Neurocognitive dysfunction has been established as a core feature of schizophrenia.

1–2 Many studies have shown the presence of generalized cognitive dysfunction,

3 and among other deficits, executive dysfunction,

4–7 attentional impairment,

8–9 memory deficits

10–11 and psychomotor slowing

12 are the most consistently reported findings. Evidence has already shown that healthy comparison subjects outperform patients on many cognitive tasks.

3 However, an open question is the selectivity of the deficits, as compared to the global cognitive level, which has consistently been shown to be deficient in patients with schizophrenia.

13–14Although many studies have reported executive dysfunction,

4–7 others have shown that the performance of patients with schizophrenia is not uniformly impaired on tests that measure the cognitive abilities termed executive functions.

17–19 One reason for the controversial findings is the lack of a strict definition of these functions and the fact that none of the available neuropsychological tests is a pure measure of executive functioning. The concept, as defined in the current literature, is comprised of a combination of abilities like abstraction and planning, set shifting, mental flexibility, and response inhibition in pursuit of a long-term goal. One approach to this methodological problem could be to dissect the concept to simpler components.

Furthermore, since we are still far from delineating the exact neurobiological substrates for many cognitive functions, the question of whether a putative deficit can be explained by other impairments in information processing still needs to be addressed by proper inferential statistical methods. Some studies,

19 for instance, included set shifting and response inhibition abilities among executive functions, whereas others

3 were designed with the assumption that these abilities reflect attention and vigilance. Given that vigilance needs to be maintained throughout the performance of the tasks that tap these functions, it is inconceivable that these tasks would be unrelated to attentional abilities. General level of intelligence is another possible confounder. Although many other confounders such as age, gender, medication use, chronic hospitalization and symptom severity have been controlled by proper study design or statistical methods, the impact of general intelligence and attention has been neglected in many studies that reported significant executive dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia.

Given the complexity of the concept of executive functions, we were interested in delineating the performance of patients with schizophrenia on tasks that tap abilities like set shifting, response inhibition, category formation, and tendency to perseverate, rather than measuring “executive function” as one single cognitive ability. We hypothesized that these abilities would show different degrees of impairment if controlled for attention and general intelligence.

