Diagnosis of bipolar depression

The diagnostic criteria, both in DSM-IV (

American Psychiatric Association 1994) and ICD-10 (

World Health Organization 1992), for a major depressive episode (MDE) as part of bipolar disorder are not different from those for MDE in unipolar depression. Some symptoms as leaden paralysis, hypersomnia or increased appetite have been reported to be more frequent in bipolar depression (

Akiskal et al. 1983;

Mitchell and Malhi 2004;

Perlis et al. 2006;

Goodwin and Jamison 2007). Other variables such as earlier onset of illness or family history of bipolar disorder may point towards an underlying bipolar course (

Winokur et al. 1993), and also some biological variables may show subtle differences (

Yatham et al. 1997). Looking at differing symptomatology in two large study cohorts of unipolar and bipolar depressed patients,

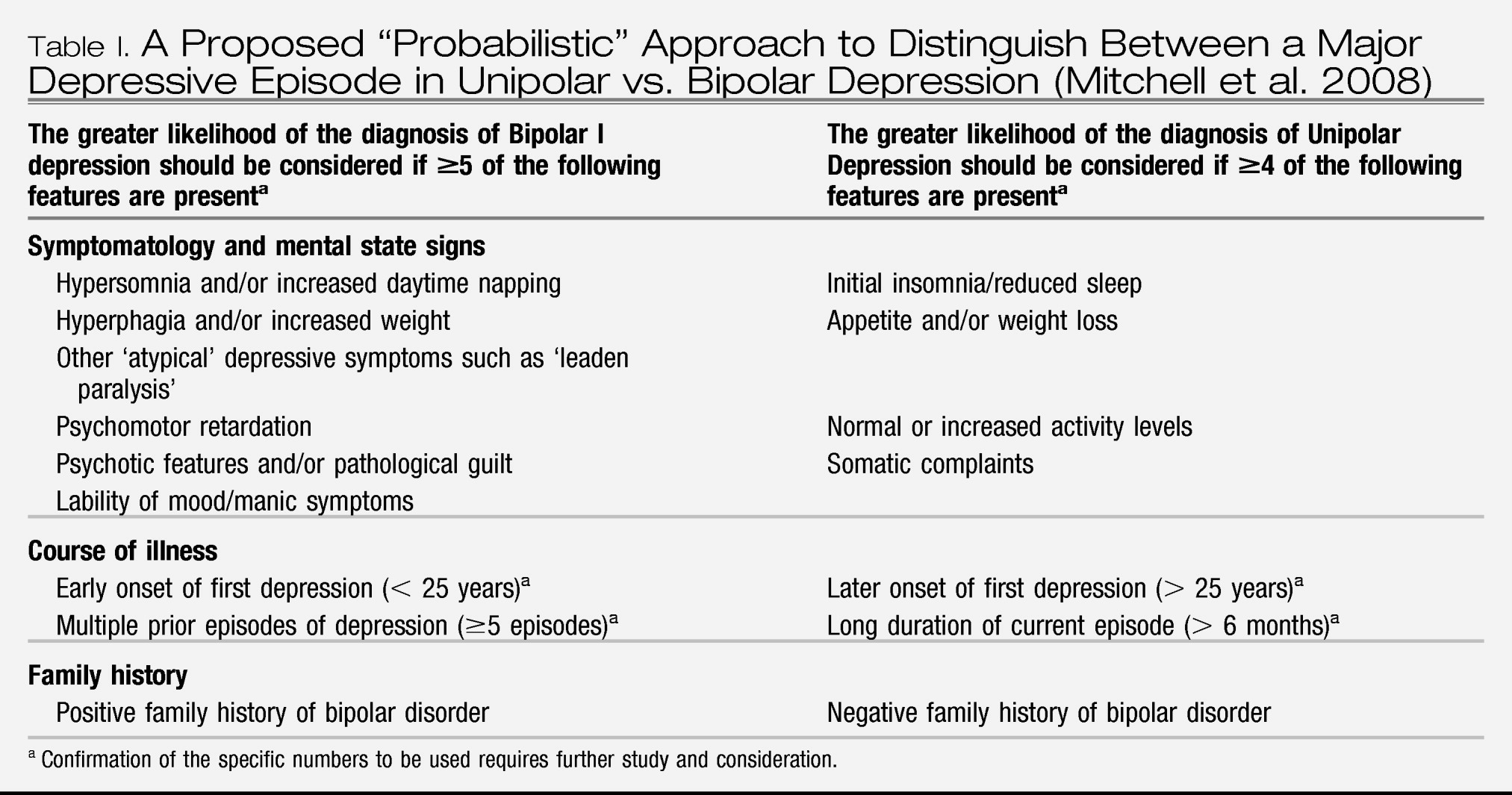

Perlis et al. (2006) identified eight individual symptom items on the Montgomery-Äsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale: inner tension, pessimistic thoughts, suicidal thoughts and fear were more frequent symptoms in bipolar subjects, whereas apparent sadness, reduced sleep and cognitive and several somatic symptoms of anxiety were more frequent in unipolars. A proposed “probabilistic” approach to distinguish between unipolar and bipolar depression in a person with a major depressive episode and no clear prior manic, hypomanic or mixed episode had been put forward by the International Society of Bipolar Disorder Guidelines Taskforce on Bipolar Depression, summarizing the so far available evidence (

Table I;

Mitchell et al. 2008). However, the presence or absence of any of these characteristics would not contribute to diagnostic certainty in the individual case. In addition, a substantial proportion of patients considered as unipolar depressive for decades eventually experience a hypomanic or mixed episode (

Angst 2006).

Careful questioning for past mania and hypomania among those who present with major depressive episode is of utmost importance. While the bipolar nature of major depressive episode is evident for everybody if the patient has had a past manic episode, health professionals are usually less sensitized for detecting past spontaneous hypomania and past “treatment-associated” hypomania. A family history of bipolar disorder, early age of onset (

Benazzi and Akiskal 2008) and agitated unipolar major depression (

Akiskal et al. 2005) and other soft signs of bipolar spectrum disorder also deserve close attention (

Ghaemi et al. 2002).

Patients with those indicators of possible bipolarity are not only particularly vulnerable for affective switches when depressed, but might also be more prone to antidepressant resistance (

O'Donovan et al. 2008). In this follow-up study, almost all antidepressant resistant depressives (and those who become suicidal during antidepressant monotherapy) were found among the “pre-bipolar” depressives, as compared to pure unipolar depressives. Similar findings were published by

