The early 1990s witnessed a significant paradigm shift in the practice of clinical medicine and medical education, with greater emphasis given to the individual scientist practitioner's critical appraisal skills and his or her ability to deliver “evidence-based” treatments. For the practicing psychiatrist this poses significant challenges as it requires maintaining a connection with advances in pharmacological and psychological treatments. For many psychiatrists keeping up with the former is much easier than the latter, given the availability of psychiatry online resources, courses, and conferences dedicated to this area. Remaining abreast of developments in psychotherapy seems to be more challenging, perhaps because of the narrow exposure to psychotherapy during training, greater emphasis on pharmacology, and unfamiliarity with resources dedicated to this area, the majority of which are located outside the discipline of psychiatry.

The purpose of this article is to assist the practicing clinician with the difficult task of keeping up with the empirical psychotherapy literature. First and foremost a discussion on how to evaluate the extensive research in this area will be presented with an emphasis on meta-analyses. Second, a brief review of the empirical psychotherapy literature will be presented with a focus on evidence-based psychotherapies for patients with psychiatric disorders. Third, individual variables that predict differential outcomes to treatment will also be discussed as this is an emerging area of research. Fourth, the therapeutic alliance will be briefly discussed as it has remained a robust variable in psychotherapy outcome. Finally, two case examples will be presented to help illustrate how knowledge of the empirical literature can guide evidence-based practice.

EVIDENCE-BASED THERAPIES FOR PATIENTS WITH PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

It is not the purpose of this article to present an exhaustive review of the psychotherapy outcome literature but rather to present a focused review that examines the most recent research. Several narrative reviews that appraise the empirical psychotherapy outcome literature are available (

4). For the purpose of this article, PsycINFO and PubMed were searched using the MESH terms “meta-analyses,” “meta-analysis,” and “review” for the most common psychiatric disorders treated by psychiatrists (i.e., depression, anxiety disorders, and others), and the specific psychotherapies that have recently been associated with successful outcomes with these disorders (i.e., cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and so on). Only the most recent meta-analyses conducted over the past decade (2000–2009) were included as these reviews adhere to more rigorous standards, and earlier studies have been systematically reviewed elsewhere (

5). In total, 67 meta-analyses were found for a variety of psychotherapies across the major psychiatric disorders. Duplicates of meta-analyses by the same author reported in several journals were not included, but rather the most recent one was selected for discussion. All meta-analytic reviews referred to in this article reviewed studies that made comparisons between various control groups such as waiting lists, no treatment groups, and other active forms of treatments. In addition, RCTs that support the use of new emerging therapies (e.g., mindfulness-based cognitive therapy), are also discussed as some of these therapies hold promise for the future if level 1 evidence can be established. Some of these therapies are discussed at length in separate articles in this issue of

Focus.

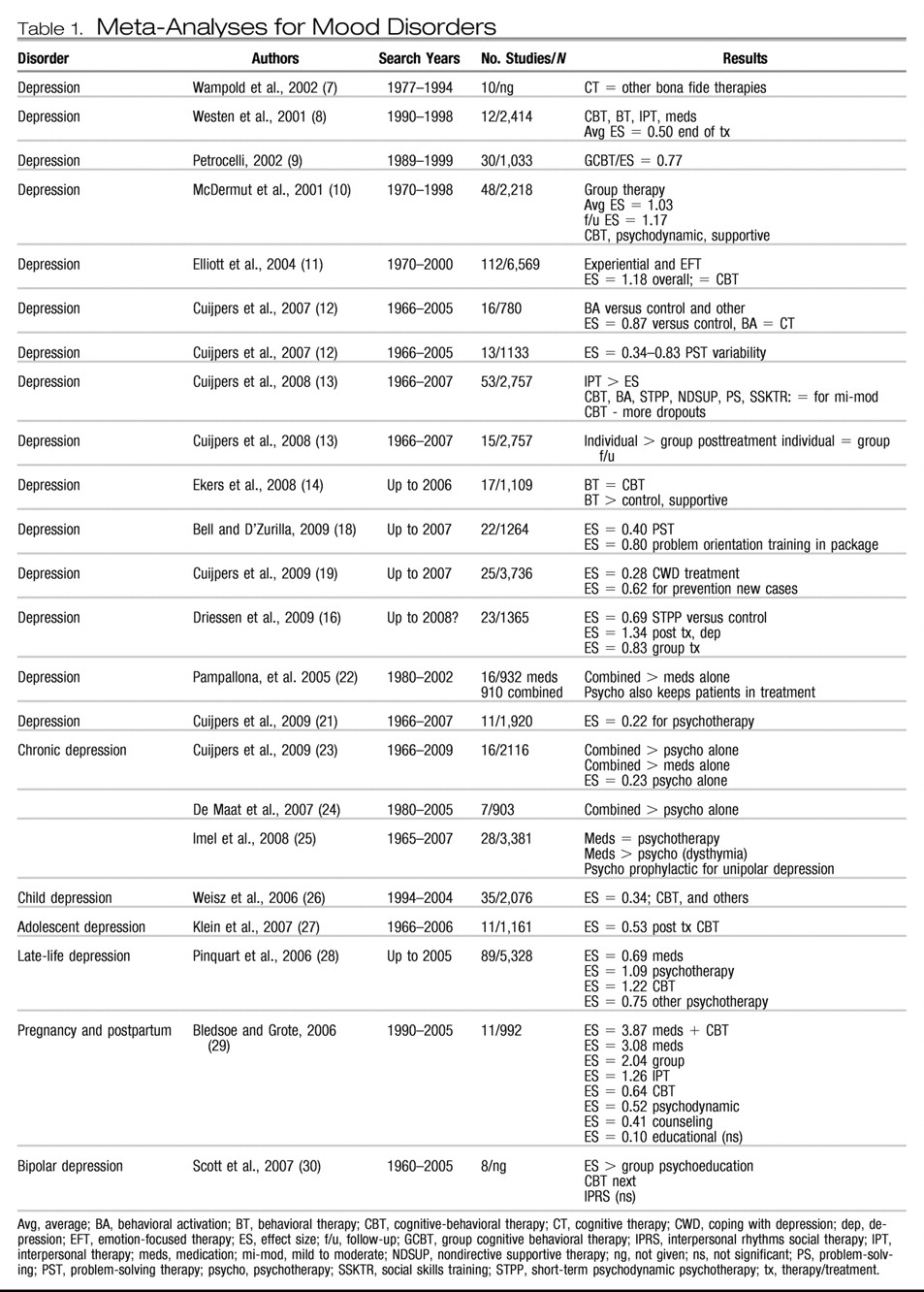

Tables 1 through 6 list the meta-analyses for the common psychiatric disorders for which psychotherapies have been investigated. Each table lists the specific disorder studied, the author(s), search years, number of studies included in the meta-analyses and subjects included if this information is given, and the results reported in effect sizes : either the exact figures or described as small, moderate, or large or percentage improved. If information was missing, authors were contacted by E-mail to provide it, but not all responded. Acronyms are used in the tables, and these are explained in a footnote to the table.

