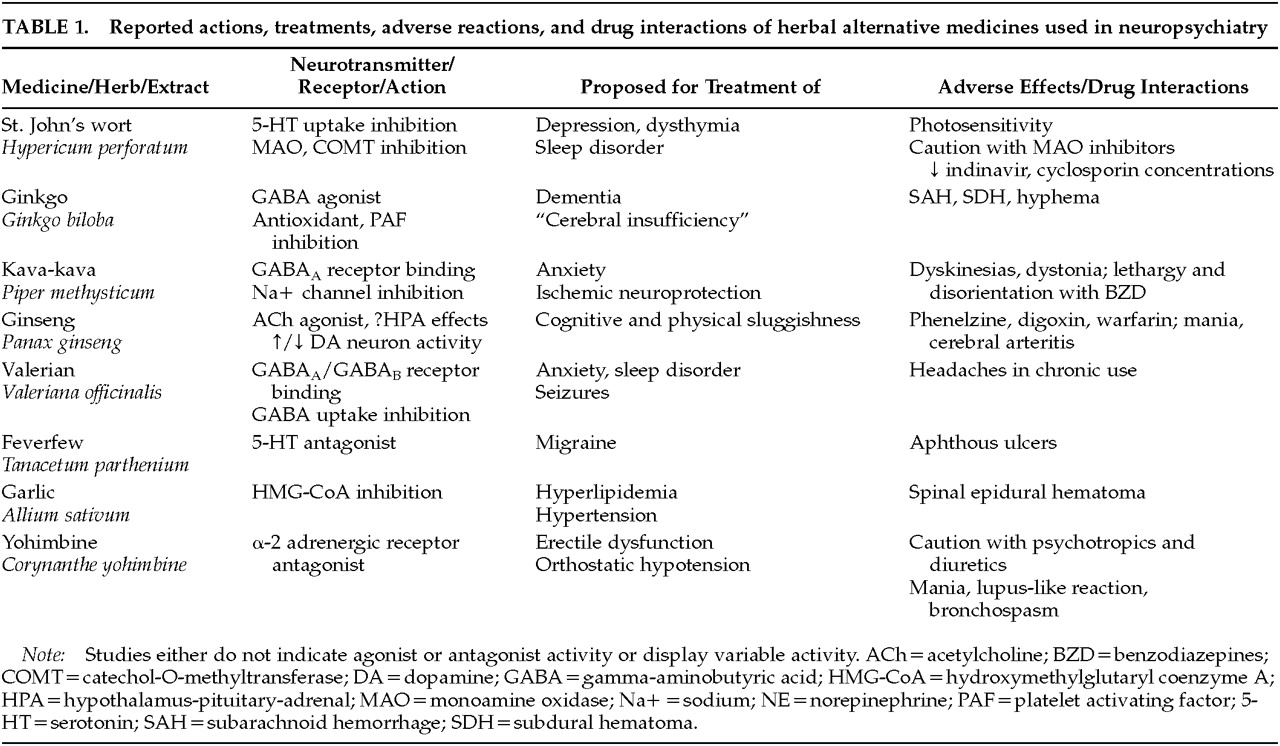

The following medicines will be reviewed: St. John's wort for depression, ginkgo for dementia, kava for anxiety, ginseng for cognitive and mood enhancement, valerian for insomnia, feverfew for migraine prophylaxis, garlic for atherosclerosis and stroke risk reduction, and yohimbine for erectile dysfunction. In light of the neuropsychiatrist's interaction with patients who have multiple sclerosis and HIV infection, the widely used immune stimulant echinacea is also reviewed. (Although frequently used today, nonherbal alternative treatments such as melatonin and S-adenosyl-methionine are not included in this review.)

