PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

A 77-year-old right-handed man presented for neurological evaluation after 4 years of progressive decline in his ability to use language. This decline began insidiously with progressively worsening word-finding difficulty and naming impairment. Over the course of 2 years, the anomia progressed to severe difficulty with spoken language. He presented to two physicians, who documented an anomic aphasia, a partial response to phonemic cues, and relatively preserved memory and other cognitive functions. About 3 years into this course of illness, the patient developed difficulty with auditory comprehension and writing. He also began to have memory difficulty and visuospatial problems, including impairment in dressing. The patient's medical history was positive for depression, which had been treated with fluoxetine, and his family history was positive for dementia, in his mother. The patient was a college graduate and a former businessman, and he smoked one to two cigars daily and drank 2 ounces of wine nightly.

In the neurological evaluation, initial cognitive testing revealed fluent but anomic language. The patient's verbal output was not effortful, agrammatic, dysarthric, or dysprosodic. The content was impoverished, however, and he had a circumlocutory tendency and mild echolalia. For instance, when asked to name a pen, the patient replied, “a unit to …” but could not find the word. He sometimes produced semantic and mixed paraphasic errors, giving “point … plank” for pen, “pop” for a watch, “sheet” for shoe, and “twice” for second floor. In contrast, he was able to point to colors, pictures, and body parts—with the exception of fingers—appropriately when given the names. Auditory comprehension was impaired, and he demonstrated comprehension of only 70% of yes-no questions. Repetition was impaired by paraphasic errors. The patient had ideomotor apraxia (worse on the left) on both command and imitation. Although memory difficulty was evident, neither verbal nor visual memory could be tested in detail because of the severity of the aphasia. The patient had mild visuospatial deficits. Finally, he had prominent difficulty with calculations, out of proportion to his aphasia.

During the next 2 years the patient had a gradual, progressive dissolution of both speech and language and worsening memory and visuospatial function. He developed stuttering and palilalia. His verbal output was otherwise fluent but remarkably empty, with frequent paraphasic errors. Such errors occurred even when he attempted to say his first name, Paul, for which he produced “Parma,” and later “Pisel.” The paraphasic errors were more often phonemic than semantic. Repetition, reading, and writing were extremely impaired. Language comprehension was markedly abnormal, with an inability to understand single words or single-step commands. The severe language disturbances interfered with cognitive testing in other domains, but he failed visual memory and visual construction tasks. Praxis, which was impaired on imitation as well as on command, worsened to the point that the patient had difficulty shaking hands and frequently dropped things. He developed spontaneous generalized myoclonic jerking, which occurred in the mornings. The jerking was suppressed by a low dose of oral clonazepam. The remainder of the physical and neurological examination was normal.

The patient underwent laboratory evaluation and neuroimaging. Routine laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient's apolipoprotein E genotype result was ε3/ε3. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed by the referring physician was reportedly unremarkable. An attempt was made to repeat the MRI, but the patient was not able to cooperate. In addition, the patient underwent two single photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) scans. The first SPECT scan revealed severe perfusion defects involving the left frontal, temporal, and parietal regions. The second SPECT scan (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), performed 2 years later, revealed worsening of perfusion defects in the posterior temporal and right dorsal posterior parietal areas.

During the next year the patient's behavior continued to worsen. He became agitated and angry without evident provocation, sometimes shaking his finger to scold strangers in the grocery store or screaming at cars passing by. Seeing his own reflection in the mirror triggered some of his bouts of agitation. He seemed not to recognize himself and would begin shouting at the mirror. Eventually this led his wife to cover the mirrors to avert the episodes. He also seemed to misidentify his daughter and caregiver and was hostile toward them, once hitting his caregiver.