RESULTS

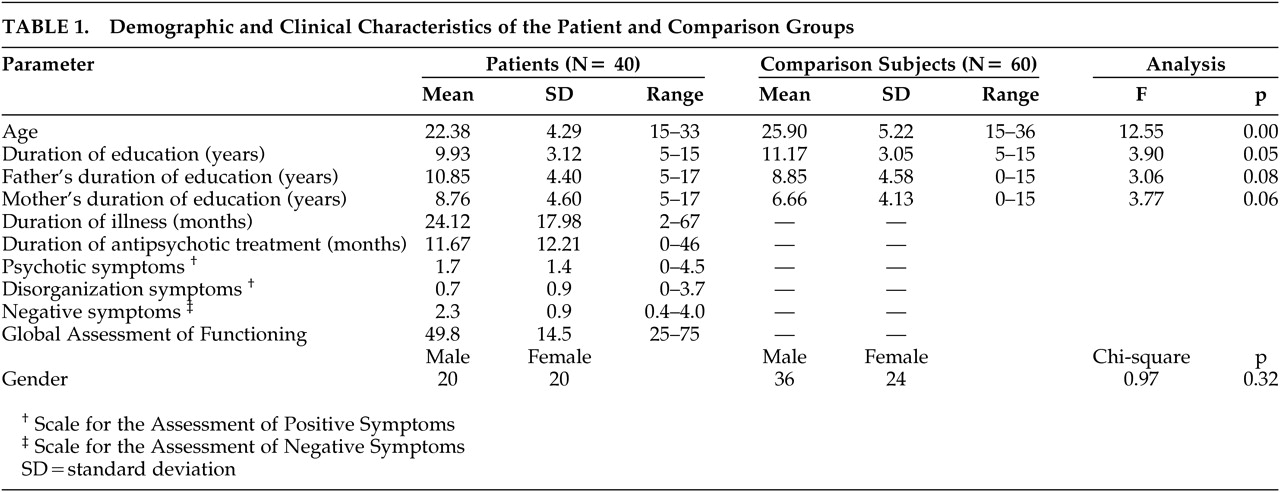

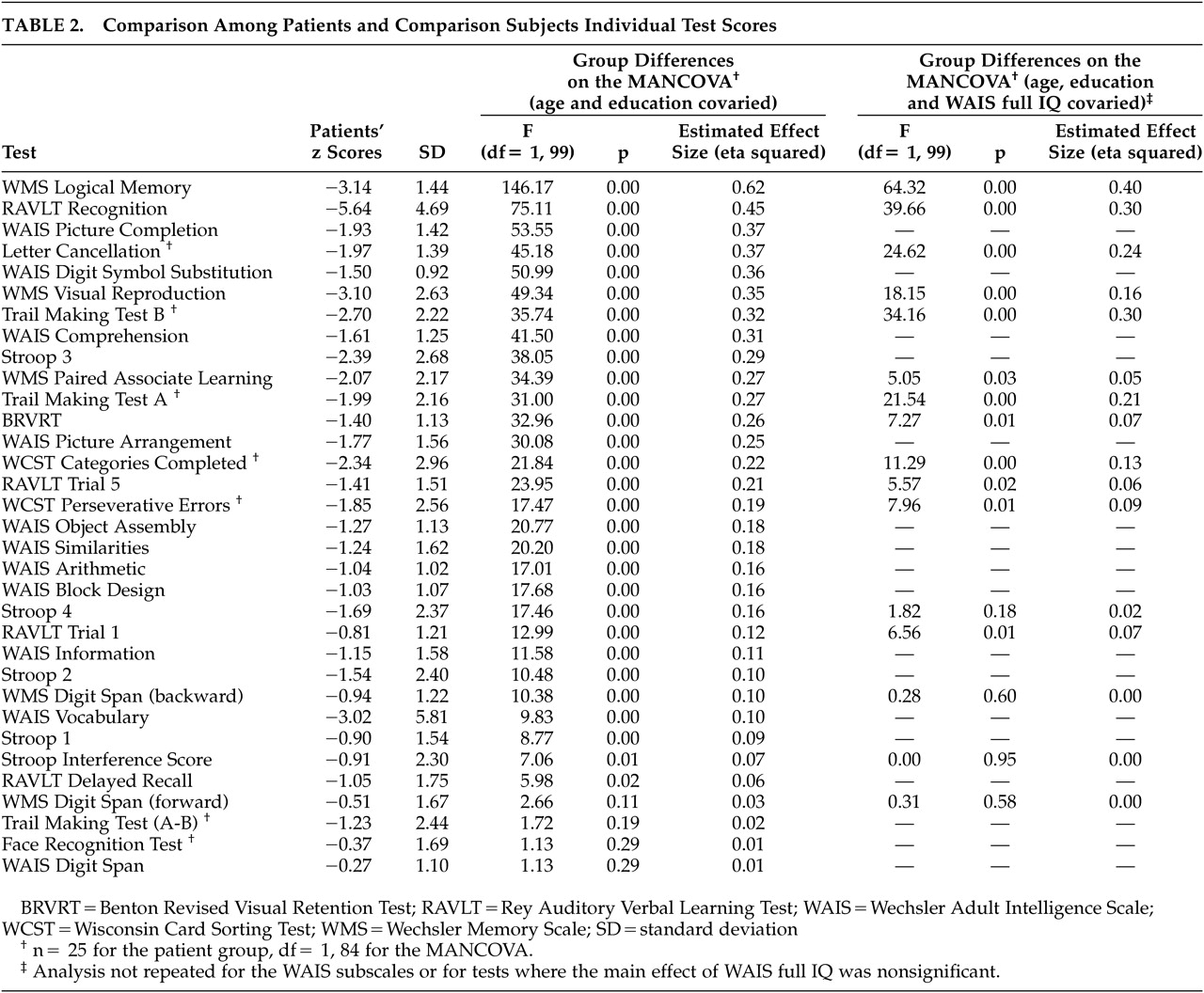

The initial MANCOVA where age and education were covaried demonstrated that the patients’ performance was significantly worse than and 1–5 SD’s below the performance of healthy comparison subjects on all tests, with the exception of Digit Span on the WMS and the WAIS, Face Recognition Test, and the A–B Difference on the Trail Making Test (

Table 2).

We examined the effect of attention by repeating the analysis of variance with the freedom from distractibility score as an additional covariate. Although the main effect was significant for letter cancellation and WMS Visual Reproduction, group differences remained significant with large effect size estimates for both tests (F=29.70, p=0.00, eta squared=0.27 for letter cancellation, and F=36.84, p=0.00, eta squared=0.28 for WMS Visual Reproduction).

On the other hand, the main effect of the general intelligence level was significant for many tests. Group differences and the magnitude of the difference for each test are shown in

Table 2. Verbal declarative memory (WMS Logical Memory and RAVLT Recognition) and general psychomotor speed (Letter Cancellation Test and Trail Making Test) were the only domains where group differences remained significant after controlling for the general level of intelligence. It is particularly noteworthy that either no significant group differences were found or the magnitude of group differences was small for the abilities of set shifting, response inhibition, concept formation and mental flexibility, as measured by the Trail Making Test A–B difference, Stroop Interference score and the Categories Achieved and Perseverative Errors on the WCST, respectively.