Several meta-analyses have been performed for unipolar depression and other mood-related disorders. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Study set the gold standard for psychotherapy research in the late 1980s (

6). Results revealed positive outcomes for medications (imipramine), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and case management for mild to moderate depression, and superior effects for medication in severe depression and for IPT in the nonfunctionally impaired severely depressed patient. Since the publication of this well-known study, numerous RCTs and several meta-analyses have continued to show positive results for several psychotherapies in the treatment of depression. In the past decade alone, at least 24 meta-analyses demonstrated moderate to large effect sizes for many psychotherapies for depression.

Table 1 shows a range of effect sizes for a variety of psychotherapies for the treatment of depression with large effect sizes noted for CBT whether delivered in individual or group formats (

7–

14). CBT is an integrated therapy in that it incorporates both cognitive and behavioral components in the conceptualization of patient problems and in the delivery of treatment. The fundamental premise of CBT is that psychological distress, whether it is manifested in mood, anxiety, or other problematic symptoms, is a result of specific maladaptive thought processes, which in turn lead to difficulties in emotions and behavior. Treatment includes challenging these distortions in the context of a collaborative relationship and a positive therapeutic alliance. Self-monitoring and behavioral techniques that incorporate specific homework exercises expose the patient to alternate interpretations of events and help change behavior in a positive direction. Helping patients to increase positive events in depression and decrease avoidance in anxiety (i.e., exposure) reduces maladaptive symptoms.

Large effect sizes have also been reported for IPT especially for patients with certain psychosocial stressors and “obsessional” personality traits (

15). IPT is a brief, structured, integrative therapy originally developed for patients with depression. The fundamental assumption in IPT, is that the onset of, maintenance of, and recovery from depression is determined by four key interpersonal events: losses, role transitions, interpersonal conflicts, and interpersonal deficit. Therapy focuses on integrating a medical model of depression as well as understanding and working through these key interpersonal areas.

Newer therapies such as behavioral activation and emotion-focused therapy (EFT) also demonstrate large effect sizes (

11–

12,

14). Behavioral activation is based on behavior theory and involves activity scheduling and the introduction of positive reinforcing events. Behavioral activation can be integrated with medications and other psychotherapies and is an easy-to-administer treatment requiring much less therapist training than the other psychotherapies. However, given the demand for participation in activities, patient compliance is crucial. EFT is an experiential therapy that integrates client-centered and gestalt techniques and is extensively described in a separate article in this issue. This therapy has been studied in RCTS as well as in a meta-analysis (

11) and has been found to be helpful in the treatment of depression, with improvements in self-esteem and interpersonal problems noted in the long term.

A recent meta-analysis also showed moderate to large effect sizes for short-term psychodynamic therapy (STPP), better known as brief psychodynamic therapy, which incorporates the active ingredients of change of long-term psychodynamic therapy but in a briefer format. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy involves a heterogeneous group of treatments that focus on transference, defenses, or other intrapsychic conflicts. Interventions in STPP can focus on either supportive or expressive dimensions, with evidence supporting both as active ingredients of change in the outcome of treatment (

13,

16).

Problem-solving therapy and the coping with depression (CWD) psychoeducation package have also been investigated in the treatment of depression. Both therapies are brief and active and engage the patient in working through difficulties in a systematic manner to learn specific skills that can be used when dealing with depressive symptoms. Both treatments show small effect sizes as a treatment for depression, although CWD appears to be effective as a preventative measure for future episodes (

13,

17–

19). However, a component analysis has revealed that the problem orientation package of problem-solving therapy has a much higher effect size than the complete package, raising issues as to which ingredients act as mechanisms of change in this form of treatment.

Of significance is a recent comparative meta-analysis by Cuijpers et al. (

13), who found that although CBT, IPT, behavioral activation, short-term psychodynamic therapy, nondirective supportive therapy, problem-solving therapy, and social skills training were all effective for mild to moderate depression, IPT had a slight advantage and problem-solving therapy showed the fewest dropouts. Cuijpers et al. (

20) also found that individual treatment produced better outcomes than group treatment at the end of treatment, but no significant difference was noted at follow-up. In a recent article in which highly stringent criteria were applied to the selection of studies, resulting in only 11 RCTs, a lower effect size was found for psychotherapies for the treatment of depression (

21). Although this result requires replication, it is important to note that the use of highly stringent criteria excludes many well performed RCTs that have clearly established effectiveness.

The above meta-analyses have focused primarily on unipolar mild to moderate depression and have essentially established what was concluded in the early NIMH trials: most psychotherapies seem to be generally effective in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Three meta-analyses have looked at chronic severe depression or dysthymia and have generally all found the same results: combined treatments that include medication and psychotherapy fare better than psychotherapy or medication delivered alone (

22,

23,

25). This result probably comes as no surprise to the clinician who finds that these patients are more resistant to medications as well as to psychotherapy, thereby requiring an integration of both treatments. An additional meta-analysis showed superior outcomes with combined treatment than with medication alone, and patients remained in treatment longer if psychotherapy was integrated into the treatment plan (

24).

