Social cognition includes processes such as “theory of mind” skills, affect recognition, social cue perception, and attributional style.

1 Whether social cognition is relatively independent from other aspects of cognition

1 or it expresses the operation of neurocognitive abilities within social and interpersonal situations,

2 it has been linked to social behavior.

1 Impairment in social functioning (e.g., the ability to work, maintain interpersonal relationships, and care for oneself) is a hallmark characteristic of schizophrenia.

3 Consequently, various facets of social cognition in patients with schizophrenia have received growing attention in recent years (for a review of affect perception studies in schizophrenia see Mandal et al.

4 and Edwards et al.

5 and for a review of “theory of mind” studies in schizophrenia see Brüne).

6Affect perception refers to the ability to accurately perceive, interpret and process emotional expressions in others.

7 Prosody is a nonlexical component of speech and is divided into stress prosody, which entails decisions about semantic meaning and affective prosody, which communicates information about the emotional state of others. Perception of affective prosody refers to the recognition of emotion from prosodic intonation.

5In contrast to the volume of research on facial affect recognition in schizophrenia, the literature on the perception of affective prosody remains quite sparse.

5 Nevertheless, several studies have reported deficits in the perception of affective prosody in schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia were impaired on affective prosody recognition relative to healthy individuals

8–13 and patients with affective psychoses,

11 but they were equally impaired as patients with other psychotic disorders

11 and right brain damage.

12 These findings are relevant to first episode schizophrenia,

11 as well as both unmedicated

8 and medicated

9,10,12,13 patients who have had schizophrenia for a number of years. In these studies, patients presented a specific deficit in the recognition of negative emotions.

11,14 In contrast, one study of affective prosody in schizophrenia failed to find a deficit.

15 Performance on affective prosody recognition test in patients with schizophrenia has been associated with deficits on attention and executive functioning,

16 and rapid visual processing.

17Our objective for this study was to explore the ability of patients with schizophrenia to perceive affective prosody. More specifically, we were interested in whether these patients could perceive some, but not other, emotions. Finally, we explored gender differences in affect perception.

RESULTS

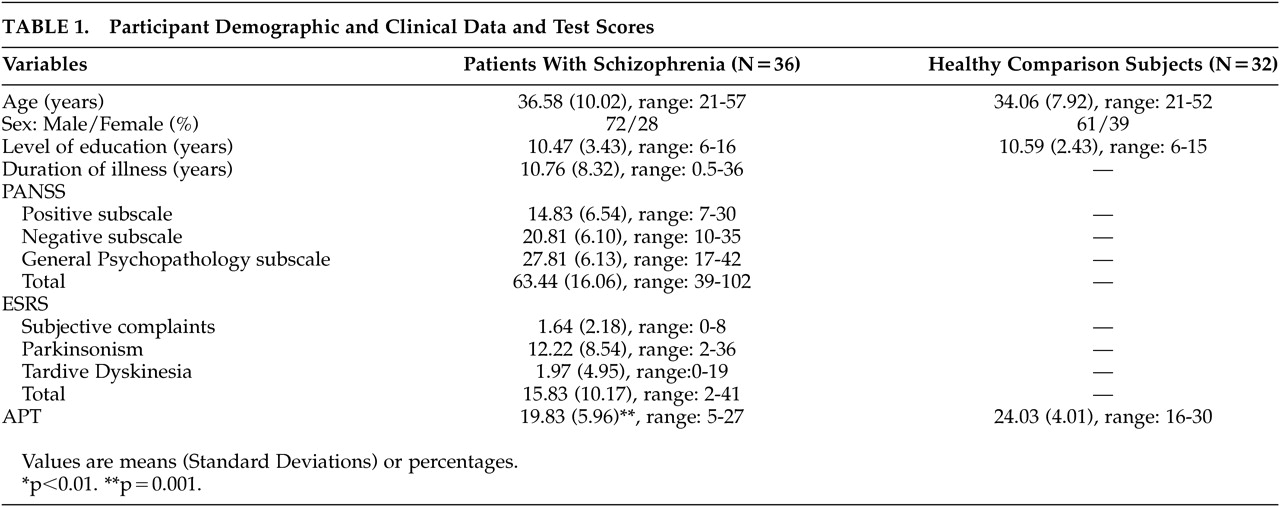

Patients with schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects did not differ significantly in demographic characteristics: age (F=1.30, df=1, 66, p=n.s.), male to female ratio (χ

2=0.88, df=1, p=n.s.), and level of education (F=0.28, df=1, 66, p=n.s.) (

Table 1).

