1. Introduction

Converging lines of evidence suggests the importance of sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder (e.g.,

Ehlers et al., 1988;

Harvey, 2009). Sleep disturbance is an important symptom of bipolar disorder across mood phases. During manic episodes, there is a reduced need for sleep, whereas episodes of depression in bipolar disorder are characterized by either insomnia or hypersomnia (

American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Sleep is also impaired in bipolar disorder even when patients are not actively symptomatic. In fact, 70% of euthymic bipolar patients report clinically significant levels of sleep disturbance (

Harvey et al., 2005). Cross-sectional research suggests that both short (<6 h) and long (≥9 h) sleep durations are associated with impaired functioning and quality of life in bipolar disorder (

Gruber et al., 2009).

There is evidence that sleep disturbance may be causally related to recurrence. Disturbance in sleep is a common prodrome of both manic and depressive episodes (

Jackson et al., 2003). Experimentally-induced sleep deprivation has been associated with a worsening of both depressive and manic symptom severity the subsequent day in patients with bipolar disorder in some studies (e.g.,

Colombo et al., 1999;

Kasper and Wehr, 1992;

Wu and Bunney, 1990), but with improvement in others (e.g.,

Barbini et al., 1998). Few studies, however, have prospectively monitored sleep quality and mood episode status. One study found that shorter sleep duration predicted greater depressive, but not manic, symptoms over 6 months in patients with bipolar I disorder (

Perlman et al., 2006).

Barbini et al. (1996) monitored 34 patients with mania over three days for sleep duration and manic symptoms and found significant correlations between decreased sleep duration and increased manic symptoms the subsequent day. Finally,

Bauer et al. (2006) recorded patterns of mood, sleep and bedrest over a minimum of 100 (

M = 169,

SD = 59) days in 59 inpatients that were currently manic. They found that a decrease in sleep or bedrest was followed by a shift towards hypomania/mania on the next day, whereas an increase in sleep or bedrest was followed by a shift towards depression the next day. Taken together, these studies find longitudinal associations between sleep disturbance and mood changes in bipolar disorder, although the nature of the association— whether sleep disturbance is more related to manic or depressive symptoms—is less consistent.

The current study addressed two aims. The first was to examine whether there was an association between sleep functioning and mood symptoms in recovered (i.e., euthymic) patients with bipolar disorder upon study entry into the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), a multi-site longitudinal study. Prior cross-sectional and experimental evidence suggests that shortened total sleep duration is associated with increased depressive and manic symptom severity (e.g.,

Bauer et al., 2006;

Colombo et al., 1999;

Kasper and Wehr, 1992;

Perlman et al., 2006;

Wu and Bunney, 1990) as well as impaired functioning (e.g.,

Gruber et al., 2009). This aim focused on whether such associations are observable in a remitted bipolar sample. We hypothesized that lower Total Sleep Time (TST) and greater Sleep Variability (SV) would be associated with increased symptom severity and decreased functioning at study entry.

The second aim was to investigate whether there is an association between sleep functioning with symptom severity and functioning across a 12-month prospective period. This association has not been investigated in patients who are minimally symptomatic (no more than two threshold mood symptoms) at study entry. Our second hypothesis was that greater SV would be associated with increased mania severity, increased depression severity, and decreased global functioning. This hypothesis is based upon the supposition that irregularities in social rhythms, one of which includes sleep, is associated with increased risk for mania and depression symptom severity as well as poorer treatment outcome (e.g.,

Frank et al., 2005;

