What Is the Nature of the Neuropsychiatric Presentation of Addison’s Disease?

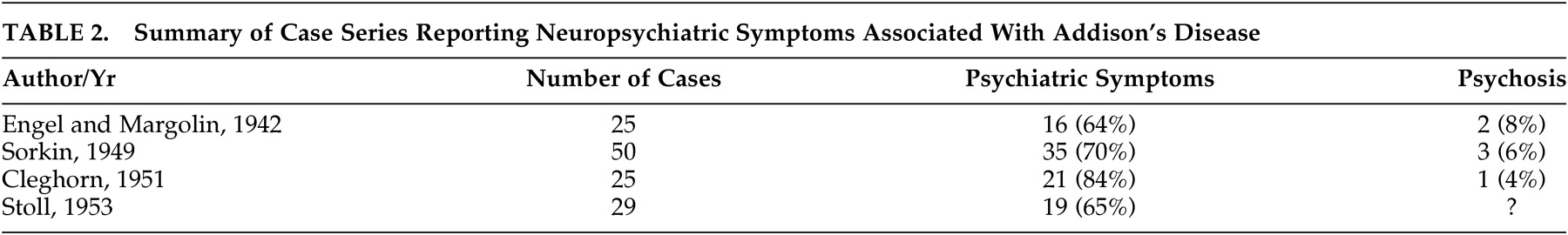

Four case series have documented mental status changes associated with cases of Addison’s disease (

Table 2 ). Engel and Margolin

3 in 1942 described 25 cases and documented a range of psychiatric symptoms in 64% of them. Mood and behavioral symptoms were most commonly reported, and psychosis was described in two patients. Sorkin,

4 in 1949, reported mental status changes in 70% of 50 Addison’s cases, and noted that mood and behavioral changes may be presenting features of the condition. He also reported three patients who developed psychosis. In 1951, Cleghorn

5 found apathy and negativism in 80% of 25 cases, with psychosis in one and seclusiveness, depression, and irritability occurring frequently. Stoll, in 1953, as reported by Smith et al.,

6 found psychiatric symptoms in 65% of 29 cases. Mood symptoms and decreased motivation were common in less severe cases, and an “acute organic brain syndrome” was associated with severe cases. These series indicate, therefore, that mild disturbances in mood, motivation and behavior are core clinical features of Addison’s disease. Psychosis and extensive cognitive changes, including delirium, appear to occur more rarely, but are associated with severe disease and may be the presenting feature of Addisonian crisis.

