Apathy is best conceptualized as a lack of motivation revealed in diminished evidence of goal-directed behavior, including deficits in initiative, persistence, planning, and monitoring.

5 Such motivational difficulties are likely to interfere with activities of daily living (ADLs). Apathy,

6 depressive symptoms,

7 and other behavioral disturbances (e.g., behavioral retardation, blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, and low motivation)

8 are unrelated to the severity of dementia and cognitive dysfunction in VaD patients. Therefore, apathy and other behavioral disturbances should provide unique information in predicting the functional abilities of VaD patients.

Associations have been previously reported between behavioral disturbance and basic ADLs (BADLs), such as toileting and hygiene,

15 and instrumental ADLs (IADLs), such as managing medications and finances.

16 Behavioral disturbance or inability to regulate purposeful, goal-directed behaviors were more predictive of ADL status than mental status. Apathy

17 and depression

9,18 have been shown to contribute significantly to prediction of ADL status. However, apathy and depression are distinct disturbances.

3,5The purpose of the present study was to investigate the extent to which both cognitive and behavioral dysfunctions are associated with functional impairment in VaD patients. We hypothesized that apathy would contribute significantly to total functional disability beyond the severity of cognitive impairment. In addition, we hypothesized that as ADLs increased in complexity and cognitive demand, degree of cognitive dysfunction would contribute more to the patients' ability to complete these tasks independently.

METHODS

Participants

Baseline data were obtained from 29 caregivers and individuals who participated in a 12-month double-blind placebo-controlled trial of citicoline for the treatment of VaD. A neurologist (N.G.) conducted comprehensive neurological and medical evaluations to confirm the diagnosis of VaD, according to both the NINDS-AIRENS

19 and the DSM-IV criteria.

20 Inclusion criteria required age greater than 54 years and a score between 9 and 24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

21 Patients with terminal systemic disease or neurological disorder deemed unrelated to VaD (including degenerative diseases), history of significant head injury or major psychiatric disorder (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) or current evidence of substance abuse or psychiatric illness were excluded. Exclusion criteria also included meeting DSM-IV

20 or NINCDS-ADRDA

22 criteria for Alzheimer's disease, and significant atrophy of the mesial temporal lobe evident on MRI. For the present study, patients also were excluded if ADL

23 or Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe)

24,25 data were missing. More than 1,000 individuals were screened to participate in this study from university-affiliated memory disorders clinics, neurology clinics, and regional nursing homes. Therefore, the patients that met the above criteria represent a relatively homogeneous group. Individuals were not compensated for participation. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or a legal guardian following a thorough explanation of the study.

The present study is based on the baseline functioning data obtained prior to placebo or drug administration. Twenty-nine patients had complete baseline data for purposes of the current study and were therefore selected from the original larger set of the 39 participants who were involved in the drug trial. Our study sample averaged 78.2 years of age (SD=5.53, range 67–87), 11.8 years of education (SD=3.34, range=6–20) and 20.4 points on the MMSE (SD=3.64, range 11–24), and consisted of 16 men and 23 women. All individuals exhibited subcortical hyperintensities to at least a moderate degree, consistent with subcortical small vessel disease. None of the patients evidenced obvious hippocampal atrophy on neuroimaging. In addition, MRI scans indicated cortical stroke in 3 patients and subcortical stroke in 7 patients (4 basal ganglia, 1 thalamic, and 2 thalamic and basal ganglia stroke). Four patients had evidence of mixed cortical-subcortical stroke (3 patients with cortical and basal ganglia stroke, 1 patient with cortical and thalamic stroke).

Procedures

All data were collected as part of a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation prior to the initiation of drug/placebo. All tests were administered in a single day, with rest breaks provided as needed. MRIs were performed on the day following the neuropsychological examination. Information on behavioral disturbance and activities of daily living was obtained from a primary caregiver on the day of the initial neuropsychological evaluation. All tests were administered and scored according to standard procedures.

The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS)

26 was administered as a measure of general cognitive abilities. The DRS is a common screening measure used to identify and monitor the severity of dementia. The DRS examines cognitive functions across five domain subscales that include attention, initiation/perseveration, conceptualization, memory, and construction. The total number of correct responses summed across the five subscales was used for this study.

The modified version of the Lawton Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Physical Maintenance Scale

23 was employed. This caregiver questionnaire is a 14-item scale that includes 8 questions pertaining to instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs; e.g., ability to manage medications and finances) and 6 questions pertaining to basic activities of self-care (BADLs; e.g., toileting, grooming). Each question was scored according to the individual's ability to complete each activity independently (0=independent, 1=some assistance required, 2=complete dependence on others for completion of the task). Thus, higher scores indicate greater impairment on ADLs. Missing data points were replaced with the average score obtained within the particular subscale. Only 2 patients had a data point that was missing.

The Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe),

24,25 a brief, reliable behavior rating scale designed to specifically measure behaviors subserved by frontal systems, was used to examine behavioral disturbances in VaD. The FrSBe-Family version was completed by a family member, rating the relative frequency of behaviors related to three frontal behavioral syndromes. The scale yields a total score indicating the overall presence of “frontal” behavior and three subscale scores related to three specific frontal systems behavioral syndromes (Apathy, Disinhibition, and Executive Dysfunction). Higher ratings reflect a greater degree of abnormality.

The FrSBe has been shown to have a high degree of split half reliability in dementia and frontal lesion groups, and validity for measuring behaviors associated with frontal systems dysfunction has been established.

23 It has been shown to be a sensitive measure of behavior in cortical and subcortical dementia, and meaningful relationships have been found between the FrSBe and neuropsychological measures and activities of daily living.

27Although none of our participants met criteria for major depression, we conducted semistructured clinical interviews with each caregiver and patient to determine if mood disturbance existed in our sample. In these interviews, 25 patients and their caregivers did not endorse depression symptomatology, 1 patient and caregiver reported occasional depressed mood, 2 patients endorsed occasional depressed mood but their caregivers reported no depression symptoms, and 1 patient endorsed some depression symptoms while the caregiver did not endorse any observed depression symptoms.

Statistical Analyses

All data analyses were performed with SPSS software. A series of stepwise linear regression analyses were conducted on predictor variables in order to examine the variance accounted for by the studied variables in ADLs. Stepwise regressions were selected to examine the entry and removal of variables in the block at each step. The predictor variables were total DRS score and three FrSBe subscale scores (Apathy, Disinhibition, Executive Dysfunction). Separate linear regressions were conducted for the three dependent variables (total ADLs, BADLs, IADLs). Descriptive statistics were calculated on patient demographic variables, DRS, ADLs, and FrSBe scores. We also conducted t-tests to examine potential differences in the above predictor variables (Apathy, Disinhibition, Executive, and DRS total scores) between the patients with MRI-identified stroke (n=14) and patients with subcortical hyperintensities only (n=15).