Goldstein et al., 2008).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

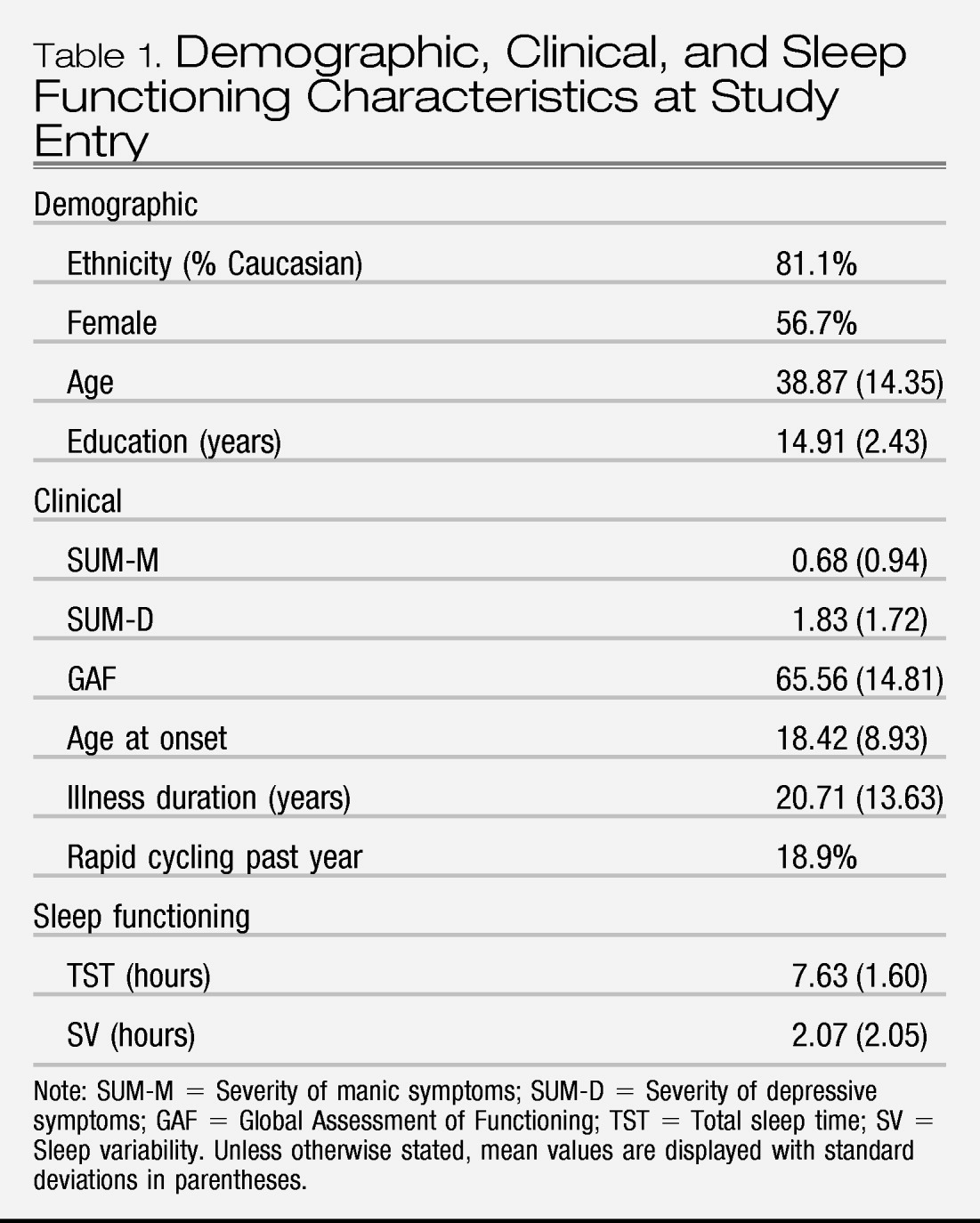

Demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in

Table 1. We first examined skewness and kurtosis indices of our primary independent variables (TST and SV). Given that both variables mirrored a normal distribution, we did not transform variables. Second, we examined whether demographic variables (gender, age, ethnicity, and education) were associated with TST or SV at baseline. Gender, education, and ethnicity were not associated with TST or SV (

ps >.05). Age was weakly but significantly negatively correlated with TST,

r (179) = −0.18,

p<.05, suggesting that older patients slept fewer hours than younger patients. Third, TST was negatively correlated with illness duration,

r(175) = −0.24,

p<.01, and SV was negatively correlated with age at onset,

r(459) = −0.11,

p<.05, suggesting that patients with earlier ages at onset and longer illness durations slept less and with more variability.

3.2. Concurrent associations between sleep with symptom severity and functioning

We conducted bivariate correlations between SV at baseline with mania severity (SUM-M), depressive symptom severity (SUM-D), and global functioning (GAF) at baseline. Given the significant correlation between TST and age, partial correlations between TST and SUM-M, SUM-D, and GAF at baseline were conducted including age as a covariate. Lower TST was associated with increased mania severity scores (r = −0.31) and greater SV was associated with increased mania (r = 0.18) and depression (r = 0.14) severity scores (ps <.01). Neither TST nor SV was associated with global functioning (r = −0.12 and −0.08, respectively).

