INTRODUCTION

Genetic variability in dopamine transmission may influence the temperament dimension of novelty seeking (NS) (

Cloninger et al., 1993). In accordance with this hypothesis, a polymorphism in the dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4) exon III has been identified that may be associated with NS. Some empirical evidence shows that long alleles, mostly representing the seven-repeat, are associated with higher NS scores (

Benjamin et al., 1996,

2000;

Ebstein et al., 1996,

1997;

Noble et al., 1998;

Strobel et al., 1999;

Tomitaka et al., 1999). Evidence also exists that the seven-repeat allele is associated with lower NS scores in substance abusers (

Malhotra et al., 1996;

Gelernter et al., 1997), and that the DRD4 polymorphism and NS are not associated (

Malhotra et al., 1996;

Gelernter et al., 1997;

Ono et al., 1997;

Sander et al., 1997;

Pogue-Geile et al., 1998;

Sullivan et al., 1998;

Bau et al., 1999;

Kuhn et al., 1999;

Comings et al., 2000;

Gebhardt et al., 2000;

Herbst et al., 2000;

Mitsuyasu et al., 2001;

Soyka et al., 2002). Moreover, two- or five-repeat alleles were shown to contribute to higher NS scores in two independent Finnish samples (

Ekelund et al., 1999;

Keltikangas-Järvinen et al., 2003).

Recent meta-analyses (

Kluger et al., 2002;

Schinka et al., 2002) showed that the divergence among the studies does not appear random, but is likely to reflect true heterogeneity between the studies, indicating that there are unknown moderators in the association between the DRD4 polymorphisms and NS, such as environmental factors (

Bouchard, 1994;

Plomin et al., 1994). We have recently demonstrated that the association between the DRD4 polymorphism and NS in adulthood was moderated by the early childhood rearing environment (

Keltikangas-Järvinen et al., 2004), such that when the rearing environment was more negatively tuned, the two- or five-repeat alleles were more common in a group scoring high on NS, and when the rearing environment was less negatively tuned, the genotype and NS were not significantly associated. Negatively tuned childhood environment was characterized as mother-reported emotional distance, low tolerance towards the child's normal activity, and a strict disciplinary style.

A specific potential moderator of the association between the DRD4 polymorphism and NS may be parental alcohol consumption. Parental alcoholism and/or alcohol use may predict high NS in the offspring (

Sher et al., 1991;

Ravaja and Keltikangas-Järvinen, 2001), and may increase the risk of early onset alcohol use in the offspring (

Webb and Baer, 1995); NS, in turn, has been shown to predict early onset alcohol abuse (

Cloninger et al., 1988). A recent study showed that adolescent sons of alcoholic fathers exhibited significantly higher extraversion scores—a personality trait closely correlated with NS temperament (

Zuckman and Cloninger, 1996) —than sons of nonalcoholics, if they carried the minor alleles of the DRD2 gene, whereas the father's alcoholism did not affect the DRD4 seven-repeat and extraversion association (

Ozkaragoz and Noble, 2000). Finally, some of the previous studies have identified that the seven-repeat allele of the DRD4 polymorphism is associated with low NS scores in substance-abusing subgroups (

Malhotra et al., 1996;

Gelernter et al., 1997).

Our aim in the current study was to find out whether interactions between parental alcohol use during the childhood/adolescence of their offspring and DRD4 polymorphism predicted NS temperament in adulthood over 17 years. In addition to focusing on two- or five-repeat alleles of the DRD4 gene, which have been shown to contribute to higher NS scores in the current sample (

Keltikangas-Järvinen et al., 2003) and another independent Finnish sample (

Ekelund et al., 1999), we tested whether the parental alcohol consumption moderated any potential associations of the seven-repeat allele of the DRD4 gene and NS.

RESULTS

The distribution of the DRD4 alleles was comparable with the results of previous studies (

Ekelund et al., 1999;

Herbst et al., 2000). Frequencies of 8.3, 7.7, 63.7, 4.3, 0, 15.7 and 0.4% were found for alleles 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, respectively. The distribution of the DRD4 genotypes were as follows: 37.3% of the participants carried the 4/4 genotype, 25.3% the 7/4 genotype, 12.0% the 4/3 genotype, 10.7% the 4/2 genotype, 4.0% the 5/4 genotype, 2.0% the 3/2, 7/2, or 7/5 genotype, and 0.7% the 2/2, 5/2, 5/3, 5/5, 7/3, 7/7, or 8/4 genotype. When the participants were pooled on the basis of the DRD4 alleles, 23.3% carried any and 76.7% carried no two- or five-repeat alleles, whereas 30.7% carried any, and 69.3% carried no seven-repeat alleles.

