The impact of surgical procedures for intractable epilepsy has demonstrated a range of outcomes, including improved seizure control, improved quality of life, and improved mood.

1–8 However, there has been concern, based on long-term follow-up studies, that de novo behavioral changes can occur in some patients after lobectomy, including psychosis and depression.

9–18 In this study, we assessed the impact of temporal lobectomy on mood in patients with intractable complex partial seizures (CPS) of unilateral temporal lobe origin. We also evaluated subjects with intractable CPS who did not meet criteria for surgery (i.e., CPS not localized to the temporal lobe). Specifically, we sought to explore 1) whether or not there was a difference in the prevalence of depression in epilepsy subjects with or without temporal lobe localization; 2) the effect of anterior temporal lobectomy on relieving prior depression; and 3) the incidence of de novo major depressive episodes after lobectomy.

RESULTS

Patient Groups

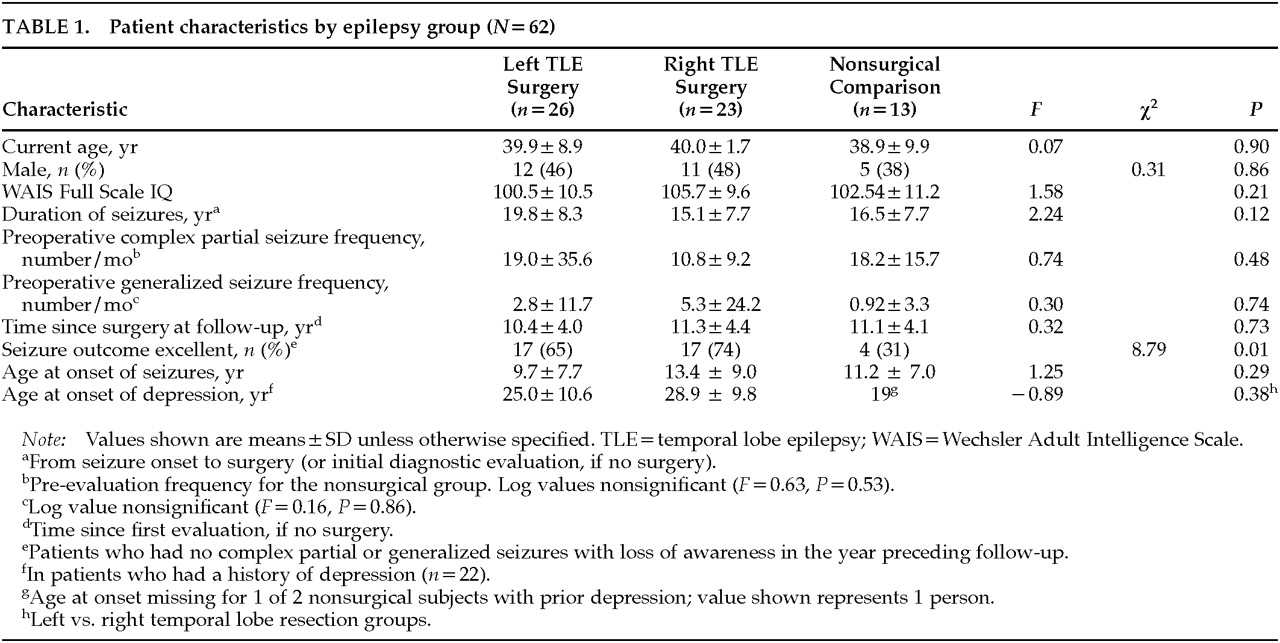

Clinical parameters of the left (LTE) and right (RTE) temporal lobe epilepsy surgery patients and nonsurgery patients are shown in

Table 1. No significant differences were found across the groups in age, IQ, age at onset of seizures, seizure duration, preoperative seizure frequency, or age at onset of depression in those with a history of depression. Analyses comparing the parameters of the temporal lobe epilepsy surgery group as a whole (RTE+LTE) with the nonsurgical comparison group yielded similar results. At follow-up, the seizure outcome of the left-sided and right-sided lobectomy patients did not differ (χ

2=1.4,

P=0.24). However, both surgical patient groups had significantly better seizure outcome at follow-up than the nonsurgical (NS) patient group (LTE vs. NS: χ

2=4.2,

P=0.04; RTE vs. NS: χ

2=8.6;

P=0.00).Sixty-five percent of the temporal lobe surgery patients and 100% of the nonsurgical patients were on anticonvulsants at the follow-up evaluation (χ

2=6.2, df=1,

P=0.013). The most frequent medications were carbamazepine (50%), phenytoin (18%), and valproic acid (11%).

