In current practice, psychiatrists, like other medical professionals, are expected to maintain their specialty expertise in the face of an ever-expanding evidence base. Because a number of studies have demonstrated a gap between recommended evidence-based best practices and actual clinical practice, a variety of strategies have been developed with the aim of improving the quality of clinical care (

1–

10). Proactive approaches to improving quality of care such as the use of clinical reminders (

11–

19) and audit and feedback of practice patterns to practitioners (

12–

14,

19–

22) have resulted in some degree of care enhancement in contrast to the limited success in changing clinician behavior via traditional didactic approaches to education (e.g., CME conferences) (

11–

15,

23–

26). It is also likely that a combination of quality improvement strategies will be essential in promoting substantial improvements in patient care and outcomes (

13,

20,

21,

26–

30).

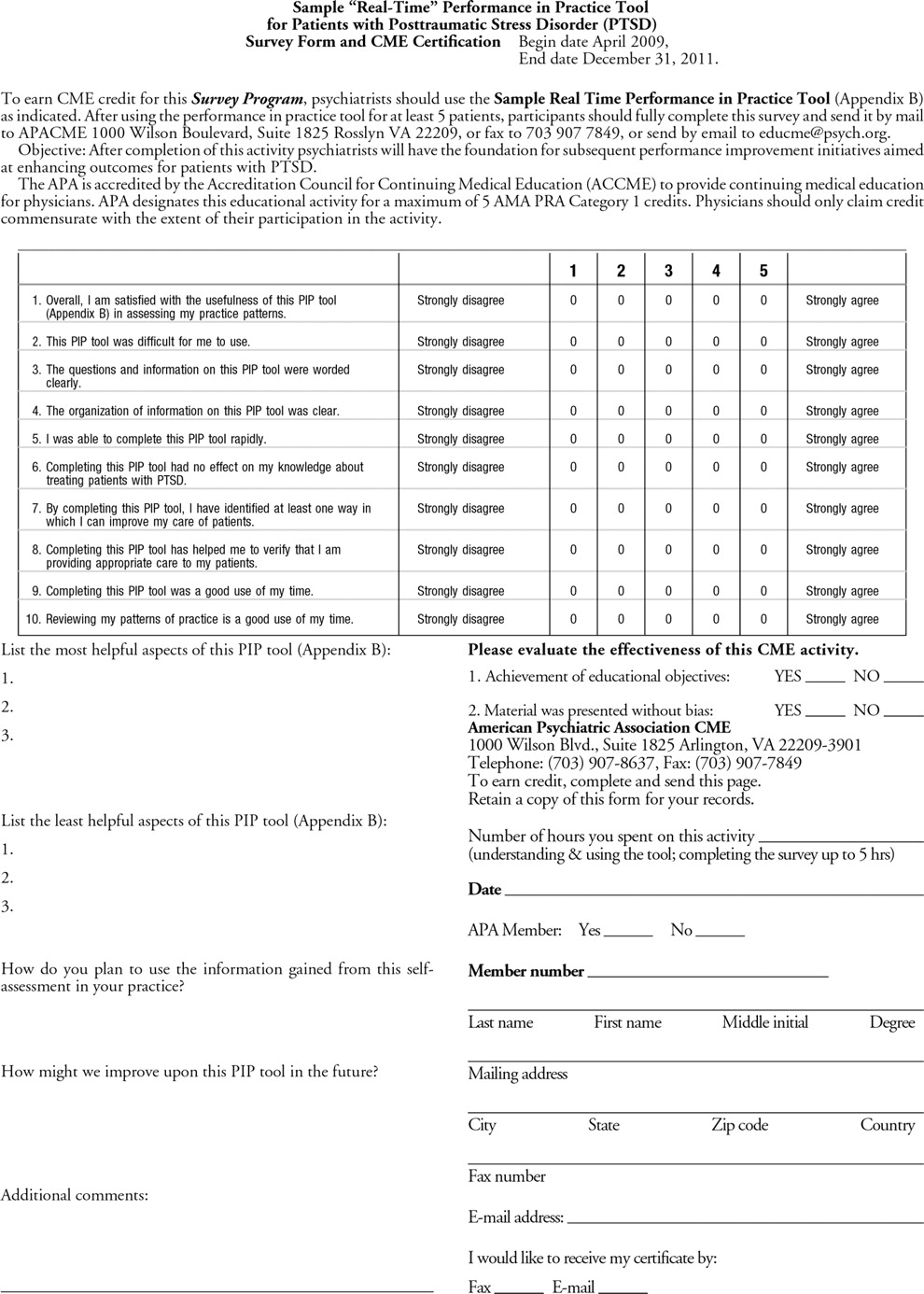

As part of this effort to bridge the quality gap between evidence-based practices and actual clinical practice, the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology are implementing multifaceted Maintenance of Certification (MOC) programs that include requirements for self-assessments of practice through reviewing the care of at least five patients (

31). As with the original impetus to create specialty board certification, the MOC programs are intended to enhance quality of patient care in addition to assessing and verifying the competence of medical practitioners over time (

32,

33). Although the MOC phase-in schedule will not require completion of a Performance in Practice (PIP) unit until 2014 (

31), individual psychiatrists may wish to begin assessing their own practice patterns before that time. To facilitate such self-assessment related to the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), this article will provide sample PIP tools that are based on recommendations of two major guidelines published in the United States: APA's Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (

34) and the U.S. Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense (VA/DoD) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress (

35), supplemented by the latest evidence in the most recent APA Guideline Watch (

36). Other noteworthy practice guidelines for the treatment of PTSD include the Australian guidelines for the treatment of adults with acute stress disorder and PTSD (

37) and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence management of PTSD in primary and secondary care (

38).

The PIP tools described here have been developed to specifically address care of PTSD among adults age 18 years and older; screening, diagnosis, and treatment of PTSD among patients younger than 18 years of age is beyond the scope of this article. A similar set of self-assessment tools for the treatment of depression among adults was published earlier (

39), guided by recommendations from the APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder (

40).

