Depression is perhaps the most frequent cause of emotional suffering in later life and significantly decreases quality of life in older adults (

2–

7). In recent years, the literature on late-life depression has exploded. Excellent North American epidemiological studies from the 1980s and early 1990s have been complemented by more recent reports from other countries (

2,

4,

8–

12). Many gaps in our understanding of the outcome of late-life depression have been filled (

13–

15). Intriguing findings have emerged regarding the etiology of late-onset depression (

16–

18). The number of studies documenting the evidence base for therapy has increased dramatically (

19,

20). In this review, I first address case definition, and then I review the current community- and clinic-based epidemiological studies. Next I address the outcome of late-life depression, including morbidity and mortality studies. Then I present the extant evidence regarding the etiology of depression in late life from a biopsychosocial perspective (

6,

21). Finally, I present evidence for the current therapies prescribed for depressed elders, ranging from medications to group therapy. Given the plethora of literature, important (though on my view not critical) studies have necessarily been omitted, yet the current review reflects the astounding advance of our database since I reviewed the subject in 1989 (

22).

CASE DEFINITION

Clinicians and clinical investigators do not agree as to what constitutes clinically significant depression, regardless of age, nor is there universal agreement about how depression should be disaggregated into its component subtypes. The subtypes most cogent to late-life depression are reviewed in the paragraphs that follow. (Because of space limitations, bereavement and bipolar disorder have been omitted from this review.) There is considerable overlap across these subtypes, as the differentiations often reflect particular orientations toward dissecting the syndrome, that is, different ways of “slicing the pie.” When the factor structure for the range of depressive symptoms is examined across the life cycle, there are no major differences between Caucasians and African Americans (

23), between men and women (

4,

23), or between older and younger adults (

4,

24).

Major depression is diagnosed in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), when the older adult exhibits one or both of two core symptoms (depressed mood and lack of interest) along with four or more of the following symptoms for at least 2 weeks: feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt; diminished ability to concentrate or make decisions; fatigue; psychomotor agitation or retardation; insomnia or hypersomnia; significant decrease or increase in weight or appetite; and recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation (

25). The symptoms of moderate to severe depression presented to the clinician are similar across older adults and persons in midlife if there are no comorbid conditions (

26). However, there may be subtle differences by age. For example, melancholia (symptoms of noninteractiveness and psychomotor retardation or agitation) appears to have a later age of onset than nonmelancholic depression in clinical populations, with psychomotor disturbances being more distinct in older persons (

27,

28).

Minor, subsyndromal, or subthreshold depression is diagnosed according to the Appendix of DSM-IV when one of the core symptoms just listed is present along with one to three additional symptoms (

25). Other operational definitions of these less severe variants of depression include a score of 16+ on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (

29) but not meeting criteria for major depression (

10), a primarily biogenic depression not meeting criteria for major depression yet responding to antidepressant medication (

30), or a score of 11–15 on the CES-D (

31) and therefore not meeting the CES-D criteria for clinically significant depression, that is, subthreshold depression. Minor depression variously defined has been associated with impairment similar to that of major depression, including impaired physical functioning, disability days, poorer self-rated health, use of psychotropic medications, perceived low social support, female gender, and being unmarried (

10,

31).

Other investigators have suggested a syndrome of

depression without sadness, thought to be more common in older adults (

32,

33), or a depletion syndrome manifested by withdrawal, apathy, and lack of vigor (

34–

36).

Dysthymic disorder is a long-lasting chronic disturbance of mood, less severe than major depression, that lasts for 2 years or longer (

25). It rarely begins in late life but may persist from midlife into late life (

37,

38). The aforementioned list is actually truncated from all the different potential subtypes of depression that have been suggested, both past and present. Modern psychiatry has been criticized for its tendency to split syndromes into so many different subtypes without adequate empirical (especially biological) data to justify such splitting (

39). One investigator has suggested that the only meaningful split of the depressive spectrum is a split between the more physical symptoms of depression (such as anhedonia, agitation, and perhaps some of the symptoms of executive dysfunction, see the paragraphs that follow) and the more psychological symptoms (

40).

