CRAFTING A TREATMENT PLAN

We use a collaborative, patient-centered approach when developing a treatment plan for older adults living with comorbid depression and chronic pain. Severity of depression and type of pain (localized versus widespread or diffuse pain) are two of the primary variables that guide treatment planning. Patients with mild depression and localized pain (e.g., knee OA) often have improvements in mood, pain, and functioning with attention to behavioral medicine recommendations (such as diet and exercise), which have effects on both 1) improving self-efficacy (

77) and 2) reducing disability (

78). For example, assistance with weight loss and encouragement to exercise (

79,

80), delivered in a supportive/behavioral intervention such as problem-solving therapy (

81,

82), has been shown to be efficacious in improving mood and disability. In our psychiatric practice, we routinely refer patients to and collaborate with colleagues in physical therapy. Physical therapy often improves depression (

83). Our primary care colleagues appreciate the attention that we pay to the psychological, analgesic, and physical health of their patients.

Analgesics can improve the mild depression associated with pain and disability. Probably the mechanism of action of analgesics is not as conventional antidepressants (i.e., via the traditional monoamine hypothesis), but rather by improving mobility and independence, decreasing pain, and improving sleep. For two excellent reviews of the treatment of older adults with chronic pain, readers are referred to a report by the American Geriatrics Society, “The Management of Chronic Pain in Older Persons” (

18), and an article by Weiner, “Office Management of Chronic Pain in the Elderly” (

84).

Patients with depression and widespread pain often require an approach different from that for those with depression and localized pain. The most common cause of diffuse widespread pain in older adults is fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS). As with other types of musculoskeletal pain, FMS increases in prevalence with age and affects 7% of women aged 60 to 79 (

85). The criteria used for FMS include a history of generalized body pain (i.e., pain in at least 3 of 4 body quadrants) for at least 3 months duration and at least 11 of 18 specific tender points on physical examination (

86). Even if patients do not have at least 11 tender points, but the clinical picture suggests FMS (i.e., in addition to pain, patients report stiffness, fatigue, headache, cognitive impairment, poor sleep, irregular gastrointestinal and urinary functioning, depression, and anxiety), we generally apply either the diagnosis of FMS or the DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of “Pain Disorder Associated with Both Psychological Factors and a General Medical Condition” and initiate treatment.

Despite an increase in research on FMS, its pathogenesis is not fully understood. Recent data indicate that patients with FMS have enhanced sensitivity to multiple types of sensory stimuli (

87). Most experts agree that central sensitization plays a key role in FMS symptoms. Central sensitization suggests a heightened response of the central nervous system to nonpainful stimuli (allodynia) and painful stimuli (hyperalgesia). It is common for multiple central sensitization syndromes including FMS, headache, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and restless leg syndrome to present as comorbid conditions. Depression is comorbid with FMS in up to 34.8% of patients (

16) and frequently presents with these other central sensitization conditions. Thus, these conditions may be viewed as an affective/pain central sensitization syndrome. This makes sense, as 1) there is overlap in the brain regions implicated in these conditions and 2) the treatments for these conditions are often the same (e.g., antidepressants and cognitive behavior therapy).

When less common causes of widespread pain in older adults are ruled out (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, or polymyalgia rheumatica) and patients are also depressed, treatment with both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition is indicated. In a study comparing 20 mg/day fluoxetine and 20 mg/day amitriptyline with placebo in a randomized, double-blind, crossover study, Goldenberg et al. (

88) reported that patients receiving both fluoxetine and amitriptyline had improvement in pain, global well-being, and sleep disturbance scores. The combination of fluoxetine and amitriptyline was more effective than either alone. We do not recommend the routine use of either of these medications for older adults because of the long half-life of fluoxetine and the anticholinergic and cardiac effects of amitriptyline. Another double-blind placebo-controlled study using citalopram for FMS showed no improvement in pain scores or global functioning with the active agent (

89). Milnacipran is a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, available only in Europe and Asia, that reduces pain and fatigue and improves overall well-being in patients with FMS (

90). Esreboxetine, a highly selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is currently being evaluated as a treatment for FMS. Given its noradrenergic properties, it will probably have antidepressant and antianxiety properties as well.