Evidence-based practice guidelines and quality indicators (

41,

42) provide an important foundation for assessing quality of treatment. For a number of reasons, however, the realities of routine clinical practice may temper the development and assessment of a clinically appropriate treatment plan for a specific patient. First, as described previously (

39), evidence-based practice guidelines and quality indicators are often derived from data based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Because patients in efficacy trials and even those in effectiveness trials must meet stringent enrollment criteria, they often differ in important ways from patients seen in routine clinical practice (

43). For example, patients in RCTs are less likely to be suicidal, have co-occurring psychiatric and medical conditions that may interfere with treatment, or be as severely ill as patients in routine clinical practice. Such differences may need to be taken into account when a physician is formulating the best treatment plan for an individual patient.

In addition, when quality indicators are used to compare individual physicians' practice patterns, differences in patient characteristics and illness severity between practices may lead to false conclusions about differences in quality of care. In such circumstances, case mix adjustment is important to address confounding and permit accurate comparison of quality indicator results (

44,

45). Also, inadequate attention to factors such as case mix adjustments may lead to unintended consequences such as excluding more severely ill or less adherent patients from practices in an attempt to improve performance on specific quality indicators. Finally, for patients who have complex conditions or are receiving simultaneous treatments for multiple disorders, composite measures of overall treatment quality may yield more accurate appraisals than measurement of single quality indicators (

46–

48).

Although the above caveats need to be taken into consideration, use of retrospective quality indicators can be beneficial for individual physicians who wish to assess their own patterns of practice. If a physician's self-assessment identifies aspects of care that frequently differ from key quality indicators, further examination of practice patterns would be helpful. Through such self-assessment, the physician may determine that deviations from the quality indicators are justified, or he or she may acquire new knowledge and modify his or her practice to improve quality. It is this sort of self-assessment and performance improvement efforts that the MOC PIP program is designed to foster.

INDICATORS FOR THE EVIDENCE-BASED RECOGNITION AND TREATMENT OF PTSD

The evidence underlying the development of indicators for quality assessment/improvement is generally derived from three sources: 1) experimental studies (e.g., RCTs); 2) epidemiologic or observational studies; and 3) expert consensus. For ASD and PTSD, recent clinical practice guidelines have examined these sources of evidence and have been published in the United States by APA (APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder) (