RESULTS

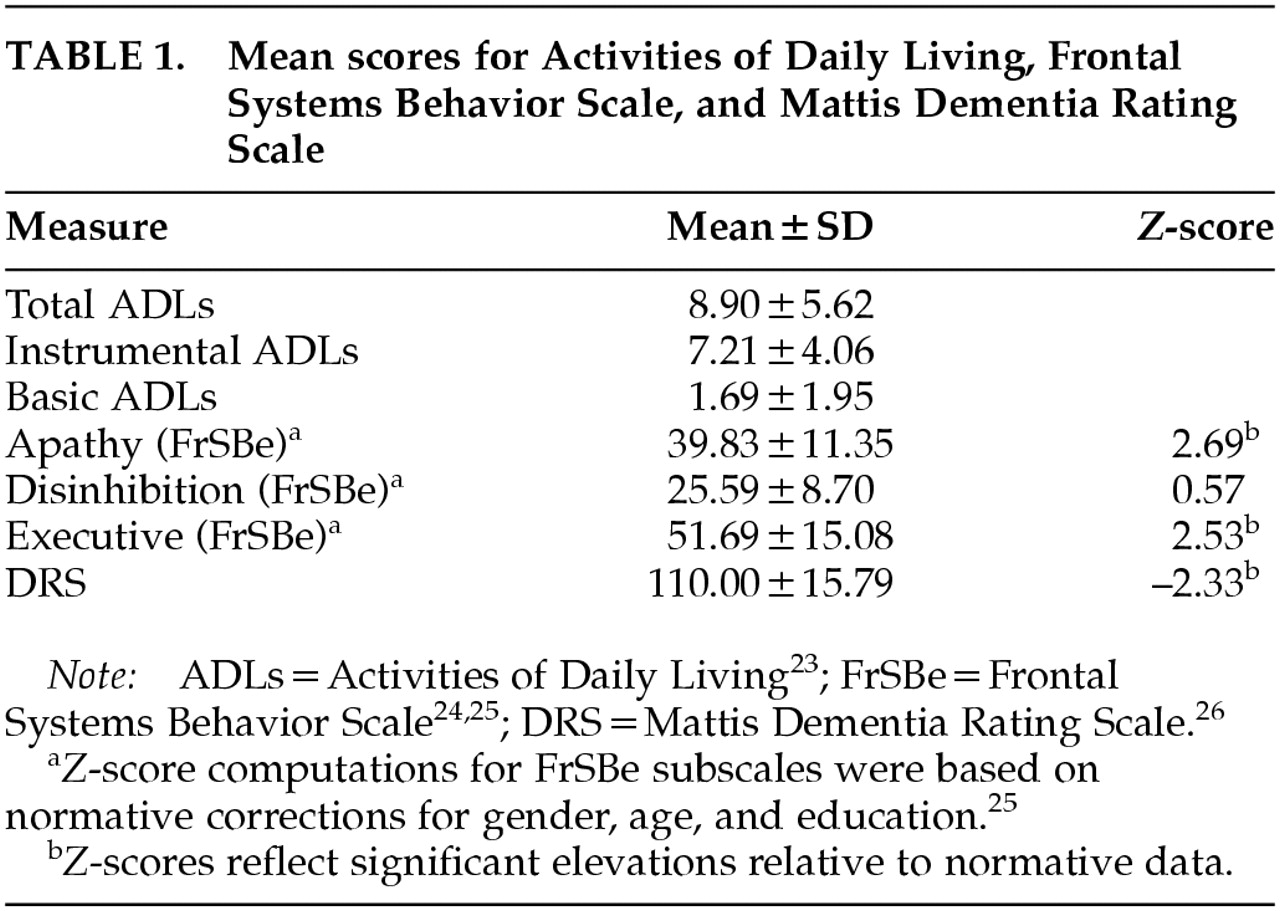

Mean scores for ADLs (IADL, BADL, and total), FrSBe (Apathy, Disinhibition, Executive), and DRS are presented in

Table 1. The average DRS performance was 110 (SD=15.79), which is below the recommended cutoff of 123 for dementia.

Z-scores based on gender, age, and education normative corrections were computed for FrSBe subscales.

26 Significant elevations, of at least 2.5 standard deviations above the mean, were found on the FrSBe Apathy and Executive subscales, whereas the mean Disinhibition score was within normal limits.

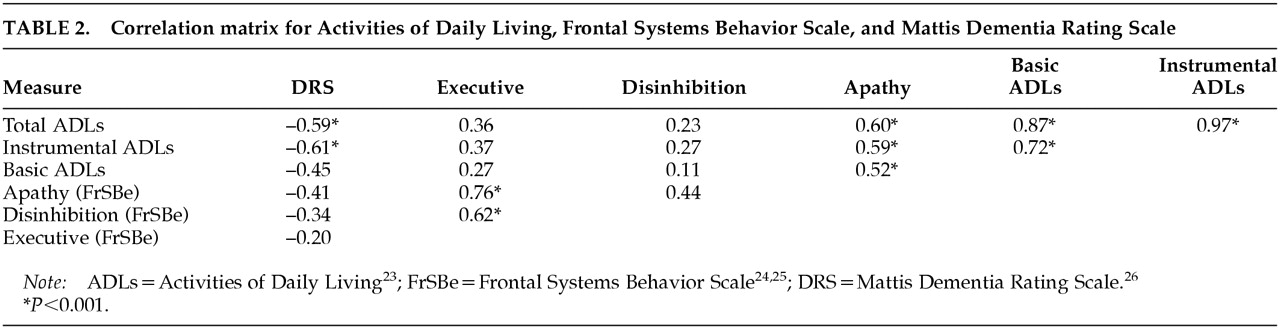

Table 2 illustrates the correlation matrix between these variables. Strong associations were found between ADLs and DRS as well as ADLs and apathy. Significant associations were not found between DRS and FrSBe behavioral scores or between ADLs and FrSBe behavioral scores of Executive Dysfunction or Disinhibition. Therefore, although the FrSBe Executive Dysfunction score was significantly elevated in this VaD sample, it was not significantly associated with ADLs or dementia severity (DRS).

The initial stepwise linear regression analysis revealed that the FrSBe Apathy subscale and DRS total were significantly related to total ADLs (R=0.71, F=13.44, df=2,28, P<0.001), and these scores accounted for approximately 51% of the variance in ADLs. Apathy accounted for 36% of the variance in ADLs, and total DRS score accounted for an additional 15% of the variance.

To examine the contribution of these variables to the prediction of basic and instrumental ADLs specifically, we then conducted two additional stepwise linear regressions to examine the variance accounted for by the three FrSBe subscale scores (Apathy, Disinhibition, Executive) and the total DRS score. With regard to IADLs, the stepwise linear regression analysis revealed that the DRS total score and the Apathy subscale were significantly related to IADLs (R=0.71, F=13.43, df=2,28, P<0.001). In results similar to the initial regression, DRS total and Apathy accounted for approximately 51% of the variance in IADLs. In this analysis the DRS score accounted for approximately 37% of the variance in IADLs and Apathy accounted for an additional 14% of the variance.