Depression in late life is frequently

comorbid with other physical and psychiatric conditions, especially in the oldest old (

41). For example, depression is common in older patients recovering from myocardial infarction and other heart conditions (

41,

42), and in those suffering from diabetes (

43), hip fracture (

44), and stroke (

45). In community-dwelling Mexican American elders, depression was associated with diabetes, arthritis, urinary incontinence, bowel incontinence, kidney disease, and ulcers (a profile different from Caucasians, who exhibit comorbidities such as hip fracture and stroke) (

46). Major depression is generally thought to be present in approximately 20% of Alzheimer's patients (

47–

49). In some studies, however, the rates are much lower (1–5%) (

50). Depressive symptoms may be common even in elders with mild dementia of the Alzheimer's type (

51).

Some differences have been reported between

early onset (first episode before the age of 60) and

late onset (first episode after the age of 60) depression. Personality abnormalities, a family history of psychiatric illness, and dysfunctional past marital relationships were significantly more common in early onset depression (

52). However, when severity, phenomenology, history of previous episode, and neuropsychological performance were compared, there were no differences between early onset and late onset depression in elderly people (

52).

Interest in differentiating early- versus late-onset depression in late life has arisen in large part because some people have speculated that contributors to etiology may vary by age of onset. For example,

vascular depression (depression proposed to be due to vascular lesions in the brain) may be much more common with late-onset depression, and the clinical presentation may differ, even if only in subtle ways (

16,

47,

53). Severely depressed older adults exhibit impairment in set shifting, verbal fluency, psychomotor speed, recognition memory, and planning (executive cognitive function) (

54). The clinical presentation of elderly patients with this “depression-executive dysfunction syndrome” is characterized by psychomotor retardation and reduced interest in activities but a less pronounced vegetative syndrome than is seen in the depressed without executive dysfunction. The dysfunction consists of impaired verbal fluency, impaired visual naming, and poor performance on tasks of initiation and perseveration (

55,

56). Vascular depression is associated with absence of psychotic features, less likelihood of a family history, more anhedonia, and greater functional disability when compared with nonvascular depression (

16,

47,

53,

57).

Psychotic depression, when contrasted with nonpsychotic depression, occurs in 20–45% of hospitalized elderly depressed patients (

58) and 3.6% of persons in the community with depression (

59). Recently a group of investigators proposed a

depression of Alzheimer's disease. In persons who meet criteria for dementia of the Alzheimer's type (

25), three of a series of symptoms that includes depressed mood, anhedonia, social isolation, poor appetite, poor sleep, psychomotor changes, irritability, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, and suicidal thoughts must be present for the diagnosis to be made (