3.3. Prospective associations between sleep with symptom severity and functioning

Mixed-effects regression models examined the relation of sleep disturbance (TST and SV) to symptom severity (SUM-D and SUM-M) or role functioning scores (GAF) during the same interval longitudinally across the 12-month period. All analyses controlled for the patient's age and number of psychiatric visits. The regression models conducted using PROC MIXED in SAS (

Littell et al., 1996) considered multiple follow-up visits simultaneously and missing data was excluded listwise. Unlike standard repeated measures analyses of variance, mixed effects models with random subject effects permit the analysis of repeated measurements while controlling for the within-subject correlation of the dependent measure (e.g., SUM-D, SUM-M, or GAF). These methods assume that data are missing at random. Below is a model representation of our analytic procedure with the time-varying covariate, whereby a significant coefficient denotes a significant association between TST (or SV) and one of our three dependent measures (e.g., SUM-D, SUM-M, or GAF).

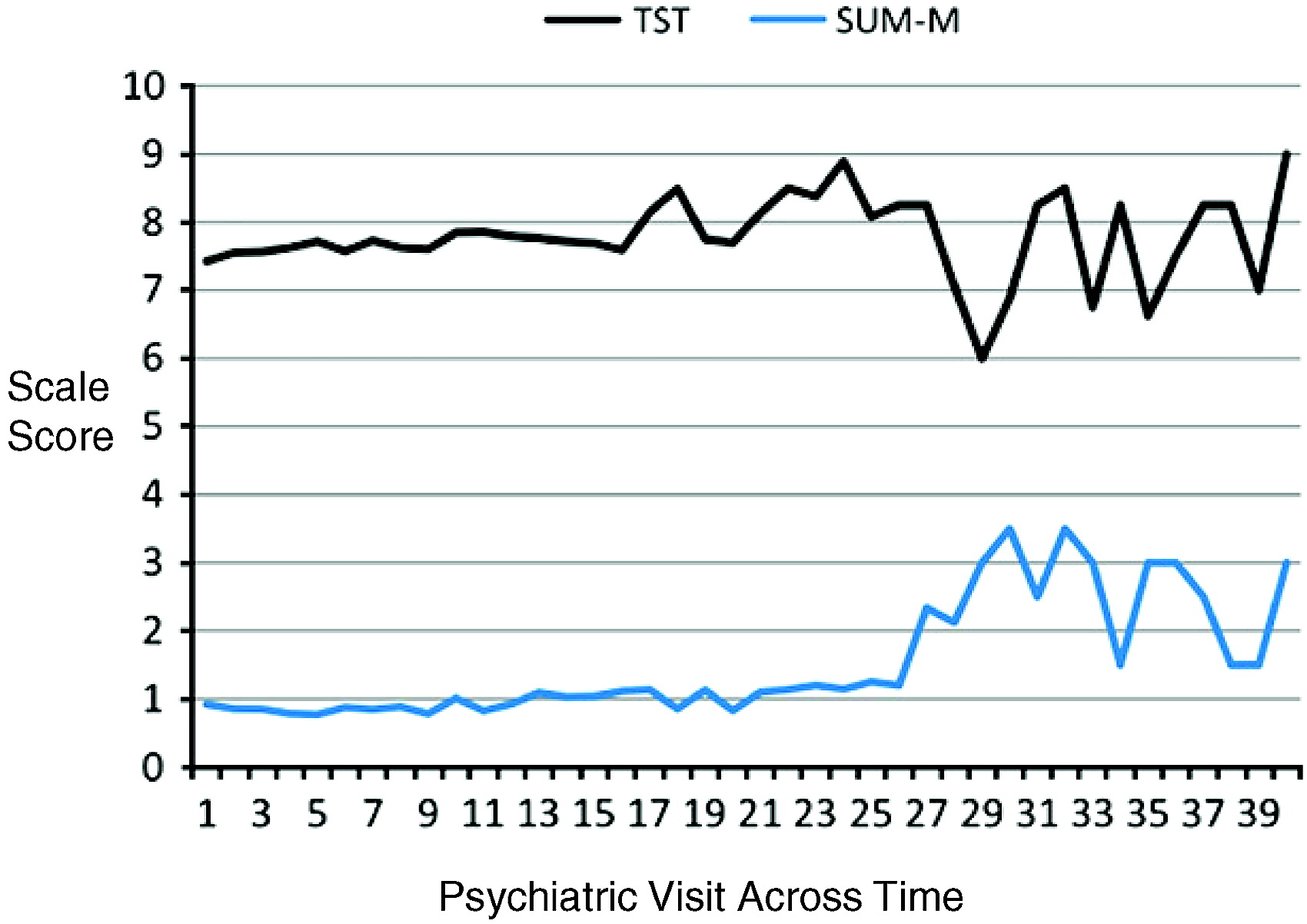

For symptom severity, results from the mixed-effects linear modeling across the 12-month period demonstrated that, over time, lower TST was associated with higher SUM-M scores [

