Personality change due to traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the latest term given to a syndrome which has been recognized in one form or another for hundreds of years.

1 The current nomenclature established in DSM–IV

2 and was maintained in DSM–IV–TR.

3 The DSM

3 has postulated the existence of five major subtypes of personality change due to TBI that have remained relatively stable for almost 20 years: affective lability, aggression, disinhibited, apathetic, and paranoid. Other terms for the condition or its subtypes have included organic personality syndrome,

4 frontal lobe syndrome,

5 comportmental learning disabilities,

6 acquired sociopathy,

7 posttraumatic chronic behavior disorder,

8 and the regional prefrontal syndromes (e.g., dysexecutive, disinhibited, apathetic types).

1Despite the wide recognition of the classical clinical presentation of personality change due to TBI, there has been very little systematic research devoted to clinical predictors and correlates of this syndrome. Until recently, the authors have lacked a research instrument to diagnose the syndrome.

9 Even when single case or small case-series reports have provided information on this condition, the diagnosis has been seldom termed personality change due to TBI.

6,10–12 Prior to our investigations of personality change, there were only two reports of personality change due to traumatic brain injury-type behavior from unselected cohorts of children with TBI.

13,14 These reports together showed that between 16% and 38% of children with severe TBI developed the syndrome.

The authors reported that a persistent form of personality change occurred in 14/37 (38%) of children consecutively hospitalized with severe TBI an average of 2 years after injury.