Meta-analyses have also been conducted for childhood and adolescent depression, late-life depression, pregnancy and postpartum depression, and bipolar depression. In childhood depression effect sizes have been small at best, but recent studies showed moderate effect sizes in adolescent depression with greater than half of patients improving with CBT (

26,

27). In the late-life period CBT and other “psychotherapies” grouped together showed high effect sizes (

28). These psychotherapies included supportive, psychodynamic, and other treatments. Bledsoe and Grote (

29) conducted a meta-analysis comparing several psychotherapies in the pregnancy and postpartum period and found large effect sizes for medication plus CBT, group therapy, and IPT, with moderate effect sizes for CBT and psychodynamic therapy, and small effect sizes for counseling and psychoeducation. The poorest results were found for bipolar depression for which large effect sizes have been found for psychoeducation and moderate effect sizes for CBT for enhancing medication compliance. Nonsignificant results have been found for interpersonal social rhythms therapy, a form of IPT (

30).

Although many therapies have been found to be effective for depression post-treatment, many patients continue to have residual symptoms and tend to relapse. Therefore, neither psychotherapy nor medication provides a cure, but both treatments can be integrated in an evidence-based, patient-directed manner to provide the best outcome. Several psychotherapies such as CBT and IPT have focused on relapse prevention by increasing sessions, providing “booster” sessions, and focusing on prevention techniques. Because of the limitations of traditional cognitive therapy, new variants of CBT have emerged over the last two decades. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has recently been investigated for those patients with three or more episodes of depression and shows promise in four recent clinical trials (

31). Mindfulness is not a specific form of therapy but an ancient Buddhist meditative technique. When practiced frequently, mindfulness produces a state of nonreactivity and detachment from disturbing thoughts and feelings that lead to depression, anxiety, and emotional dysregulation. There are many exercises that are considered “mindfulness” based. Some of these involve paying attention to the breath, attending to the moment, or focusing on an object. Mindfulness is an intriguing approach not only for chronic depression but also for other psychiatric disorders and its application in psychiatry is discussed in detail in a separate article in this issue.

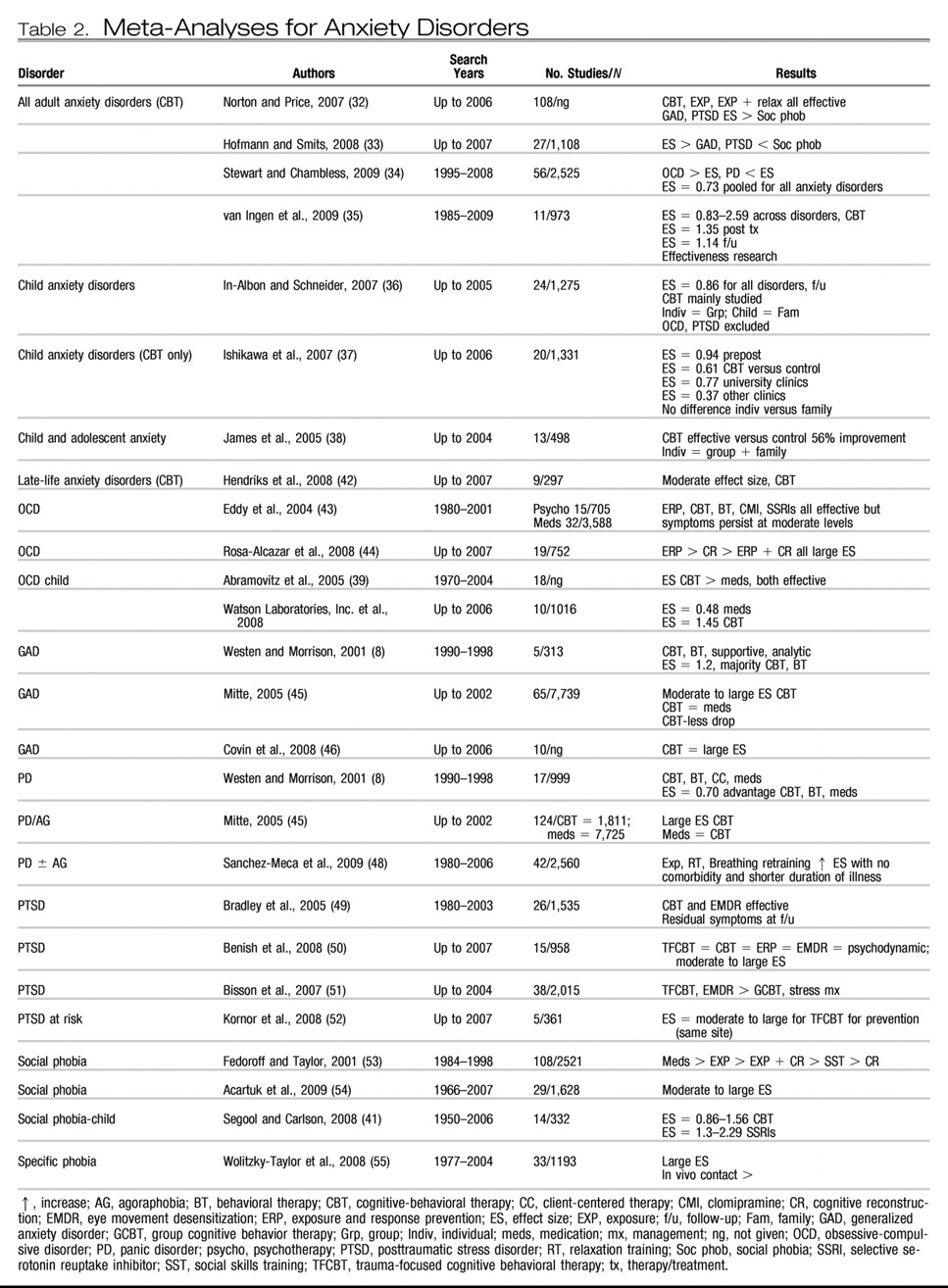

Unlike for depression, there are few comparative trials of psychotherapy in the treatment of anxiety disorders. The majority of studies have compared medications, CBT, components of CBT (e.g., exposure, exposure and response prevention, and behavior therapy), relaxation, and eye movement desensitization reprocessing (EMDR) with wait list controls. There is heavy emphasis on the behavioral component of CBT in the treatment of anxiety disorders as patients are encouraged to “expose” themselves to the feared situation and not engage in avoidance. In EMDR patients are asked to recall a traumatic memory, and lateral sets of eye movements are induced by the therapist who moves his or her finger across the patient's field of vision. The patient is then asked to report any feelings, thoughts, or images that arise, which then become the focus of the next set of eye movements. This process continues until the distress evoked by the memory diminishes.