34) and the VA/DoD (Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress) (

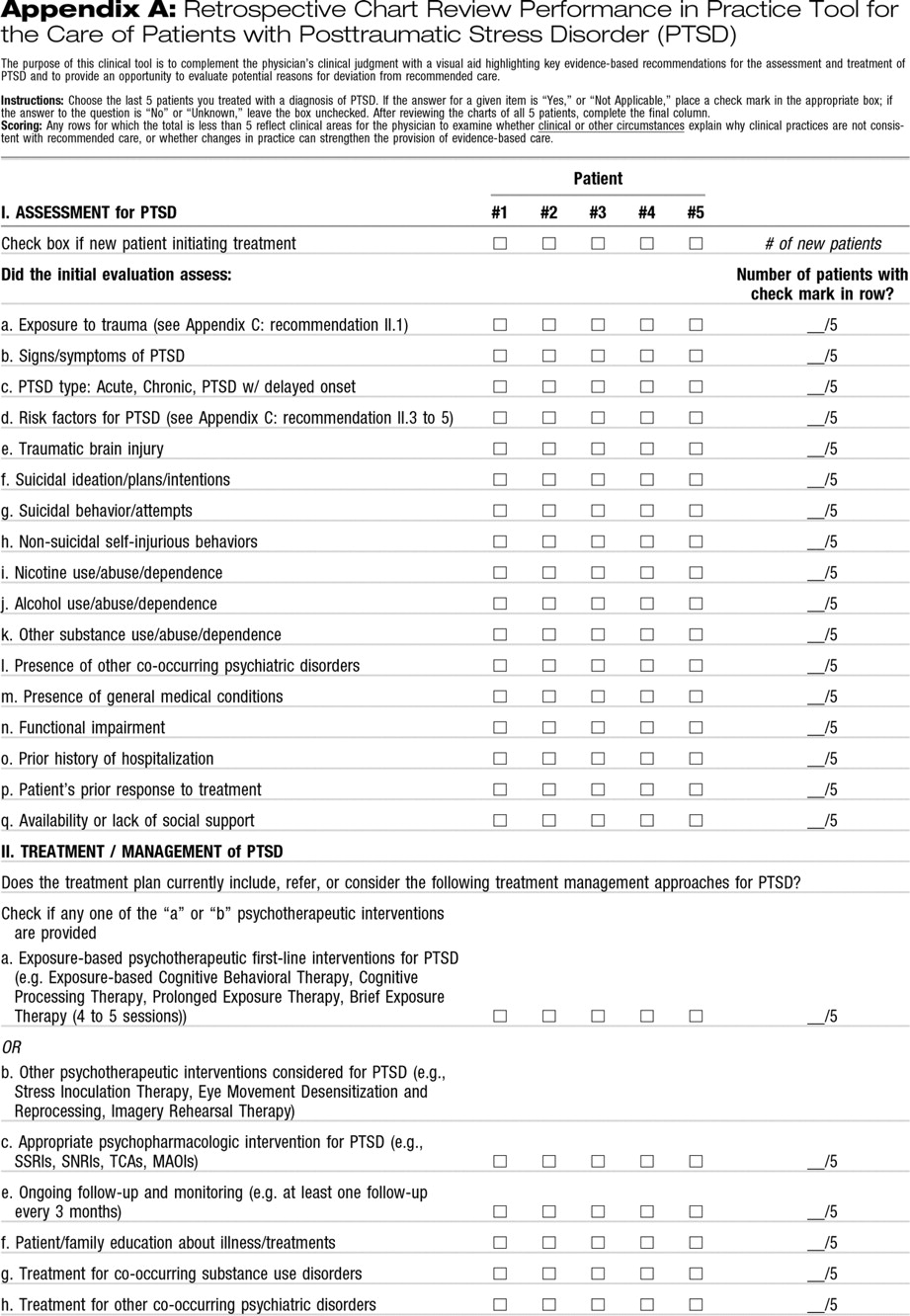

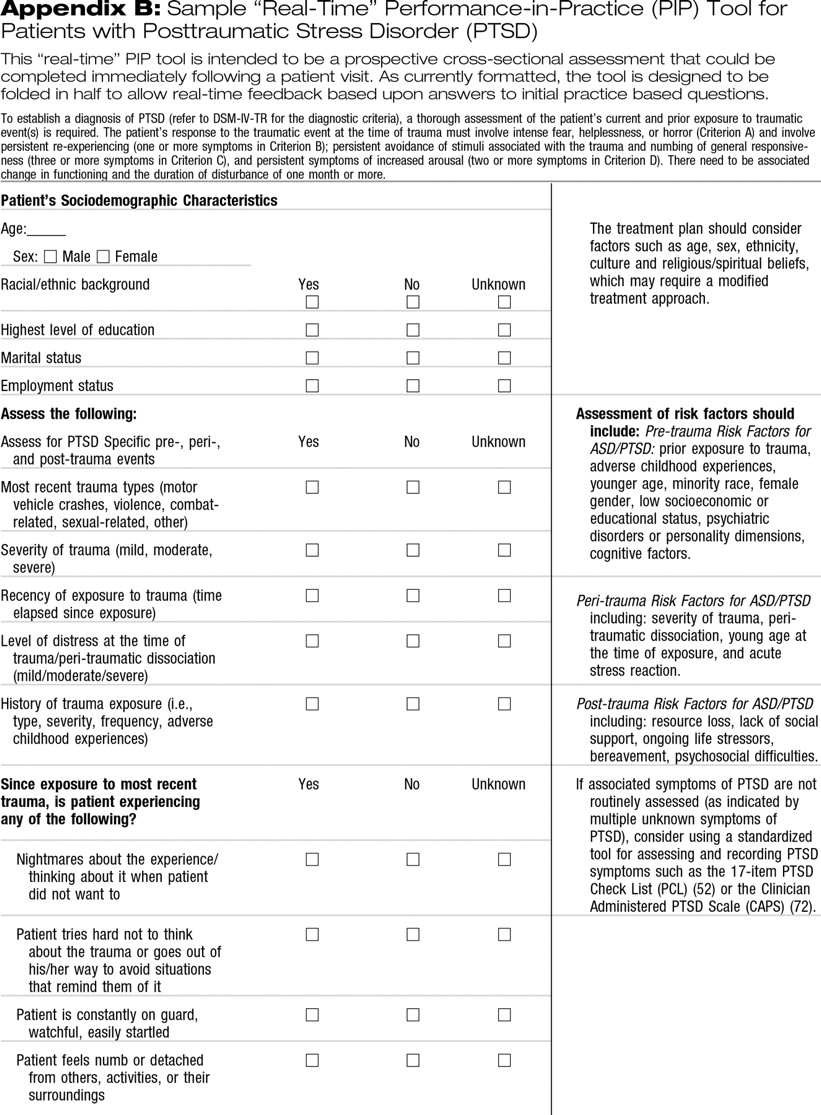