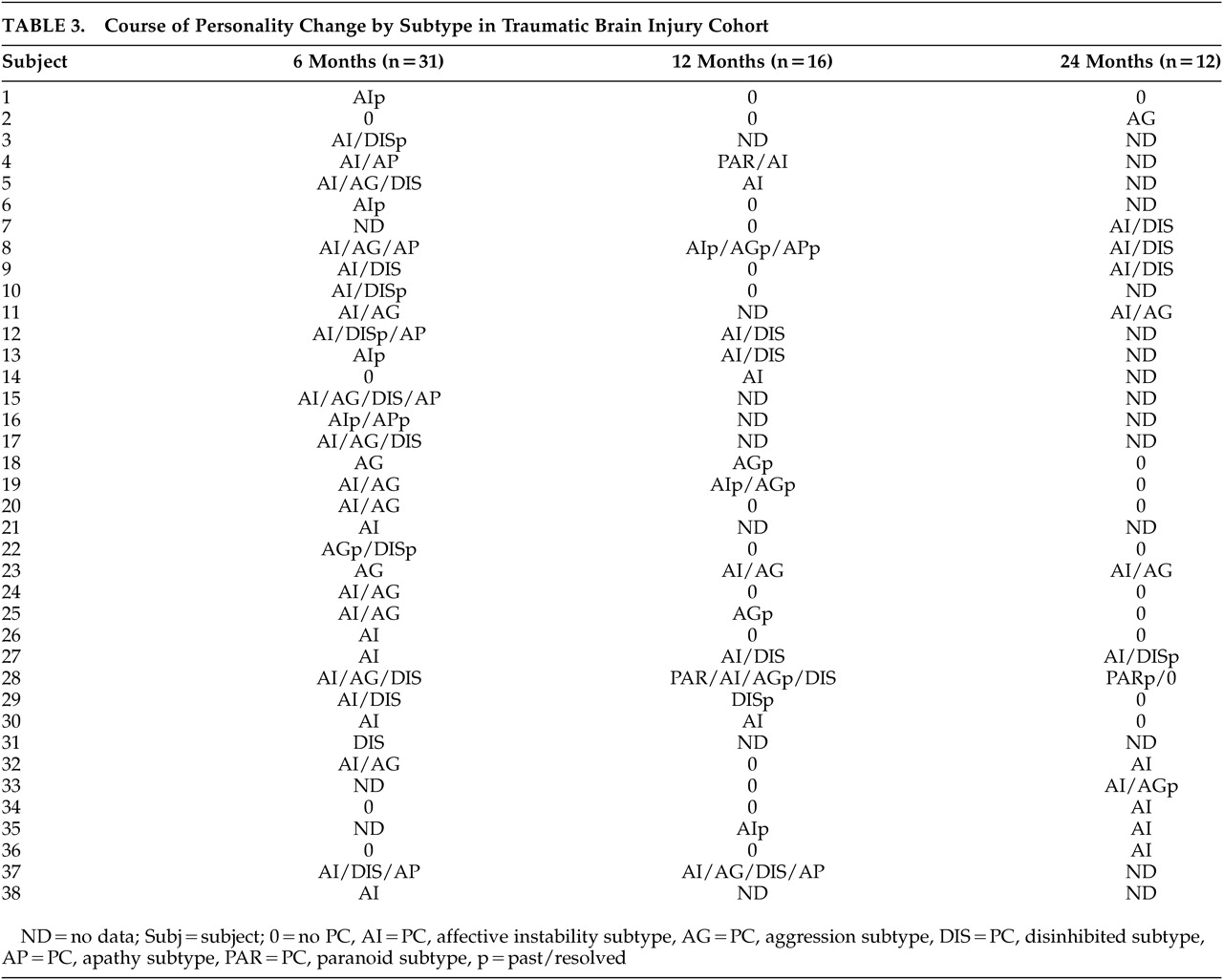

15 An additional 8/37 (22%) of these children had a transient form of personality change due to TBI suggesting the need to investigate injury and psychosocial factors in personality change outcome. Persistent personality change in those children with severe TBI was significantly associated with severity of injury, adaptive and intellectual functioning deficits, and comorbid diagnosis of secondary attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, although it was not related to psychosocial adversity. Our data provided information about the form of personality change. The affective instability subtype was the most common form of personality change with the aggressive and disinhibited subtypes being the next most common forms. The apathetic and paranoid subtypes occurred infrequently.

16 These findings were based on merged data from a retrospective and prospective study that did not investigate preinjury psychosocial variables.

