to examine the views of workers regarding genetic research. Wong et al. (

44) conducted a community-based study in Singapore with 548 individuals, 49% of whom would be willing to give a blood sample for genetic research. Willingness was associated strongly with positive beliefs about the benefits of genetic studies and with a lack of fear of pain, blood, injections and needles and non-concern about confidentiality issues (

44). This study echoes the findings of Roberts et al. (

45*) who surveyed 63 employees in two settings and then analyzed a subset of items that assessed attitudes toward ethically relevant issues related to participation in genetic research. These workers strongly endorsed the importance of physical and mental illness genetic research, and they expressed favorable views of the inclusion of 12 special population groups, such as children, elders, pregnant women, individuals in the military and persons with mental illness. They perceived more positives than negatives in genetic-research participation, giving neutral responses regarding potential risks. They affirmed many motivations for participation to varying degrees. Interestingly, men tended to affirm the importance of, acceptability of and motivations for participation in genetic research more strongly than women.

Genetic environmental health researchers are keenly aware of the ethical, legal and social problems involved in occupational genetic research. Unless these problems are addressed, access to employee research participants and data pertaining to environmental exposures may be restricted. Christiani and colleagues (

18) proffered three recommendations to guide environmental genomics. First, environmental scientists should be actively engaged in policy debates concerning the ethical implications of their research through participation in professional organizations and national policy discussions. Second, researchers should follow the precedent of the Human Genome Project and support ethical, legal and social research parallel to their own basic and epidemiological investigations. Third, a major focus of environmental geneticists should be the education of future research subjects and institutional review-board members regarding the ethical and legal issues involved in this type of study, with particular emphasis on obtaining informed consent and conveying research results to participants as well as anticipating and preventing racial or ethnic discrimination associated with particular genetic variations.

A contemporary subject of discussion in the occupational research literature is whether and under what conditions subjects should have access to interim findings. White (

39) summarized both sides of the question and argued that respect for participant autonomy and informed consent justify providing interim findings with the provisions that investigator and participants jointly determine the circumstances of disclosure. She contends that the assessment of clinical value must be derived from the participant, which will promote trust between volunteers and researchers (

39), while others (

46) have contended that investigators are best suited to making this assessment because of the complex, incomplete and uncertain nature of the results.