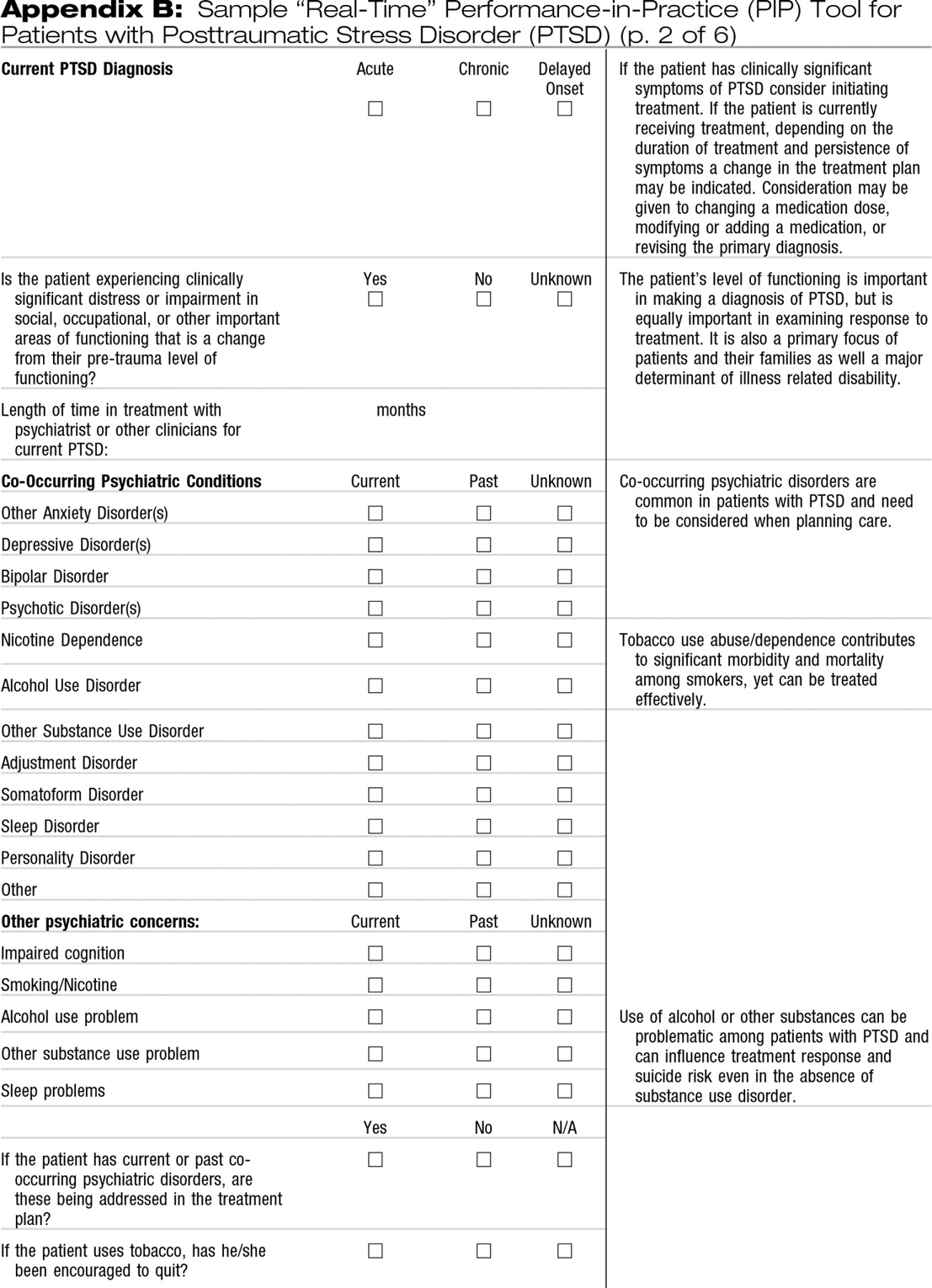

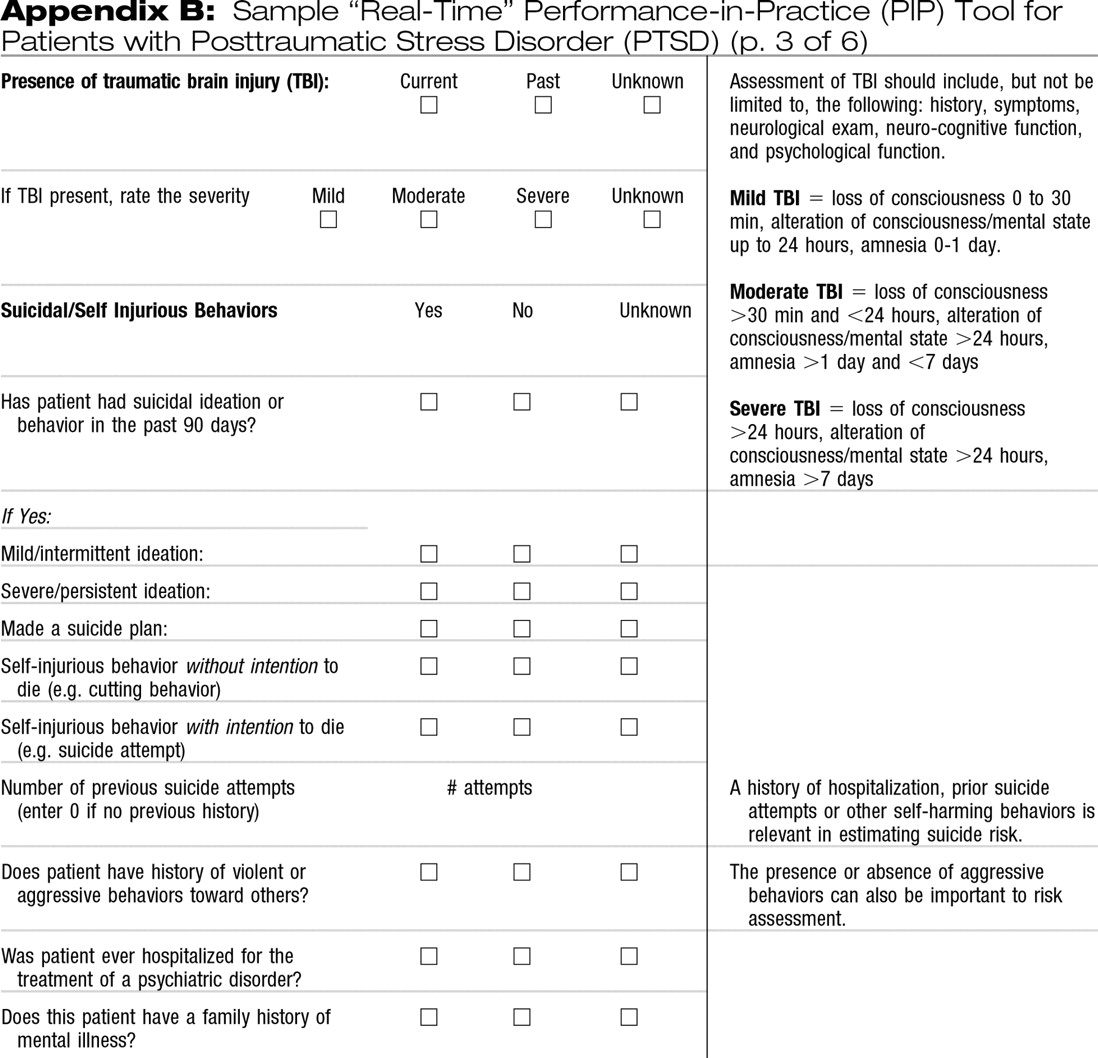

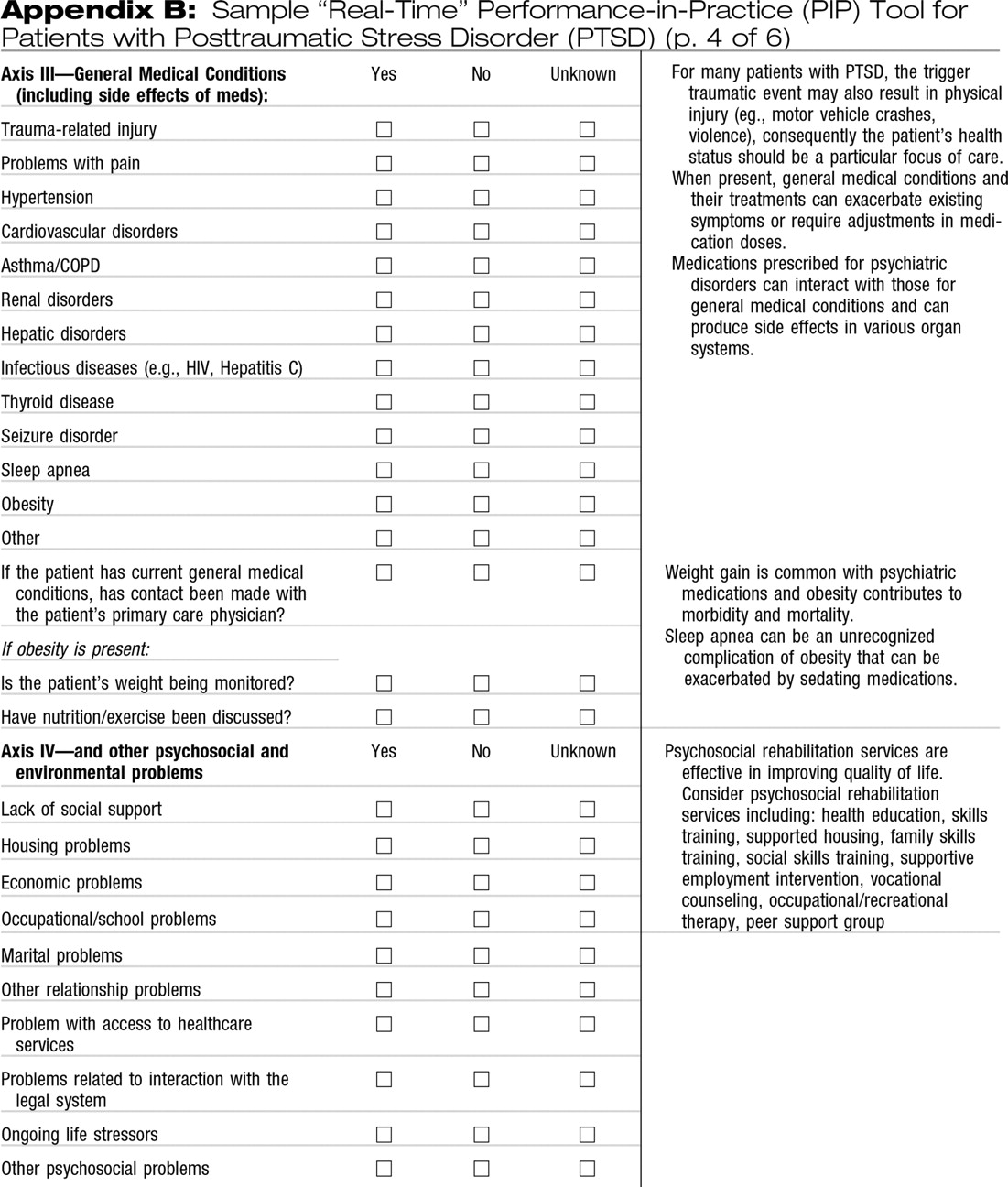

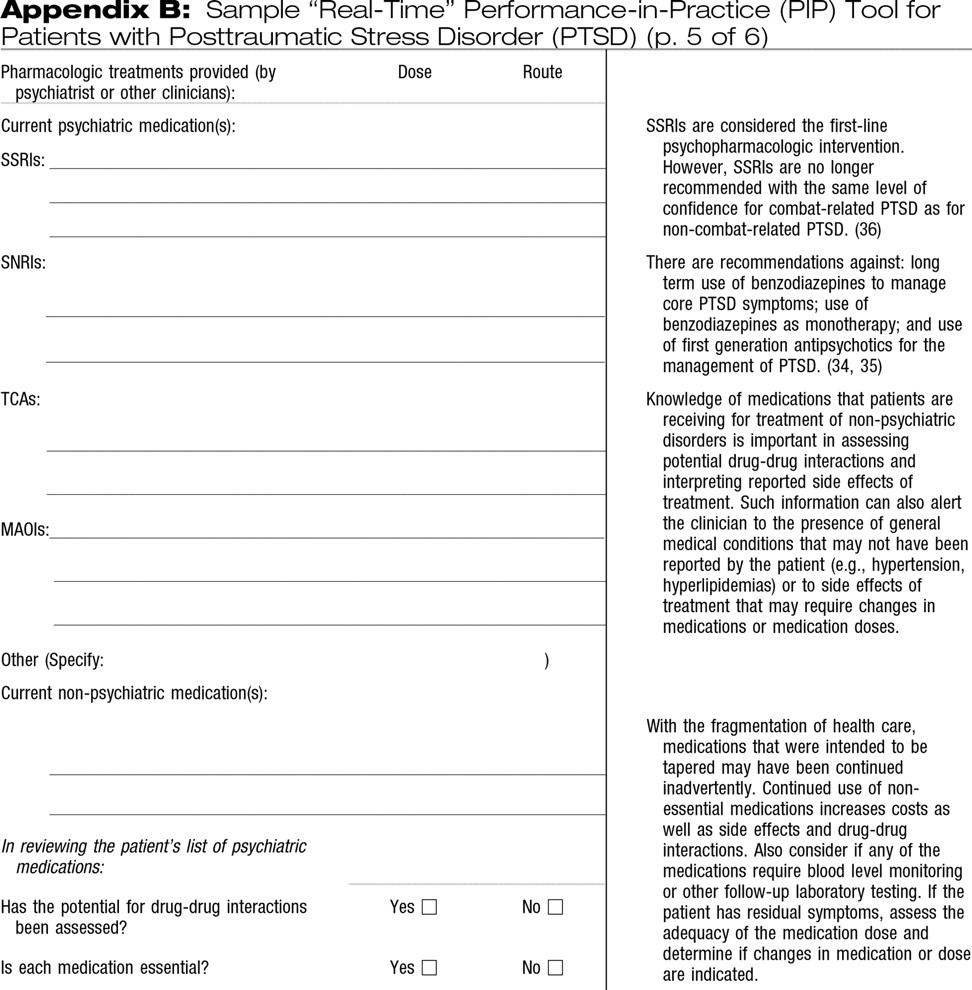