St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

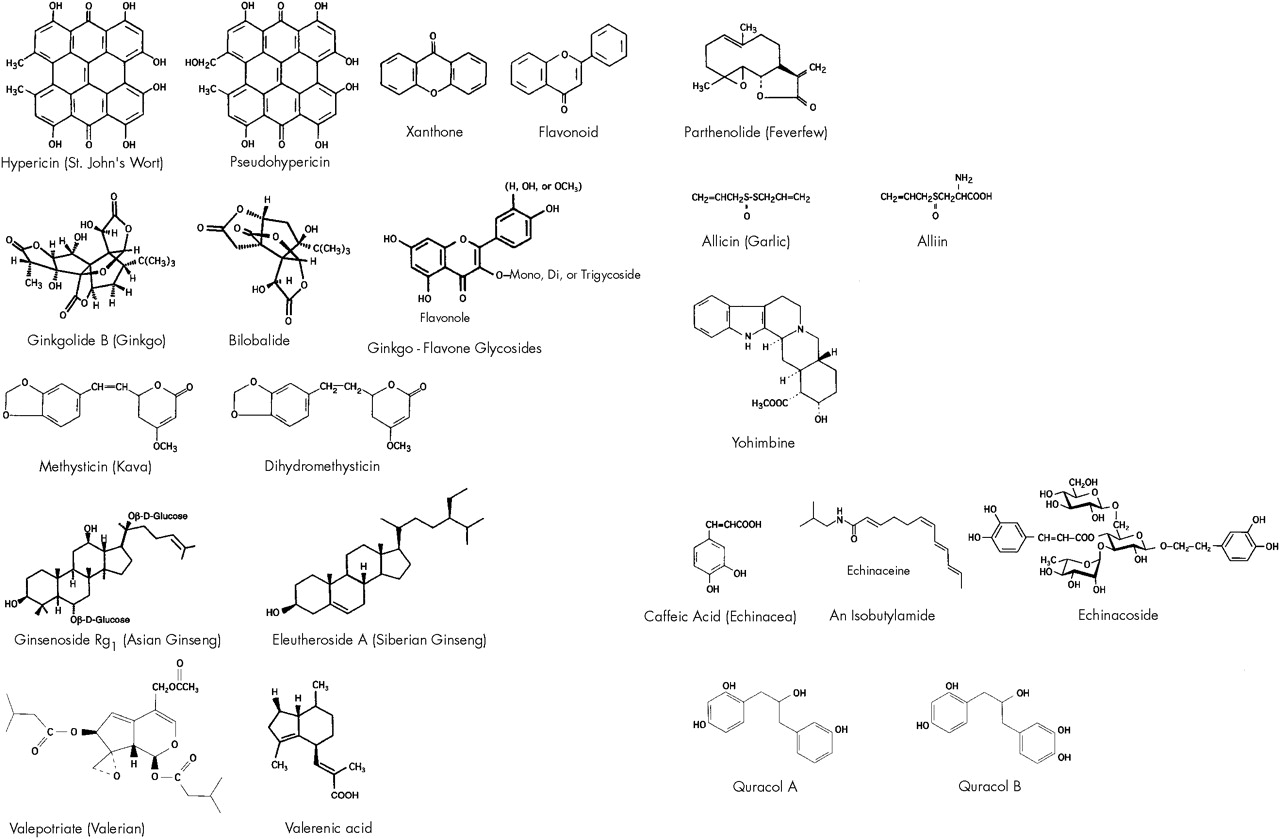

The aromatic perennial St. John's wort (SJW) has been prescribed in Germany as Johanniskraut over the past decade for treatment of depression, dysthymia, and sleep disorder. The leaves and yellow flowering tops yield about 0.1% hypericin, pseudohypericin, and related naphthodianthrones. Flavonoids, aromatic oxygen heterocyclic compounds found in certain plants, have also been identified in the plant.

31The plant's antidepressant mechanism of action initially was stated to be monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibition, based on studies by Suzuki et al.;

32 however, this finding was later attributed to a test product of only 80% purity. Crude plant extract xanthenones have demonstrated MAO inhibition in rat brain studies, but it is unclear if hypericin itself inhibits MAO-A or -B in the human nervous system. Plant fractions containing xanthones and flavonoids demonstrate marked MAO-A inhibition.

33 Other unidentified components of the herb inhibit catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and suppress interleukin release.

34 Supporting the biogenic amine antidepressant effect of SJW, Perovic and Müller demonstrated hypericum extract inhibition of serotonin (5-HT) uptake in rat synaptosomes.

35 It is not known whether the active components of hypericum are able to cross the blood–brain barrier.

36A 1996 European meta-analysis of hypericum in 23 randomized controlled trials in 1,757 outpatients concluded the herb extracts were more effective than placebo and were comparable to conventional antidepressants (ADs) in the treatment of mild to moderate depression.