Surgical Patients: Complications and Histology

Of the 49 patients who underwent surgery, 6 had permanent complications. Three left temporal lobe surgery patients had hemiparesis and hemianopsia. A fourth left-sided surgery patient experienced diplopia. One right-sided surgery patient experienced a third cranial nerve palsy. Another right-sided surgery patient experienced dysplagia.

Of the 49 patients who had temporal lobe resections, 42 patients had adequate histological analyses of the hippocampus. Of these 42 patients, 41 had mild to moderate hippocampal sclerosis. Only 1 patient did not have hippocampal sclerosis. This was a male patient with a history of major depression who had had a left temporal lobectomy. Extrahippocampal lesions were documented in 10 of 49 patients. These included 1 patient with glioma, 4 patients with hamartomas, and 5 with heterotopias.

Overall Psychiatric Findings

Of the 62 subjects, 31 (50%) met criteria for a DSM-III-R lifetime psychiatric diagnosis. Twenty-four (39% of the total sample) met DSM-III-R criteria for a major depressive episode, 3 (4.7%) for an anxiety disorder, 1 (1.6%) for bipolar disorder, and 1 (1.6%) for substance abuse. Two patients (3%) met criteria for the “depressive disorder not otherwise specified” category.

Depression in Patient Groups

Of the 62 subjects, 22 (45%) of the 49 patients who underwent surgery met criteria for a lifetime history of at least one major depressive episode, compared with only 2 (15%) of the 13 nonsurgical control patients (χ2=3.8, df=1, P=0.05). That is, those with seizures clearly originating from the temporal lobe had a significantly greater lifetime prevalence rate of depression than those without demonstrable temporal lobe involvement. Fifty-four percent of those with left temporal lobe epilepsy and 35% of those with right temporal lobe epilepsy met criteria for a lifetime history of major depression (χ2=1.7, df=1, P=0.18). Thus, there was no significant laterality effect for lifetime prevalence rate of depression.