Table 2 shows 27 meta-analyses over the past decade for all anxiety disorders across the lifespan. When all anxiety disorders are combined, moderate to large effect sizes are evident for the treatment of all adult anxiety disorders with some studies showing large effect sizes for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and lower effect sizes for social phobia (

32–

35).

Large effect sizes have also been found for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders with CBT, with individual treatments equaling family treatment or group treatments, university clinics producing moderate effect sizes, and community clinics showing small effect sizes (

36–

38). These findings could indicate that CBT performed in the “real-world” community clinic is less effective, possibly due to several factors such as severity of illness, decreased therapist competency, or decreased therapist adherence to CBT interventions and poor patient compliance with treatment. Separate meta-analyses have been conducted for childhood OCD and social phobia, again showing large effect sizes with CBT treatments (

39–

41). Moderate effect sizes have also been found for CBT for late-life anxiety disorders (

42).

With respect to specific adult anxiety disorders two recent meta-analyses showed very large effect sizes for exposure and response prevention and medications for OCD; however, symptoms do persist at moderate levels after treatment (

43,

44). The treatment of GAD with CBT, behavior therapy, or medications also demonstrates high effect sizes, with small to moderate effect sizes for supportive and psychodynamic treatments (

8,

45,

46). Moderate to large effect sizes have also been found for CBT and medications in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, but this effect seems to decrease with increasing comorbidity and longer duration of illness (

8,

47,

48). Trauma-focused CBT and EMDR seem to have larger effect sizes as indicated in more recent meta-analyses, although controversy regarding EMDR as a treatment for PTSD still exists (

49–

52).

In social phobia moderate to large effect sizes have been found for both CBT and medications (

53,

54). In addition, dismantling studies have shown that exposure alone is superior to exposure combined with cognitive reconstruction and social skills training (

53). The treatment of specific phobias with in vivo exposure interventions also indicates large effect sizes (

55). Therefore, at the present time CBT remains the mainstay of treatment for patients with anxiety disorders with moderate to large effect sizes demonstrated for different anxiety disorders across the lifespan. However, residual symptoms are prominent with increasing symptom severity and comorbidity, once again suggesting longer treatment and possibly combined treatment with medication for optimal response in the long term (

49)

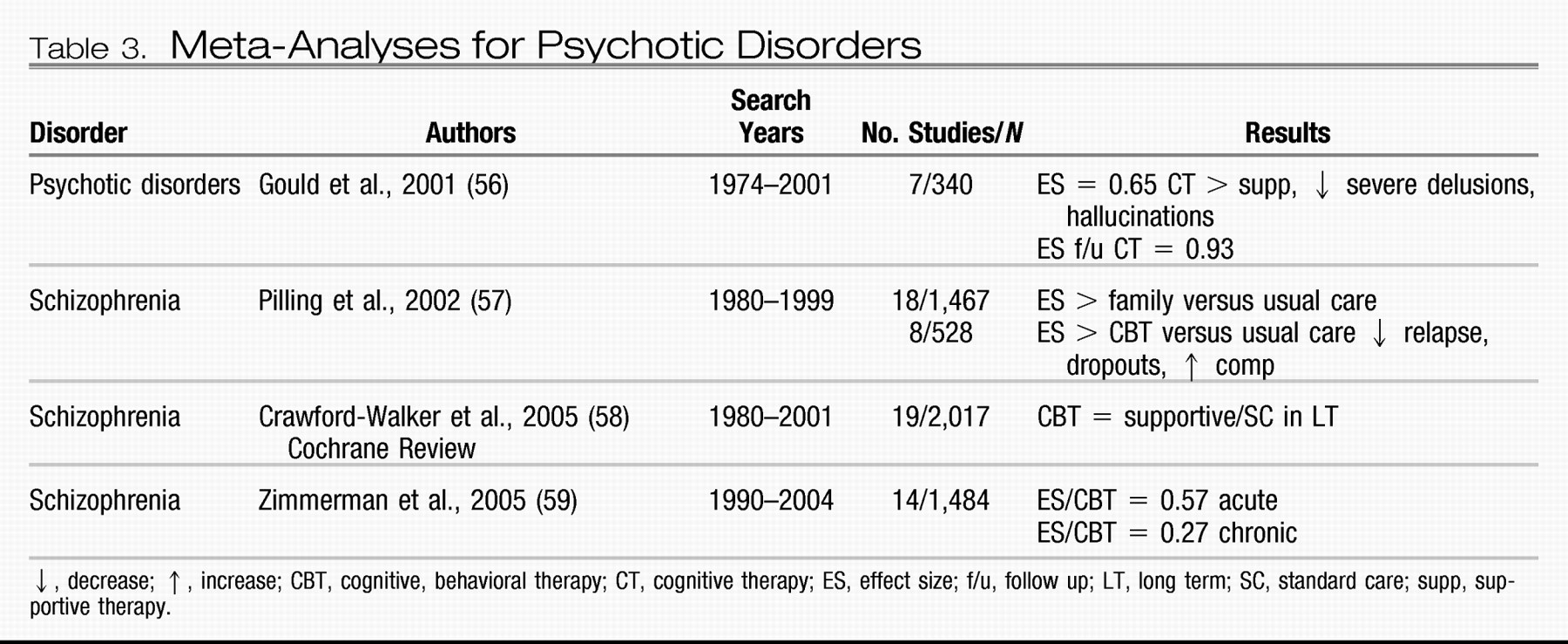

CBT has recently been investigated for psychotic disorders with two meta-analyses showing moderate to large effect sizes for decreasing patient distress associated with psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions (

Table 3 Gould et al.) (

56) found a moderate effect size in decreasing distress associated with psychotic symptoms after treatment with CBT compared with supportive therapy. However, a much larger effect size was found for CBT at follow-up. Pilling et al. (

57) also found large effect sizes for CBT compared with usual care in decreasing relapse and dropouts, and increasing medication and treatment compliance in patients with schizophrenia. Zimmerman et al. (

59) found a moderate effect size for CBT for acute psychotic symptoms and a small effect size for chronic psychosis. However, a recent Cochrane review did not find any difference between CBT and supportive therapy in the long term, indicating that more work may be needed in this area (

58).