Woo et al. (2008).

Potentially insufficient treatment with antidepressant monotherapy in these cases might result in worsening both the short and long-term outcome including suicidal behaviours as a consequence of worsening of depression (

Rihmer and Akiskal 2006). In light of these it is not surprising that particularly juvenile depressives have been found to be vulnerable for “antidepressant-induced” suicidality, since early age of onset is among the best indicators of bipolarity in major depression.

Until recently, it has been widely assumed that evidence from the treatment of unipolar depression can be extrapolated to the bipolar syndrome. This has seemed justified by an acute symptomatology that is virtually undistinguishable. However, since the first edition of this guideline came out in 2002 (

Grunze et al. 2002), the available evidence for different medications in bipolar depression has markedly increased, and differences are being proposed. Some caution is needed, since simply to show efficacy in either unipolar or particularly bipolar groups cannot prove specificity. Indeed, unless equal effort is made to study both unipolar and bipolar patient groups, the claim for efficacy in one (and not the other) could be pseudo-specific. Moreover, the most obvious difference between the conditions lies in the potential for TEAS for patients with a bipolar illness history, rather than differential presentation of the depressed state per se.

Methods

The main focus of this guideline is on pharmacological treatments and while best practice regarding other physical treatments and psychotherapy will be summarised briefly, an evidence based review of these modalities is beyond the scope of the present paper. Although the authors are aware that bipolar disorder is a changeable condition which also shows common overlap of the different poles of mood (i.e. mixed mania and mixed depression), the guidelines are initially divided into the classical categories of acute treatments for bipolar depression and mania and prophylaxis. This article will concentrate on the treatment of bipolar depression in adults as there is, despite the clear clinical need (

Leverich et al. 2007), unfortunately a paucity of evidence for the treatment in children and adolescents. Due both to the lack of clear-cut and universally accepted diagnostic criteria, and the lack of controlled evidence for treatment, these guidelines will not cover depressive mixed states. There is no clear consensus where the dividing line runs between what some conceptionalize as bipolar mixed depressive state and others as unipolar agitated depression, especially when it comes to the importance of elated mood and motor activity (

Maj et al. 2003;

Benazzi 2004a,

b;

Akiskal et al. 2005;

Benazzi and Akiskal 2006). However, clinicians should be aware that patients with potentially manic symptoms while depressed constitute a different challenge (

Goldberg et al. 2009b), and some medications, e.g., antidepressants, are believed to require caution (

Goldberg et al. 2007).