60).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF LATE-LIFE DEPRESSION

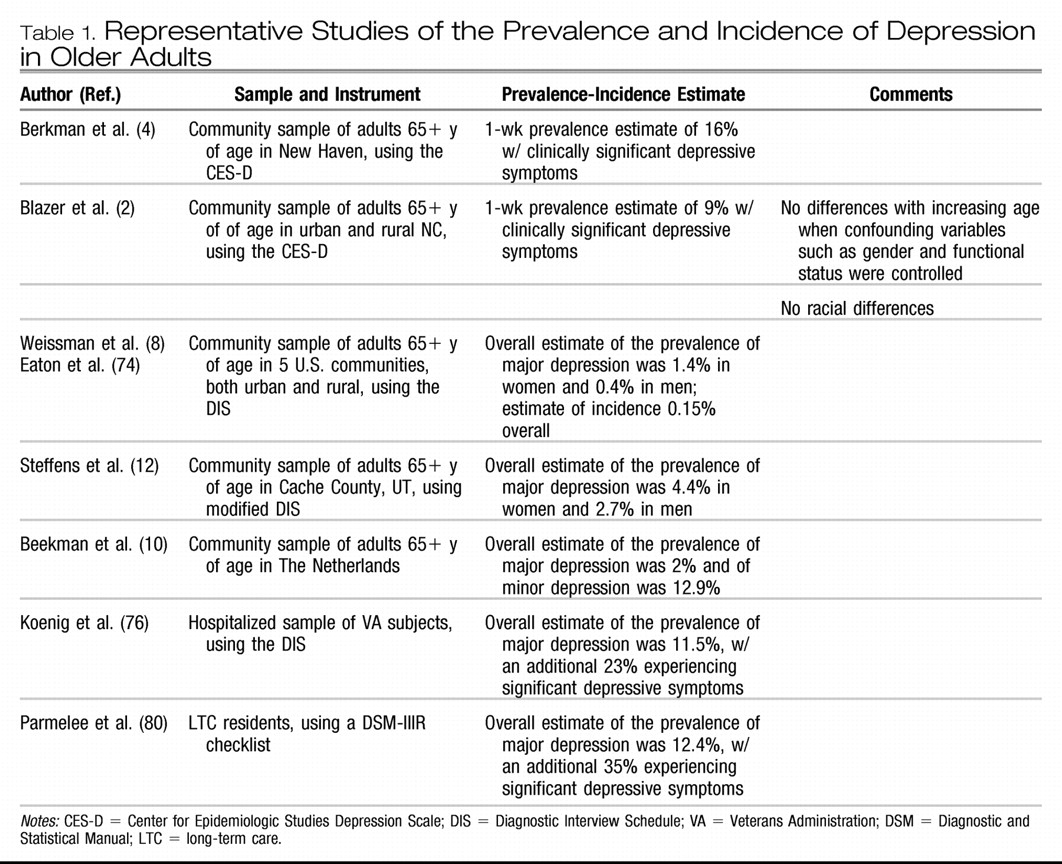

Depressive symptoms are less frequent (or no more frequent) in late life than in midlife (

2,

61,

62), though some suggest these estimates are biased secondary to “censoring” of population studies of older adults by means of increased mortality among the depressed and difficulty in case finding (

63) (see

Table 1). In a recent study, the lower frequency of depressive symptoms in elderly people compared with people in midlife was associated with fewer economic hardships and fewer experiences of negative interpersonal exchanges among both older disabled and nondisabled respondents. In addition, religiosity among older disabled adults also accounted for part of the lower frequency (

64).

Reports of the prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults range from approximately 8% to 16% (

2,

4,

9,

62,

65). Some suggest that depression may be more frequent among Mexican Americans than among non-Hispanic Caucasians and African Americans. In one study, 25% of older Mexican Americans scored 16+ on the CES-D (

66). In studies of samples of mixed Caucasians and African Americans, rates are similar (

2,

4). Nevertheless, African Americans are generally seen by psychiatrists to have fewer depressive symptoms and are much less likely to be treated with antidepressant medications (

67,

68).

Depressive symptoms are more frequent among the oldest old, but the higher frequency is explained by factors associated with aging, such as a higher proportion of women, more physical disability, more cognitive impairment, and lower socioeconomic status (

41,

69). When these factors are controlled, there is no relationship between depressive symptoms and age (

2). The 1-year incidence of clinically significant depressive symptoms is high in the oldest old, reaching 13% in those aged 85 years or older (

70).

The prevalence estimates of major depression in community samples of elderly people have been quite low, ranging from 1% to 4% overall, with higher prevalence among women yet with no significant racial or ethnic differences (

3,

9,

11,

12). Estimates for dysthymia and minor depression are somewhat higher, with the same pattern of distribution across sex and race or ethnicity. In the North Carolina Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study, in which the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) was used (

71), the prevalence estimate was 0.8% for major depression, 2% for dysthymia, and 4% for minor depression (

3). Prevalence in the ECA studies overall in the elderly population was 1.4% in women and 0.4% in men (

8). The prevalence of major depression in the Cache County, Utah, study of community-dwelling elderly persons was 4.4% in women and 2.7% in men (

12). In Liverpool, investigators estimated 2.9% of elders with major depression and 8.3% with minor depression (

72). In The Netherlands, investigators found 2.0% of older persons with major depression and 12.9% with minor depression (

10). In Sweden, prevalence of major depression in the community was higher among the oldest old, from 5.6% at the age of 70 to 13% at the age of 85 (

73).