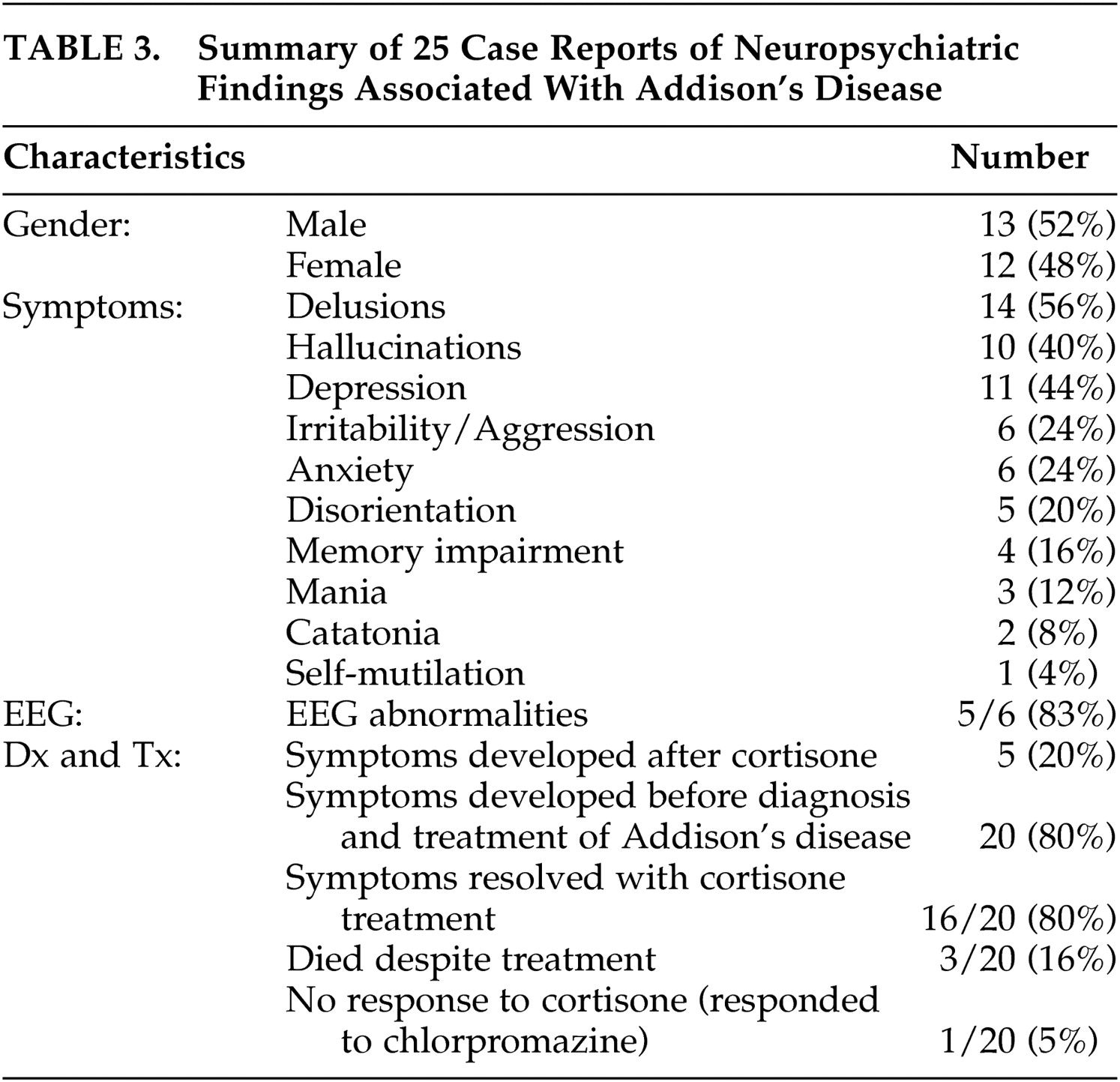

There have been 25 cases

7 –

27 of psychiatric symptoms associated with Addison’s disease reported in the English literature since 1940 (

Table 3 ). Largely these reports have described severe disturbances in functioning and psychosis. Rare presentations of Addison’s disease have included catatonia and self-mutilation. In 80% of the case reports, symptoms occurred before diagnosis and treatment, indicating that the mental status changes are a feature of Addison’s disease and not caused by treatment with cortisone. In the majority of cases, both physical and mental symptoms resolved with cortisone treatment in 1 week. However, mental symptoms occasionally persisted for months and reemerged with the precipitation of an Addisonian crisis.