37 The side effect profile was better for hypericum than for conventional ADs. Side effects were experienced by 50 patients (19.8%) taking hypericum versus 84 (52.8%) given standard ADs. This study analyzed data from 15 placebo-controlled trials (largest

N=120) and 8 controlled trials in which hypericum was compared with ADs (largest

N=135). The limitations of the studies reviewed included short duration (4 to 8 weeks), lack of diagnostic precision with strict DSM/ICD criteria, the use of variable hypericin extract dosages, and lower standard antidepressant dosages (less than what most American psychiatrists consider therapeutic).

38 Of the studies included in the meta-analysis, particularly noteworthy are the Hänsgen et al.

39 and the Harrer et al.

40 studies for evaluation of hypericum versus placebo and versus maprotiline, respectively, in a DSM-III-R/ICD-10 depressed population.

In 1997, the NIMH OAM and Office of Dietary Supplements provided funding for a multisite study to investigate hypericum in the treatment of depression. The three-arm study will compare hypericum, placebo, and sertraline in 300 patients with major depression.

SJW, also known as “goat weed” and “klamath weed,” is generally given orally at a dose of 300 mg, with 0.3% concentration (900 μg) of hypericin, three times daily. Onset of its mood-elevating effect usually occurs after several weeks.

41 Pharmacologically, serum concentrations of hypericin peak in 5 hours and reach steady state in 4 days.

42 The plasma half-life (t½) of pseudohypericin varies from 16.3 to 36 hours. The plasma t½ of hypericin is about 25 hours.

Interactions between SJW and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), dopaminergics, and sympathomimetics are unclear. Because of the potential for severe hyperpyretic or hypertensive crises, convulsions, or death, it is recommended that patients taking MAOIs not take SJW.

13 Theoretically, SSRIs, dopaminergic agonists, and sympathomimetic agents may pose a risk when coadministered with hypericin.

The effect on cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes was unknown until recently. Naphthodianthrones in SJW induce the CYP450 3A4 isoenzyme, potentially leading to the alteration of therapeutic levels of antivirals, immunosuppressants, anticoagulants, anti-arrhythmics, and oral contraceptives. The FDA released a public health advisory in February of this year on the risk of drug interactions with indinavir, a protease inhibitor, and other drugs metabolized by the CYP450 pathway. The recommendations in the advisory are based on a recent NIH study revealing a 57% area under the curve mean reduction of indinavir with SJW administration in 8 health non–HIV-infected volunteers.

42a Because of the possibility of suboptimal antiretroviral drug concentrations leading to loss of virologic response, the advisory also recommended against concomitant administration of SJW with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

Two cases of acute cardiac cellular transplant rejection secondary to SJW-induced cyclosporin level reduction are described in a

Lancet research letter.

42b The 2 patients underwent heart transplantation 11 to 20 months prior to rejection for endstage ischemic cardiomyopathy. Both patients had event-free courses on the triple immunosuppressive regimen, cyclosporin, azathioprine, and low-dose corticosteroids. Within 3 weeks of beginning SJW (1 self-medicated and 1 prescribed by a psychiatrist), the patients presented for elective endomyocardial biopsy and were found to have subtherapeutic cyclosporin serum concentrations.

Prior to the

Lancet publications, known adverse reactions with hypericin included photosensitivity in grazing animals and in one human report.

36 The side effect profile includes gastrointestinal symptoms, allergic reactions, fatigue, dizziness, and xerostomia, and these occurred in 0.6% or less of 3,250 treated patients.

43 Woelk et al.

43 reviewed studies reporting the frequency of undesired effects with ADs to range from 2.5% (headache) to 17.6% (dry mouth). A 1.5% dropout rate in the hypericum-treated patients, versus reports of 3% to 12% dropout rates with ADs, was also noted.

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba)

Ginkgo comes as a concentrated extract from the

G. biloba tree and is traditionally used as a treatment for improving mental alertness. Major components of the extract are flavonoids (ginkgo-flavone glycosides) and terpenoids (ginkgolides and bilobalide).

44 These compounds are thought to act as free radical scavengers, providing cellular membrane protection and inhibiting platelet-activating factor (PAF), respectively.