Currently, the only serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is indicated for the treatment of both MDD and FMS is duloxetine. For both MDD and FMS, the recommended dose of duloxetine is 60 mg/day. We have found that patients with comorbid FMS and MDD often require and tolerate 90–120 mg/day.

Although venlafaxine is not indicated for the treatment of any pain conditions, there are reports that it may improve pain and functioning for patients with fibromyalgia (

91), painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy (

92), and chronic pain with associated MDD (

93).

O-Desmethylvenlafaxine, the primary metabolite of venlafaxine, is present in the highest steady-state plasma levels and is the most potent inhibitor of both noradrenaline and serotonin reuptake. This finding is relevant because the reuptake of norepinephrine by venlafaxine, the neurotransmitter with documented analgesic properties (

94,

95), is probably not inhibited at lower doses. For example, relating in vitro reuptake inhibitory concentrations to steady-state plasma concentrations suggests that serotonin reuptake inhibition will be maximal at low doses (<100 mg/day), whereas noradrenaline reuptake can be expected to increase over the dose range from 100 to 400 mg/day (

96). Thus, to achieve noradrenergic blockade with its theoretical greater analgesic effect, venlafaxine doses of at least 100 mg/day are required. Our group has shown that older adults with major depression tolerate doses at least up to 300 mg/day (

97).

Our experience has been to initiate treatment with duloxetine at 30 mg/day or venlafaxine at 37.5 mg/day to reduce the risk of treatment-emergent side effects such as gastrointestinal distress and anxiety. Patients with affective/pain central sensitization syndromes are often exquisitely sensitive to side effects and are quick to discontinue a medication before an adequate trial has been completed. Providing education about side effects so patients are not “taken by surprise” often improves compliance and reduces early medication discontinuation. Discussions with depressed or anxious patients living with chronic widespread pain such as FMS often include a variation of the following: “This medication is an antidepressant that should help your pain, mood, (and/or anxiety). Sometimes people experience an upset stomach, headaches, increased anxiety, and sweating. We'll start this medication at a low dose and increase it slowly to avoid these annoying but not dangerous side effects. If you can stick with taking the medication every day and let me help you manage any of these side effects that should go away by themselves in less than a week, there is a good chance that this medication may help you.”

PHARMACOLOGIC ALTERNATIVES TO ANTIDEPRESSANTS FOR OLDER ADULTS WITH DEPRESSION AND PAIN

Creative treatment planning is often required for older patients living with both depression and chronic pain. As stated above, many of these patients are exquisitely sensitive to medication side effects and are reluctant to try another antidepressant that they feel may have been associated with side effects such as gastrointestinal distress, diaphoresis, akathisia, anxiety, or headache. Although not indicated for the treatment of major depression, trials of anticonvulsant medications and antianxiety agents may improve both mood and pain. For example, valproate, topiramate, and carbamazepine all have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications for the treatment and/or prophylaxis of painful conditions (e.g., migraine or trigeminal neuralgia). These agents have also been observed to improve anxiety (

98–

100). We focus on three medications (gabapentin, pregabalin, and clonazepam) that may improve comorbid chronic pain, depression, and anxiety.