The final stepwise linear regression analysis revealed that the Apathy subscale was the only predictor of BADLs (R=0.52, F=9.88, df=1,28, P=0.004). Apathy accounted for approximately 27% of the variance in BADLs. It is noteworthy that DRS total and the Disinhibition and Executive subscales of the FrSBe did not add significantly to the prediction of BADLs.

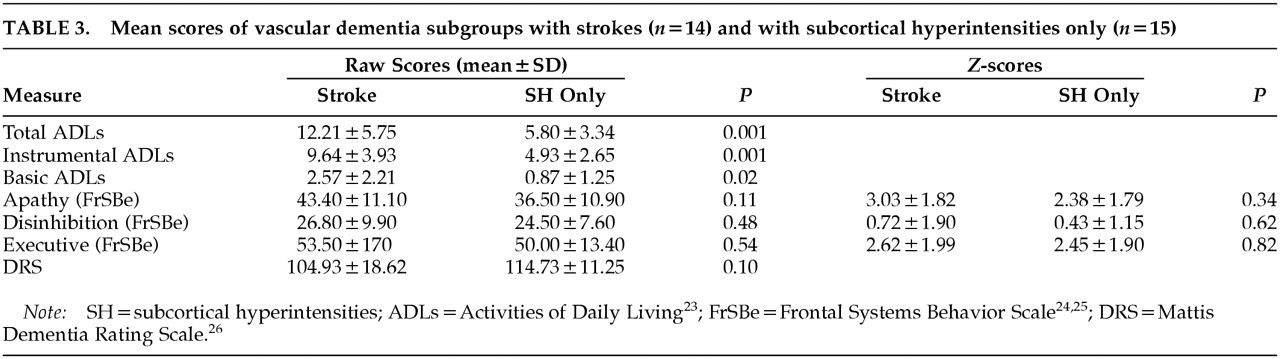

We also compared VaD patients having MRI-identified strokes (

n=14) with VaD patients having subcortical hyperintensities only (

n=15) on the above predictor variables. None of the variables (DRS, Apathy, Executive, Disinhibition) were significantly different between the groups. However, in the stroke group there were trends toward lower DRS scores (

t=–1.73, df=27,

P=0.10) and more observed apathy (

t=–1.67, df=27,

P=0.11). In addition, the stroke group had significantly more difficulty with basic, instrumental, and total ADLs (Basic:

t=–2.58, df=27,

P=0.02; Instrumental:

t=–3.80, df=27,

P=0.001; Total:

t=–3.70, df=27,

P=0.001). Data are provided for each VaD subgroup in

Table 3.

In the stroke group alone, the stepwise linear regression analysis revealed that DRS total score was significantly related to total ADLs (R=0.66, F=9.00, df=1,13, P<0.01), accounting for 43% of the variance in total ADLs. Apathy was significantly related to IADLs (R=0.71, F=12,29, df=1,13, P<0.01), accounting for 51% of the variance in IADLs. None of the predictor variables were significantly associated with BADLs.

In contrast, the subcortical hyperintensity–only group did not have any predictor variables significantly associated with IADLs or total ADLs. However, the BADLs were significantly associated with the FrSBe Executive subscale (R=0.67, F=10.76, df=1,14, P<0.01). Executive dysfunction accounted for 45% of the variance. Thus, it appears that the subgroup of VaD patients with strokes may be accounting for the relationships of increased apathy and decreased DRS with ADLs. It also appears that the two subgroups have significantly elevated levels of apathy and executive dysfunction but that the relationships of these behavioral syndromes with ADLs are different.

DISCUSSION

The strong association between apathy and patients' abilities to complete basic ADLs and instrumental ADLs is evident in our sample of VaD patients. These findings are not surprising given the initiation and motivation necessary to complete either type of activity. Apathy contributes above and beyond dementia severity in BADLs. In this VaD sample general cognitive ability was not a significant predictor of BADLs (e.g., hygiene), which is consistent with a previous study of patient's with Parkinson's disease.

13Caregivers' observation of apathy is predictive of patients' need for assistance with ADLs. The significance of apathy is underscored by the amount of unique association of apathy with basic and overall functional abilities of VaD patients. These findings are consistent with reports of population-based, normal elderly individuals without cerebrovascular disease or severe motor impairment who demonstrated a similar relationship between apathy and ability to perform ADLs.