More fathers than mothers belonged to the group of more frequent alcohol consumption and drunkenness. In 1980, 60.9% of the fathers versus 39.1% of the mothers belonged to the more-frequent-consumption group (P < 0.001), and in 1983, the respective figures were 59.8 and 38.5% (P < 0.001). Similarly, in 1980, 43.2% of the fathers versus 16.7% of the mothers belonged to the more-frequent-drunkenness group (P < 0.001), whereas in 1983, the respective figures were 42.3 versus 18.7% (P < 0.001).

Parental alcohol use was highly stable over the examinations in 1980 and 1983. Of the fathers belonging to the more-frequent-consumption group in 1980, 88.9% belonged to the more-frequent-consumption group in 1983, and 82.0% of the fathers belonging to the less-frequent-consumption group in 1980, belonged to the same group in 1983 (κ = 0.71, approx t = 7.9, P < 0.001); 83.7% of the fathers reported consistently more and 84.7% consistently less frequent drunkenness in 1980 and 1983 (κ = 0.68, approx t = 7.5, P < 0.001). Of the mothers, 80.0% reported consuming alcohol consistently more and 83.1% consistently less frequently in 1980 and 1983 (κ = 0.63, approx t = 7.4, P < 0.001), and 70.8% reported consistently more and 89.6% consistently less frequent drunkenness in 1980 and 1983 (κ = 0.56, approx t = 6.6, P < 0.001).

As previously reported by

Keltikangas-Järvinen et al. (2003), the participants carrying any two- or five-repeat alleles of the DRD4 gene had a significantly greater risk of exhibiting NS scores that were above the 90th percentile on a population distribution than those carrying none (odds ratio = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.11–5.20).

Reports of parental alcohol use in 1980 showed that more frequent experiences of feeling drunk by the mothers (χ

2 = 6.9; df = 1;

P < 0.01) and the fathers (χ

2 = 7.4; df = 1;

P < 0.01) were associated with higher NS scores in the offspring 17 years later (cf.

Ravaja and Keltikangas-Järvinen, 2001).