45 Bilobalide (but not ginkgolides) suppressed hypoxia-induced choline release from rat hippocampal slices when subjected to an oxygen-free buffer.

46 Oral bilobalide also significantly increased gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels and glutamic acid decarboxylase activity in mouse brains as compared with controls.

47 Finally, ginkgo extract administration increased the hippocampal muscarinic receptor population in aged rats, suggesting a possible prophylactic effect for ginkgo in the aging brain's normal decline in cholinergic function.

48Ginkgo has been prescribed in the United Kingdom over the past two decades for treatment of “cerebral insufficiency” (CI). CI is an inexact term used in Europe and is considered to indicate dementia secondary to impaired cerebral circulation. The symptom complex, roughly equivalent to vascular dementia, includes memory and concentration difficulties, absent-mindedness, confusion, anergia, tiredness, decreased physical performance, depressive moods, anxiety, dizziness, tinnitus, and headache.

49In Germany, the nootropic, or cognitive-enhancing, effects of ginkgo have been studied in patients with multi-infarct dementia or mild to moderate Alzheimer's dementia. A 24-week prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial evaluated ginkgo in 156 patients.

50 The investigators used the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale “for psychopathological assessment,” the Syndrome Short Test (SST) for assessment of attention and memory, and the Nuremberg Geriatric Observation Scale for behavioral assessment of activities of daily life.

51 The study demonstrated significant differences in responder rates on the CGI (32% vs. 17% placebo) and the SST (38% vs. 18% placebo), favoring the ginkgo-treated group. (Responders were defined as those scoring “much improved” or “very much improved” on the CGI and showing a decrease of at least 4 points on the SST.)

In the United States, a 1-year randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter study with 120 mg of ginkgo extract (EGb) monitored cognitive impairment, daily living activity, and social behavior in 202 patients with Alzheimer's disease or multi-infarct dementia. Both cognitive and behavioral performance improved for 6 months to 1 year: 27% of ginkgo-treated subjects (vs. 14% on placebo) attained at least a 4-point improvement on the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS), and 37% were considered improved (vs. 23% placebo) on the Geriatric Evaluation by Relative's Rating Instrument.

52 (These data can be compared contextually with the donepezil data from the 24-week trial, where 53.5% of subjects improved 4 ADAS points versus 26.8% on placebo.

53) Although caregiver and cognitive tests demonstrated differences favoring the treated group in the ginkgo study, treatment effects were not detected by clinicians on the CGI.

52One major criticism of the study is the inclusion of the vascular dementia subgroup in the analysis of the Alzheimer's patient data. Another criticism is that the primary efficacy analysis was influenced by the substantial dropout rate after the halfway point in the study, necessitating secondary analysis based on intent-to-treat methodology. Of the 327 patients randomized to EGb or placebo, only 137 (78 and 59, respectively) completed the trial. Using the last observation carried forward to end could have produced an underestimate of the extent of natural deterioration of patients in the study. The NIH currently is sponsoring a three-and-a-half-year trial of ginkgo to study the prevention of Alzheimer's disease in people age 75 years or older without dementia.

Ginkgo also has been studied in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of ginkgolide B in patients with acute multiple sclerosis (MS) exacerbations.

54 This study showed no significant differences in ratings on functional scales with treatment. The MS study followed positive trial results examining PAF antagonism in rats with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis, the most widely used animal model of MS.

55,56 Investigating PAF antagonist activity in the mixed ginkgolide compound, BN52063, Chung et al.

57 demonstrated the compound's inhibition of platelet aggregation with human platelets.

The only side effect in the MS study was singultus (hiccups).

54 The GCEm report other side effects as infrequent, including dyspepsia, headache, and allergic skin reactions.

13 Although no severe side effects have been noted anecdotally, adverse reactions have been noted in various journal letters and case reports. Subarachnoid hemorrhage was reported in a 61-year-old man without other risk factors who was taking ginkgo 40 mg, three to four tablets per day.

58 It was suggested that bleeding was induced by the extract's potent inhibition of PAF and association with increased bleeding time. Spontaneous bleeding into the anterior chamber of the eye was noted in a 70-year-old man after taking gingko 40 mg twice daily along with aspirin,

59 again implicating ginkgolide-B PAF inhibition. A 33-year-old woman who developed bilateral subdural hematomas had a prolonged bleeding time while taking ginkgo 60 mg twice daily.