17Behavioral disturbance in demented patients and normal aging individuals has been hypothesized to be more predictive of functional dependence than are general cognitive abilities.

10,28 It was suggested that this dissociation is primarily a function of different degrees of loss of capacity to engage in purposeful, goal-directed activity and declining executive abilities,

10 which is consistent with apathy or disorders of initiation and lack of motivation. However, goal-directed activity has many elements, such as identifying a goal and sequencing, that could be affected. For this reason, observation and behavioral analysis of each patient's ability to initiate and complete the various components of ADL tasks would be beneficial to understanding the specific difficulties that affect the breakdown in ADL functions.

It is possible that the associations observed between apathy and ADLs in the present study are simply a function of the manner in which each is measured and the possible overlapping features of the various constructs. Behavioral analysis of ADL performance would be helpful in examining this issue and the related issue of sensitivity of the measures. Future studies should explore performance on specific executive tasks that may be more strongly associated with and contributory to these behavioral impairments. For example, the attentional disturbance and psychomotor slowing previously described in our sample of VaD patients

29 may affect their ability to perform different ADL tasks.

As hypothesized, general cognitive impairments become a more critical factor in predicting the demanding and complex tasks of instrumental ADLs. IADLs require more advanced cognitive abilities, including intact executive functions such as planning and organization, for performance of tasks such as managing finances or administering medications. We know from our laboratory's previous study of executive abilities in this VaD sample

29 that their neuropsychological performance is impaired. This pattern of performance is consistent with our current finding of caregivers' observation and endorsement of impaired executive behaviors (FrSBe). However, it is surprising that we did not find a significant relationship between the FrSBe executive dysfunction subscale and IADLs, given that the executive subscale score was significantly elevated. The lack of relationship between perceived executive behavioral problems and ADLs in these VaD patients may be due to the moderate level of dementia present in this small sample. Changes in behavioral profiles with disease progression have been found in Alzheimer's disease, with apathy prominent in the early stages and problems with disinhibition and greater executive dysfunction in the later stages.

30 It may be that behavior associated with moderate VaD is primarily apathetic. Future studies should examine behavioral profiles in moderate to severe VaD to identify potential differences in problems as the disease progresses.

The present results should be interpreted cautiously. Clinically differentiating VaD and AD without neuropathological data is a challenge to dementia researchers.

31,32 We also have a relatively small sample size for this study. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that the BADLs were not severely impaired across our sample. It appears, however, that some loss of BADL independence was associated with significantly elevated level of apathy. Disruption of IADLs was endorsed more frequently in our sample than difficulty with BADLs, and there was no evidence of floor or ceiling effects on this measure. The present study presents important associations; however, causal relationships between these variables cannot be assumed. Future studies should examine longitudinal and other experimental data in order to better understand the relationships between apathy, dementia severity, and ADLs.

Furthermore, VaD patients tend to have significant disease burden and physical disability. Patients with cerebrovascular disease often have serious medical comorbidities and disabilities such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke that contribute to the development of the cerebrovascular disease. It is possible that the significant disease burden of these illnesses also contributes to the level of apathy evident in this sample, independent of the CNS involvement. It will be important for future studies to examine these specific relationships, possibly in patients with diabetes and heart disease, prior to the development of cerebrovascular disease.

Trends of increased apathy and decreased DRS ratings were evidenced in VaD patients with MRI-detected strokes compared with VaD patients having subcortical hyperintensities only. The current findings suggest that VaD patients with strokes may account for the relationship of increased apathy and decreased DRS with ADLs. In addition, the VaD patients with strokes had significantly more impairments in ADLs compared with the subcortical hyperintensity–only group. Comparison of these VaD subgroup data suggests that there may be different patterns of relationships between frontal behavioral syndromes, general cognitive impairment, and ADLs. Therefore, level of disability and evidence of stroke will be important variables to consider in future research.

Assessment of frontal behavioral syndromes in vascular dementia patients has clinical importance. Apathy and executive dysfunction, as reported by caregivers in the present study, were significantly elevated in both VaD subgroups: stroke patients and those with subcortical hyperintensity only. People with limited capacity to regulate their behavior independently are likely to have significant functional impairments. Further studies are needed to find effective interventions that address elevated levels of apathy in VaD patients and that may subsequently improve their functional abilities. Environmental modifications that provide structure and cueing may be beneficial for improving independent functioning in individuals with apathy, both those who are healthy and those with dementia.

10,11 Likewise, evaluation of pharmacological interventions

33,34 may provide an avenue to improved function in patients with VaD.