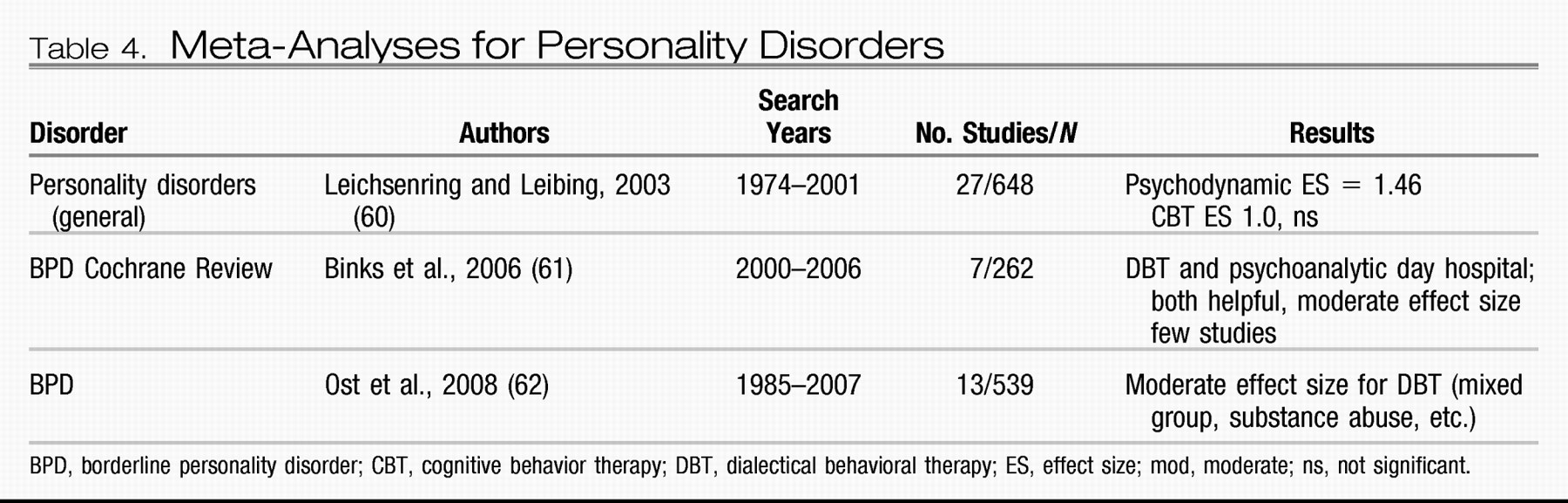

Few meta-analyses have been conducted for personality disorders, given the limited research in this area, with the exception of borderline personality disorder (BPD) (

Table 4). Leichsenring and Leibing (

60) found large effect sizes for both psychodynamic therapy and CBT for the treatment of a variety of personality disorders. Two meta-analyses were conducted for BPD with comparisons being made between dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and psychoanalytic day hospital treatment. DBT is an integrated treatment that incorporates techniques from CBT and mindfulness to promote emotion regulation and to decrease impulsivity leading to self-injurious behavior. Binks et al. (

61) found moderate effect sizes for both DBT and psychodynamic therapy with only a few studies in their analyses. Psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization treatment was found to be helpful in patients with BPD, with an advantage noted over DBT in decreasing parasuicidal behavior and hospital admissions (

61). A more recent meta-analysis found a moderate effect size for DBT; however, the sample consisted of patients from mixed diagnostic groups (i.e., substance abuse and others) (

62).