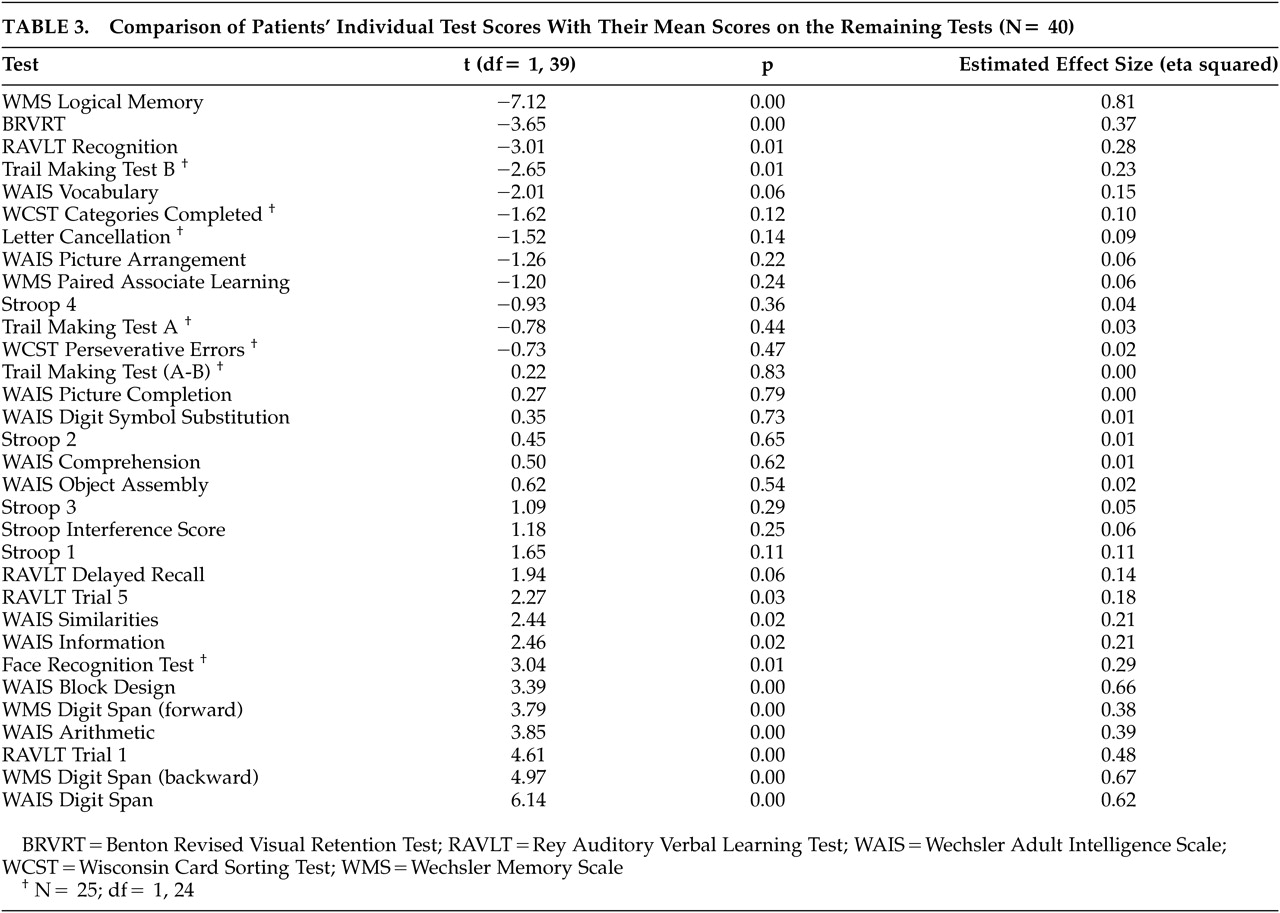

Comparing the patients’ performance on each test with the mean of the remaining tests revealed significantly greater impairment in the WMS Logical Memory, BRVRT, RAVLT Recognition, and Trail Making Test B scores. The estimated effect sizes were large (>0.29) for the former two (

Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study opted for a conservative approach in analyzing group differences and took into account the effects of attention and general level of intelligence in addition to age and education. The magnitude as well as the significance of the group differences was observed.

The most important finding is a sparing of set shifting and response inhibition abilities in patients in the first 5 years of the illness, as measured by the Trail Making Test A–B difference and the Stroop Interference Score, respectively. Abilities like concept formation and mental flexibility, as measured by the number of categories achieved and perseverative errors on the WCST, respectively, were also relatively less impaired.