F(1, 1397) = 71.46,

p<.0001] (see

Fig. 1). TST was unrelated over time to SUM-D scores [

F(1, 1384) = 3.18,

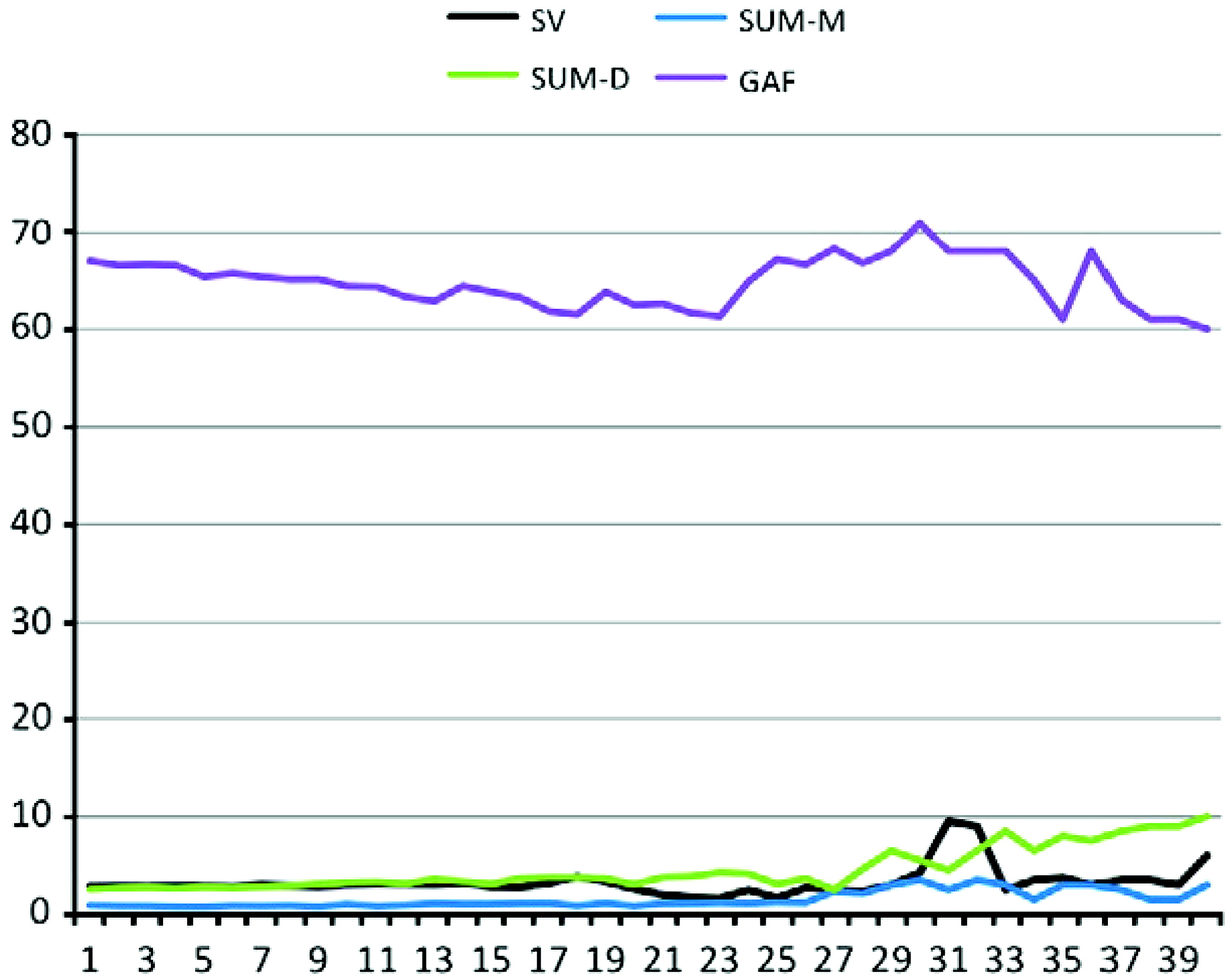

p = 0.07]. Moreover, mixed-effects linear modeling demonstrated that increases in SV over time were associated with increases in SUM-D [

F(1, 1393) = 31.39,

p <.001] and SUM-M [

F(1, 1360) = 10.03,

p < .01] scores (see

Fig. 2).