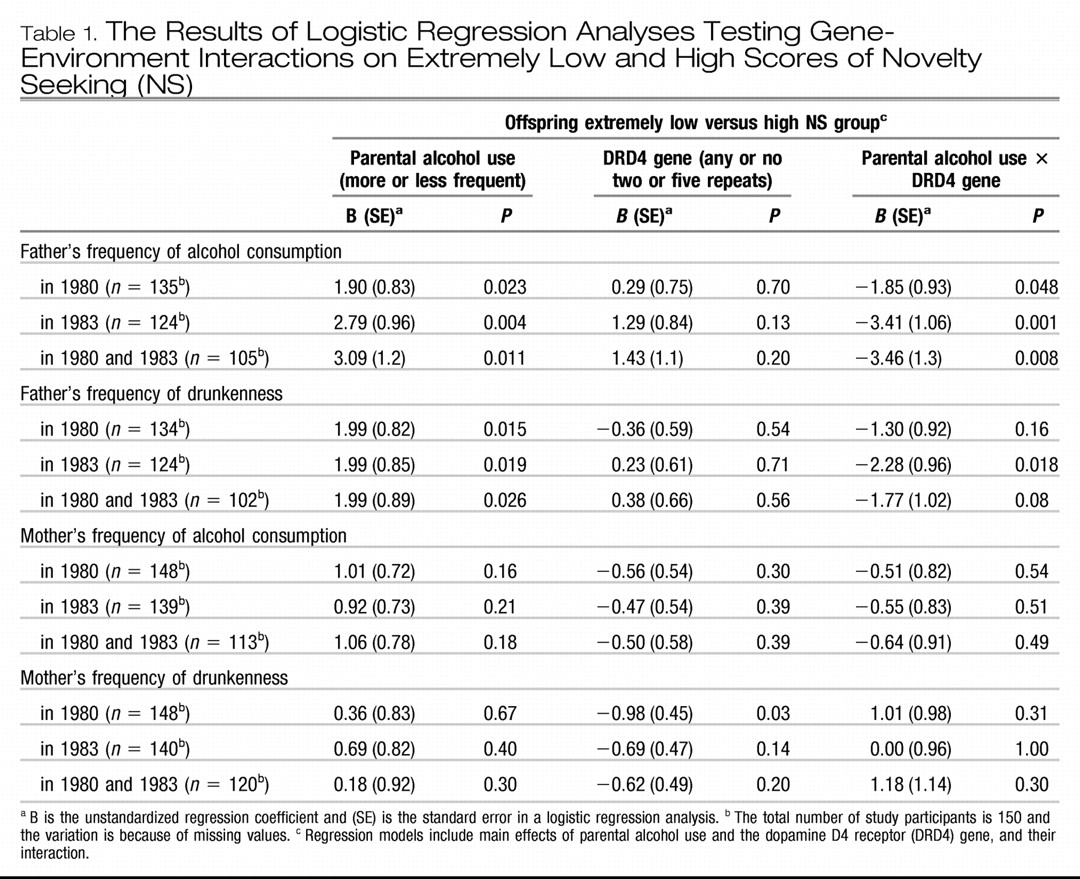

Table 1 shows the results of the logistic regression analyses testing gene-environment interaction on NS. Paternal alcohol consumption moderated the association between the DRD4 polymorphism and NS in the offspring. When the father reported more frequent consumption of alcohol in 1980 (odds ratio = 4.76, 95% CI = 1.61–14.08), in 1983 (odds ratio = 8.33, 95% CI = 2.36–29.38), and at both points in time (odds ratio = 7.62, 95% CI = 2.06–28.18), the participants carrying any versus no two- or five-repeat alleles had a significantly greater risk of belonging to the group scoring above the 90th percentile on the population distribution of NS (extremely high NS). When the father reported consuming alcohol less frequently, the allelic diversity of the DRD4 gene had no effect on NS (all

P-values > 0.17).