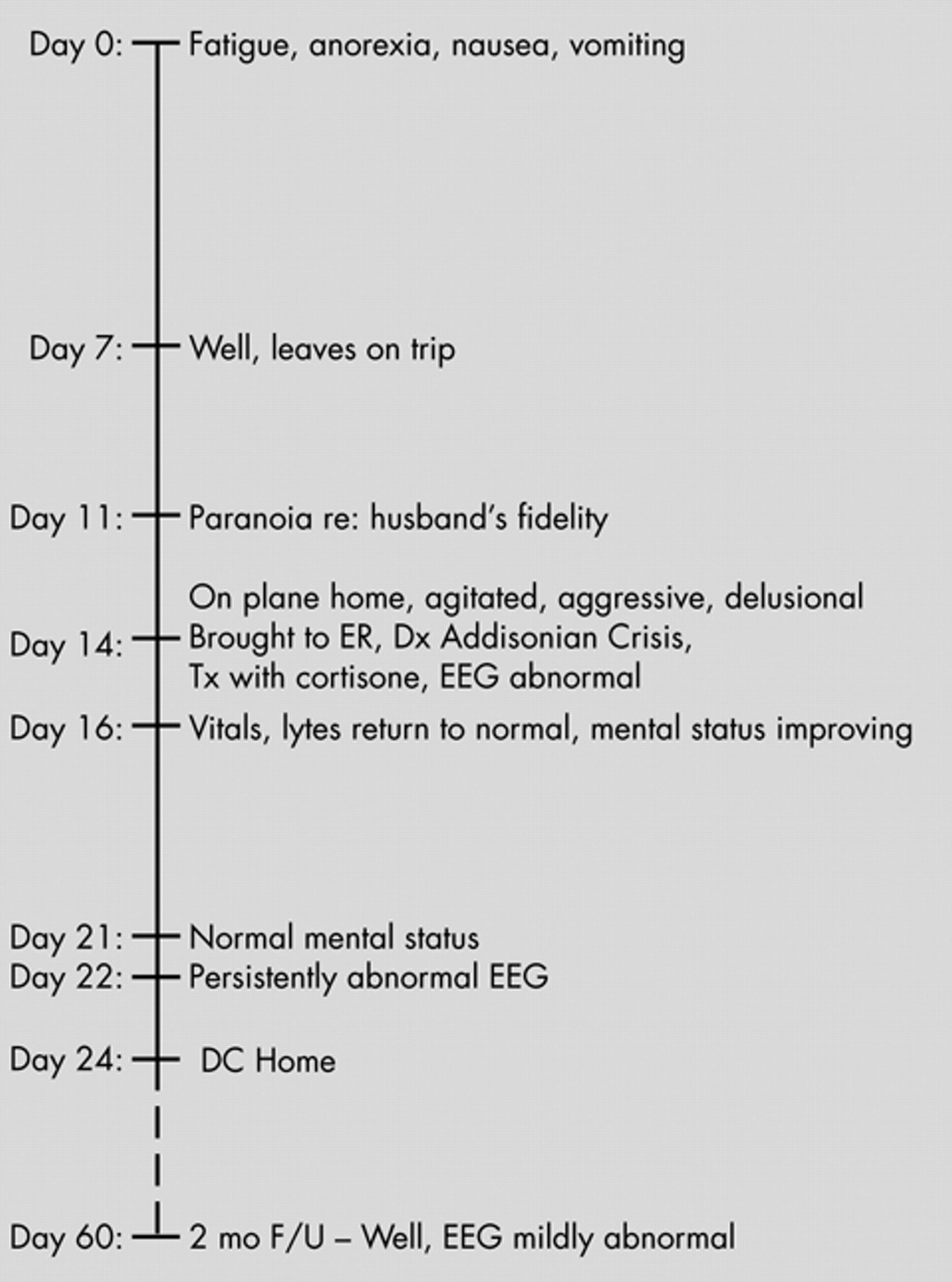

It is important to note that several terms have been used in the literature to describe the severe mental changes associated with Addison’s disease. These include psychosis, delirium, encephalopathy, and acute organic brain syndrome. Sometimes multiple terms are used to refer to a single patient. The patient we present can also be described by several diagnoses. She clearly had an encephalopathy, as evidenced by her abnormal EEG which showed generalized slowing. She could also be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition, namely Addison’s disease, given her prominent delusions and hallucinations that were likely a direct physiological effect of her hypoadrenocortical state. Finally she may have been delirious given her abrupt onset of agitation, disorientation, and perceptual disturbances along with an abnormal EEG. However, this is less likely as she did not have fluctuations in her level of consciousness, was able to focus and sustain attention and did not have any disturbances in speech or language. Regardless of the specific terminology used, it is clear that some patients with Addison’s disease have a disturbance in brain function and may develop a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms as a result.

What Are the Additional Clinical and Laboratory Features That Should Lead One to Consider a Diagnosis of Addison’s Disease?

When Thomas Addison first described the disease in 1855, tuberculosis adrenalitis was the most common cause. Currently, the most common etiology is autoimmune adrenalitis, but infection (including tuberculosis, fungal, HIV and syphilis), metastatic disease, drugs, and adrenoleukodystrophy may also give rise to Addison’s disease. The symptoms and signs observed in Addison’s disease depend on the rate and extent of destruction of the adrenal cortex.

28 The majority of patients with Addison’s disease have gradual destruction of the adrenal gland over months to years. However, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage or infarction or an acute stressor superimposed on chronic adrenal insufficiency can result in fulminant destruction of the adrenal gland and an Addisonian crisis.