We are also not able to differentiate on an evidence base between the treatment of bipolar depression with or without psychotic symptoms. Unfortunately, there are no controlled studies providing guidance on the drug treatment of bipolar depression with accompanying psychotic symptoms.

The methods of retrieving and reviewing the evidence base and coming up with an recommendation are identical to those described in the WFSBP guideline for acute mania (

Grunze et al. 2009). For those readers who are not familiar with the mania guideline, we will summarize the methods in the following paragraphs.

The results of metaanalyses have been used as a secondary source of evidence in the absence of conclusive studies or in the case of conflicting evidence. Metaanalyses often compile different drugs into one group, although the individual agents may be quite heterogeneous in their mode of action. In addition, they may have a number of methodological shortcomings, which can make their conclusions less reliable than those of the original studies (

Anderson 2000;

Bandelow et al. 2008). For bipolar depression, there are few metaanalyses available (e.g.,

Gijsman et al. 2004) and results and conclusions may be confounded by methodological issues (

Fetter and Askland 2005;

Ghaemi and Goodwin 2005;

Hirschfeld et al. 2005). Metaanalysis may pick up weak signals and magnify them to significance, e.g., in the case of lamotrigine (

Geddes et al. 2009); however, statistical significance should not be unthinkingly equated to clinical significance (the latter being also true for individual studies). In general, metaanalyses of negative primary data might identify a small effect size benefit as significant because of the power of Fisherian statistics.