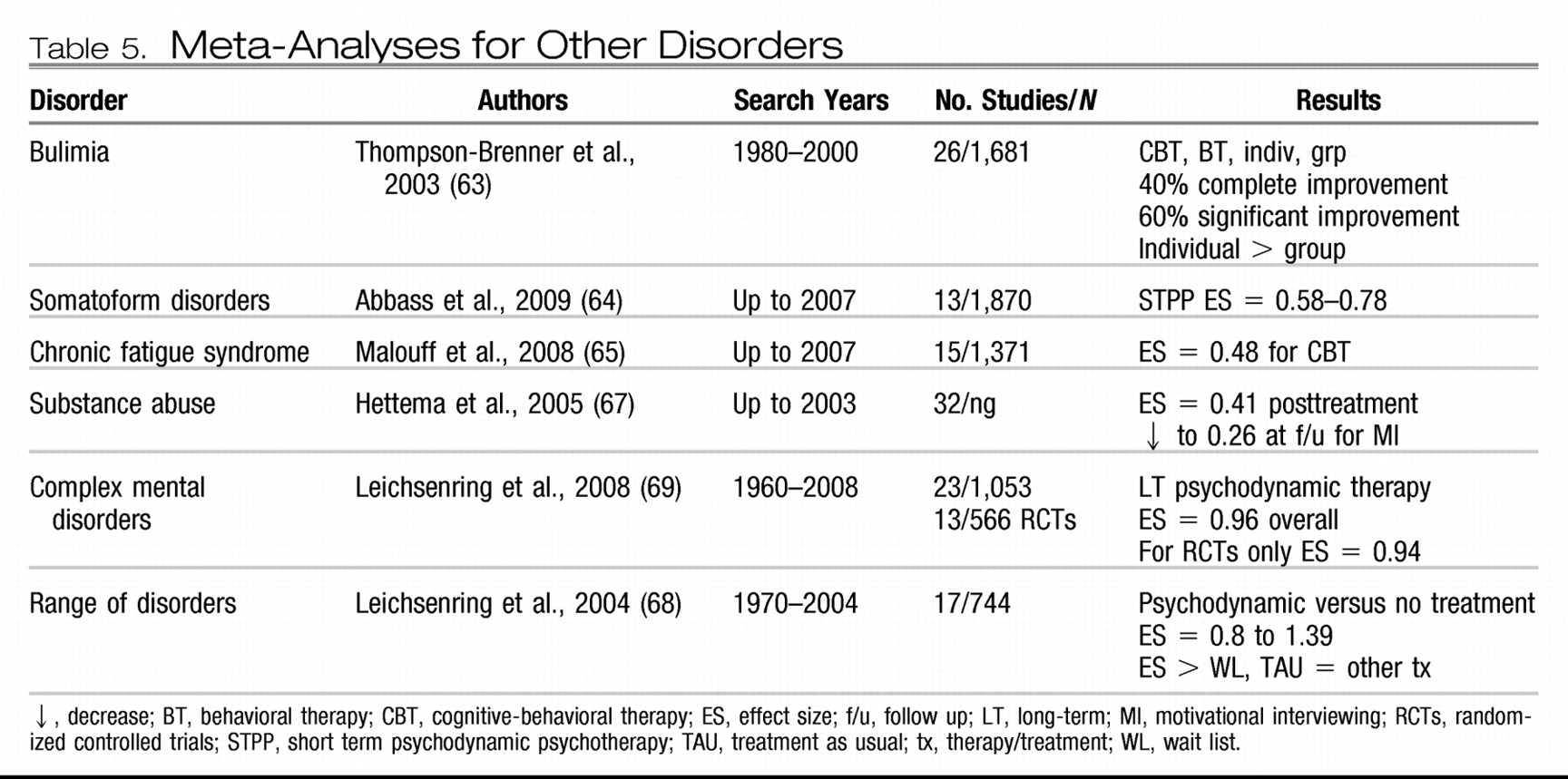

Meta-analyses have also been reported for other psychiatric conditions (

Table 5). Moderate effect sizes have been reported for CBT and behavior therapy with individual and group treatment of bulimia (

63). Abbass et al. (

64) found a moderate effect size for short-term psychodynamic therapy for the treatment of somatoform disorders, whereas Malouff et al. (

65) found a small to moderate effect size for treating chronic pain with CBT, which has been reported in other studies (

66). Moderate to large effect sizes have also been reported for motivational interviewing (MI) for patients with substance abuse, although these effects seem to decrease over time (

67), suggesting the need for “booster sessions,” which are essential in many chronic conditions. MI is a specific interviewing technique with the aim of assessing a patient's readiness to change and engage in treatment. MI uses an open dialogue to explore whether a patient is ready to commit to treatment. The therapist is nonjudgmental, empathic, and respectful of the patient's current status. An interesting finding is that this intervention appears to have a greater effect on certain minority populations and may be considered a suitable “match” in such cases.

Leichsenring and colleagues (

68,

69) reported two meta-analyses for a range of disorders and complex disorders treated with psychodynamic therapy and found large effect sizes compared with wait list or treatment as usual. When only RCTs were included, the effect size remained significant and large (

69). In addition to this finding, effectiveness research supports the use of long-term psychodynamic therapies in decreasing symptomatic distress and improving interpersonal problems, social adjustment, and self-esteem (

69). The last decade has witnessed an emergence of research in psychodynamic therapy, suggesting that this therapy is a viable option for interpersonal and characterological difficulties that cannot be treated by other briefer treatments focusing on symptomatic improvement. Further research may also establish brief dynamic therapies as beneficial alternative treatments in some axis I disorders when other treatments fail.

A group of treatments known as the “third-wave cognitive behavior therapies” have also been investigated for many conditions. Therapies under this umbrella include acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (which incorporates acceptance and mindfulness strategies, together with commitment and behavior change strategies to increase psychological flexibility) for the treatment of depression, anxiety, stress, and addictions; DBT for patients with BPD as discussed above; the cognitive behavior analysis system of psychotherapy (which integrates components of cognitive and psychodynamic therapy) for chronic depression; functional analytic psychotherapy (which incorporates radical behaviorism to in-session verbal behavior) for depression; and integrative behavioral couple therapy (which integrates behavioral couple therapy with emotional acceptance) for couple problems. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated moderate effect sizes for both ACT and DBT, but because of the small number of studies conclusions regarding the other therapies cannot be made at this time (

62).

Although not incorporated in recent meta-analyses, two new therapies show promise in the treatment of patients with BPD: systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS) and schema-focused therapy. STEPPS is a brief therapy that incorporates CBT, skills training, and systems theory and has been found to be effective in RCTs in the treatment of BPD (

70). Schema-focused therapy, a form of CBT that focuses on core beliefs and schemas developed in childhood, has also been found to be helpful in treating patients with BPD (

71). Meta-analyses of the future will no doubt include these new forms of treatments and it is hoped that they will offer patients with BDT a wide range of psychotherapeutic options to choose from.