The patient's speech and language remained prominently impaired. His fluency deteriorated, and he developed constant palilalia and logoclonia when attempting to speak. At his final clinic visit his caregiver reported that he was capable of only one apparently meaningful utterance: “I'm going to die.” Apart from this he was unable to communicate or demonstrate any capacity for comprehension. He was noted to have periods of extreme agitation during which he would clap his hands and make repetitive vocalizations that culminated in outright yelling for several minutes. On his last examination he was limited to prominent acquired stuttering, often getting stuck on the initial syllable of a word and repeating it over and over in an explosive manner. Two clinicians who saw him late in the course of his illness noted infrequent myoclonic jerks of the right arm that occurred spontaneously or with intention, but not in response to startle. Some of the agitation the patient experienced during the last several months of his life improved with treatment with risperidone. A few months later he died in his home of pneumonia.

In sum, our patient had a progressive aphasia that began with involvement of the temporoparietal cortex in the dominant hemisphere but progressed to a reiterative speech disorder and global dementia.

CLINICAL DISCUSSION

Progressive fluent aphasia was this patient's sole or predominant deficit during the first few years of his illness. Aphasia usually results from lesions that involve the perisylvian cortex of the language-dominant hemisphere. This patient also developed early ideomotor apraxia, myoclonus, and acalculia. Ideomotor apraxia (for both pantomime and imitation) and acalculia are associated with lesions of the dominant hemisphere, typically in the region of the inferior gyrus of the parietal lobe. Earlier, this patient had suffered from a dressing disturbance. Dressing apraxia is a deficit of mapping parts of clothing onto the body surface and can result from a lesion of the parietal lobe in the nondominant hemisphere. In this patient the source of the dressing disturbance could have been the ideomotor apraxia. Myoclonus of the right arm suggests the presence of irritation in the motor cortex of the left frontal lobe resulting from epilepsy, hypoxia, or a neurodegenerative disease. Eventually the patient developed profound amnesia. Amnestic disorders result from damage to limbic and mesial temporal lobe structures, especially those included in the Papez circuit: the hippocampi, fornices, mammillary bodies, anterior thalamic nuclei, posterior cingulate gyrus, and the connections among these structures.

Aphasia was the earliest and most salient feature of this patient's illness. The most common causes of aphasia are vascular lesions, especially ischemic stroke, and trauma. In the case of vascular disturbances, the onset is typically sudden, usually followed by gradual improvement and sometimes complete recovery. This patient had no history of head trauma, which can result in the sudden onset of aphasia but with a somewhat better prognosis than that due to stroke. These courses of aphasia are very different from that of our patient, in whom the aphasia began insidiously and progressed gradually over a period of years.

Aphasia can result from mass lesions, especially neoplasms. Apart from tumors, other mass lesions of the cerebrum include bacterial abscesses, protozoal diseases (such as toxoplasmosis), and, in some settings, helminthic infestations such as cysticercosis and paragonimiasis. However, an expanding intracranial mass is likely to result in headache, nausea, vomiting, and various neurological signs such as hemiparesis, visual field abnormalities, sensory abnormalities, and seizures. Our patient did not have constitutional complaints, such as headache, vomiting, or fever, and there was no clinical evidence of a seizure disorder apart from generalized myoclonic jerks that were witnessed by his wife. Late in the course of the illness two clinicians witnessed brief, focal myoclonic jerks of the right arm that occurred spontaneously or with intention, but not in response to startle.

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a neurodegenerative syndrome characterized by language deterioration that worsens gradually in the absence of other cognitive deficits during the first 2 years of the illness. Patients with PPA usually present with complaints of difficulty finding words and decreased fluency, but they may come to medical attention because of poor comprehension or dysprosody. Dyscalculia, ideomotor apraxia, constructional deficits, and perseveration are consistent with the syndrome as long as they are not severe enough to affect the patient's daily life.

1 In most reported cases of PPA, the language disorder eventually progressed to dementia with involvement of multiple cognitive domains.

2–4The most common PPA syndrome is a nonfluent language disorder with neuropathologic findings within the spectrum of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) pathologies. Anomia, mild agrammatism, and impaired fluency are the most common features of this PPA syndrome.

5,6 The spectrum of FTD includes an autosomal dominant dementia in which nonfluent aphasia is an early and progressive affliction.