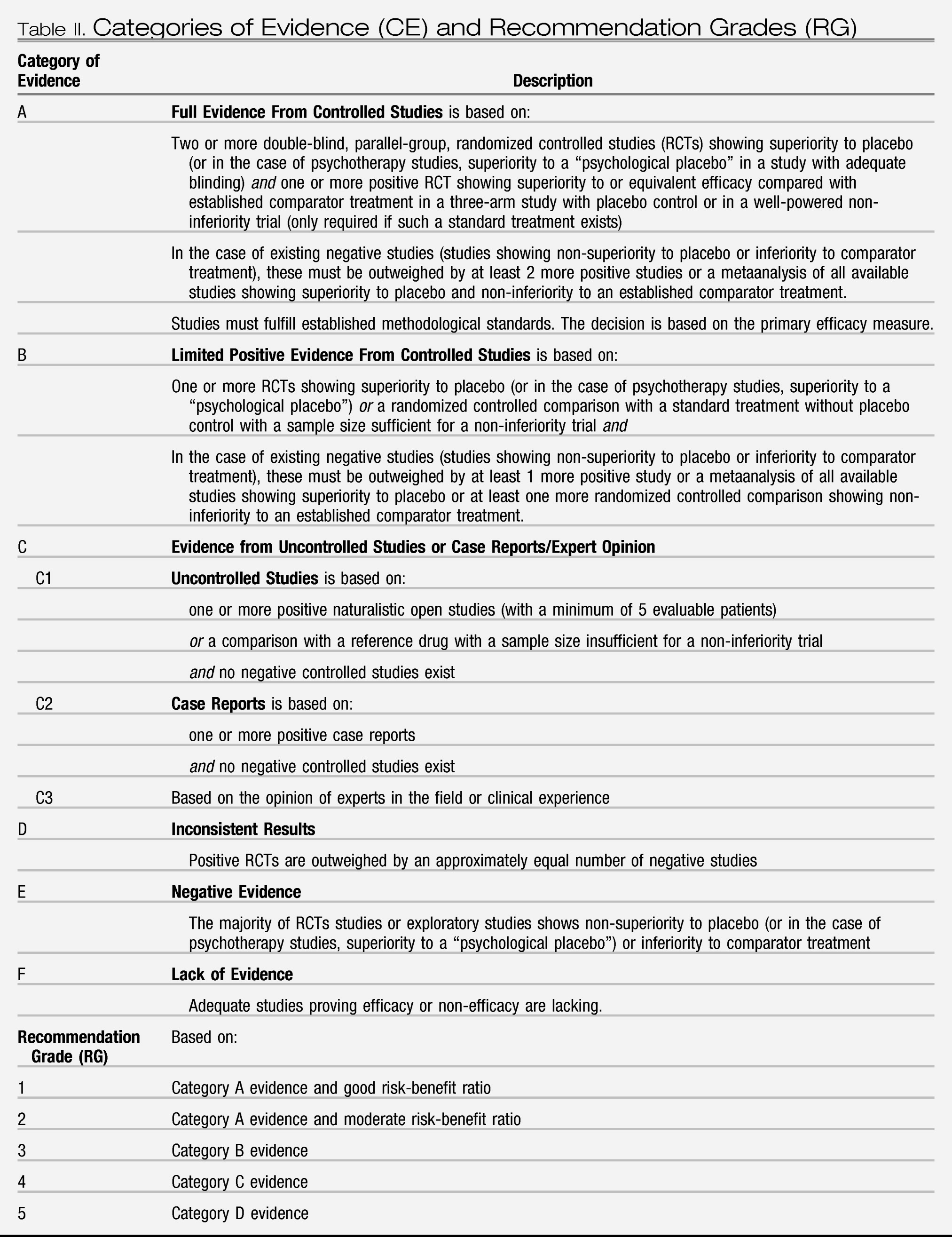

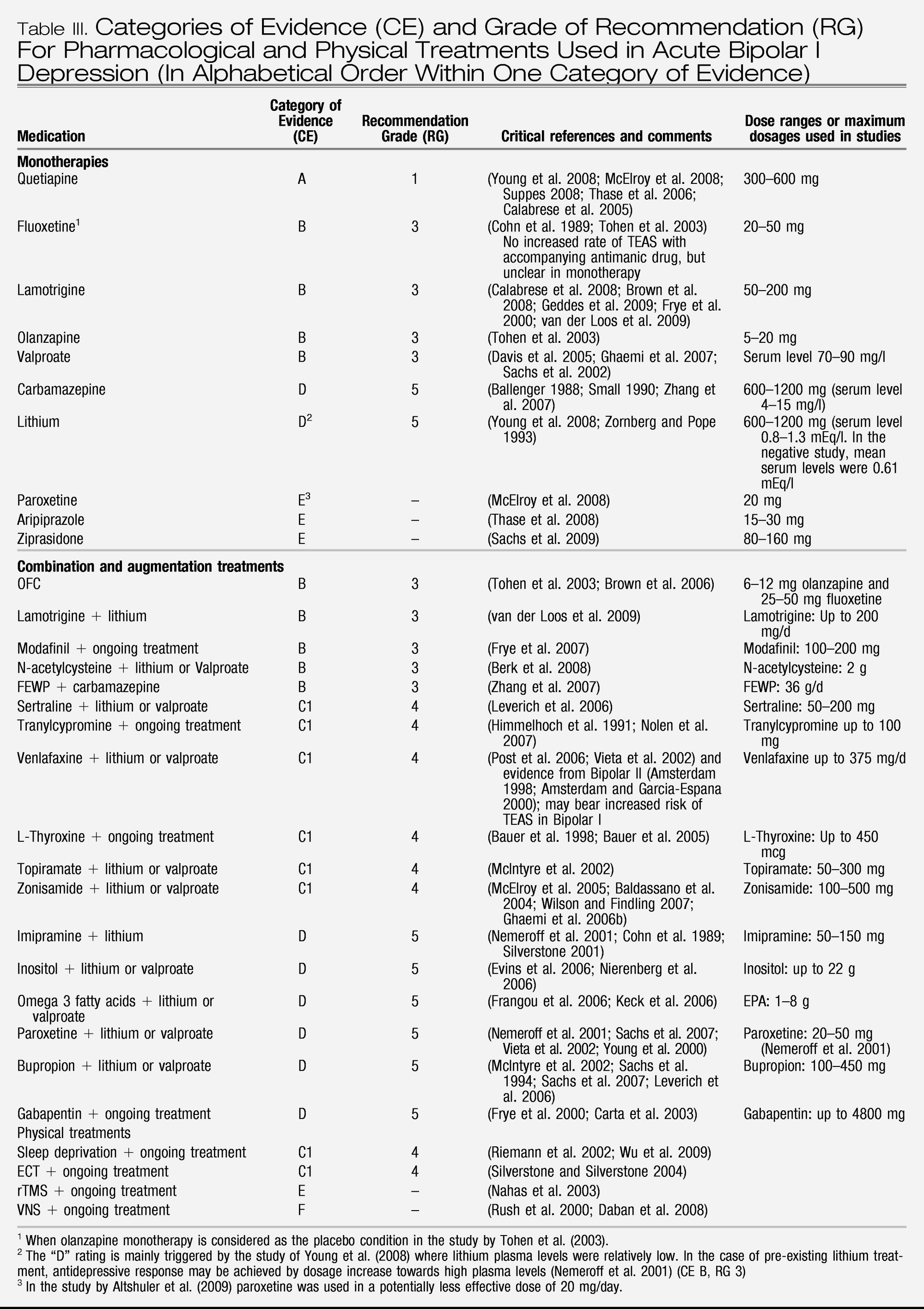

In order to achieve uniform and, in the opinion of this taskforce, appropriate ranking of evidence we adopted the same hierarchy of evidence based rigor and level of recommendation as recently used in other WFSBP guidelines (

Bandelow et al. 2008;

Grunze et al. 2009) (see

Table II). Depending on the number of positive trials and the absence or presence of negative evidence, different categories of evidence for efficacy can be assigned. Ideally, a drug must have shown its efficacy in double-blind placebo-controlled studies in order to be recommended with substantial confidence (categories of evidence (CE) A or B, recommendation grades 1–3); however, as detailed later, these strict criteria may be not suitable in bipolar depression due to a lack of conclusive evidence. A distinction was also made between “lack of evidence” (i.e. studies proving efficacy or non-efficacy do not exist) and “negative evidence” (i.e. the majority of controlled studies shows non-superiority to placebo or inferiority to a comparator drug). When there is lack of evidence, a drug with a potentially positive mechanism of action could still reasonably be tried in a patient unresponsive to standard treatment. Recommendations were then derived from the category of evidence for efficacy (CE) and from additional aspects as safety, tolerability and interaction potential. The grades of recommendation do not fully resemble what is generally understood as “effectiveness.” Clinical effectiveness is composed of efficacy, safety/tolerability and treatment adherence and persistence (

Lieberman et al. 2005). As we do not have reliable data on treatment adherence for most of the medications dealt with in this chapter, any statement on clinical effectiveness must be partially based on assumptions.