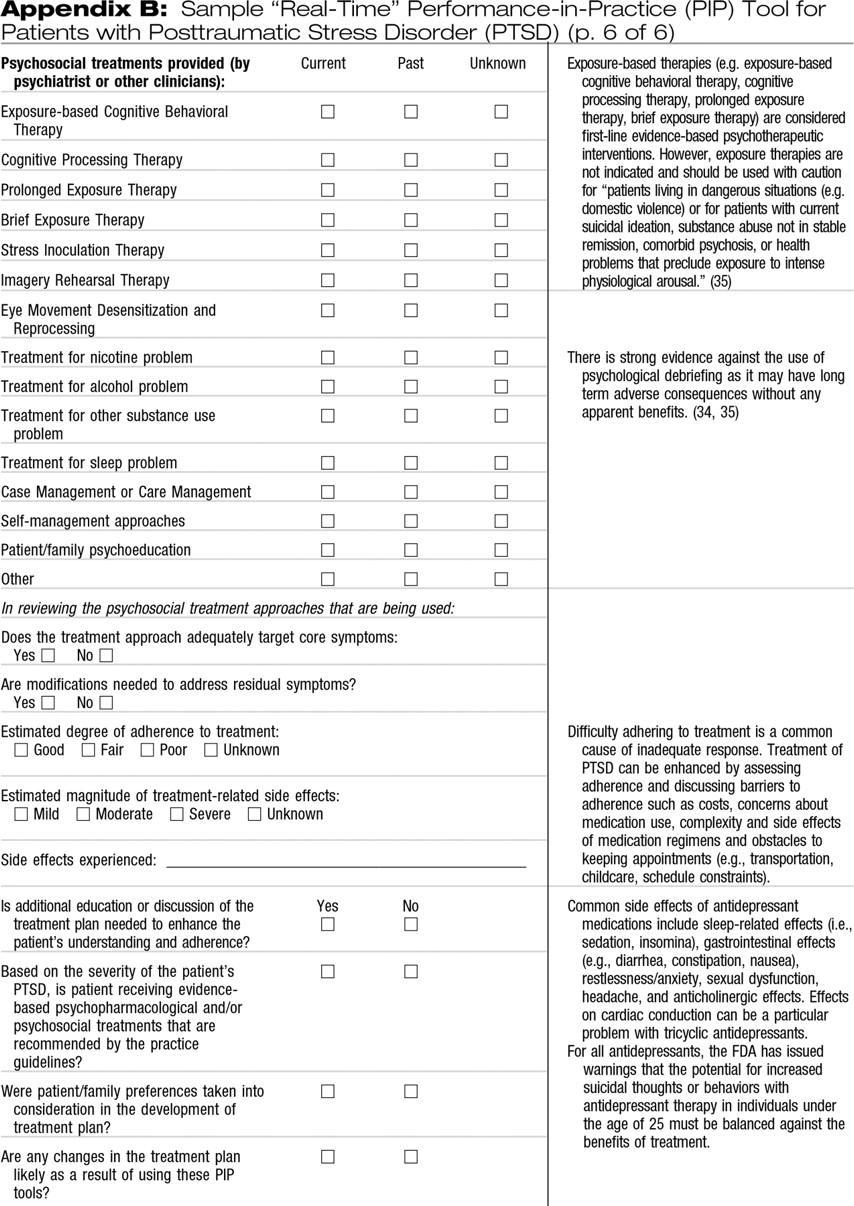

35). The clinical indicators in

Appendixes A and

B are largely derived from these guidelines supplemented with information from a recent Guideline Watch that updates APA practice guidelines (

36) and focuses on recent evidence for pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment for PTSD.