7 Of these hereditary cases, two who had experienced aphasia came to autopsy. One had spongiosis affecting the entire cortical depth, and the other had spongiosis only in cortical layer II. Patients with nonfluent PPA have commonly had these nonspecific changes consisting of neuron loss with gliosis and spongiform degeneration in the superficial cortical layers. This is the picture of “dementia lacking distinctive histology,” a pattern seen in many cases of FTD

4,8,9 and one that is associated with reduced tau expression.

10Nonfluent language impairment has also been associated with the underlying pathologic changes of Pick's disease, a form of FTD.

11,12 One patient with Pick's disease has been reported whose main clinical feature was a severely anomic PPA with relatively preserved reading and writing, especially typing. Microscopic examination of the brain revealed Pick bodies and neurofibrillary tangles in the absence of neuritic plaques.

11 Another patient with a halting, nonfluent aphasia was found to have swollen, achromatic neurons, similar to Pick cells, with greatest density in all cortical layers of the left superior frontal gyrus.

13 These findings have been likened to those seen in corticobasal degeneration.

14Semantic dementia, a form of FTD, is a cause of progressive fluent aphasia. In this disorder deficits of comprehension accompany a more generalized semantic deficit in which patients lose not only access to the meanings that are associated with words but also access to the meanings associated with other percepts, for example, object agnosia or prosopagnosia from right temporal involvement.

15 In a series of 16 patients with progressive aphasia, six patients were observed to have a dysnomia with fluent output but normal articulation, prosody, and syntax.

9 Comprehension was better for spatial prepositions and complex syntax than for nominal terms, and semantic paraphasic errors outnumbered phonemic paraphasias. Three of these patients subsequently developed visual object agnosia, and a fourth had mild prosopagnosia. One patient was noted at autopsy to have gross atrophy of both frontal and temporal lobes with spongiosis and other changes consistent with FTD.