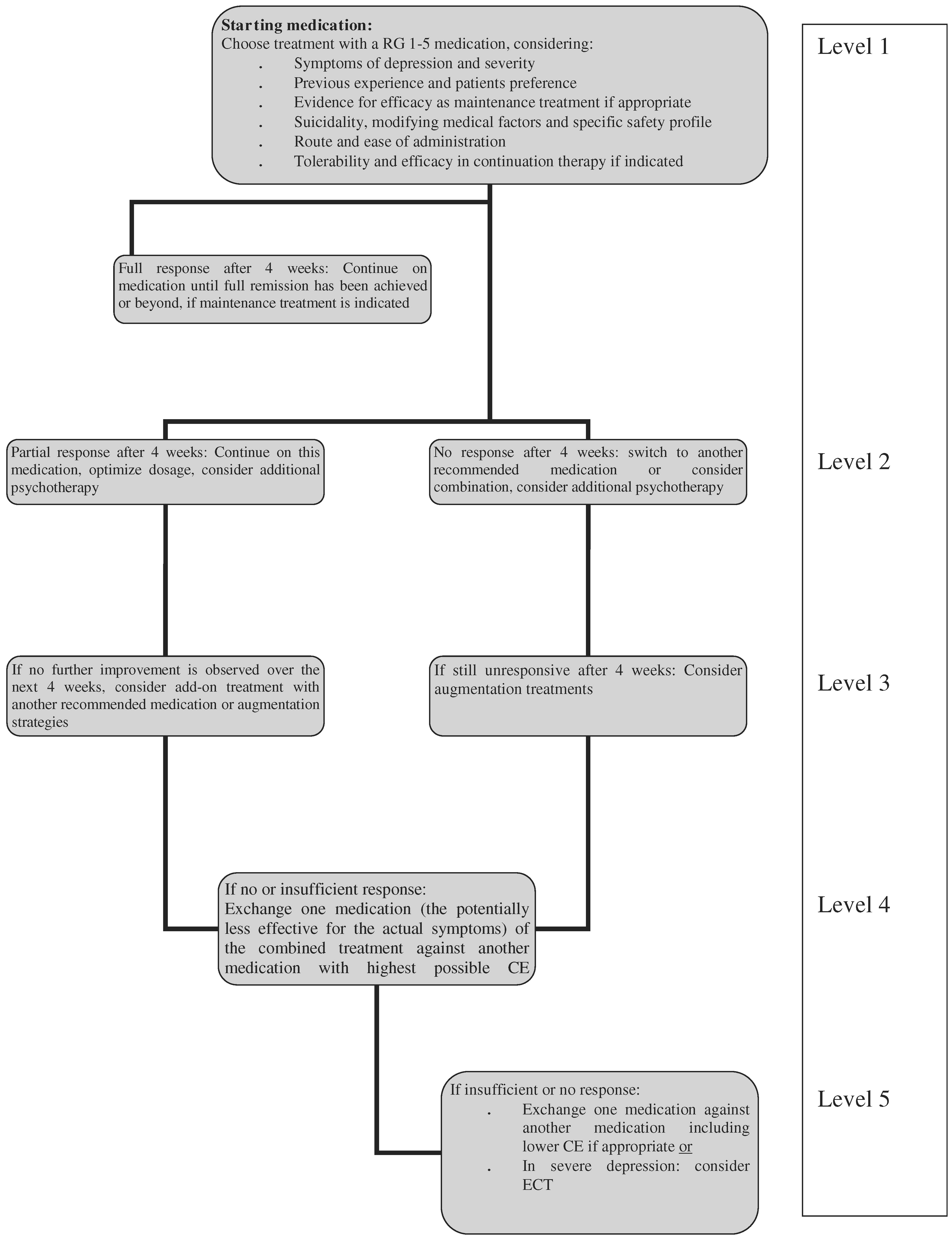

The recommendation grades (RG) can generally be viewed as steps: Step 1 would be a prescription of a medication with RG 1. When this treatment fails, all other Grade 1 options should ideally be tried first before switching to treatments with RG 2, then 3, 4 and 5. In some cases, e.g., the combination of an RG 1 and an RG 2 option can preferentially be tried instead of combining two RG 1 options, e.g., with some augmentation strategies. In the case of bipolar depression, the primary treatment may still be a medication with a RG as low as 5 as the RG 1 and 2 choices are rather limited and may not suit every patient. In addition, unequal quality of studies may substantially impact on CE and derived RG and even appear contradictory to clinical experience (see paragraph on valproate).

A general problem when reviewing trials is the question of adequate dosing of medication. For several medications, a dose-response relationship is known, especially from studies in unipolar depression. Established drugs which are used as internal comparators in sponsored three-arm studies might be underdosed as it is not in the interest of the sponsor that they came out as superior to the drug under investigation. Using this, although controlled, evidence could induce an unfair bias against established medication, as it might be the case with the two “EMBOLDEN” studies using paroxetine (

Young et al. 2008) and lithium (

McElroy et al. 2008), respectively, as comparators.

The WFSBP guideline series, including the bipolar guidelines, review acute and long-term treatment issues separately. They do not take into account long-term efficacy when addressing short-term treatment.This approach may be suitable for acute medical conditions, but the WFSBP Bipolar task force still feels uncertain whether an “episode” based approach is really the best way for a disorder which is almost characterised by the chronicity of its symptoms. This dilemma is most obvious in the case of lithium: Acute treatment data are not convincing enough for a higher category of evidence than “D”, however, when long-term considerations, including suicide risk, are taken into account lithium would clearly fall into a higher category (

Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 2006;

Young and Newham 2006).