Although the Trail Making test B has been used in some studies as a measure of set shifting abilities, the A–B difference, which controls for the effect of general psychomotor speed, might be a more accurate measurement.

35–36 Our results point to a significant group difference in the general psychomotor speed (Trail Making A) and attention (Trail Making B) in contrast to the nonsignificant difference in the set shifting ability (Trail Making A–B difference).

The small magnitude of between-group differences on the WCST along with preserved set shifting and response inhibition abilities point to a relative sparing of the cognitive abilities that have been called “executive functions.” These results are consistent with the findings of Hutton et al.

37 who reported relatively unimpaired set shifting abilities in first-episode patients. Similarly, Goldstein et al.

38 found that dense perseverative behavior is not common to all patients with schizophrenia. Comparing the discriminative power of the WCST and the WAIS, Dieci et al.

17 demonstrated a lack of selectivity of the WCST performance in identifying individuals with schizophrenia from healthy comparison subjects.

On the other hand, studies that showed impaired WCST performance outnumber the ones that demonstrated a sparing of these functions. Our results therefore require explanation.

First, “executive functioning” remains a somewhat elusive construct. The classification of the four abilities we studied (set shifting, response inhibition, concept formation and mental flexibility) as “executive functions” is not based on a definite neurobiological substrate they all share. The cerebral localization of the cognitive abilities termed executive functions also remains elusive and controversial. Regions of the prefrontal cortex may play a special role in recruiting other brain areas in a series of distributed networks that handle different components of executive functions, depending on the processing demands of the specific task.

39 Results from other studies also suggest that the cognitive abilities collectively termed as “executive functions” differ from one another in many aspects and may be better studied when measured separately. One example is the difference in their span of development: Pantelis et al.

19 have recently suggested that cognitive functions developing earlier in life (e.g., set shifting abilities) are less likely to show deficits, whereas those that take longer to fully develop (e.g., declarative memory or executive function on the WCST) are more likely to be impaired. Preserved set shifting and response inhibition abilities in our group suggest that more strict definitions of executive functions might be useful in future studies.

Second, the degree of the impairment in set shifting abilities might be related to the chronicity of the illness. Hutton et al.,

37 for instance, showed relative unimpairment of these abilities in first-episode patients, while Elliott et al.

40 found that patients with moderately severe schizophrenia, like frontal lesion patients, showed a specific deficit in set shifting ability due to a tendency to perseverate. Our patient group with a mean illness duration of 2 years might be more similar to first-episode patients in terms of their set shifting abilities.

Third, any study on the relative impairments in cognitive functions might be biased because of a difference in the level of difficulty on tests that are assumed to measure different functions.

41–42 It must be noted that this study is not exempt from such a possible problem. It is our belief, however, that controlling for attention and the general level of intelligence has partly compensated for a possible bias.

Group differences on verbal declarative memory and general psychomotor speed remained significant with large ES estimates, even after controlling for the general level of intelligence. In fact, the differences on the two tasks that reflect verbal declarative memory (recall on the WMS Logical Memory and recognition on the RAVLT) have the largest magnitudes of difference (

Table 2). Performances on these two tasks were most impaired within the patient group compared to the mean of the remaining tests (

Table 3). In their recent comprehensive review, Cirillo and Seidman

43 have concluded that, along with attention and executive functions, verbal declarative memory is among the most impaired neurocognitive domains in schizophrenia. Our results are in line with these findings. However, as pointed out by Chapman and Chapman

41 and Russell,

42 the possibility that the tests used to measure verbal declarative memory might be more sensitive to any brain impairment cannot be ruled out. Therefore, the specificity of the tests for schizophrenia need to be studied before drawing conclusions about the presence of a differential deficit in verbal declarative memory in schizophrenia.

Significant psychomotor slowing in the patient group might be a consequence of the antipsychotic medications as well as a feature of the illness. Similarly, anticholinergic medications or the anticholinergic properties of the antipsychotics would be expected to have a differential effect on the tests that measure memory. However, since the number of patients on an anticholinergic medication was small and the mean daily dose was not high, it is unlikely that the anticholinergics had a major effect on the overall measures of memory.

Possible differences between the socioeconomic classes of the two groups cannot be ruled out. However, similar levels of parental education in the two groups suggest that the groups were similar in terms of their socioeconomic classes. The similarity between the two groups on the WAIS Vocabulary and Information subtests is also assumed to reflect a similar premorbid level of intelligence between the groups.

44Overall, these results point to preserved set shifting and response inhibition abilities and a relative sparing of concept formation and mental flexibility in schizophrenia patients in the first 5 years of the illness. Study of individual executive functions separately by tests that are matched for the level of difficulty might support this finding and show that schizophrenia patients might be heterogeneous in terms of their cognitive abilities termed as executive functions.