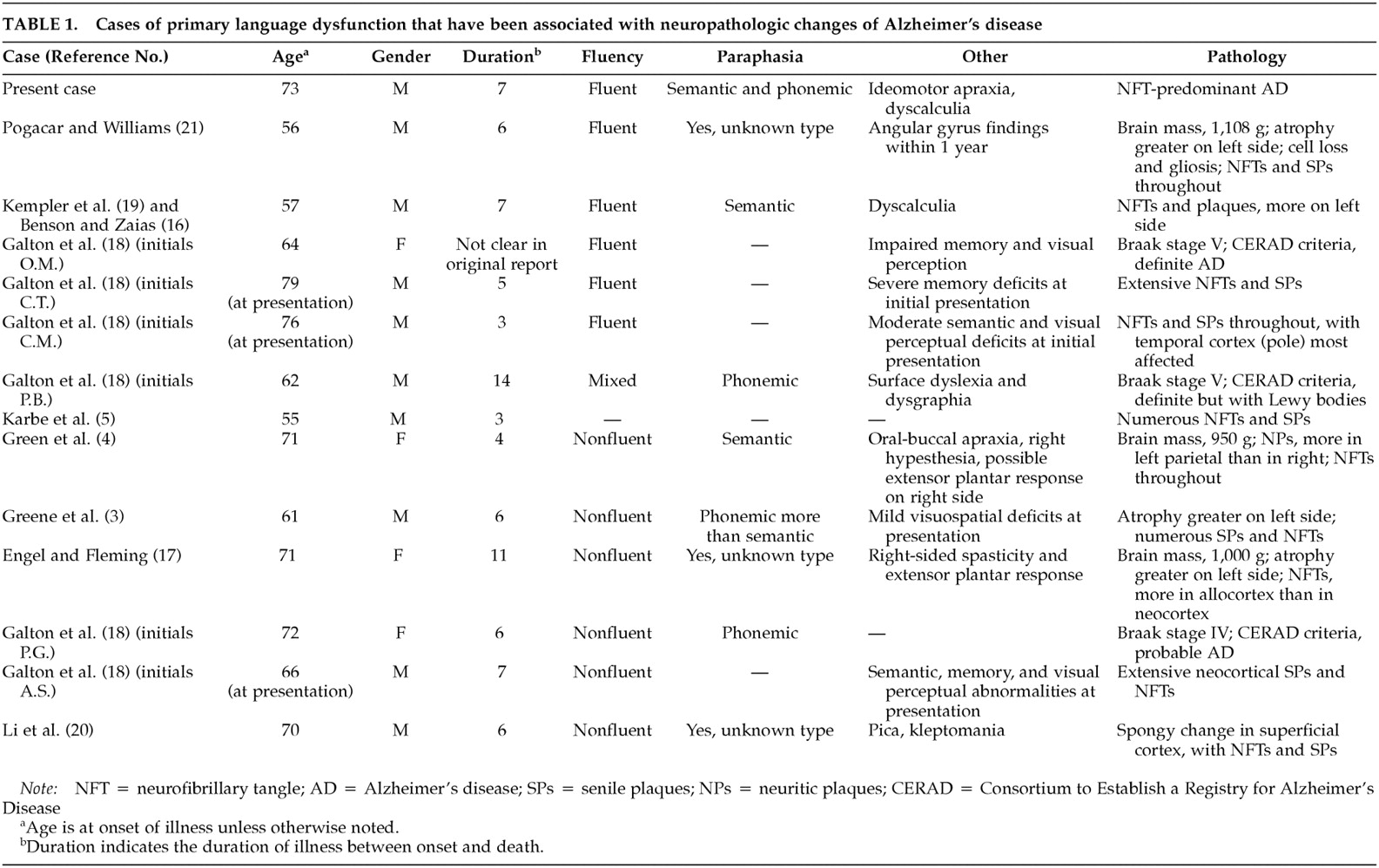

In addition to FTD spectrum conditions, Alzheimer's disease (AD) has been reported as the underlying cause of slowly progressive aphasia (see

Table 1).

3–5,16–21 Approximately half of the published cases of PPA with underlying pathologic changes of AD have been nonfluent.

22 Some patients have had classic pathologic findings of AD in a somewhat atypical distribution involving the left perisylvian language areas. Other investigators have reported patients with PPA and predominant neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the language-related cortex of the left cerebral hemisphere.

3,4 Two other nonfluent PPA cases have been reported in which Alzheimer-type changes were found in the temporal neocortex but with relative sparing of the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex.

18 Fluent PPA has been associated with changes of AD.

16,21 Autopsy may reveal extensive Alzheimer-type changes in the medial temporal lobe and the temporal neocortex in these patients. Finally, neuropathologic changes of AD may be associated with a “mixed” PPA that is not easily classified according to the fluent-nonfluent dichotomy.

18There is no clear consensus on the contribution of Alzheimer's disease to PPA syndromes. In a review of nearly 50 autopsied cases of PPA, fewer than 20% were found to have AD.

1 In an extensive 1996 review of the literature on PPA, 31 cases were reported, of which 24 were nonfluent (77.4%) and seven were fluent (22.6%).

23 AD was the underlying pathologic abnormality in five cases (16.1%), two with nonfluent aphasia and three with fluent aphasia. The two nonfluent AD cases constituted 8.3% of all nonfluent cases reported, and the three fluent AD cases constituted 42.9% of all fluent cases. These data suggest that AD may be somewhat more likely to result in fluent than nonfluent PPA and that AD is a much greater contributor to fluent PPA than to the nonfluent type.

However, some experts express doubt that AD causes PPA or that AD is truly responsible for such a large proportion of cases.

1,14 Mesulam emphasizes that the changes of AD may distract attention from more subtle findings; these characteristic AD changes are very likely to be present if the autopsy is performed more than a decade after disease onset.

1 Furthermore, the pattern of apolipoprotein E genotypes seen in AD is different from that seen in PPA, with PPA patients fitting the profile of a control population.