We have not considered the direct or indirect costs of treatments as these vary substantially across different health care systems. Additionally, some of the drugs recommended in this guideline may not (or not yet) have received approval for the treatment of bipolar depression in every country, especially if they have been developed lately. As approval by national regulatory authorities is also dependent on a variety of factors, including the sponsor's commercial interest (or lack thereof) this guideline is exclusively based on the available evidence, not marketing authorisation.

Most RCTs in acute bipolar depression have a duration of 6–8 weeks, and only more recently have double-blind extension periods been added to the protocols. Thus, with the relative paucity of data, the clinically important question of maintenance of effect could not be considered as a core criterion for efficacy, but may become a supportive argument when a choice between similar effective medications has to be made.

Another unsolved issue is the choice of the appropriate rating scale for depression (

Möller 2009). Whereas older studies usually applied the Hamilton Rating scale for Depression (HAMD;

Hamilton 1967), either in its 17- or 21-item versions, more recent trials choose the Montgomery-Asberg Depression rating scale (MADRS;

Montgomery and Asberg 1979). There are subtle differences between these scales, and neither seems to adequately pick up symptoms more frequent in bipolar depression than unipolar depression such as hypersomnia, mood lability and psychomotor disturbances. Other, less frequently used scales in bipolar depression trials include the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (IDS, (

Rush et al. 1986), the self-rated Beck Depression Inventory (BDI;

Beck et al. 1961) and the Bech-Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale (MES) (

Bech 2002). An issue, which is often not considered is whether the available rating scales fulfil the criteria of unidimensionality by item response theory analysis (

Licht et al. 2005). Among the rating scales, the MES is the only scale that has been shown to fulfil such criteria. This heterogeneity of scales for the primary outcomes may have such an impact that it determines whether a study has a positive or failed outcome, e.g., as seen in one study with lamotrigine (

Calabrese et al. 1999a). Future studies may, subject to regulatory authorities' acceptance, use more specific scales as the Bipolar Depression Rating Scale (

Berk et al. 2007).

The task force is aware of several inherent limitations of these guidelines. When taking negative evidence into consideration, we rely on their publication or their presentation or the willingness of study sponsors to supply this information. Thus, this information may not always be complete and may bias evidence of efficacy in favour of a drug where access to such information is limited. This potential bias has been minimized as much as possible by checking the

www.clinicaltrials.gov data base; however, this does not work for older studies conducted prior to the implementation of this website. Another methodological limitation is sponsor bias (

Lexchin et al. 2003;

Perlis et al. 2005;

Heres et al. 2006;

Lexchin and Light 2006) inherent in many single studies on which the guidelines are based. Also, all recommendations are formulated by experts who may try their best to be objective but are still subject to their individual pre-determined attitudes and views for or against particular choices. Therefore, no review of evidence and guideline can in itself provide an unchallengeable recommendation but it can direct readers to the original publications and, by this, enhance their own knowledge base and anchor their treatment decisions more securely.

Finally, the value of any guideline is defined by the limitations of evidence. It is a particular additional problem that placebo trials in depression have become harder to conduct, and that those that have been conducted relatively recently tend to have higher placebo response rates. The necessary resources to do them properly can only come from an industry which has had little incentive to study bipolar depression until recently. In addition, one of the most important clinical questions that cannot be sufficiently answered in an evidence-based way is what to do when any first step treatment fails, which happens in a significant number of cases. Some studies, as the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD;

Sachs et al. 2003) tried to develop such algorithms, but results are not conclusive and cannot cover the large variety of treatment options (

Nierenberg et al. 2006). In particular, there are no systematic studies in bipolar depression that can guide the clinician when to switch medication. In the absence of other, more specific evidence, the task force suggests considering 4-week intervals for the different treatment steps. With the current level of knowledge we can only provide suggestive guidelines and not rigorous algorithms.

Once a draft of this guideline had been prepared by the Secretary and the principal authors it was sent out to the 53 members of the WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorders for critical review and addition of remarks about specific treatment peculiarities in their respective countries. A second draft, revised according to the respective recommendations, was then distributed for final approval to all task force members and, in addition, to the presidents of the 63 national member societies of the WFSBP.