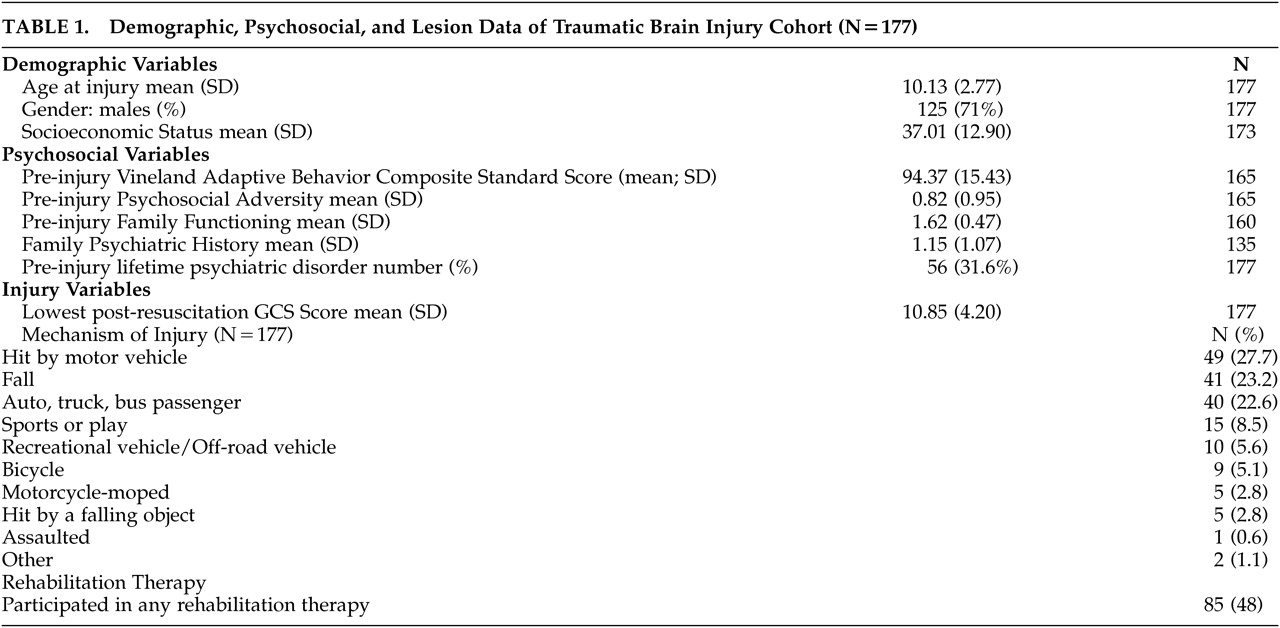

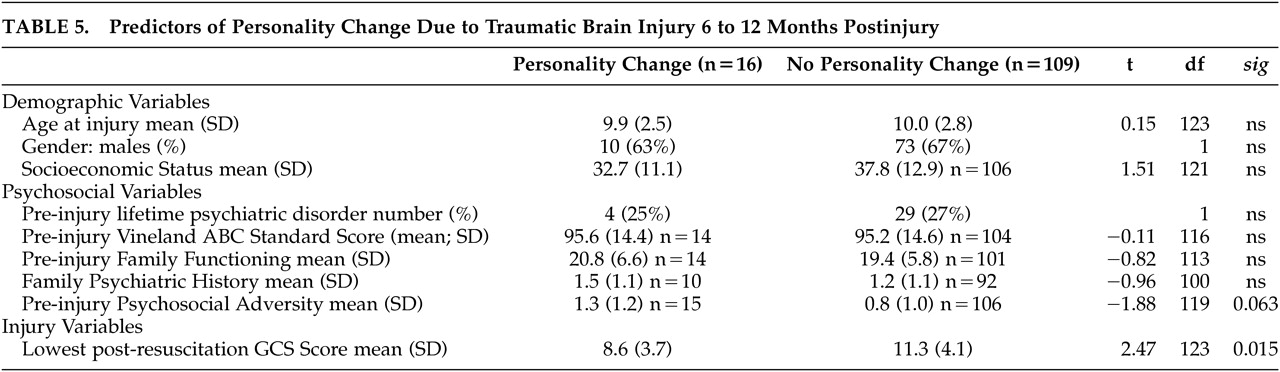

To expand knowledge of personality change beyond the studies described above, the authors conducted a large prospective study from which the authors report both shorter and longer term outcomes. During the first 6 months after injury, personality change occurred in 31/141 (22%) of children and was related to greater severity of injury although not to any demographic (age, gender, race, socioeconomic status) or preinjury psychosocial variables (family psychiatric history, family function, lifetime psychiatric disorder, adaptive function, psychosocial adversity).

17 Furthermore, lesion analysis based on research protocol MRI scans confirmed our hypothesis of a significant association between lesions of the superior frontal gyrus and personality change even when the presence of “any lesion” and also when severity of injury was controlled for in separate analyses. This was consistent with neuroscience evidence that the dorsal prefrontal region is implicated in states of affective dysregulation.

18The present study is concerned with longer-term outcome, from after the first 6 months after injury to 2 years postinjury. The authors hypothesized that 1) personality change would be significantly related to severity of injury and that lesions of the superior frontal gyrus would remain a significant predictor of personality change present between 6 and 12 months and between 12 and 24 months after injury; and 2) In view of the fact that a subgroup of children with personality change experience remission of their syndrome with the progression of time,

15 personality change at the assessments further from the time of injury would be significantly related to measures of preinjury psychosocial function (e.g., socioeconomic status [SES], family psychiatric history, family function, psychosocial adversity, or adaptive function).

DISCUSSION

Personality change is a relatively common complication of head trauma in children. The new pieces of information in this article are that the occurrence of personality change evolves over time after childhood TBI; that injury severity and the presence of dorsal frontal damage increase the occurrence of personality change, and that preinjury adaptive function is a predictor of long-term personality change.

The occurrence of personality change declined from the first 6 months after injury from 22% to a relatively stable rate of 12–13% from 6–12 to 12–24 months post injury. As in our previous study

15,16 and the 6 month follow up from this same cohort,

17 affective instability remained the most common subtype of the disorder, followed by the aggressive subtype and the disinhibited subtype. The apathetic and paranoid subtypes were rare and tended to resolve for unclear reasons. Personality change is significantly comorbid with several categories of new-onset psychiatric disorders including externalizing disorders (i.e., disruptive behavior disorders) and internalizing disorders (i.e., mood or anxiety disorders). This pattern of multiple comorbid diagnoses typically reflects increasingly severe psychopathology in psychiatric studies of children.