28 This can occur in a matter of hours and is often life-threatening.

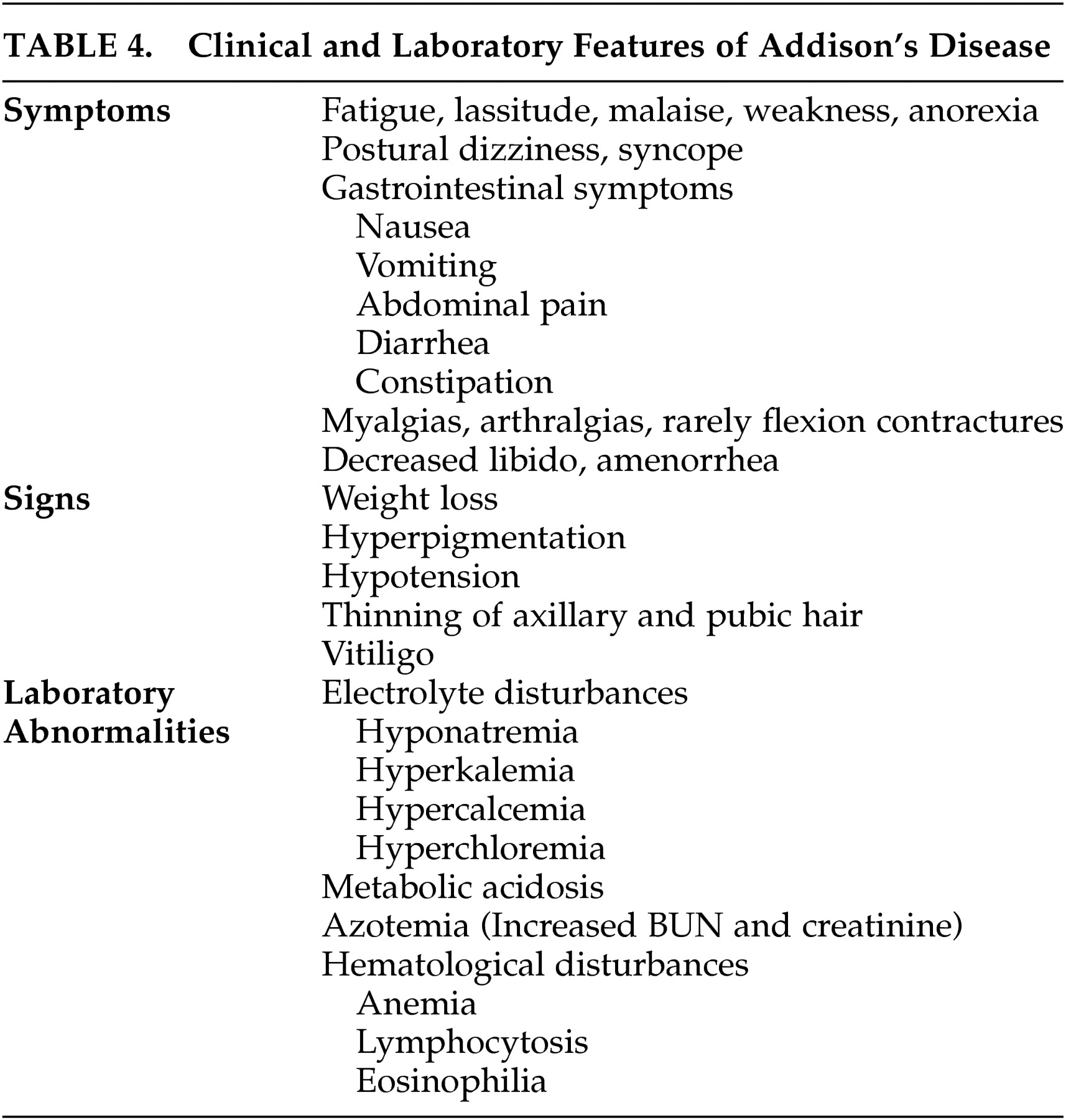

Patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency may have insidious onset of fatigue, lassitude, malaise, weakness, and weight loss. Hypotension can cause postural dizziness and syncope. Gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, and diarrhea are common. Myalgias and arthralgias are frequently observed and rarely flexion contractures of the legs can develop. Decreased libido, thinning of axillary and pubic hair, and amenorrhea may develop. Hyperpigmentation of the skin and mucosal surfaces is the most consistent symptom in Addison’s disease. It is caused by increased action of the melanocyte-stimulating hormone, which is co-secreted with ACTH in response to low circulating cortisol. Vitiligo can occur with autoimmune adrenal insufficiency as a result of destruction of dermal melanocytes.