60Ginkgo is sold over the counter (OTC) in strengths of 40 mg to 60 mg in the United States. Most of the trials testing ginkgo in CI used 120 to 160 mg per day given in three divided doses. Increased dose efficacy has not been demonstrated in studies up to 240 mg. Peak absorption of flavone glycosides is attained in plasma within 2 to 3 hours and the t½ is 2 to 4 hours. Clinical effects may not be apparent for 4 to 6 weeks.

61 There are no reports of interactions with psychiatric medications.

Kava-kava (Piper methysticum)

Kava is a member of the pepper family and contains psychoactive kava-pyrones. Polynesian islanders consume the extract as a beverage to experience a calming and relaxing effect without cognitive disturbances. Kava-pyrones possess a six-membered unsaturated lactone ring bound to a benzol ring by means of an ethylydene bridge.

62 The α-pyrone constituents have been reported to possess anticonvulsive properties. Kavain, a synthetic kava pyrone, displayed inhibition of voltage-dependent sodium channels in rat cerebrocortical synaptosomes.

63Anticonvulsants have also shown reduction of brain injury from ischemia, and this property led to an investigation of whether kava was able to reduce cerebral infarct size in animals. Studies of the neuroprotective aspects of the kava extract and its constituents, methysticin and dihydromethysticin, have demonstrated protection against focal cerebral ischemia in rodents.

64 The demonstration of selective binding to GABA

A receptor complexes has been reported in the amygdala, hippocampus, and medulla regions of rat brain.

65 Based on in vitro and in vivo binding studies in rats revealing that the resin and pyrones had only weak binding effects on benzodiazepine receptors, Davies et al.

66 concluded that the pharmacological activities produced by kava pyrones are not due to a direct effect on GABA receptors.

Extract WS 1490, with 70% kava-pyrone content, was tested in a double-blind placebo-controlled study in patients with various DSM-III-R anxiety disorders of nonpsychotic origin.

67 (A limitation of the study was a diagnostically heterogeneous sample of patients with anxiety disorders and comorbid depression.) Patients reported significant improvement in anxiety symptoms as measured on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale from week 8 through week 24 in the kava group relative to placebo. The dose administered was 70 mg of 70% kava-lactones (synonymous with pyrones) by mouth three times a day.

52 Suggested dosages are 150–200 mg (30% kava-lactones) po 1 to 3 times a day for anxiety and 500 mg po at bedtime for insomnia. More reliable doses are becoming available in the United States as the variety of OTC preparations increases.

Side effects reported in kava studies include stomach upset, vertigo, and a yellow, scaly rash at high doses. Elevations in liver enzymes, decreased albumin and protein, and increased cholesterol also have been noted.

68 Adverse effects reported include orolingual dyskinesias and torticollis, when kava was taken alone,

69 and lethargy and disorientation when the herb has been used in combination with a benzodiazepine.

70Ginseng (Panax ginseng, P. quinquefolius, and Eleutherococcus senticosus)

This Asian folk medicine has been used for thousands of years as a tonic for the restoration of strength and as a panacea for general healing. The dried root of Asian (

Panax) ginseng contains at least 13 different ginseng saponins, called ginsenosides. The Siberian (

Eleutherococcus) species is distinct from the Chinese in that it contains eleutherosides, or aglycon glycosides, which are completely different in chemical structure from the ginsenosides. Ginseng has been touted as an “adaptogen”—defined as a substance that increases resistance to biological, chemical, and physical stress—and as a product that improves vitality, including physical and mental work capacity. The root has been associated anecdotally with mood enhancement and improved quality of life. There is a lack of controlled data to suggest performance enhancement in fatigued humans.

71Preparations of the root can be administered orally, intranasally, or parenterally. Ginsenosides, the active ingredients, contain triterpenoid saponin glycosides. Central cholinergic and variable dopaminergic

72 system effects, as well as stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, have been proposed.

73 Ginseng appears to facilitate acetylcholine release and is associated with increased uptake of choline into hippocampal nerve endings.