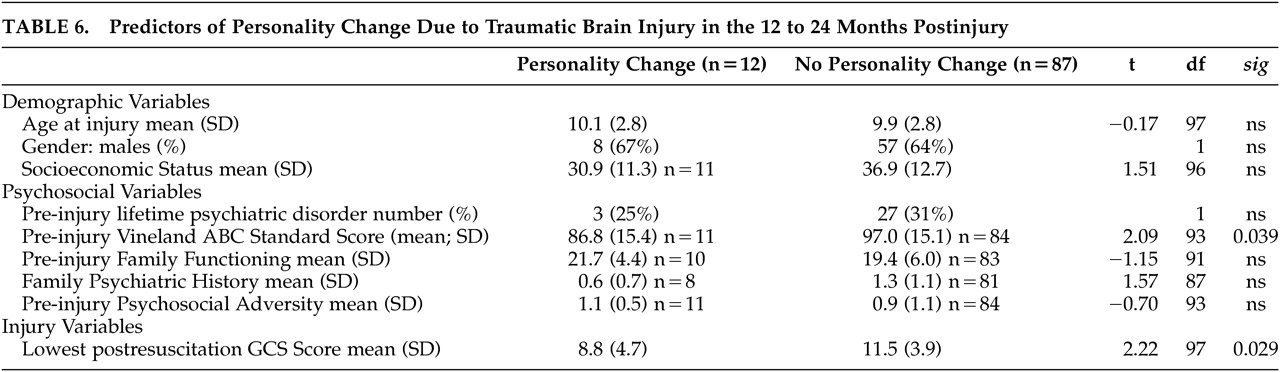

28Severity of injury was a consistent predictor of personality change during both follow up intervals. This effect is consistent with previous findings

15 and supports the validity of the diagnosis which is one of the few DSM–IV diagnoses which by definition is linked to a specific cause.