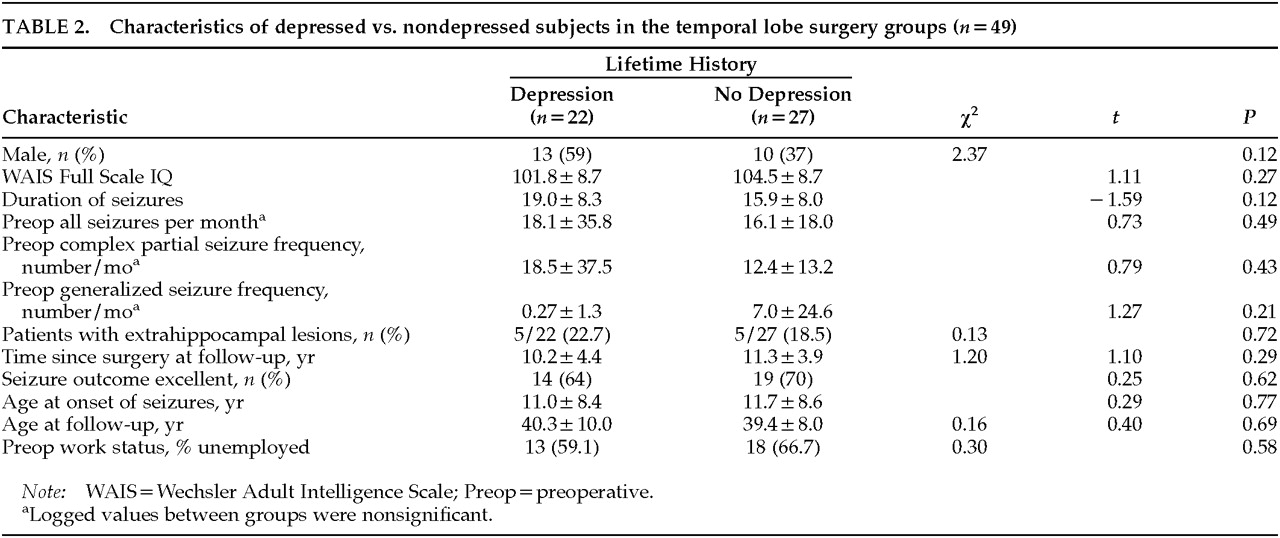

Table 2 shows characteristics of the lobectomy group with and without lifetime history of depression. Overall, the group with a history of depression did not differ significantly from the nondepressed group on IQ, age of onset of seizures, duration of seizures, prior exposure to phenobarbital, or preoperative work status, where “employment” included working for pay, full-time student, or full-time homemaker duties. Men tended to be overrepresented in the depressed group, accounting for 59% of the group. Of the 23 men in the lobectomy cohort, 13 (57%) had a history of depression. Of the 26 women, 9 (35%) had a history of depression, although the difference was not significant (χ

2=2.37,

P=0.12). No significant differences emerged for preoperative work status (percentage employed) between the cohorts with and without a history of depression. Preoperative work status was assessed both including and omitting “full-time homemaker” from the “employment” model. No significant differences emerged in either analysis.

There were no significant differences in the presence of extrahippocampal lesions between patients with or without major depression: 5 (50%) of the 10 patients with extrahippocampal lesions had a history of depressive episodes, versus 17 (44%) of the 39 without such pathology (χ2=0.13, df=1, P=0.72).

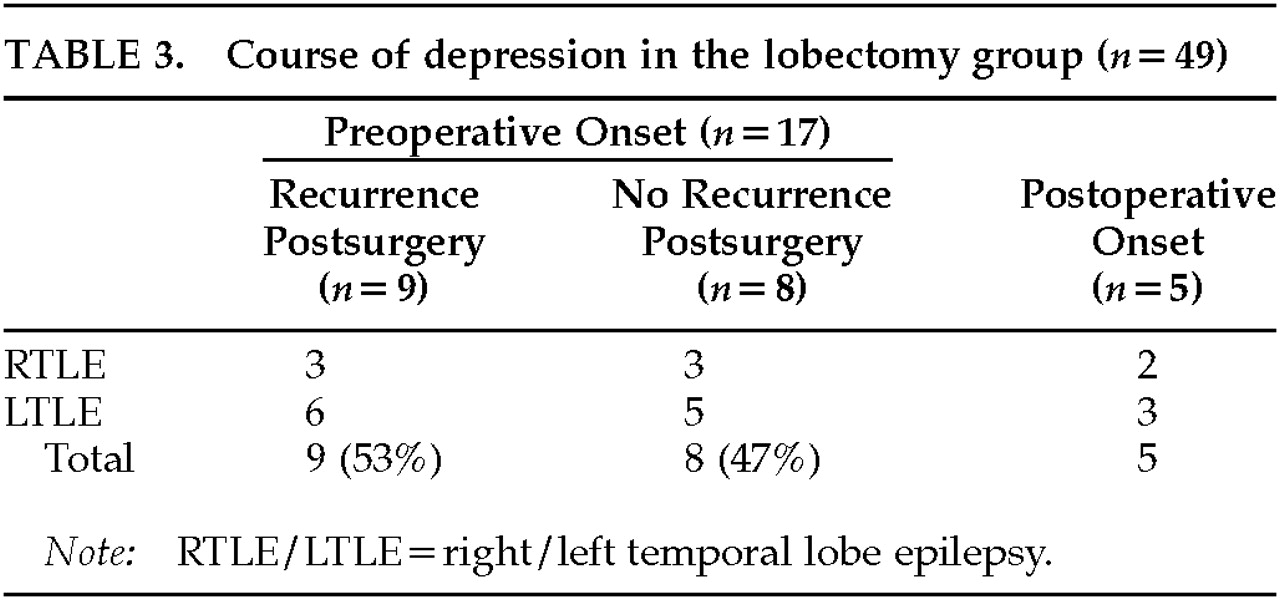

Of the 22 patients who had a lobectomy and a lifetime history of major depression, 17 (77%) had depression histories that preceded the lobectomy (11 left temporal epilepsy, 6 right temporal lobe epilepsy). Of those with preoperative episodes of depression, 8/17 (47%) experienced no recurrence of depression after lobectomy, and 9 (53%) continued to have episodes postsurgery (