Gabapentin, a calcium channel modulator, has been shown to improve anxiety symptoms (

101) associated with generalized anxiety disorder (

102), panic disorder (

103), and social phobia (

104). In patients with epilepsy, gabapentin has been reported to improve depression (

105). In our own work with older adults living with postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), fibromyalgia, myofascial pain syndromes, and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy and receiving treatment with gabapentin, we have often observed an improvement in mood, anxiety symptoms, and preoccupation with pain that occur simultaneously with analgesia. Although the only FDA-approved pain indication of gabapentin is the treatment of PHN, pregabalin, a medication with a similar molecular structure, is indicated for the treatment of PHN, fibromyalgia, and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Thus, if patients present with a predominantly anxious phenotype and are wary of trying (or trying again) an antidepressant, the use of gabapentin or pregabalin may be a rational choice. To minimize the risks of sedation, lightheadedness, and orthostasis (all of which increase the risk of falls), we increase the dose of these medications slowly in older adults. For gabapentin, we recommend starting at 100 mg/night and increasing by 100 mg/week. We try to get the dose to at least 900 mg/day (if tolerated). For pregabalin, we usually start at 25 mg/night and increase the dose by 25 mg/week to a target of 150–300 mg/day.

In addition to seizure prophylaxis, clonazepam is indicated for the treatment of panic disorder. The decision to use a benzodiazepine in older adults always must be weighed with the increased potential for 1) falls (

106) 2) cognitive impairment (

107), and 3) occult or diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (

108,

109). In addition, potential diversion of controlled substances must be considered for patients of all ages. Although clonazepam has a relatively long half-life, it is not included on the Beer's list of potentially inappropriate medications for use in older adults (

110). With these caveats, we have found that for some older patients living with chronic pain who have comorbid anxiety and depression, parsimonious use of clonazepam can greatly improve the quality of their lives. In particular, we have observed that older patients with myofascial pain syndromes and fibromyalgia, two conditions frequently comorbid with anxiety and depression (

111–

113), may note improvement in both pain and anxiety/depression when treated with clonazepam. We recommend use of the lowest therapeutic doses of benzodiazepines in all patients, but especially in older adults, to minimize the risks described above. For clonazepam, we often start with 0.5 mg/day and increase the dose to 1.5–2 mg/day as needed.

Although pharmacotherapy is almost always indicated for patients living with comorbid depression and widespread pain, there is evidence that disease education (

114), exercise (

115), multidisciplinary pain treatment programs (

116), and cognitive behavior therapy (

117) improve pain, depression, and quality of life.

COMMENT ABOUT OPIOID USE IN OLDER ADULTS WITH DEPRESSION AND PAIN

Depressed older adults living with chronic pain frequently have substandard pain management. For example, in a sample of 1,801 older primary care patients, Unutzer et al. (

118) found that 79% reported functional impairment from pain within the previous month and 57% reported a diagnosis of or treatment for chronic pain within the past 3 years. However, almost half of the sample with functional impairment from pain did not report using analgesic medications. Opioid use varied from 5% to 34% of the sample. Predictors of analgesic use in these depressed elderly patients included a history of chronic pain or arthritis and the degree of functional impairment from chronic pain within the past month.