24 Kertesz and Munoz

14 raise the concern that some of the reported cases of PPA due to AD do not meet clinical criteria for PPA because of early impairment in nonlinguistic domains. In addition, some reported cases demonstrate changes consistent with “dementia lacking distinctive histology,” on which the changes of AD are superimposed,

17,20 and one case was noted to have Lewy bodies in addition to the neuropathologic changes of AD.

18 Engel and Fleming

17 do not consider the diagnosis of AD in their case to be definitive because of the atypical distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and the presence of superficial spongiform changes in the neocortex.

Patients with progressive fluent aphasia and histopathologic changes of AD have other evidence of early temporoparietal dysfunction. Among the fluent AD cases that have been reported, dyscalculia was a prominent feature in three patients.

16,21 These patients may also have other deficits consistent with an angular gyrus syndrome (e.g., left-right confusion), ideomotor apraxia, alexia, and agraphia.

18 Moreover, our patient exhibited a combination of phonemic substitution anomia and semantic anomia. Phonemic substitution anomia is a subtype of word-production anomia, in which the output is contaminated with inappropriate phonemes, a finding localized to the inferior parietal lobe.

25Apart from the progressive aphasia, this patient suffered from prominent dyscalculia, ideomotor apraxia, and an anomia that was best characterized as phonemic-substitution and semantic. These additional cognitive changes suggest the early parietal findings characteristic of AD but not FTD and make AD the most likely diagnosis. Seeking these key neurobehavioral features may have utility in the clinical identification of future cases in which primary progressive aphasia results from AD instead of FTD.

Clinical Diagnosis

Alzheimer's disease presenting with progressive aphasia.