The two groups differed significantly on the APT (F=11.32, df=1, 66, p=0.001), with patients with schizophrenia having lower scores than healthy participants (

Table 1). The mean accuracy of the patients on the APT was 66.1% (SD=19.87), and that of healthy comparison subjects was 80.19% (SD=13.37). When we conducted the same analysis for men and women separately, only men with schizophrenia had significantly lower scores on the APT than healthy men (F=3.04, df=1, 43, p=0.001), while women of the two groups did not differ significantly (F=2.10, df=1, 21, p=0.16). The mean accuracy of men with schizophrenia was 61.07% (SD=21) versus 78.83% (SD=13.07) for the healthy men, and the mean accuracy of women with schizophrenia was 74.03% (SD=15.43) versus 83.33% (SD=14.43) for the healthy women.

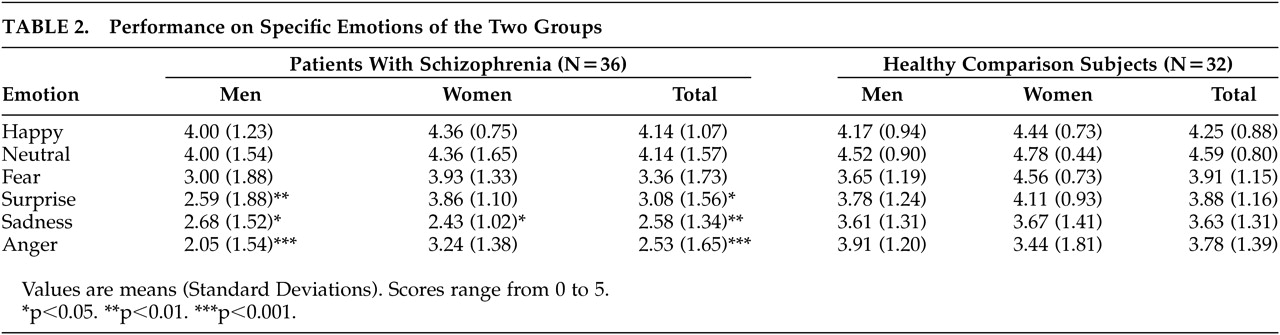

Regarding specific emotions, patients with schizophrenia as a group presented difficulties perceiving sadness (F=10.44, df=1, 66, p=0.002), anger (F=11.38, df=1, 66, p=0.001) and surprise (F=5.55, df=1, 66, p=0.021), but not happiness (F=0.22, df=1, 66, p=n.s.), fear (F=2.29, df=1, 66, p=n.s.) and neutral intonation (F=2.18, df=1, 66, p=n.s.) (

Table 2). Specifically, male patients with schizophrenia presented worse recognition of anger (F=19.00, df=1, 43, p<0.001), sadness (F=4.82, df=1, 43, p=0.034), and surprise (F=15.97, df=1, 43, p=0.008) than healthy men, while female patients with schizophrenia showed worse performance than the healthy women on processing sadness (F=5.99, df=1, 21, p=0.023).

The rank order of the six emotions from highest to lowest mean scores was similar for both groups. For the healthy participants, the rank order was neutral intonation, happiness, fear, surprise, anger, and sadness, and for the patients, the rank order was neutral intonation, happiness, fear, surprise, sadness, and anger.

DISCUSSION

Patients with schizophrenia presented significant impairment in the recognition of affective prosody. This finding is in accordance with previous reports in the literature examining affective prosody recognition in schizophrenia.