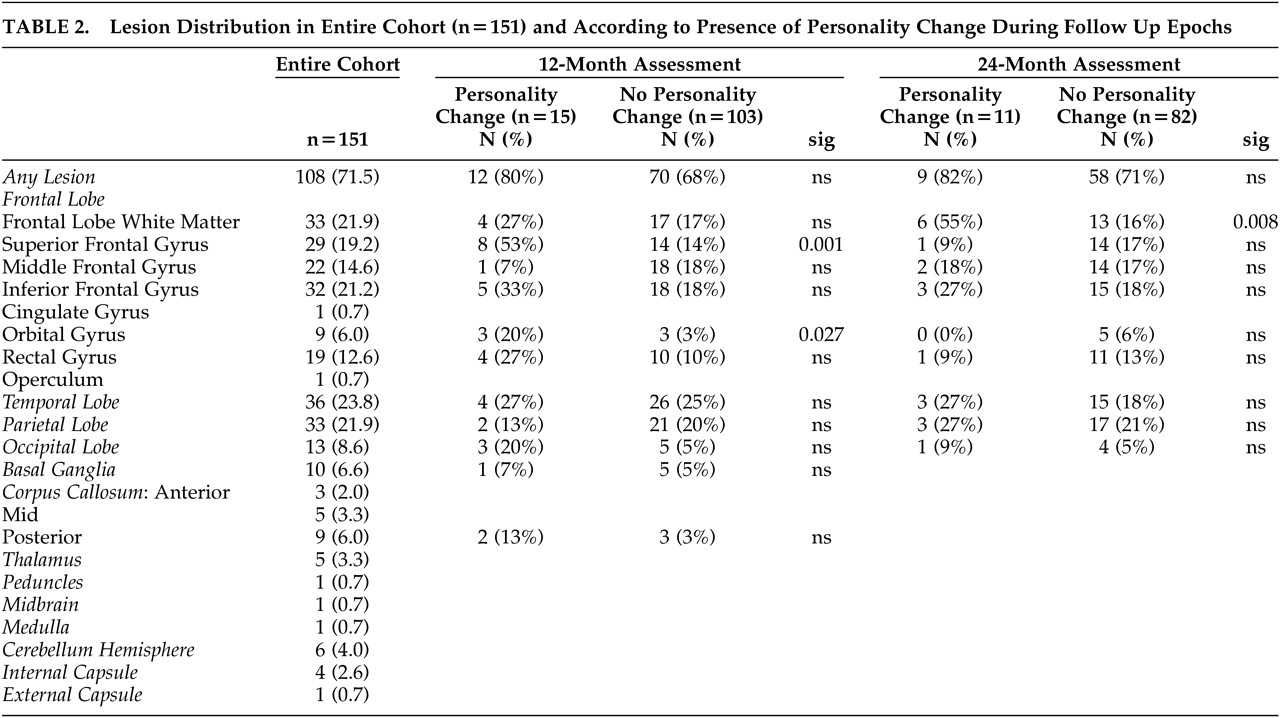

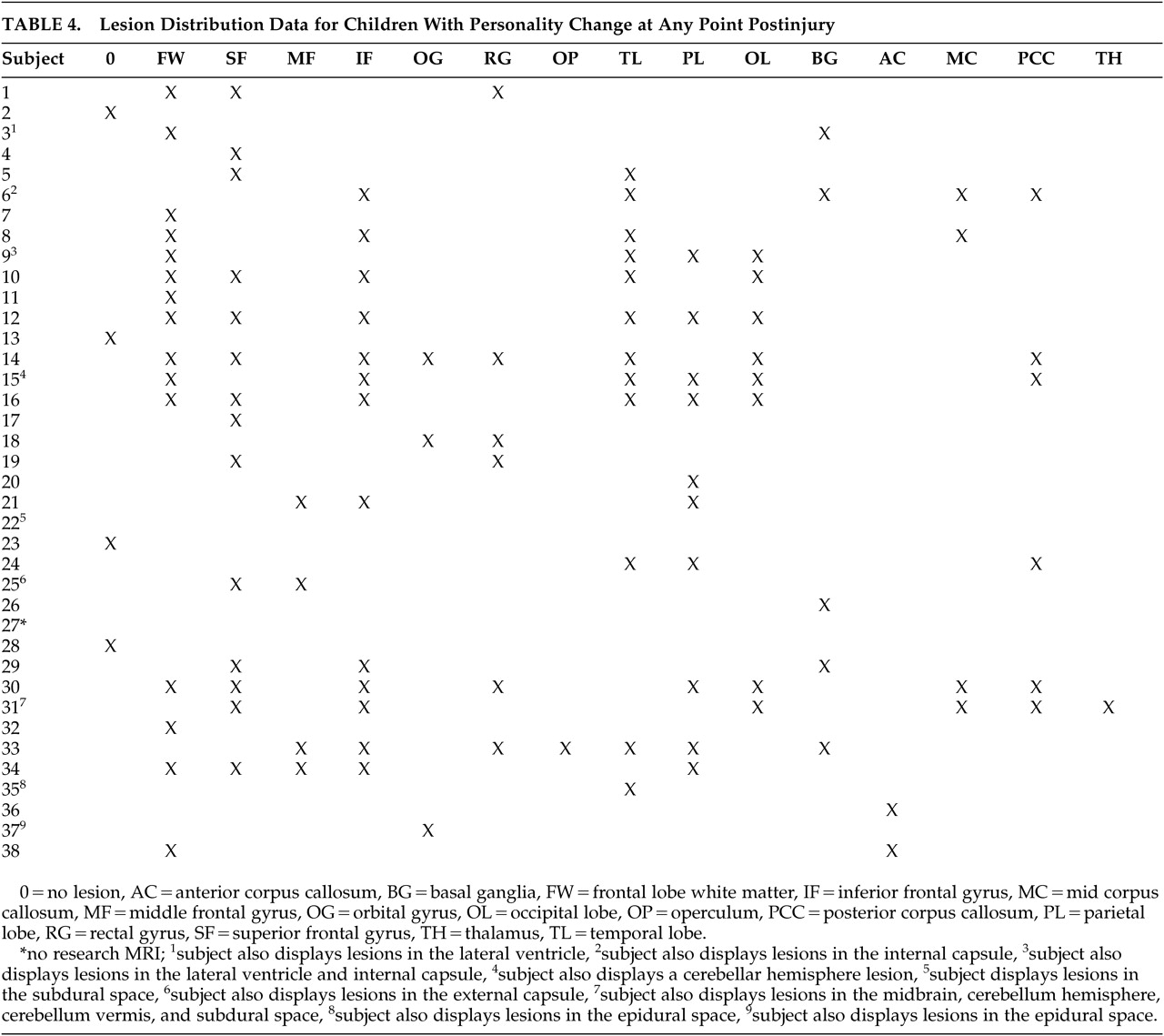

Not only was injury severity a predictor of personality change, but a more specific characterization of the pattern of the injury added to the predictive utility of injury indices. Indeed, the authors found, as hypothesized, that lesions within the superior frontal gyrus predicted personality change between 6 and 12 months post injury. Furthermore, this specific lesion predictor contributed independently with regard to severity of injury to the prediction of personality change which result is similar to our earlier finding for personality change presenting between injury and 6 months post injury.

17The finding that frontal lesions are involved in the generation of personality change is consistent with models of affective regulation developed to explain the pathophysiology of depression.

29,30 In these models, the dorsal frontal system, which includes dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus, and hippocampus, is important for effortful regulation of affective states resulting from the activity of the ventral system. The ventral neural system, which includes amygdala, insula, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, ventral anterior cingulate gyrus, thalamus, ventral striatum, and brainstem nuclei, is necessary for the identification of the emotional significance of environmental stimuli, and the production of affective states. The ventral system is also important for regulation and mediation of autonomic responses to emotional stimuli and contexts accompanying the production of affective states. In personality change associated with superior frontal gyrus injury, the complex interconnectivity between the dorsal and ventral systems is likely disrupted such that affective states produced by the ventral system cannot be sufficiently regulated by the dorsal neural network.