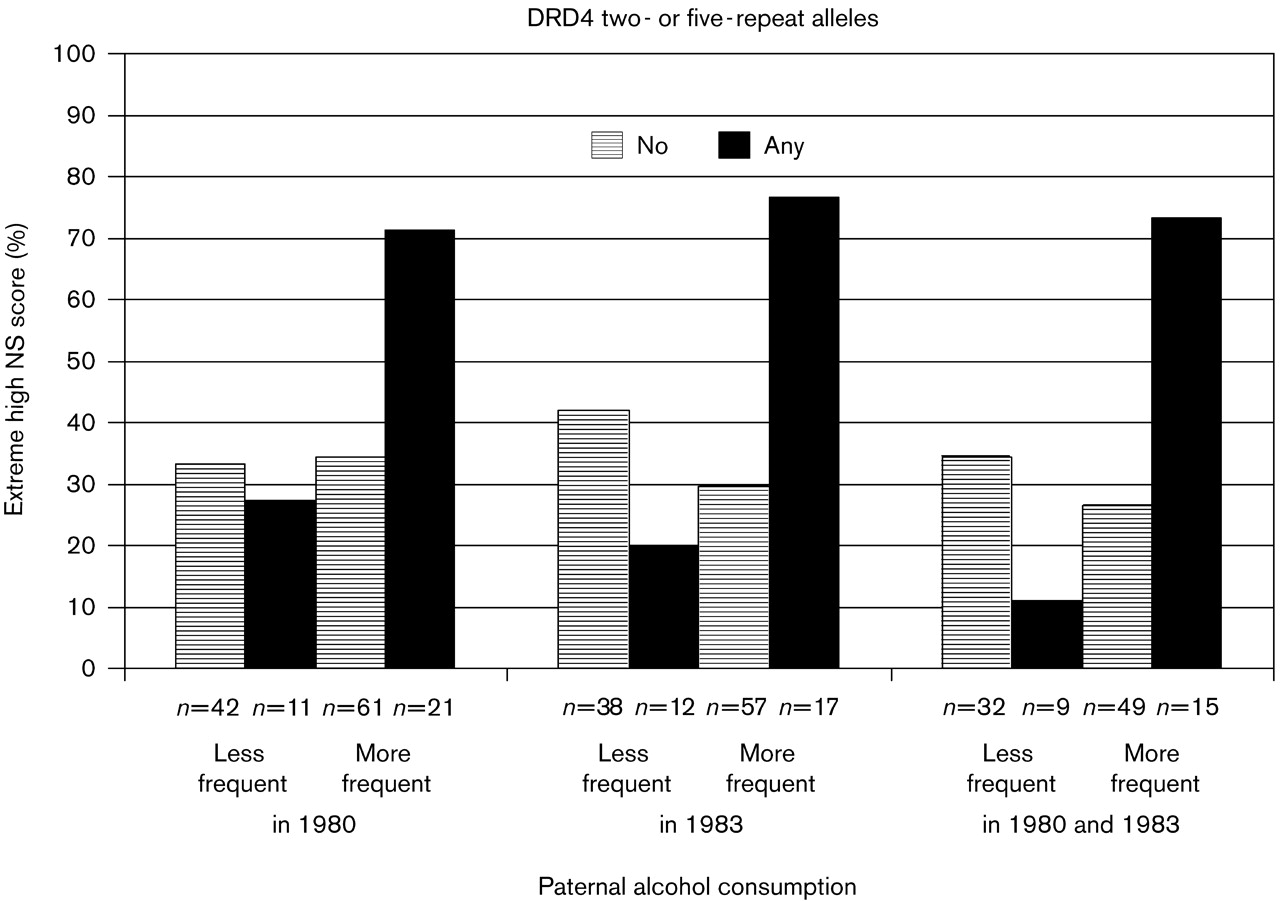

Figure 1 shows the proportion of participants belonging to the 90th percentile group on NS according to DRD4 two- or five-repeat allele status and frequency of paternal alcohol consumption. When we controlled for the main effect of maternal child-rearing, and the moderation effect of DRD4 by child-rearing, the associations remained significant (all

P-values < 0.04) with one exception: the moderation effect of DRD4 by paternal alcohol consumption in 1980 became non-significant (

P-values > 0.06).

Further, when the father reported feeling drunk more frequently in 1983, the participants with any versus no two- or five-repeat alleles had a significantly greater risk of belonging to the group scoring above the 90 percentile (extreme high NS) on the population distribution of NS (odds ratio = 7.78, 95% CI = 1.81–33.38; 10 out of 13 participants for any two or five repeats of the DRD4 gene belonged to extremely high NS group versus 12 out of 40 participants for no repeat). When the father reported less frequent drunkenness, the offspring DRD4 alleles had no effect on NS (all P-values > 0.56). This moderation effect became non-significant when the main effect of maternal child-rearing, and the moderation effect of DRD4 by maternal child-rearing were controlled for (P-values > 0.056).

Maternal alcohol consumption did not moderate the association between the DRD4 two- or five-repeat alleles and NS (all P-values > 0.30). Parental alcohol consumption did not interact with the DRD4 seven-repeat allele in the analysis of NS (all P-values > 0.13). Statistical controls for age and sex did not alter the significant associations.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we tested whether parental alcohol use during the childhood/adolescence of their offspring moderated the effect of the DRD4 polymorphism on NS temperament over 17 years. The results showed that when the father, but not the mother, reported more frequent alcohol consumption (daily to a couple of times a month) or drunkenness (daily to every second month) 17 and/or 14 years before the assessment of NS, the offspring carrying two- or five-repeat alleles of the DRD4 gene had a 4.76–8.33 times greater risk of belonging to the extremely high NS group than those carrying other alleles of the same gene. The genotype had no effect on NS when the father reported less frequent alcohol consumption or drunkenness. Maternal alcohol consumption did not moderate any of the associations. Nor did we find any associations between parental alcohol consumption, the seven-repeat variant of the DRD4 gene and NS temperament.

Ozkaragoz and Noble (2000) recently demonstrated that adolescent sons of alcoholic fathers carrying the minor alleles (A1+, B1+, 1+) of the DRD2 gene, showed significantly higher extraversion scores than the sons of non-alcoholic fathers. Given these findings, they proposed that individuals with minor alleles of the DRD2 gene might cope with a stressor (i.e. the consequences of paternal alcoholism) by increasing their level of activity while children with major alleles of the DRD2 gene would decrease their activity.