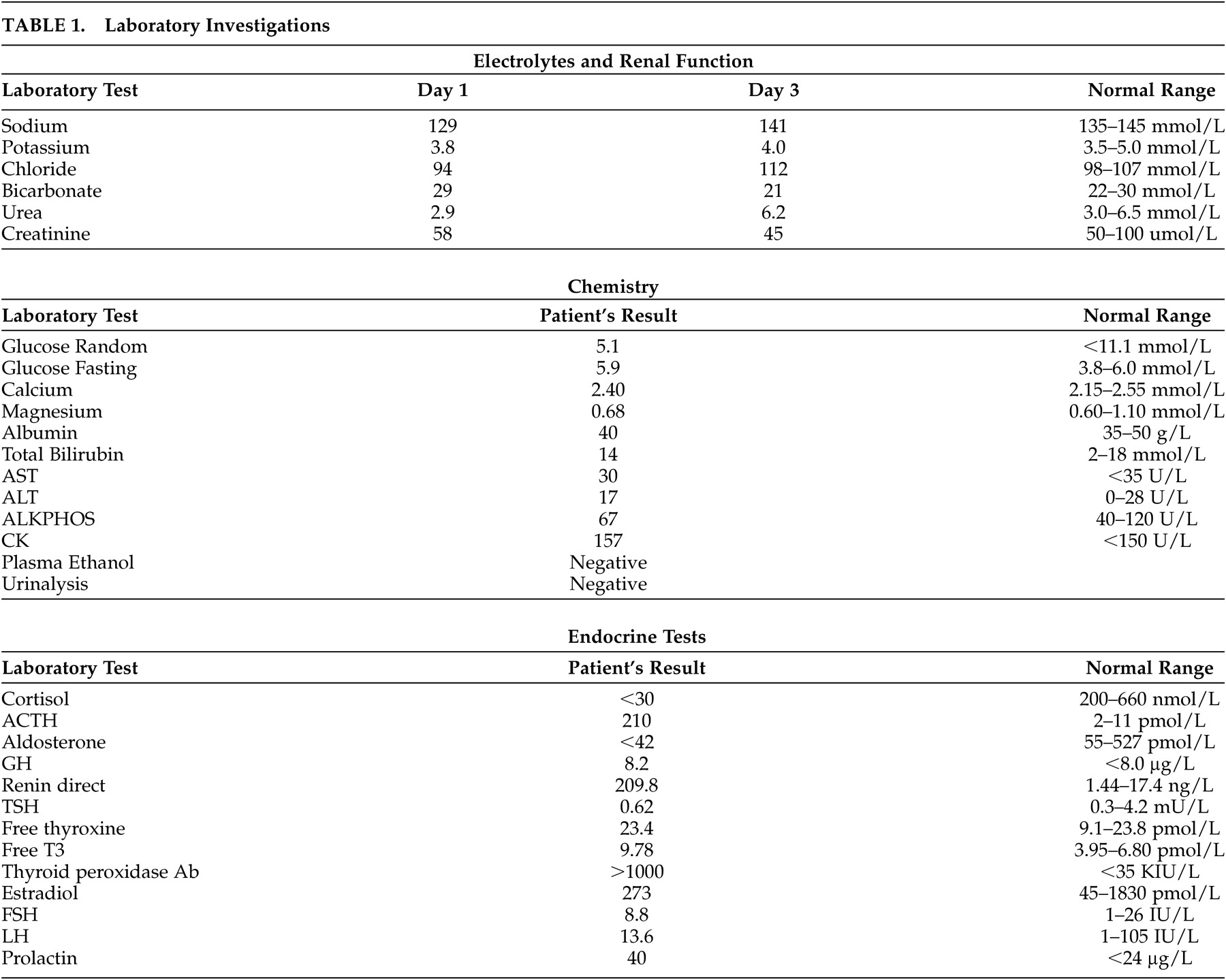

Electrolyte abnormalities are found in the majority of patients. Hyponatremia is caused by mineralocorticoid deficiency which results in volume contraction and corticosteroid deficiency, leading to an inappropriate secretion of ADH. Patients may report a craving for salt. Hyperkalemia and a mild hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis are caused by mineralocorticoid deficiency. Hypoglycemia can occur after prolonged fasting. Increased blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, a mild normocytic anemia, lymphocytosis, mild eosinophilia and hypercalcemia may be observed.