74 Ginseng reportedly has no effect on acetylcholinesterase or muscarinic receptor binding activity.

75The ginsenoside Rg1 exerts a “life-prolonging effect” on chick and rat cerebral cortex neurons in cell cultures as compared to nerve growth factor.

76 Animal studies of ginseng describe stimulation of protein synthesis, inhibition of platelet aggregation, increased immune system activity, prevention of stress-induced ulcer, and anticonvulsive effects,

77 but human data are lacking.

Few controlled clinical studies of ginseng have been reported. The ergogenic properties of the root concentrate were tested in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study, showing no effect on work performance or associated physiologic or psychologic measures.

78 Cognitive functions were assessed in a study of 112 healthy volunteers, revealing no significant differences between ginseng and placebo group assessments of concentration, memory, or subjective experience.

79The usual recommended daily dose of ginseng dry root is 0.5 to 2.0 g. Capsules containing 250 mg of the root are commercially available. Concern has arisen regarding the content purity of commercial preparations of ginseng, as noted above.

Ginseng may have adverse interactions with psychoactive drugs and other drugs. The induction of manic-like symptoms was seen in a 42-year-old depressed woman taking ginseng concurrently with phenelzine.

80 A 63-year-old man with membranous glomerulonephritis developed edema and hypertension after adding Korean ginseng (a germanium-containing ginseng product) to his regimen of furosemide and cyclosporine.

81 Other case reports include decreased International Normalized Ratio (INR) in a patient on warfarin

82 and elevated digoxin serum concentrations without signs of toxic effects in a 74-year-old man.

83 With respect to the above case reports, the use of ginseng with cardiovascular medications should be discouraged. It is unknown whether ginseng interacts with the P450 enzyme system.

Adverse effects include the development of a manic state after initiation of one ginseng tablet per day for 10 days in a previously depressed 35-year-old woman.

84 CNS stimulant activity (“irritable, uncooperative…, and overactive with disturbed sleep”) was reported in a patient with schizophrenia without worsening psychotic symptomatology.

73 Ginseng was implicated as having induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome in a 27-year-old man.

85 Cerebral arteritis was noted in a case report in a 28-year-old woman after ingestion of a large quantity of ethanol-extracted ginseng.

86 “Ginseng abuse syndrome” has been described, characterized by nervousness, hypertension, sleeplessness, morning diarrhea, and skin eruptions in “chronic” root users taking 3 grams per day for at least 1 to 3 weeks.

87Valerian (Valeriana officinalis)

Valerian comes from the herbaceous perennial plant

Valerian officinalis, which grows throughout North America, Europe, and Asia. This root is used as a sedative and hypnotic. Other proposed indications include anxiety and epilepsy; these applications have yet to be validated in humans. The rhizome of valerian contains two pharmacologically active ingredients: valepotriates and sesquiterpenes (valerenic acid and acetoxyvalerenic acid). Sedating effects of the active agents have been demonstrated in mice.

88 The general pharmacological properties of these agents are unknown. Valerian crude extract, however, is noted to have GABA

B receptor binding properties.

9 Valerian extract also demonstrates GABA uptake inhibition in rat synaptosomes.

89 Although the valepotriates are cytotoxic in cell culture, this has not been observed clinically.

90A placebo-controlled study tested the ability of valerian to decrease sleep latency and night awakenings and to improve sleep quality in 128 subjects without documented sleep disorder diagnoses.

91 Although objective measures of sleep were unaffected by valerian, it produced a significant decrease in self-rated sleep latency scores and a significant improvement in self-reported sleep quality in habitually poor sleepers. In a separate double-blind placebo-controlled parallel-group-design study with 14 elderly female poor sleepers, Schulz et al.

92 demonstrated an increase in slow wave sleep, without REM alteration, in a valerian-treated group of 8 subjects versus a placebo group of 6.

Valerian doses range from 500 mg to 12 g,

90 given either in three divided doses or once nightly. No drug interactions or acute side effects from valerian have been reported in normal, limited dosing.

One case report, from Willey et al.,

93 describes a valerian overdose in a woman who took 20 times (approximately 20 g) the recommended dose. Adverse effects included fatigue, abdominal pain, chest tightness, tremor of hands and feet, and lightheadedness. These symptoms resolved within 24 hours of ingestion. Adverse reactions reported by some chronic users included headaches, excitability, uneasiness, and cardiac disturbances.

Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium)

Today, feverfew is generally used for migraine headache prophylaxis. The leaves of this bushy perennial contain parthenolide, a sesquiterpene lactone that inhibits platelet 5-HT release.

94 An extract of feverfew has also been reported to inhibit prostaglandin (PG) biosynthesis via a mechanism that differs from salicylates, in that the extract did not inhibit cyclo-oxygenation by PG synthase.

95 This action may explain the historical use of this plant as an antipyretic.

A pilot study to profile adverse effects and to establish the efficacy of feverfew in a sample of patients who had formerly used feverfew leaves daily showed a significant increase in the frequency and severity of headaches in former users taking placebo.

96 This study was followed by an 8-month prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study of 72 migraineurs. The frequency of migraines was significantly decreased in subjects taking feverfew. Among the 60 patients who completed the study, 35 subjects (59%) in the crossover arm reported fewer headaches with feverfew during the 4-month treatment period. Subjects who had never taken feverfew in the past reported a 23% reduction in the number of attacks and in the severity of associated symptoms.

97In the United Kingdom the usual prescribed dosage is 50 to 100 mg daily, and the product is sold as dried leaves, capsules, concentrated drops, tinctures, and extracts. Chronic users report eating one to four small fresh leaves daily for migraine prophylaxis, usually with food to mask the bitter flavor of the plant. Manufacturers recommend daily doses of herb capsules varying from 600 to 1,800 mg in divided doses; however, 0.25 mg (250 μg) of parthenolide daily has been shown to be adequate for migraine prevention.

Chewing the leaves has been associated with ulcers of the mouth in 11% of subjects, with a reversible tongue irritation and lip swelling in these patients.

96Although a sublingual spray is available, the exact amount of the substance delivered in the spray is not known. The potency of this product is variable across manufacturers.

Garlic (Allium sativum)

Garlic is thought to have anti-atherosclerotic properties. Studies in humans and in animals have demonstrated lowered lipid levels, blood pressure, plasma viscosity, and inhibition of platelet aggregation.

98 Garlic exerts its hypolipemic effect through the active ingredient, allicin, a sulfur-containing amino acid compound. The mechanism of action is unknown; however, hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibition

99 and remodeling of plasma lipoproteins and cell membranes

100 have been proposed.

In a 12-week double-blind placebo-controlled study of 900 mg of garlic powder tablets, significantly lower total cholesterol and low-density lipoproteins (LDL) were reported in the treatment group.

101 Side effects were limited to eructation (belching), and there were no significant odor problems. A German meta-analysis found that garlic reduced hypercholesterolemia by 5% to 20%.

102 An American meta-analysis of five randomized placebo-controlled trials, incorporating patients with total cholesterol exceeding 200 mg/dl, revealed a pooled result of a 23 mg/dl drop in 164 patients treated with 600 to 1,000 mg garlic per day.

103The common dose ranges prescribed are 0.6 g to 0.9 g garlic powder daily. The GCEm reported the average dose to be 4 g fresh garlic daily.

13 Dried garlic contains no allicin. Rather, it contains the precursor, alliin, and the alliinase enzyme necessary to convert alliin to allicin. Studies noted above recommend a dried garlic powder preparation standardized to 1.3% alliin for effective cholesterol and triglyceride reduction. Manufacturers' variability again brought concern regarding potency of the preparations after a German study revealed only 5 of 18 garlic supplements contained acceptable amounts of allicin.

There are no known drug interactions with garlic; however, it should be used cautiously in patients receiving anticoagulants because of a potential bleeding risk.

Uncommon side effects of garlic include gastrointestinal disturbance, asthma, contact dermatitis, and foul odor. Enteric coated dried garlic minimizes garlic taste and odor. Adverse effects include a case report of spinal hematoma in an 87-year-old man, attributed to the antiplatelet effect of excessive garlic ingestion.

104Yohimbine (Corynanthe yohimbine)

This medication is discussed because of its transformation from initial consideration as an herbal alternative medicine to mainstream acceptance as pharmacological therapy.

Yohimbine comes from the trunk of

Pausinystalia yohimbe, a Central African tree of the Rubiaceae family. The substance has been reputed to be an aphrodisiac since the early part of this century.