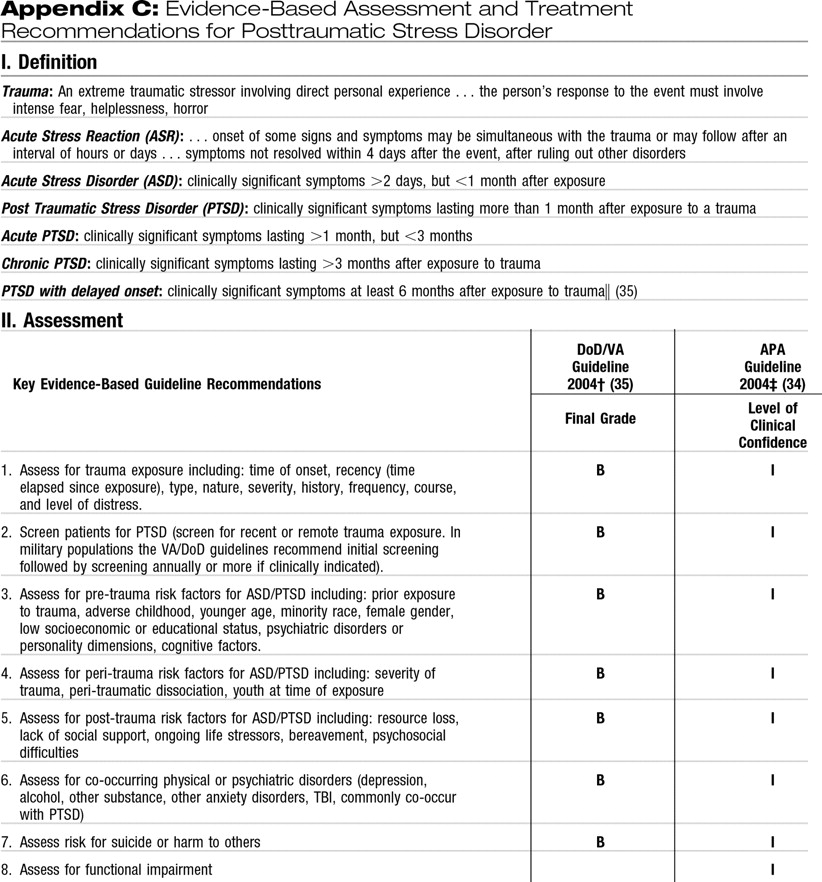

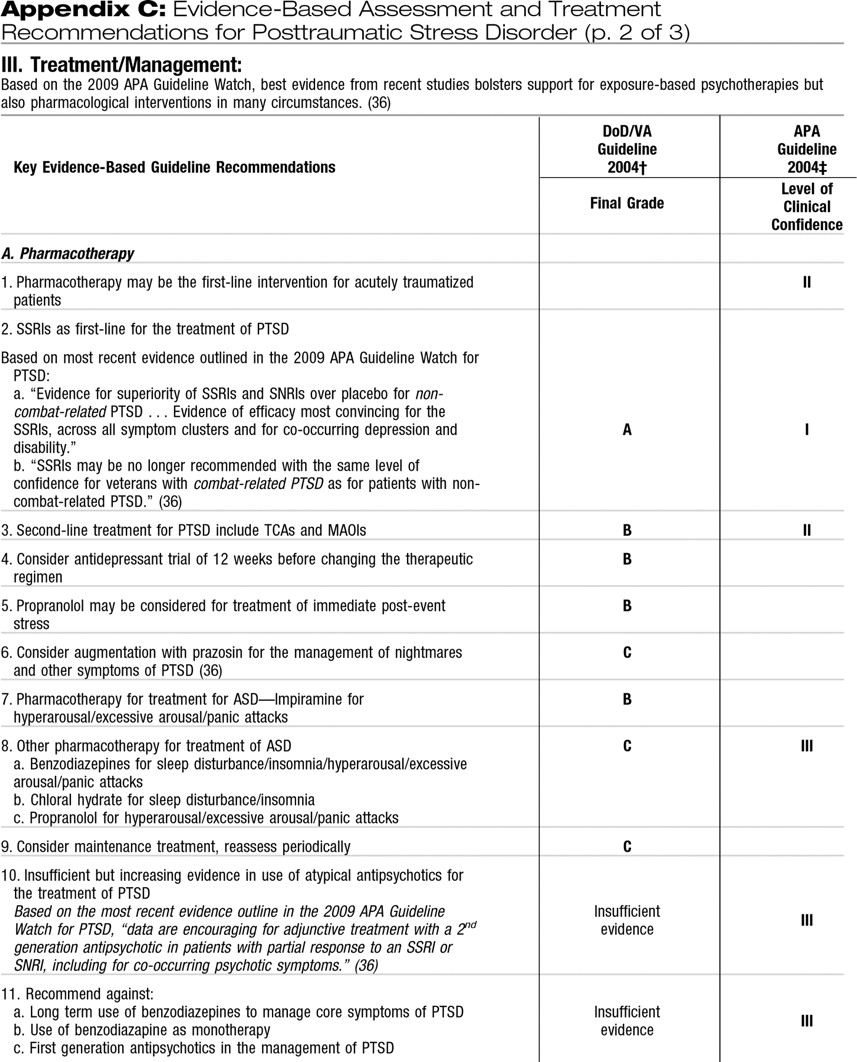

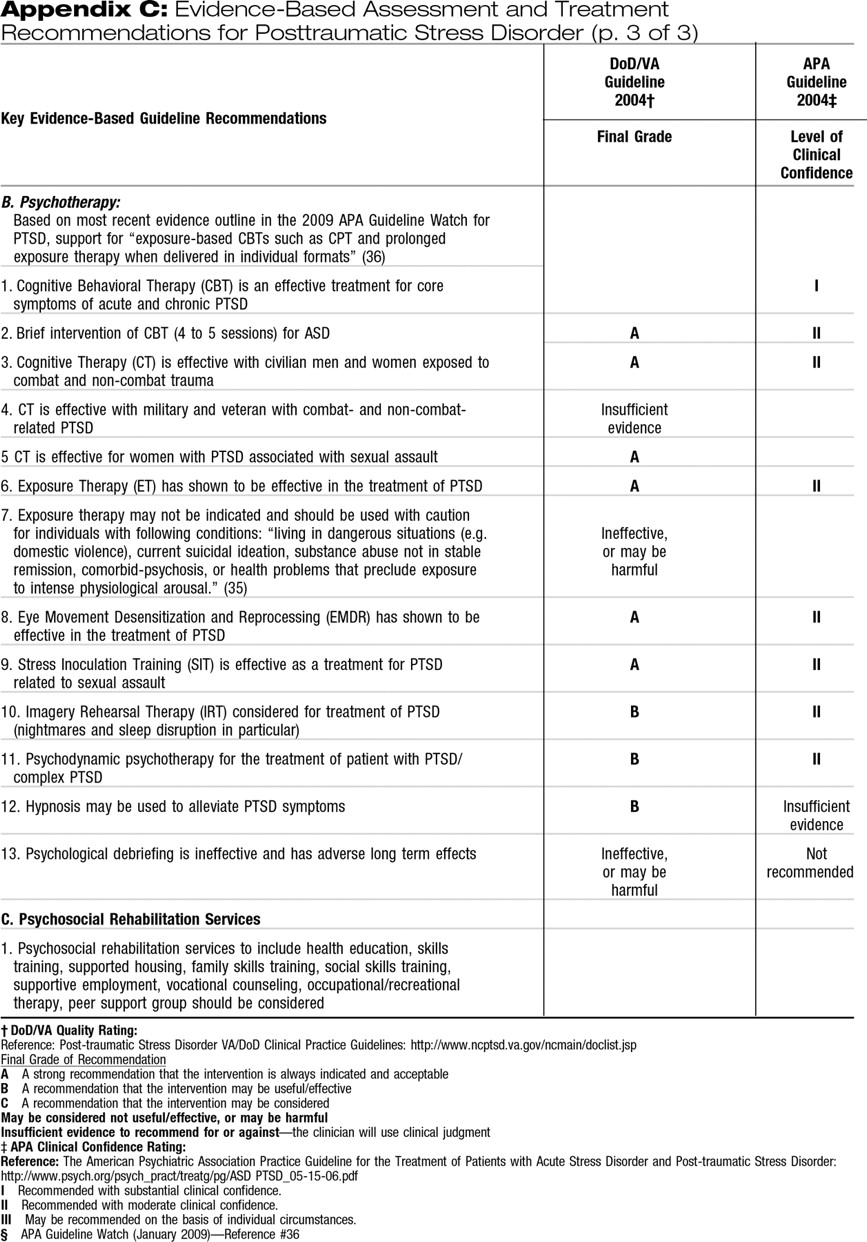

Appendix C highlights key assessment and treatment recommendations derived from the aforementioned guidelines (

34–

36)

INDICATORS FOR SCREENING, ASSESSMENT, AND EVALUATION OF PTSD

The need for screening and diagnosis of PTSD in psychiatric practice is underscored by the substantial prevalence of PTSD in both the general population and in high-risk populations, especially after exposure to specific traumatic events. For example, recent epidemiologic studies using DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria have found the lifetime prevalence of PTSD to range from 6.4% to 9.2% (

49–

51). In addition, women generally have a higher risk of PTSD than men, controlling for type of trauma (

51). These findings support the importance of quality indicators focused on screening for PTSD in the general population using structured instruments such as the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C) (

52). In recent studies of military service members deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, PTSD prevalence rates of 5.0%–19.9% have been found, varying based on strict or broad definition of PTSD using the PCL, deployment location, and pre-post deployment status (

53). In addition, several reports have suggested that routine screening for PTSD can identify subsyndromal PTSD with significant disability at least as frequently as PTSD that meets the full diagnostic criteria (

48,

54,

55).