In the United States, the estimate of incidence (new cases over a year) of major depression from the ECA overall was 3 per 1000, with a peak in subjects in their fifties (

74). The incidence of major depression in elderly people was 0.15%, similar to the rate in younger age groups (

70,

74,

75). In a study from Sweden, the incidence of major depression was 12 per 1000 person-years in men and 30 per 1000 person-years in women between the ages of 70 and 85. The incidence increased from 17 per 1000 person-years between the ages of 70 and 79 to 44 per 1000 person-years between 79 and 85.

The prevalence estimates for major depression among older adults hospitalized for medical and surgical services is 10–12%, with an additional 23% experiencing significant depressive symptoms (

76). Major depression affects 5–10% of older adults who visit a primary care provider (

77–

79). For example, in one study among 247 subjects in a primary care setting, 9% were diagnosed with major depression, 6% with minor depression, and 10% with subsnydromal depression. Fifty-seven percent of these depressed patients experienced active depression at 1-year follow-up (

77).

In one large study of a long-term care (LTC) facilility, 12.4% experienced major depression and 35% experienced significant depressive symptoms (

80). In another study, depression was found in 20% of patients admitted to a LTC facility. Incidence of major depression at 1 year was 6.4% (

81). In another study of an LTC facility, prevalence of major depressive disorder among testable subjects was 14.4% (15% could not be tested) and prevalence of minor depression was 17%. Less than 50% of cases were recognized by nursing and social work staff (

82). Recognition and treatment in LTC facilities for depression is consistently poor across studies. For example, only 55% of depressed patients in one LTC facility received antidepressant therapy, and 32% of those received inadequate doses (

83). Screening LTC patients for depression, such as by using the Geriatric Depression Scale (

84), can increase the frequency of treatment or referral by primary care physicians in LTC (

85).