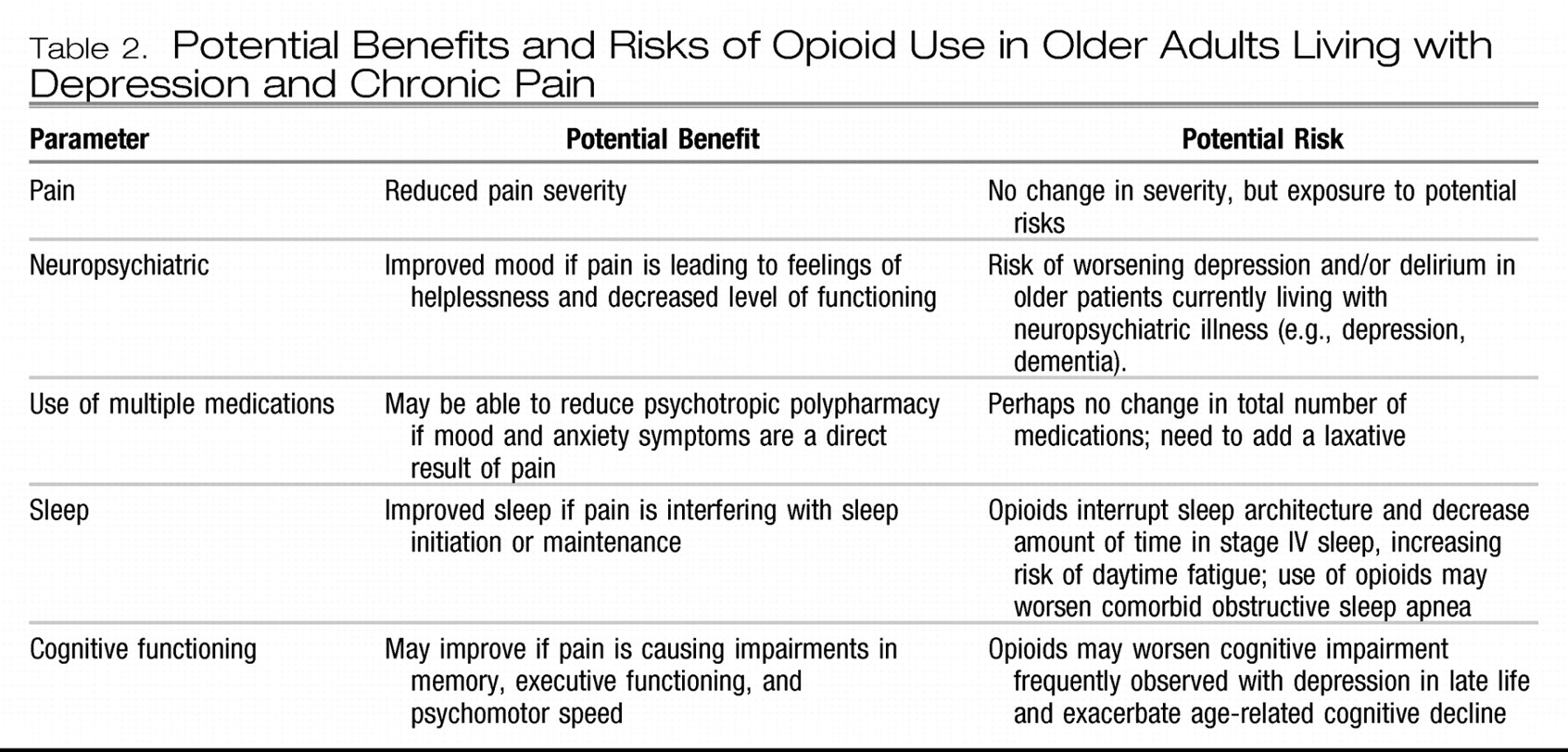

The decision to prescribe an opioid analgesic for an older adult, especially one with depression, always involves a risk-benefit analysis. Potential benefits include decreased pain, improved mobility, and improved cognition. Potential risks of opioid use in older adults, especially those with depression, are a worsening of depression, increased risk of falls, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, impaired cognition, delirium, polypharmacy, constipation, daytime fatigue, medication diversion, and changes in sleep architecture (i.e., less slow wave sleep).

Table 2 lists the pros and cons that should be evaluated in the decision to prescribe an opioid analgesic for an older adult living with comorbid pain and depression.

If the decision is made to initiate treatment with opioids, careful monitoring is critical for both optimizing treatment and assuring safety. The accumulation of metabolites (because of age-related changes in pharmacokinetics) or a direct depressogenic effect of the opioid agent may occur. In addition to potential confusion and delirium, clinicians should monitor for change in depressive symptoms—either worsening or improvement.

Frequent assessment for an appropriate stop date and a plan to terminate therapy with the opioid when it is no longer needed should be in place from the beginning of treatment. For the opioid-naive patient, treatment should be initiated with a low-dose short-acting agent. The choice of potential opioid agents to be used in older adults living with chronic pain and depression who may benefit from treatment with an opioid analgesic is too complex to be covered in this article; readers are referred to the clinical practice guideline published by the American Geriatric Society entitled “The Management of Chronic Pain in Older Persons” (

18).