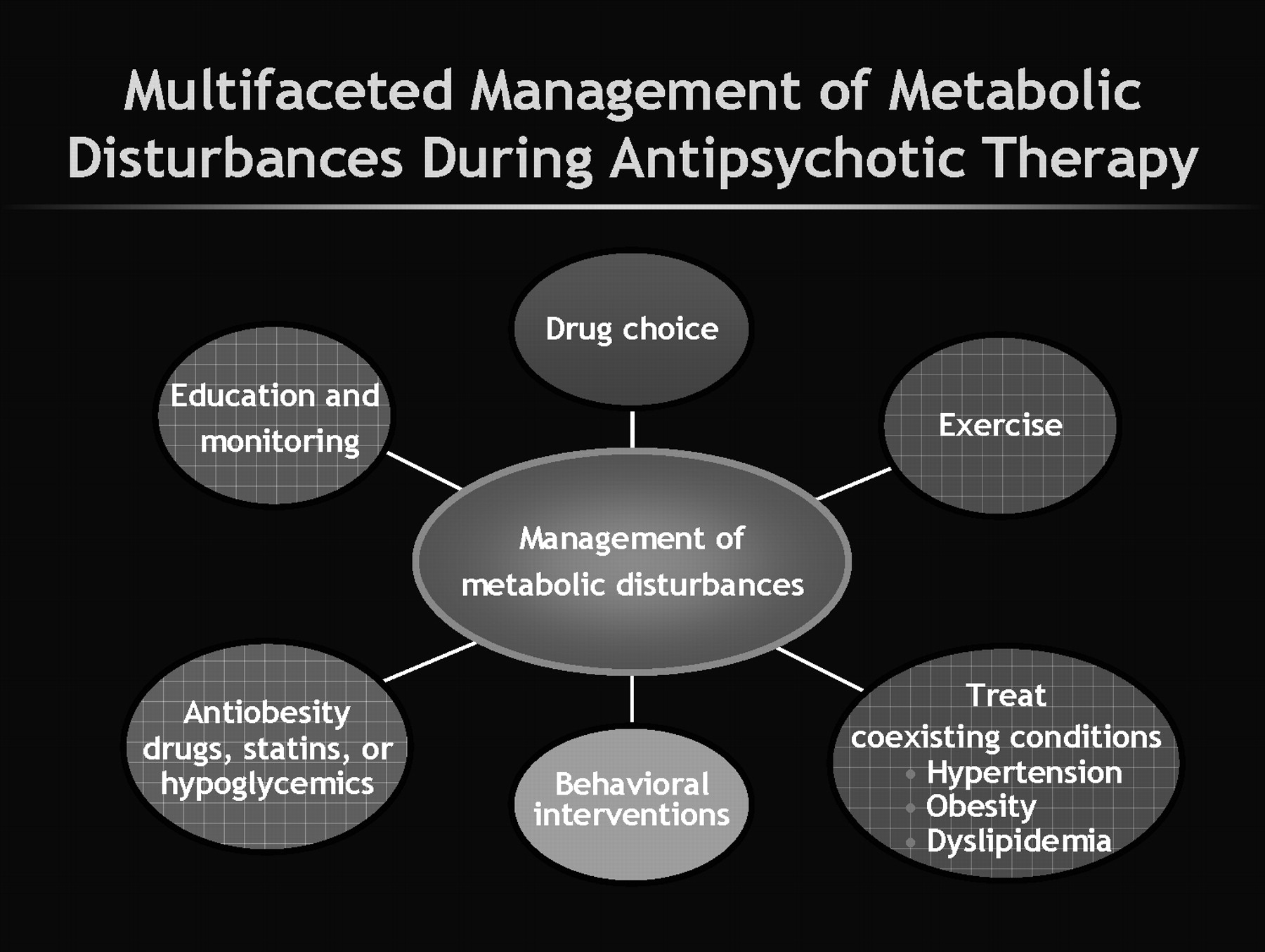

There are several up-front clinical implications. To effectively manage this problem a multifaceted approach is required (

Figure 2). First, it is now incumbent upon clinicians to measure weight and metabolic parameters before starting antipsychotic treatment and also to reassess these regularly during treatment. This need emerges “loud and clear” from several guidelines (

49–

51). However, clinicians are slow to change practice habits and at least when looked at during 2001–2003, there was a low level of measuring for MS in practice (

52,

53). It is likely, especially given the medicolegal specter now surrounding this topic, that the situation has changed. How best to implement widespread change in our clinical practice is also unclear (

54). Henderson et al. (

55) have shown that regular monitoring of hemoglobin A1C can aid in detection of diabetes during antipsychotic therapy.

Second, we need to encourage patients to improve their nutrition and to use available weight loss programs. There is evidence that these strategies work (

56). Brar et al. (

57) reported that 26.5% of patients receiving a (simple) behavior intervention lost 5% or more weight. This was in comparison with weight loss seen in 10.8% of patients in regular treatment when evaluated over a duration of 14 weeks. A recent Chinese 12-week study (

58) tested a behavioral modification strategy and an antiobesity drug (metformin) in first-episode schizophrenia patients who had already gained weight from their antipsychotic therapy. Patients who got standard therapy alone (i.e., no intervention for weight gain) gained more weight, whereas significant reductions in weight and in measures of insulin functioning were seen in the other three groups, i.e., those who received some intervention, either pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, or combined medication and behavioral treatments. The best results were seen in those patients who received both metformin and the lifestyle intervention.

Third, we need to develop more comprehensive and better integrated medical models for the long-term care of patients with serious mental illness (

59). Collaborations with nursing and with primary care physicians offer advantages here (

60,

61). Currently, medical management for patients with serious mental illness is below par (

62–

64). For example, in CATIE there was less than expected prescription of medications to address the extent of diabetes and hypertension that was reported in patients (

62).

In terms of medication management, switching antipsychotics is probably the best option at present. Weiden (

65) provided a review of this strategy and cited several studies showing benefits such as reduction in weight and metabolic disturbances when patients switch antipsychotics. It is also important to complete the switch as incomplete switches result in polypharmacy, which itself may be associated with a greater risk for diabetes (

66). Another problem with the switching strategy is that it is unclear for any individual patient what benefit or risk the patient will actually incur until the switch is made (

67). Additionally, current switch studies provide limited guidance as these studies are open labeled. A federally funded switch study, Comparing Antipsychotics for Metabolic Problems (CAMP), is currently underway (

36). There are also a variety of add-on strategies that have been tried to reduce weight and metabolic disturbance. Recently, DeHert et al. (

68) reported benefit from adding the lipid-lowering agent rosuvastatin in patients with schizophrenia. There is also interest in considering rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 antagonist, which has been shown to be beneficial in obese, nonpsychiatric patients (

69). However, this agent is still investigational, and it also seems to have increased incidence of psychiatric side effects. The use of a histamine-1 blocker has shown some benefit in patients with schizophrenia (

70). Topiramate has also been used (

71). There was even interest in considering fluoxetine as an add-on to help with weight gain during olanzapine therapy (

72). It should be noted, however, that even in nonpsychiatric obese populations, the evidence that these agents are helpful is mixed at best (738). Moreover, the evidence for real benefit in patients with schizophrenia is even more sparse.