Conclusions

Until recently, treatment of bipolar depression meant either monotherapy with antidepressants, preferably in combination with lithium or an antipsychotic or an anticonvulsant such as valproate or lamotrigine. The evidence for these options was, at its best, moderate, and a relatively slow onset of action is common to all of these. Antidepressants, lithium and lamotrigine have a substantial delay until they show full beneficial action, so additional symptomatic treatment with tranquilizers, e.g., lorazepam, is frequently needed.

Recently, quetiapine and OFC have broadened our treatment options, and both showed moderate to high effect sizes in controlled studies, together with an early separation from placebo, which may hint to a more rapid onset of action. Given the inherent danger of suicide in acute bipolar depression, this can be considered as a major step forward.

For many treatment options, the evidence is not straight forward but generated and extrapolated from several trials, most of them inconclusive by themselves. However, with reasonable caution, we can summarize some key findings:

•.

There is clear evidence of the efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy at 300 mg/day for the treatment of both Bipolar I and II depression, although there are both short-term tolerability issues and long-term safety issues which should be considered by the clinician and patient.

•.

There is strong evidence for the efficacy of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination. There are tolerability and safety issues with regard to this treatment as well which the clinician and patient must deal with.

•.

There is also fair evidence for the efficacy of fluoxetine and to some degree also for other antidepressants when used in combination with an antimanic agent, e.g., tranylcypromine, bupropion, sertraline, venlafaxine and imipramine. The issue of TEAS seems to be under control with the combined use of an antimanic agent, at least with SSRIs.

•.

Lamotrigine monotherapy in more severely depressed patients has been shown in a post-hoc pooled analysis to have efficacy. Lamotrigine as add-on to lithium in non- or partially responding patients should be considered.

•.

Although the evidence is not as good, add-on modafinil and add-on pramipexole (the latter in Bipolar II patients) should be considered.

Of the non-pharmacological treatments of bipolar depression, adjunctive psychological therapies such as CBT, IPT and social rhythm therapy can add to improved outcomes, although their main evidence base is in the prophylaxis of new episodes. As far as physical treatments are concerned, results for rTMS or VNS in bipolar depression are so far not encouraging or non-existing. ECT remains an effective option especially in treatment resistant bipolar depression.

The task force agrees that, although major advances have been made since the first edition of this guideline (

Grunze et al. 2002), there are many areas which still need more intense research to optimize treatment as also outlined in

Kasper et al. (2008): Bipolar II depression, psychotic bipolar depression, treatment of children, adolescents and the elderly with bipolar depression, treatment of patients with comorbid conditions, treatment of patients with suicidal risk, treatment of mixed depression, treatment of patients not responding to first or second step treatments and finally comparative studies between the different treatment options and identification of patient subgroups who may do best on a given medication or combination of medications. It is also mandatory to spend more thoughts on trial methodology given the continuous rise in placebo-response rates and, consecutively, failed studies. Clearly defined diagnostic groups and study entry criteria, together with careful site selection, are essential to achieve the best available evidence.

Statement of interests of principal authors

Heinz Grunze received grants/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last 3 years from Astra Zeneca, Bial, BMS, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Janssen-Cilag, Organon, Pfizer Inc, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, UBC and UCB Belgium.

Eduard Vieta received grants/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last 3 years from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bial, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest Research Institute, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen-Cilag, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer Inc, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Shering-Plough, UBC, and Wyeth.

Guy Goodwin received grants/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last 3 years from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, P1 Vital, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier and Wyeth.

Charles Bowden received grants/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last 3 years from Abbott Laboratories, Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, JDS Inc., Lilly Research, National Institute of Mental Health, Pfizer, R.W. Johnson Pharmaceutical Institute, Sanofi-Aventis, Repligen and the Stanley Medical Research Foundation.

Rasmus W. Licht received research grants, consulting fees and honoraria within the last 3 years from Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Glaxo-SmithKline, Janssen Cilag and Sanofi-Aventis.

Hans-Jürgen Möller received grant/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last 3 years from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Merck, Novartis, Organon, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Servier and Wyeth.

Siegfried Kasper received grants/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last 3 years from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSC, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Lundbeck, MSD, Novartis, Organon, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Schwabe, Sepracor, Servier and Wyeth.