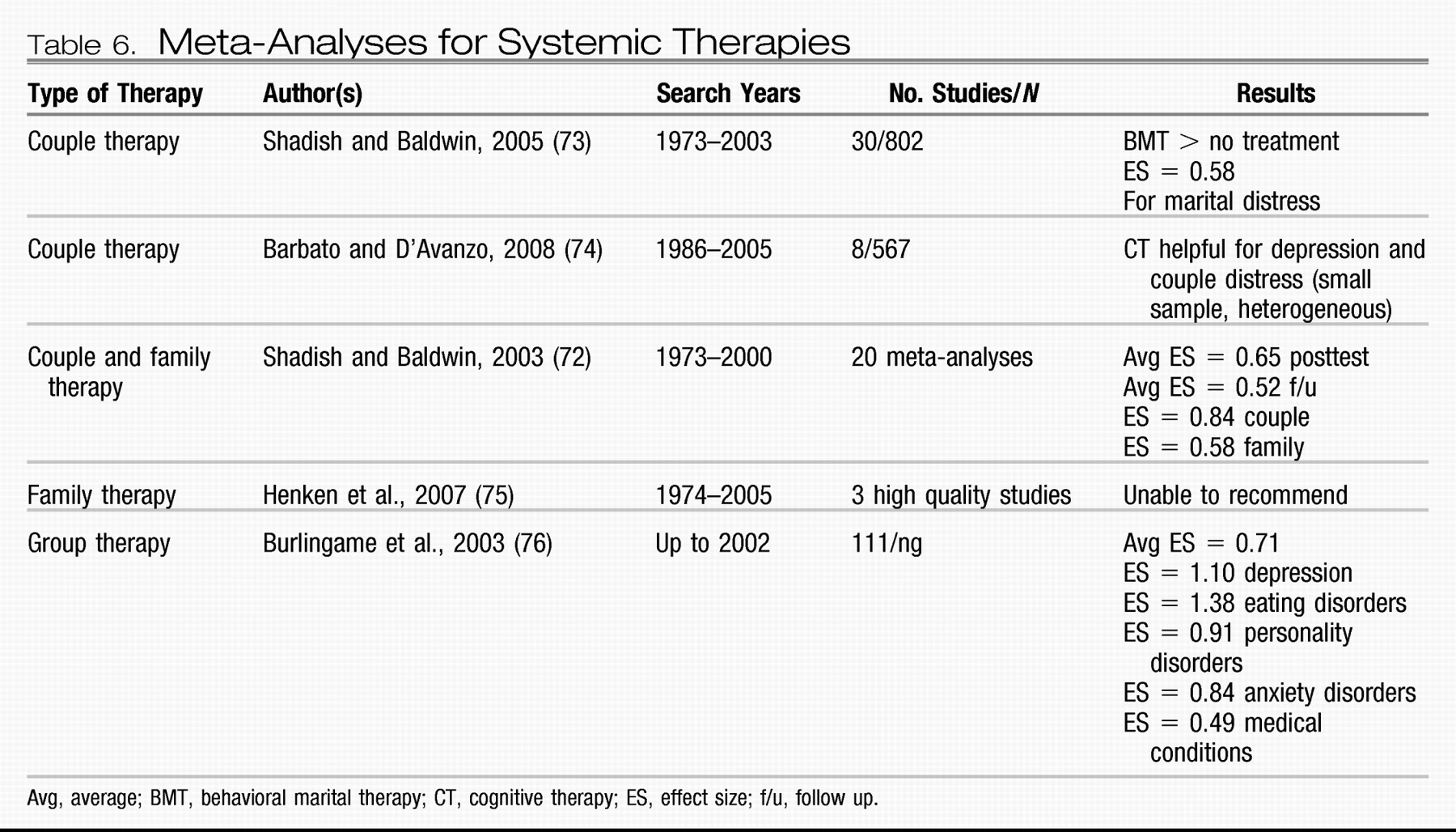

Systemic therapies have also been investigated for patients with psychiatric problems (

Table 6). There is strong support for couples therapy as an intervention for couples experiencing relationship distress, with large effect sizes being reported (

72). Behavioral marital therapy shows a moderate effect size in the treatment of marital distress (

73). Couples therapy has always demonstrated consistently higher effect sizes than family interventions, and this has been attributed to family problems being more intractable and involving more patients. Whether this explains the lower effect sizes seen in family therapy is unclear. Moderate effect sizes have been reported for family therapy as an adjunct in child and adult disorders and in specific family problems (

72,

74). However, one meta-analysis has indicated that, based on the few studies, recommendations at this time are difficult to make (

75).

Group interventions minimize the use of resources and offer patients additional benefits such as increased social support and the perception that there are others who struggle with the same illness. Moderate to large effect sizes support the use of many types of group-based interventions in the treatment of several psychiatric disorders (

76).

INDIVIDUAL VARIABLES AND DIFFERENTIAL TREATMENT OUTCOME

Although psychotherapies are effective treatments for many patients with psychiatric disorders, not all patients benefit from all treatments. There are probably many reasons for this outcome. First, there is great variability among therapists in their level of skill and expertise in delivering a specific treatment. Therapist competence is an important variable in outcome as it determines the integrity of treatment delivered (

77). Although most studies control for this factor, they tend to use novice therapists such as psychology graduate students or psychiatry residents who have yet to develop finely tuned skills in a particular form of therapy. Novice therapists are also known to have more difficulty with more severely ill patients, particularly those who are struggling with developing an alliance with their therapists.

Second, there may be diagnostic issues in that a patient may be receiving a treatment for an illness he or she does not have. For example, treating a patient with dysthymia with a brief course of CBT may not produce the best results (

66). Such patients require longer treatment and booster sessions after therapy. Third, there could be significant comorbidity that makes it difficult to focus on a target problem. As discussed above, patients with panic disorder and significant comorbidity have a poorer outcome than those who do not present with comorbidity (

48). These patients may require more careful integration of several types of treatment and longer duration of delivery of each treatment. For the practicing psychiatrist “real-world” patients present with extensive comorbidity, longer duration of illness, and prior failures to many forms of treatment. Rarely do patients present with one axis I diagnosis.

Fourth, the patient may be unable to form a therapeutic alliance with the therapist, essential for successful psychotherapy outcome regardless of treatment type. This important variable is discussed at length below. And finally there may be individual factors that are specific to the patient that make him or her unlikely to respond to one form of psychotherapy but more responsive to another. A similar analogy would be depressed patients' differential response to various antidepressants. For whatever reason, some patients may be suitable for one form of psychotherapy and not another, based on multiple factors. Some patients may be more action oriented, preferring homework and behavioral exercises, whereas others may be noncompliant in this area, preferring to talk about their issues and explore their feelings. Identifying these individual variables early may help us match the patient to the treatment and be more efficient in our outcomes.

To explore significant patient variables that predict psychotherapy outcome, PsycINFO and PubMed were searched for the past 20 years using the search terms “patient variables (factors),” “client variables (factors),” predictors,” and “psychotherapy outcome.” Thirteen articles and/or chapters discussing specific patient variables that predicted differential response to psychotherapy were identified. The earliest research identified the patient's readiness to change as a predictor of engagement and outcome in therapy. Four stages of readiness to change have been described, including precontemplative, contemplative, action, and maintenance, with the majority of patients being in the first two stages, either not ready or contemplating change (

78). MI assists in identifying the patient's stage and then helps prepare him or her for treatment (

79). Patients in the precontemplative and contemplative stages need time to explore the risks and benefits of choosing a course of treatment and benefit from exploratory interventions such as MI, experiential or psychodynamic therapy. Patients in the action stage are more receptive to therapy and are probably good candidates for a specific form of treatment requiring action such as CBT (which involves exposure, cognitive restructuring, and specific exercises) or IPT, which also involves some problem-solving techniques to increase social support (

80). Evidence to date indicates that this is an important variable, particularly in the treatment of addictive behaviors such as substance abuse (

80). Therefore, readiness to change has been found to be an important variable in determining

where to start with a patient. This may also encourage a better therapeutic alliance and increase the probability that a patient will remain in treatment. Additional treatments can be considered after patients have engaged in the initial treatment.