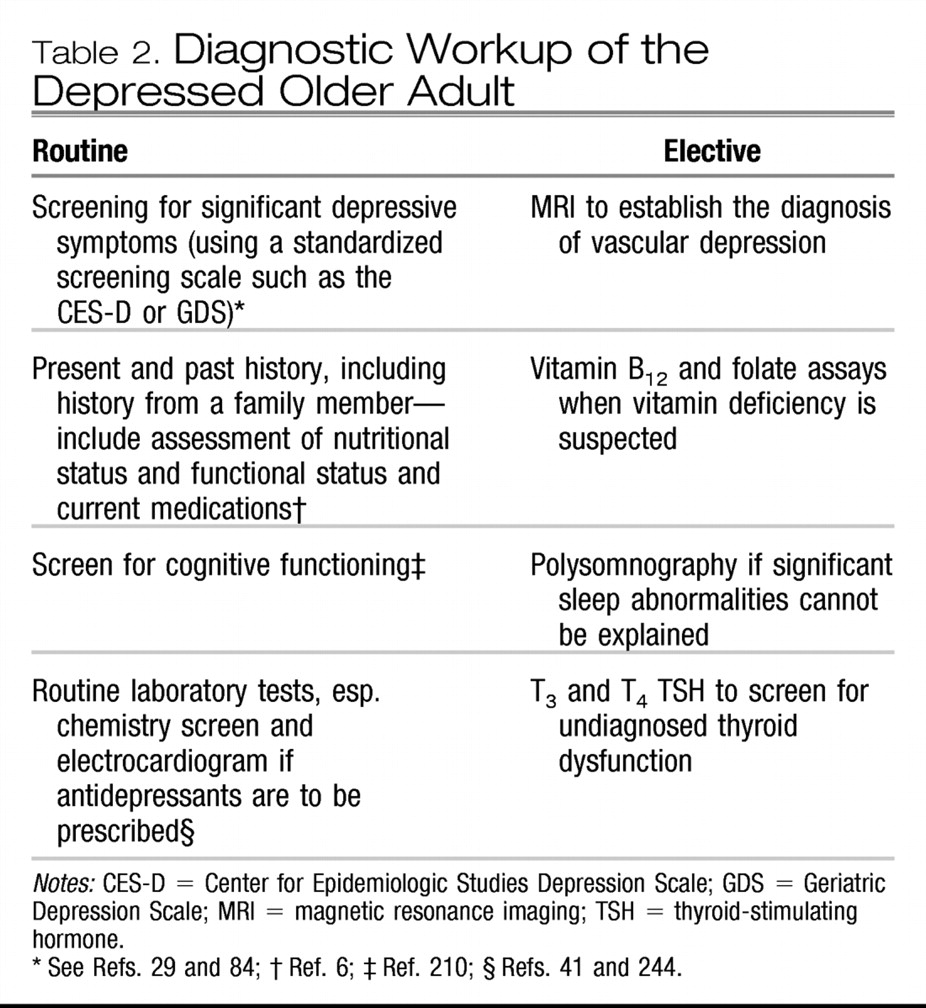

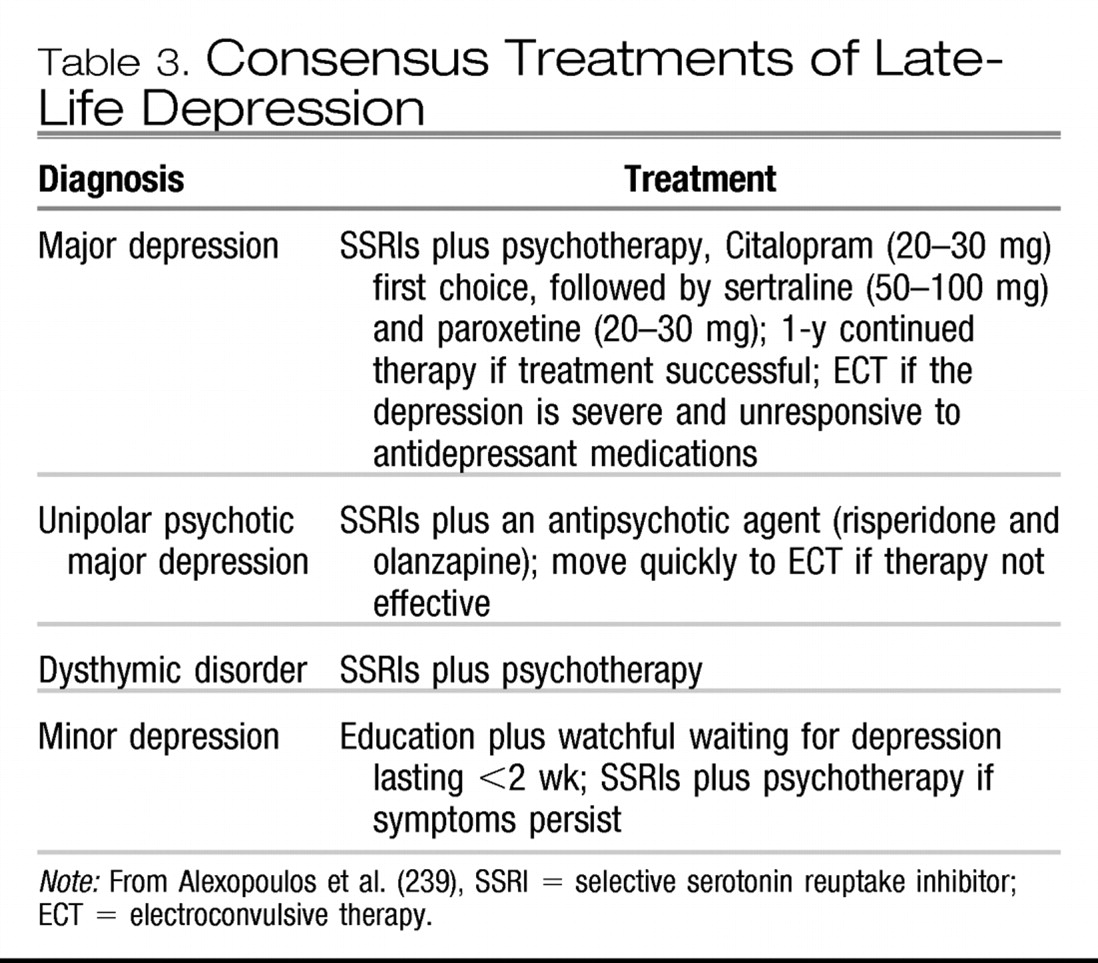

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Much of the diagnostic workup of late-life depression derives from what we know about symptom presentation and etiology (see