Pathologic Discussion

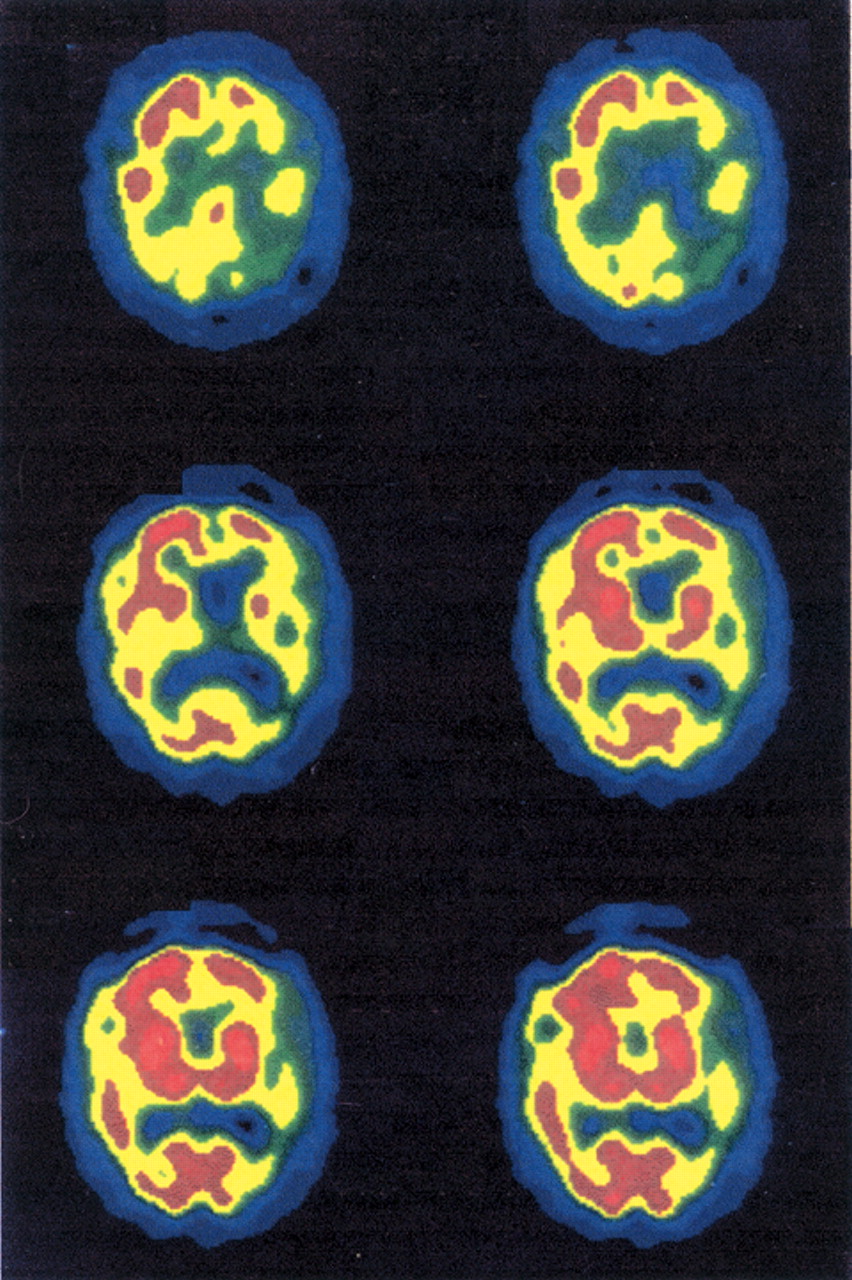

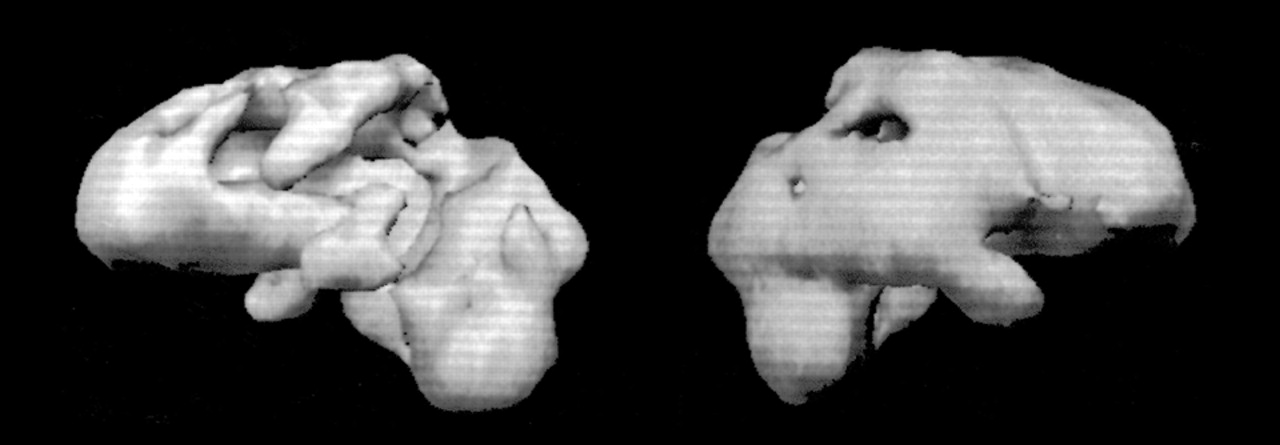

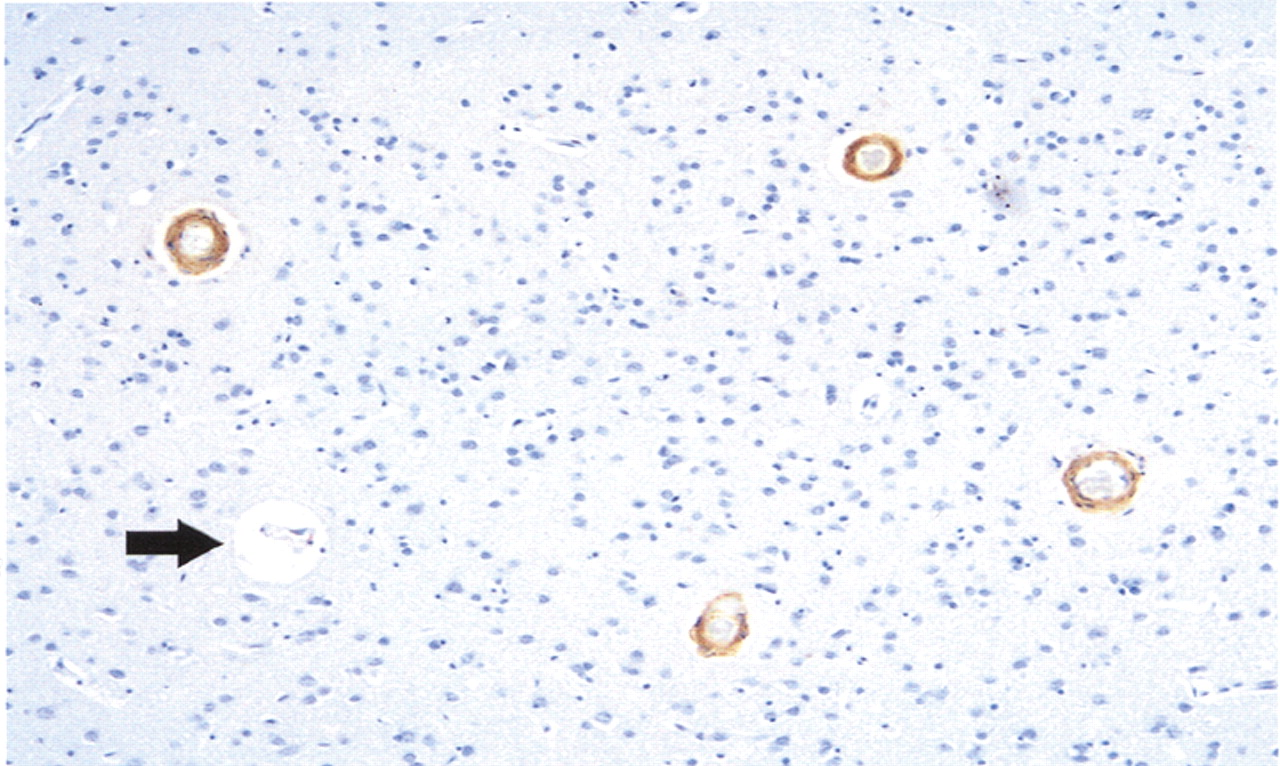

Autopsy examination revealed a thin subdural hematoma that was noted over the cerebral convexities bilaterally. Brain weight prior to fixation was 1,170 grams. There was only minimal cortical atrophy externally and on coronal sections of the fixed brain. Histologic sections were submitted in accordance with the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center dementia study protocol; this included sections from all lobes of the cerebral cortex together with subcortical white matter, hippocampi, deep central gray structures, brainstem, and cerebellum. The sections were stained with routine and Bielschowsky (silver) stains, and immunohistochemistry incorporating primary antibodies to amyloid beta (Aβ) (amino acid lengths of 1–40 and 1–42), tau, and ubiquitin. Neuritic and diffuse senile plaques (Aβ 1–42 immunoreactive) were especially prominent in occipital lobes. Tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles were abundant in the neocortex and hippocampi, and amyloid angiopathy was widespread, as highlighted by Aβ 1–40 immunostaining (see

Figures 3 and

4). Although severity of cerebral amyloid angiopathy reached Vonsattel grade 2–3 in the most severely involved regions (that is, there was complete replacement of arteriolar walls by amyloid, with perivascular extension of amyloid protein), parenchymal infarcts and hemorrhages were not appreciated.

26No Pick bodies were identified. Lewy bodies were absent from the substantia nigra and the neocortex, both on routine and ubiquitin-immunostained sections. Comparison of identical regions of neocortex from dominant and nondominant cerebral hemispheres—including senile plaque and neurofibrillary tangle counts within angular gyri—revealed no difference in plaque type, distribution, or density. Spongiosis involving superficial cortical layers was not observed. Abundant rodlike Hirano bodies were seen in both hippocampi.

Pathologic Diagnosis

Neurofibrillary tangle–predominant Alzheimer's disease.