Table 3). These two groups did not differ significantly in preoperative seizure frequency, histological findings, or the number of medications given postsurgery. However, 7 of the 8 patients with resolution of depression after lobectomy had excellent seizure outcome after surgery, compared with only 4 (44%) of 9 patients who had a recurrence of depression postsurgery (Fisher's exact test,

P=0.13). Five surgical patients developed new-onset depression postoperatively (3 patients with left lobectomy and 2 with right lobectomy). Four of the 5 de novo postoperative depressions (80%) occurred within the first year postsurgery. Three of the 4 who developed depression within the first year had left temporal lobe surgery complicated by hemiparesis and aphasia. All entered rehabilitation. The 2 patients with right temporal lobectomy had no surgical complications but developed depression de novo 1 year and 3 years postoperatively.

Potential Medication Effects

Eighty-two percent (40/49) of patients who eventually underwent temporal lobe surgery versus 100% (13/13) of patients whose seizures were not localized to a temporal lobe had had a trial of phenobarbital by the time of their initial surgical evaluation (χ2=2.8, df=1, P=0.095). There were no differences between the groups of patients who eventually underwent temporal lobectomy and those who did not have surgery (chi-square analyses, all P<0.10) based on whether or not they had had 1) a regimen of valproic acid, 2) carbamazepine, or 3) a regimen of either valproic acid or carbamazepine. Chi-square analyses indicated that a history of major depression was not significantly associated with a history of a regimen of phenobarbital, valproic acid, and/or carbamazepine. This was true for both the patient groups combined (surgical and nonsurgical) and for the group limited only to patients who eventually had temporal lobe surgery. Further, there was no relationship between use of phenobarbital or valproic acid and/or carbamazepine and onset of depression prior to surgery (either for the surgery groups combined or for the temporal lobe surgery group only).

DISCUSSION

It is first notable that within this population of patients with refractory complex partial seizures, the lifetime prevalence of depression was high (39%), almost double that of recent lifetime prevalence estimates in the general population.

22 An increased prevalence of depression in patients with epilepsy compared with normal control subjects has been reported previously in a number of studies.

23–26 In our sample, depression was associated with seizures of the temporal lobe to a greater degree than with seizures not having a clear primary temporal lobe onset. Further, epilepsy preceded the first episode of depression in all subjects, usually by more than a decade (

Table 1).

Although it is possible that depression in this population is the result of having a chronic illness,

27–29 an alternative explanation is that there is a pathophysiologic relationship between temporal lobe dysfunction and vulnerability to developing depression.

30,31 Several features of the design of our study limit the testing of this hypothesis. The comparison group is small and the seizure foci are not localized in the majority of these cases, making it difficult to conclude there is absolutely no temporal focus in the comparison patients. Further, since all of the study subjects were referred for intractable seizures, severity of illness is presumably higher in both cohorts than in the majority of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Thus, whether the presence of depression in epilepsy patients is greater in those with or without a temporal lobe localization may be better tested in groups with less severe, and potentially more circumscribed and limited, temporal lobe disease. However, studies of primary depression have implicated the limbic system in the regulation of mood. Hypoperfusion on SPECT or hypometabolism on PET in the anterior temporal lobe, inferior frontal lobe, and anterior cingulate have been identified as the predominant regional abnormalities seen in patients with primary clinical depression.

32,33 Similarly, Bromfield et al.

34 found significant inferior frontal lobe hypometabolism in patients with left temporal lobe epilepsy and depression compared to those with LTE and no depression. In another cohort of patients with epilepsy and depression, Victoroff et al.

35 found that in patients with TLE, the combined main effects of interictal left temporal lobe hypometabolism and a high degree of overall hypometabolism both were significantly associated with major depression. This finding suggests that dysfunction in the temporal lobe due to an epileptogenic focus may cause hypometabolism within the temporal lobe and at distal sites functionally connected to the temporal lobe (e.g., frontal lobes). This hypometabolism may reflect neurochemical changes that increase the vulnerability toward depression.

There have been very few systematic studies comparing mood in patients with focal temporal lobe epilepsy and those with extratemporal foci. Recently Perini et al.

36 demonstrated higher rates of depression in patients with TLE than in those with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Similarly, we found higher cross-sectional rates of depression in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy in comparison to those with absence seizures.

37 In other studies, depression and anxiety have been shown to occur at similar rates in those with temporal lobe and with other epilepsies.