The finding that preinjury adaptive function predicted personality change at the 2-year assessment is new and suggests that even in this disorder, the behavioral manifestations of which are classically associated with the direct effect of brain damage, preinjury personal characteristics of the child may influence outcome. The design of our previous study (based on a combined sample of children prospectively and retrospectively recruited) precluded the investigation of preinjury psychosocial variables as potential predictors of personality change but as in the present study showed that severity of injury remained a significant predictor of personality change approximately 2 years after TBI. A possible explanation for this finding is that with the process of recovery, preinjury brain reserve

31 or previously learned socialization and broader adaptive behavior skills reemerge more readily, albeit belatedly, to result in improved modulation of affect, aggression, and disinhibited behavior. Another possible explanation is that measures of preinjury adaptation may be markers of the ability to relearn inhibitory control and modulate affect. Preinjury psychosocial variables commonly influence early and later behavioral outcome,

13,32,33 therefore the delayed emergence of significance for preinjury adaptive function (in this instance) may serve to emphasize the close relationship of personality change to injury variables early in the follow up.

Another change in the pattern of predictors of personality change with the extended follow up was the emerging relationship with frontal white matter lesions and the loss of the relationship with superior frontal gyrus lesions. Closer review of the data shows that a number of children with personality change and superior frontal gyrus lesions experienced resolution of their personality change in the second year of follow up. However, there were also a number of children with personality change and superior frontal gyrus lesions whose data were missing at extended follow up. It is not possible to know how this may have affected the findings. The authors have shown that there was no association between superior frontal gyrus lesions and lack of follow up in the second year. Where possible, related neural structures might have subsumed the function of affective regulation, a process that was limited by severity of injury and diffuse axonal injury particularly in the frontal lobe. Frontal white matter is important in many cortical networks, and diffuse injury results in a less efficient and relatively less connected complex of neural systems.

34 More broadly, the data underscore the relevance of white matter damage to many adverse outcomes in childhood disorders of brain and behavior.

Our data on childhood TBI are both similar to and different from findings of a comparable study of adult TBI

35 in which aggression in adults was associated with preinjury personal psychiatric and behavioral history in terms of a higher rate of alcohol abuse, drug abuse, mood disorder, and legal interventions for aggressive behavior. However, preinjury personal history was evident as a predictive factor at the earliest points in follow-up in adults, in contrast to the delayed emergence of this factor (preinjury adaptive function but not preinjury psychiatric disorder indices) in children. Unlike the data in children, aggression in adults was not associated with severity of injury. The difference may be partly explained by the fact that the aggression ratings in the adults were postinjury scores and did not capture change from before injury, whereas personality change was diagnosed in the children only if the syndrome was a change from before injury.

The findings of this study must be considered within its limitations. Interrater reliability assessments for the diagnosis of personality change were not directly tested based on videotaped interviews. However, the child psychiatrists or psychologists at each site closely supervised the assessments; and, further, fidelity in diagnosis was maintained across sites by frequent telephone conferences and transmission of written summaries of psychiatric assessments that were critiqued by the first author and other interviewers, resulting in a consensus diagnosis. The image analysis did not employ volumetric measurements that might have more clearly delineated lesion correlates of personality change. However, the images themselves were of research quality required for such volumetric assessments that allowed project neuroradiologists to document even very small lesions. As in many long-term follow-up studies, attrition was notable yet remained stable between 25% and 27% at the 12-month and 24-month follow up assessment. Overall there were few demographic (e.g., African American children), psychosocial, or injury variables upon which the children who did not return differed from those who returned. While our hypotheses did not call for an orthopedic injury comparison group, such a group could control for new onset emotional lability in children predisposed to and exposed to injuries.

The study had a number of notable strengths. This is the largest prospective child TBI psychiatric interview study of a consecutively admitted nonreferred population. The breadth and depth of assessments were extensive and included interview assessments of psychopathology, adaptive function, and family psychiatric history, in addition to rating scales encompassing injury and other psychosocial risk factors for new onset psychiatric disorder. Furthermore, lesion analysis was based on readings by expert neuroradiologists. Importantly, relationships were not simply described but were explored in regression models.