Table 2). Basically, the diagnosis is made on the basis of a history augmented with a physical and fine-tuned by laboratory studies. There is no biological marker or test that makes the diagnosis, though for some subtypes of depression, such as vascular depression, the presence of subcortical white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging scanning are critical to the diagnosis (

6,

185).

Screening is beneficial when standardized screening scales such as the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) or the CES-D are used (

29,

84,

205). Screening in primary care is critical. Not only is the frequency of depression high, but suicidal ideation is high as well. The prevalence of serious suicidal ideation in one primary care setting was 1% and the prevalence approaches 5% among older adults who report significant symptoms of depression (

206,

207). However, the documented success of screening has been mixed in extant studies. Internists tend to accept responsibility for treating late-life depression but perceive their clinical skills as inadequate and are frustrated with their practice environment (

207). Nearly all studies of treatment efficacy with pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy focus on older adults with uncomplicated major depression, which may apply to less than 15% of the depressed people in primary care (

208). Primary care physicians were informed of patient-specific treatment recommendations for depressed patients 60+ years of age in one controlled study. The patients of physicians in the intervention group were more likely to be diagnosed with depression and prescribed antidepressant medications, though the outcome of the depression was no better for the intervention group than for the control group (

209).

Cognitive status should be assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), given the high likelihood of comorbid depression and cognitive dysfunction (

210). Nutritional status is most important to evaluate in the depressed elder, including height, weight, history of recent weight loss, lab tests for hypoalbuminemia, and cholesterol, given the risk for frailty and failure to thrive in depressed elders, especially the oldest old (

41,

106). General health perceptions (

211) as well as functional status (activities of daily living) should be assessed for all depressed elderly patients (

212,

213). Other factors critical to assess in the diagnostic workup include social functioning (

214), medications (many prescribed drugs can precipitate symptoms of depression), mobility and balance, sitting and standing blood pressure, blood screen, urinalysis, chemical screen (e.g., electrolytes, which may signal dehydration) and an electrocardiogram if cardiac disease is present (especially if antidepressant medications are indicated) (

41).

CAN LATE-LIFE DEPRESSION BE PREVENTED?

The extant psychiatric literature suggests virtually no empirical evidence of psychosocial primary prevention. A MEDLINE review of the

American Journal of Psychiatry from 1990 to 2001 and the

American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry from 1997 to 2001 did not yield a single empirical study of the primary prevention of depression in the elderly population (or of an intervention strategy that might be considered universal) (

291). The few references to primary prevention of late-life depression focused on blood pressure control to prevent cerebrovascular disease as a means of preventing vascular depression (

292). In contrast, these journals are replete with articles regarding secondary prevention, that is, the early treatment of depression with medications and psychotherapy to remit depression and prevent its serious consequences as already described (

19,

272). As already described regarding the PROSPECT study, tertiary prevention (prevention of the serious consequences of late-life depression such as suicide) has received attention as well. The biological emphasis of today's psychiatry coupled with the paucity of empirical studies that document the benefit of primary (or universal) prevention undoubtedly have influenced recent contributions to the literature.

A recent study among elderly people is directly relevant to primary prevention (

293). Elderly subjects who experienced chronic illness were randomly assigned to a classroom intervention, a home study program, and a wait list. Both interventions provided instruction on mind-body relationships, relaxation training, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, communication, behavioral treatment for insomnia, nutrition, and exercise (a multimodal intervention strategy that integrates many approaches to enhancing self-efficacy in elderly people). The home version was delivered by class videotapes and readings. Compared with the control condition, both interventions led to significant decreases in self-reports of pain, sleep difficulties, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Such nonpharmacological interventions among vulnerable older adults may become increasingly important in our efforts to decrease the burden of depression among older adults.