105 The bark contains indole alkaloids and acts as a treatment for male impotence and for orthostatic hypotension.

A review of seven double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials was conducted and revealed that yohimbine is superior to placebo in the treatment of organic and psychogenic erectile dysfunction, with a range of positive response from 34% to 73%. Dosages ranged from a total of 16.2 to 30 mg per day in three divided doses. Although yohimbine is probably less effective than vasoactive intracavernous injection therapy, it is considerably less invasive.

106 Reid et al.

107 found a 46% partial or full response to yohimbine in a 10-week double-blind placebo-controlled partial crossover trial with 48 subjects having psychogenic impotence, and recommended that the drug be considered among first-line treatment options in the psychogenically impotent patient. Finally, clinical benefit has been reported from using lower doses of yohimbine in sexual dysfunction induced by clomipramine and fluoxetine.

108 No information is yet available on comparing yohimbine with the newer agent sildenafil (Viagra).

Pharmacologically, yohimbine acts as a presynaptic α-2 adrenoreceptor antagonist. Alpha-adrenolytic drugs produce a rise in sympathetic drive by increasing noradrenaline turnover and central nervous system noradrenergic nuclei cellular firing rate.

109,110 Other pharmacologic properties of yohimbine include dopamine receptor antagonism, MAO and cholinesterase inhibition, and 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor antagonist and agonist activity.

111 The drug is not eliminated in the urine and is thought to be metabolized with rapid plasma clearance, demonstrating a biological t½ of 36 minutes.

112,113 Morales et al.

114 observed a 2- to 3-week latency between onset of daily yohimbine administration and erectile function improvement.

The GCEm recommend that the bark should not be taken by patients with renal disease, noting increases in blood pressure. Yohimbine is not recommended for use in patients with cardiac history or a history of gastrointestinal ulcer.

13 Mild antidiuretic activity may be present from stimulation of antidiuretic hormone release. Side effects include mild anxiety and panic attacks.

115 Treatment with yohimbine is advised with caution in patients taking psychotropic medications because of its potential effects on cholinergic and adrenergic activity.

116Adverse effects include the precipitation of transient, manic-like symptoms in depressed patients with a bipolar diathesis.

117 Increased cholinergic and decreased adrenergic activity associated with yohimbine have also been implicated in increased mucous secretion and bronchoconstriction-induced bronchospasm.

118 An idiosyncratic lupus-like syndrome has also been reported in a 42-year-old man.

119 Direct autonomic effects from injected yohimbine include increased systolic blood pressure; increased anxiety; tachycardia; increased perspiration, salivation, lacrimation, and pupillary dilation; nausea; urgency; and erection.

120Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea and E. pallida)

Derived from the common purple cone flower, echinacea is one of the most popular supplements sold in the United States. Native Americans originally used the plant to treat respiratory infections. Extracts and preparations are derived from the leaves and flowers of the

purpurea species and from the root of the

pallida species.

121 Given its widespread use for putative immune-stimulating effects, echinacea is referenced because of possible contraindications in immune-related neuropsychiatric illnesses such as multiple sclerosis (MS), HIV infection, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Echinacea has not been studied largely in the neuropsychiatric population. One study reported that of 129 patients with documented MS, 63% used 87 different AT and approximately 40% (

n=32) used herbs for treatment of their illness. With echinacea being one of the five best selling HAMs in the United States, it is likely that some form of the preparation is being taken by these MS patients whose aim is “to participate actively in the healing process.”

122Studies have shown that the active ingredients in echinacea are isobutyl amides, caffeic acid derivatives, and heteroxylan, a high-molecular-weight polysaccharide. The actions noted from human in vitro studies include increasing the number of leukocytes, activating granulocytes, increasing phagocytosis by heteroxylan, inhibiting hyaluronidase, and stimulating tumor necrosis factor release by arabinogalactan.

123The GCEm recommend that patients with autoimmune diseases, such as MS, should not take the medicine because of its immunostimulant property. Administration of echinacea in AIDS has also been discouraged by the GCEm because of concern for impairment of T-cell functioning. There are no studies in vivo of this herb in immunodeficiency diseases such as HIV infection, although enhanced natural killer cell activity has been reported in vitro with echinacea in AIDS and chronic fatigue syndrome.

124