Berman et al. (2002) hypothesized that the developmental mechanism of NS in combination with the DRD2 minor allele (A1+) is based on negative reinforcement or self-medication, whereas the DRD2 major allele (A1−) is associated with NS based on positive reinforcement or the fulfillment of appetitive drives. Even though DRD2 and DRD4 belong to the same family of dopamine receptors, direct comparisons between the results involving the DRD2 and DRD4 genes cannot be made. However, it could be asked to what extent the current findings reflect differences in reaction to chronic environmental stress according to the DRD4 variant. Parental alcoholism has been associated with increased stress in the offspring (

Reich et al., 1988;

Roosa et al., 1988). Individuals with DRD4 two- or five-repeat alleles may cope with that stress by increasing their level of activity, which becomes manifested as NS temperament. This is consistent with findings on DRD4 receptor knockout mice, suggesting that one function of the dopamine receptor D4 is to regulate anxiety and stress reactions (

Falzone et al., 2002).

Another potential explanation for the current findings is that there may exist an unknown common underlying factor that exerts effects on both the father and the offspring. This factor may be either another gene polymorphism, resulting in epistasis with the DRD4 gene, or other environmental or demographic factors.

We have recently demonstrated that a negatively tuned maternal rearing environment moderated the association between the DRD4 two- and five-repeat alleles and NS (

Keltikangas-Järvinen et al., 2004). The current finding adds to our previous result by showing that there may be multiple, partly overlapping and partly independent, environmental moderators that may have complex associations with each other. Controlling for the rearing environment diminished the moderating effects of paternal drunkenness, but did not have a significant effect on the moderating effects of the frequency of paternal alcohol consumption. This suggests that a negatively tuned rearing environment partly overlaps with parental alcohol use, but that paternal alcohol consumption also has a significant independent role as a moderator.

To our knowledge, no studies have found environmental moderators of the association between the DRD4 seven-repeat allele and NS. This is indeed important, because there may be two developmentally different NS phenotypes, as suggested by

Berman et al. (2002), with different genetic backgrounds and environmental moderators.

In future studies, questions regarding the possible passive gene-environment correlation between the DRD4 gene, parental alcohol use, and NS need to be addressed. Because parental genotype determines offspring genotype fully and the environment in which the child develops partially, parental genes (e.g. the DRD4 gene) could be responsible for both parental alcohol use and offspring NS. Consequently,

Enoch et al. (2003) have suggested that NS might have a role as an intermediate phenotype in the search for the genetics of alcoholism. However, studies connecting DRD4 and alcoholism have failed to find an association (cf. review by

Dick and Foroud, 2003).

One limitation of the present study is the small sample size. However, the participants who scored above the 90th percentile and below the 10th percentile on NS were selected for the current study from a population sample of 2149 participants. The population sample decreases the possibility of distortions in associations between the variables (

Cohen and Cohen, 1984), and selective genotyping was shown to increase the statistical power per genotype fivefold compared with random genotyping, provided that the number of individuals phenotyped is increased fourfold (

Darvasi and Soller, 1992). Because of the small sample size, testing the effects separately by birth cohort and sex remains a future study question. Another limitation is the non-standardized assessment of parental alcohol consumption. However, questions regarding frequency of consumption and heavy drinking are typical in epidemiological studies because they provide the necessary variance in population-based samples. The under-reporting of alcohol use by parents also remains a possibility because of the social undesirability of this behaviour. However, parental alcohol consumption was measured at two points in time. The measures showed high individual stability, and the findings on the moderating role of parental alcohol consumption were highly comparable in the two examinations conducted 3 years apart.

We have taken into consideration the points made by

Lusher et al. (2001), who recently suggested that studies on DRD4 and NS associations should comprise participants under 45 years of age, should utilize personality scales with high reliability and validity such as the Temperament and Character Inventory, should study the effects in a homogenous sample according to ethnicity, and should consider the effects of sex on the results.

To our knowledge, this study is one of the very few to have tested gene-environment interaction in the context of a specific personality trait, and to have utilized a prospective design extending over different developmental stages. The findings underline the importance of taking both nature and nurture into consideration when trying to form a clear picture of genetic bases of complex human behavioural patterns.