29–31,38–41 Limitations in methodology exist in all of these studies (i.e., data reported in mean scores rather than cutoff scores for depression; cross-sectional evaluations with symptom scales used to assess depression rather than historical interviews or longitudinal observations; number of patients with TLE who also have secondary generalization not reported) and make it difficult to compare results across studies. The present study assessed lifetime prevalence of major depression as opposed to cross-sectional current symptomatology. Only one other study besides the present one assessed lifetime psychiatric histories: 62 patients with TLE and 70 patients with grand mal generalized epilepsy were assigned diagnoses in accordance with DSM nomenclature.

42 With this approach, the investigators found that the groups differed significantly on DSM categories, and the group with TLE had more than twice the rate of lifetime depression of the grand mal generalized group.

Although patients with left temporal lobe epilepsy have been reported to have higher lifetime rates of depression than those with right temporal lobe epilepsy, there was no significant difference in the present study. Prior studies

23,31,35,43–45 including our own,

37 have found an association between left temporal lobe or left hemispheric epilepsy and depressive symptomatology, but this has not always been observed.

46–51 In the current study, half of those with left temporal lobe epilepsy met lifetime criteria for a major depressive episode and one-third of those with right temporal lobe epilepsy met the criteria. It is possible that a Type II error occurred because of our small sample size. Given the discrepancies in the literature, however, the issue of whether having left-sided TLE increases the risk for depression remains unresolved.

Rates of depression among men (57%) were higher than among women (35%) in the present study, which contrasts with the epidemiologic surveys in the general population, where lifetime depression occurs twice as frequently in women as in men.

22 The high rates of depression in men are cause for concern and perhaps can be accounted for by changes in role function secondary to epilepsy, rather than by epilepsy variables per se. The majority of male subjects were disabled by their epilepsy and unemployed. However, men in the nondepressed group were equally as likely to be unemployed. Thus, employment status alone did not (in the regression model) differentiate between the depressed and the nondepressed men.

Of the temporal lobectomy patients with a lifetime history of depression, the majority (77%) had their first episode of depression prior to surgery, and 47% of those experienced continued relief from depression after surgery (follow-up period ranging from 3.3 to 16.5 years; mean 9.6±5.2 years). This improvement for some patients with depression contrasts with the previously reported lack of improvement in psychosis after surgical intervention

1,10,12,15 and supports the notion that depression per se is not a contraindication for considering surgery.

The exact factors that contribute to resolution of the depression remain to be clarified. In one study, Hermann and Wyler

52 found that depression declined significantly only in those patients rendered completely seizure-free by anterior temporal lobectomy. In their study, those patients with greater than 75% improvement but continued seizure activity had no change in self-reported depression. A recent study of a large cohort of patients, including some patients from the current study, reported that self-rated depressive mood improved only in those patients whose seizure outcomes were excellent.

53 These reports are in agreement with a recent study demonstrating that complete absence of seizures after surgery was a predictor of excellent psychiatric outcome.

18 Our study further examined depression and seizure outcome but assessed clinical major depression, not self-rated mood. Our results, although not significant, suggest that seizure outcome may affect the likelihood of recurrence of major depression; 7 of the 8 patients with no depression recurrence after lobectomy had excellent seizure outcomes. Further study with a larger sample may clarify this relationship.

Ten percent of the temporal lobe surgery patients developed de novo depression after lobectomy, with the majority of onsets occurring in the first year postsurgery. Our rate is similar to rates of de novo depression after lobectomy previously described in the literature.

4,5,13,17 Bruton

13 examined clinical depression rates before and after surgery in 149 patients undergoing lobectomy. Only 1 patient was depressed preoperatively, but 10% developed a postoperative affective disorder. More recently, Naylor et al.

54 performed retrospective psychiatric interviews (using the Present State Examination and ICD-10) on patients who had undergone lobectomy. Three patients (8%) developed de novo postsurgical depression. No association was found between the presence of psychiatric disorder and laterality or histopathology. Bladin

16 found depression to occur at a lower rate after lobectomy: in 107 postlobectomy subjects, 5 (<5%) experienced postoperative depression. No data on laterality or other seizure variables were given. Furthermore, whether these were cases of new-onset depression or reemergence of a prior illness was not stated. These studies suggest that some patients with lobectomy may develop de novo depression but that it is not a common sequela of lobectomy. Risk factors that may contribute to new onset of depression after lobectomy remain to be further explored.