For global functioning, mixed-effects linear modeling did not demonstrate a relationship over time between TST and GAF scores [F(1, 1313) = 0.72, p = .40]. Increases in SV over time were associated with increases in GAF scores [F(1, 1330) = 7.99, p < .01], although this association was no longer significant once SUM-M and SUM-D scores were covaried [F(1, 1268) = 0.34, p>.10].

4. Discussion

For some time sleep disturbance has been implicated as important in bipolar disorder (e.g.,

Ehlers et al., 1988) and evidence now supports these claims (e.g.,

Harvey, 2009). Few studies have prospectively examined the relationships of sleep with symptoms and functioning, especially in a larger sized bipolar cohort. Our results revealed significant concurrent and prospective associations between SV and TST with both mood symptoms and functioning in bipolar disorder.

We note that the results of the present study need to be interpreted within the confines of several limitations. First, the existing sleep variables in the STEP-BD database were limited in several ways. Specifically, measures of sleep functioning from the CMF were measured using single score estimates of the maximum and minimum sleep averaged across the previous week, unlikely to fully reflect the central tendency of sleep patterns and variability in over this time period. For example, estimates of both SV and TST might be susceptible to retrospective memory biases as compared to daily sleep diaries, actigraphy, and polysomnography. Furthermore, it was not possible to make formal diagnoses of insomnia or hypersomnia based on the CMF and so future work is needed to replicate these findings when formal insomnia and hypersomnia diagnoses are made. Second, our measure of global functioning may not have been sensitive enough to capture sleep-related impairment Third, the medication regimens of patients were variable and changed over the 12-month follow-up period. Research indicates that frequently prescribed medications for bipolar disorder may influence sleep architecture (e.g.,

Eidelman et al., 2010). Future studies should systematically assess medication influences on leep duration and variability.

Considering these limitations, the present study represents a step forward in examining sleep functioning in bipolar disorder. More specifically, our first aim examined concurrent associations between sleep at study entry (i.e., baseline) with mood symptoms and functioning. Interestingly, lower TST was associated with more severe mania symptoms, whereas greater SV was associated with more severe mania and depression symptoms. Taking TST first, this finding is consistent with research documenting cross-sectional associations between short sleep durations and increased mania or hypomania (

Bauer et al., 2006;

Colombo et al., 1999;

Gruber et al., 2009;

Kasper and Wehr, 1992;

Wehr et al., 1987). For SV, the results suggest that greater variability in sleep may be associated with more severe mood symptoms. These findings are broadly consistent with the finding that disruptions in social rhythms, including sleep, are associated with greater depressive symptomatology in adolescents (

Goldstein et al., 2008). Moreover, disrupted social rhythms have been associated with increased risk for manic and depressive symptom severity and poorer treatment outcome (

Frank et al., 2005).

Our second aim examined prospective associations between sleep functioning with mood symptoms and functioning across a 12-month period using mixed-effects modeling. Consistent with concurrent associations at baseline, TST was associated with increased mania severity though TST was not associated with depression severity over time. This is inconsistent with the notion that extended sleep duration, or hypersomnia, is associated with greater symptoms of depression (

Kaplan and Harvey, 2009). However, the relationship is likely more complicated, given that depression can be characterized by either insomnia or hypersomnia (

American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Increased sleep variability was associated with greater manic and depressive symptom severity across the 12-month period. These results are consistent concurrent associations between SV and mood symptoms in prior work (e.g.,

Perlman et al., 2006). A tendency towards an inconsistent sleep pattern in bipolar disorder may precipitate the onset of mood episodes. Alternatively, prodromal mood symptoms may aggravate sleep regularity leading to the exacerbation of mood symptoms. A third possibility is that a bi-directional escalating vicious cycle is operating whereby sleep and mood progressively feed into the other worsening (

Wehr et al., 1987). Either way, there is likely to be value in exploring specific sleep variables in future research.

In sum, the present study suggests that longer total sleep duration was associated with more severe concurrent and prospective mania, but not depression, symptom severity in bipolar disorder. Furthermore, greater variability in sleep was associated with worsened concurrent and prospective mania and depression symptom profiles. No associations between sleep duration or variability emerged with global functioning. The present findings represent an important initial step towards identifying aspects of sleep functioning that may contribute to clinical impairment in bipolar disorder. Furthermore, this research underscores the importance of incorporating interventions that target sleep functioning aimed at promoting illness stabilization.