8–13Women with schizophrenia present a more favorable social course than men. This sex difference in the social course of schizophrenia may reflect the protective effect of estrogen in women, accounting for the older age of onset of schizophrenia in women. Consequently, women manage to attain a higher level of social, and, possibly, cognitive and personality development before illness onset. Thus, their social functioning may be less impaired by the illness than men (for a review of gender differences in schizophrenia see Häfner).

24 In accordance, women with schizophrenia have shown better absolute levels of verbal learning than males, although both groups were impaired relative to the general population.

25 It is accepted that verbal memory deficits in schizophrenia have been associated with all types of functional outcome.

26 In our study, only men with schizophrenia presented significant deficits on recognition of affective prosody compared with healthy men, whereas women of the two groups performed similarly on the APT. Affective prosody deficits in patients with schizophrenia have been found to be related to dysfunction in occupational performance.

13 In another study, inaccurate “affect recognition,” which was a composite index based on measures of vocal and facial affect identification, was associated significantly with impoverished interpersonal relations, even after controlling for subject’s intellectual abilities and illness severity.

27 In our study men with schizophrenia had more trouble with perception of affective prosody than women with schizophrenia, even than women would still have some difficulty when matched against comparison subjects. Sex-related deficits on affective prosody decoding might contribute to the well-documented sex differences in social functioning in schizophrenia. This gender differentiation could not be attributed to any significant differences in age, level of education, duration of illness, psychopathology, or schizophrenia type.

With regard to each emotion type separately, patients performed worse in anger, sadness, and surprise. Specifically male patients with schizophrenia presented worse recognition of anger, sadness, and surprise than healthy males, while female patients with schizophrenia showed worse performance only on processing sadness than healthy females. In general, the impairment in sadness and anger is in agreement with the negative valence hypotheses. Murphy and Cutting have suggested that the deficit in prosodic perception may be due to reduced performance on sadness.

14 Edwards et al. also tracked down problems in the prosodic perception of negative emotions, specifically in fear and sadness.

11 Studies in facial affect recognition also showed a specific deficit in recognition of negative emotions;

4 specifically in facial identification of fear and sadness.

11,28 Surprise is classified as neither a positive nor a negative emotion. Previous studies have failed to demonstrate a difference between the performance of patients and healthy participants on stimuli indicating surprise. Therefore, the lower score exhibited by our patients with schizophrenia in surprise prosody is difficult to explain.

Studies of brain damaged patients and brain functional imaging of healthy individuals exploring the neural structures by which human beings recognize emotion from prosody, have suggested that the recognition of emotional prosody draws on distributed and bihemispheric structures, with right inferior frontal regions (Brodmann’s area 10) being the most critical components of the system. These areas work together with more posterior regions in the right hemisphere (anterior parietal cortex), the left frontal regions, and subcortical structures (basal ganglia, amygdala), all interconnected by white matter.

29,30 Regarding the amygdala, it has been suggested that its role in recognizing emotion in prosody might not be crucial.

31,32 However, others have reported amygdala activation to emotional auditory stimuli.

33,34 Ross et al. compared patients with schizophrenia, right brain damage, and left brain damage and proposed that impairment in affective prosody in schizophrenia results from right hemispheric dysfunction.

12 Recently, a functional MRI study of a group of male patients with schizophrenia demonstrated a reversal of the normal right-lateralized temporal lobe response to affective prosody.

35Since there is a clear correlation between the level of difficulty of the APT for the healthy comparison subjects and the likelihood that the patients with schizophrenia would perform more poorly, we cannot determine whether there are true differential deficits in affect perception or whether these differences are due to psychometric artifact. Consequently, future research will need to address this issue.

In summary, patients with schizophrenia presented significant impairment in recognition of affective prosody compared with healthy subjects. This deficit was gender specific, as only men with schizophrenia presented significant impairment on recognition of affective prosody compared with healthy men. Finally, with regard to each emotion type separately, patients performed worse in emotions with negative valence, specifically anger and sadness. Future studies should also explore the consequences of these deficits on social and interpersonal functioning more directly.