In addition to routine screening for PTSD in general civilian and military populations, evidence has suggested the need for intensive screening and diagnostic efforts intended for populations with a history of exposure to trauma. For example, elevated rates of lifetime and current prevalence of PTSD have been reported for populations exposed to terrorist attacks [e.g., 12.6% PTSD prevalence among residents of lower Manhattan after the 9/11 attacks (

56) and 31% PTSD prevalence among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing 1 year later (

57)], natural disasters such as hurricanes [22.5% PTSD prevalence after Hurricane Katrina (

58)] and earthquakes [24.2% PTSD prevalence 9 months after an earthquake in China (

59)], and medically traumatic events such as burns [28.6% PTSD prevalence at 1 year (

60)], cancer surgery [11.2%–16.3% 6-month PTSD prevalence after surgery (

61)], acute coronary syndrome [12.2% PTSD prevalence at 1 year (

62)], and hospitalization for traumatic injury [20.7% PTSD prevalence at 1 year (

63)]. An additional consideration is the need for longitudinal screening of trauma survivors because the onset of PTSD symptoms may be delayed for 6 months or more in a substantial number of individuals. More specifically, a systematic review found that “studies consistently showed that delayed-onset PTSD in the absence of any prior symptoms was rare, whereas delayed onsets that represented exacerbations or reactivations of prior symptoms on average accounted for 38.2% and 15.3%, respectively, of military and civilian cases of PTSD” (

64).

Finally, ongoing screening is essential in identifying PTSD in patients being evaluated or seeking treatment for other psychiatric conditions such as psychosis (

65–

67). Also, a substantial proportion of patients with mood and other anxiety disorders also have PTSD. For example, it has been estimated that 7%–40% of patients with bipolar disorder also meet the criteria for PTSD (

68). In addition, the National Comorbidity Survey found the rate of affective disorders to be 4 times higher among respondents with PTSD than among those without PTSD (e.g., 47.9%–48.5% for major depressive episode in subjects with PTSD versus 11.7%–18.8% for those without PTSD) (

49). Similarly, rates of anxiety disorders other than PTSD were twice as high or more among those with PTSD (e.g., 7.3%–31.4% for a variety of specific anxiety disorders) than among those without PTSD (e.g., 1.9%–14.5% for the same range of disorders) (

68). Finally the same study reported alcohol abuse/dependence to be up to twice as high among those with PTSD (e.g., 51.9% for men and 27.9% for women) compared to individuals without PTSD (e.g., 34.4% for men and 13.5% for women) (

49).

TREATMENT INDICATORS

Indicators for assessing the quality of treatment should ideally be derived from experimental treatment trials, preferably RCTs. However, in the absence of such trials, clinicians must rely on clinical experience augmented by data from observational and retrospective studies and expert consensus. Evidence-based practice guidelines provide clinicians with a valuable clinical resource by compiling and processing the most recent scientific knowledge and expert consensus for the treatment and management of selected disorders. Well-established practice guidelines such as those developed by APA and the VA/DoD, that have been referenced here, use a rigorous standardized process for searching the literature, data extraction, and synthesis (

35,

69). For ease of use, recommendations are then graded based on the level of supporting evidence. For example,

Appendix C includes the level of clinical confidence/grade for each of the recommendations based on the VA/DoD and APA practice guidelines, and the definition associated with each level/grade.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

The APA and VA/DoD guidelines uniformly recommend the initiation of serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (SSRIs) as first-line treatment for PTSD (

34,

35). However, the recent Guideline Watch (

36) and Institute of Medicine report (

70), although still supporting use of SSRIs for PTSD among civilians, have found less RCT evidence to support these medications for the treatment of combat-related trauma. There is also less RCT evidence supporting the use of other antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and non-SSRI second-generation antidepressants) (

36). Expert consensus plus observational studies suggest consideration of an antidepressant trial of at least 12 weeks at adequate doses before the therapeutic regimen is changed and consideration of long-term antidepressant maintenance treatment as clinically indicated. In terms of other potential treatment strategies, there is growing evidence to support the use of prazosin specifically for treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares (

71). In addition, recent data suggest that adjunctive treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic agent may be helpful in patients with a partial response to an SSRI or other second-generation antidepressant. However, first-generation antipsychotics should not be used in the management of PTSD. Current evidence also recommends against long-term use of benzodiazepines to manage core PTSD symptoms or as monotherapy, especially given the potential for misuse/abuse and the lack of strong evidence of efficacy. There is, as yet, insufficient evidence to recommend the use of anticonvulsants or primary pharmacotherapeutic prophylaxis of PTSD.

PSYCHOTHERAPY

There is strong RCT evidence supporting the use of exposure-based therapies including exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure therapy, and brief exposure therapy for civilians with PTSD exposed to trauma (both civilian and wartime) and for women with PTSD associated with sexual assault (

34–

36). Current recommendations suggest use of trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy as a first-line treatment for PTSD (

36), which is typically delivered on an individual basis for 8–12 sessions of 90 minutes each (

38). Exposure-based therapies, however, are not indicated and should be used with caution for “patients living in dangerous situations (e.g., domestic violence) or for patients with current suicidal ideation, substance abuse not in stable remission, comorbid psychosis, or health problems that preclude exposure to intense physiological arousal” (

35).

RCT evidence has suggested that eye movement desensitization and reprocessing treatment may be efficacious for PTSD (

36). There is also some RCT evidence supporting the use of stress inoculation therapy for PTSD related to sexual assault (

36). Imagery Rehearsal Therapy may be considered for treating nightmares and sleep disruption associated with PTSD. There is strong evidence against the use of psychological debriefing as it may have long-term adverse consequences and has not shown any apparent benefit.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded in part by the Department of Defense Concept Award Grant #W81XWH-08-1-0399 and the American Psychiatric Foundation Barriers to Care Grant.