Other individual variables have been found to predict differential response to psychotherapy. Beutler et al. (

81) found that patient resistance and reactance level predicted specific responses to certain therapeutic approaches. Patients low on the resistance/reactance variable were described as accepting of interpretations, homework, direction, and authority and generally being open and nondefensive in treatment. These patients generally did well in most treatments. Patients high in resistance and reactance, however, were described as being more resistant to treatment suggestions such as interpretations and prescription of homework. These patients generally valued autonomy, were described as dominant, and had a history of poor response to previous treatment. Patients with this response style did better with nondirective, exploratory therapies, emphasizing self-change (psychodynamic and experiential) and also benefitted from paradoxical interventions if carried out by an expert therapist in a timely fashion (

82).

Degree of relatedness has also been found to predict differential response to treatment. Patients found to have a sociotropic style of relating (investment in long-term relationships) did well in supportive-expressive, long-term psychodynamic, and interpersonal therapy (

83), whereas those patients with an introjective/autonomous style (values independence and autonomy) did better with psychodynamic and cognitive behavior therapies (

83). Likewise, McBride et al. (

84) found that attachment styles predicted response to treatment with those insecurely attached responding preferentially to psychodynamic and interpersonal therapies and those avoidantly attached faring better with cognitive therapies. Similarly, personality variables have also been studied with respect to differential outcome to treatment in specific psychiatric disorders with avoidant patients responding better to CBT and obsessional patients faring better with IPT in the treatment of depression (

85). Patients with cluster B personality traits show a preferential response to those therapies that are highly structured and provide very clear, rigid boundaries (

86).

Other patient variables that have been explored include functional impairment, religion and spirituality, and gender matching. Research to date indicates that severely functionally impaired patients do well with medications first, followed by psychotherapy. However severity of illness does not preclude the use of psychotherapy, although one should proceed with the idea that more time and effort will be required to attain a good outcome. There is no evidence to suggest that matching the patient's religion or gender to those of the therapist is essential for a positive outcome in therapy unless this is specifically requested by the patient (

87).

Finally and perhaps new to the field is the contribution of neuroscience in predicting differential outcome to treatment. Imaging studies have shown that patients with OCD who show a decrease in pretreatment orbital-frontal cortical metabolism have a better response to medications, whereas those who show an increase have a better response to CBT (

88). Imaging studies have also shown that medications, CBT, and IPT, when effective, all reverse pretreatment abnormalities in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, the area identified in depression (

89). However, different regional effects were observed specific to each treatment. In an intriguing study, Goldapple et al. (

90) found that depressed patients who responded to CBT showed a decrease in glucose metabolism in the frontal and parietal regions but an increase in glucose metabolism in the hippocampal region, whereas those depressed patients who responded to paroxetine showed the reverse pattern. Although in its infancy, these studies offer the hope of isolating a neural signature in predicting differential outcome to treatment (

89), which is an exciting possibility for the future!

CONCLUSION

The last decade has witnessed an explosion of research in psychotherapy for patients with psychiatric disorders. As outlined above numerous meta-analyses (or level 1 evidence) have demonstrated moderate to large effect sizes for many forms of psychotherapy such as CBT, IPT, EFT, behavioral activation, DBT, exposure and response prevention, EMDR, STPP, and psychodynamic therapy for psychiatric patients across the lifespan, representing a significant shift in the literature from decades ago. Numerous psychotherapies have been studied for depression, whereas CBT has been studied mainly for patients suffering from anxiety disorders and other conditions. Despite these promising findings, it is well known that not all therapies help all patients. Recent efforts to identify patient variables that can be matched to specific treatments have pointed to personality variables, attachment styles, and patient reactance and resistance in treatment. Although preliminary, it is intriguing to consider various individual variables when one is making treatment decisions.

Although specific therapies for specific disorders and individual variables that predict differential response to treatment dominate the literature, the therapeutic alliance formed between the patient and the psychiatrist continues to be a robust indicator of treatment outcome, indicating yet again that without a sound therapeutic relationship one cannot engage in any form of psychotherapy or other form of treatment with any success at any time. Although this information is well known to the practicing psychiatrist, it is important to know that it is supported by at least three decades of empirical research.

In summary, as clinical psychiatrists we frequently see patients struggle through a particular form of psychotherapy, unable to move forward and unable to use the sessions as we had hoped. This failure may not always be resistance, defense, transference, or homework noncompliance. In such cases it is important to consider several factors:

1.

What is the patient's diagnosis or problem?

2.

Are you delivering an evidence-based treatment specific for that diagnosis or problem?

3.

Are there patient variables that might suggest an alternate treatment?

4.

Are there therapeutic alliance issues?

These are critical questions to consider, for the ultimate goal of treatment is to efficiently help patients recover and experience improvement in overall symptoms and general functioning.

Since the last issue of Focus dedicated to psychotherapy, much has changed. There have been numerous RCTs for several different psychotherapies, with more than 60 meta-analyses in the past decade alone. Several new psychotherapies have been identified for patients with psychiatric disorders and unique patient characteristics have been investigated to help match patients to specific treatments. Neuroscience also offers exciting possibilities of predicting differential response to treatment. In addition, as already established, the therapeutic relationship continues to be a robust predictor of outcome.

I look forward to the next issue of Focus dedicated to psychotherapy. One wonders what new discoveries will be made by then. It is hoped that empirical research will continue to support new therapies for patients with psychiatric disorders, identify additional patient variables that predict differential response to treatment, and explore therapist variables important in how we deliver psychotherapy, so that we can be more competent general psychiatrists and psychotherapists. Research aimed in this direction will continue to promote the evidence-based practice of psychotherapy and benefit patients struggling with complex psychiatric problems.