Patients with Addison’s disease may also present in Addisonian crisis with acute adrenal insufficiency in the setting of a serious infection or other acute stressors. Addisonian crisis is usually precipitated by mineralocorticoid depletion, and patients present with dehydration, hypotension, and shock. Patients may have nonspecific symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, weight loss, abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, confusion, and even coma. Fever may be caused by an infection, and exaggerated by glucocorticoid deficiency. Patients may have long-standing, undiagnosed Addison’s disease and also present with manifestations of chronic adrenal insufficiency, such as hyperpigmentation and electrolyte abnormalities. Addisonian crisis may also occur after bilateral adrenal hemorrhage or infarction. This should be considered in any patient presenting with severe hypotension or shock, abdominal, flank or back pain, fever, anorexia, nausea or vomiting, confusion, and abdominal rigidity or rebound tenderness in the absence of signs of chronic adrenal insufficiency, such as hyperpigmentation.

A diagnosis of Addison’s disease is based on the measurement of low plasma cortisol, elevated ACTH and the results of a corticotropin stimulation test. In a short corticotropin stimulation test, 250μg of cosyntropin (a synthetic form of ACTH) is given before 10 a.m., and plasma cortisol is measured before the test and 60 minutes after the injection. In patients with Addison’s disease, the adrenal cortex is unable to increase cortisol secretion in response to cosyntropin. When patients present with an Addisonian crisis, glucocorticoid treatment must not be delayed. Blood for serum cortisol, ACTH and serum chemistry should be drawn, and therapy with IV saline and dexamethasone should be initiated immediately. A short corticotropin stimulation test can then be performed as dexamethasone does not interfere with cortisol radioimmunoassay. Following testing, therapy with dexamethasone can be replaced with hydrocortisone. Low aldosterone and high renin are consistent with the diagnosis of Addison’s disease. If the cause of primary adrenal insufficiency is unknown, adrenal autoantibody tests and imaging of the adrenal glands can be performed.

What Is the Association Between Addison’s Disease and Other Endocrine Diseases?

Addison’s disease is most commonly caused by autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex, and may be accompanied by other autoimmune endocrine diseases. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I is an autosomal recessive condition most common in Finns, Sardinians and Iranian Jews that results in mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism and Addison’s disease.

29 Patients are also at risk of developing type 1 diabetes, hypothyroidism, pernicious anemia, alopecia, vitiligo, hepatitis, ovarian atrophy, and keratitis. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type II is a more common polygenic disorder resulting in a variety of autoimmune conditions.

29 Classically it refers to Addison’s disease plus thyroid autoimmunity (also called Schmidt’s syndrome) or type 1 diabetes, but the definition can be extended to include any two or more organ-specific autoimmune diseases.

Polyendocrine syndromes are believed to result from a failure of self-tolerance to a variety of molecules in different organ tissues.

29 As a result, autoantibodies against self-peptides may form. Greater than 90% of patients with Addison’s disease have autoantibodies to the enzyme 21-hydroxylase, a steroidogenic enzyme present in the adrenal cortex.

29 Specific genetic polymorphisms likely influence which specific autoimmune diseases develop.

In the case presented in this article, the patient was mildly hyperthyroid, with an elevated T3 level. This raises the possibility that thyroid dysregulation may contribute to the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Addison’s disease. In the literature, there are four cases that mention thyroid illness in patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms of Addison’s disease. In one case, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis was diagnosed at postmortem.

7 In a second case, there is mention that the patient was treated with “thyroid extract” although no indices are given to indicate that the patient was hypothyroid.

16 In a third case, the patient had a history of treated hypothyroidism and was treated with triiodothyronine in addition to hydrocortisone.

18 The fourth patient had been previously diagnosed with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

26 Importantly, there were no active abnormalities in circulating thyroid hormones reported in any of these cases. Therefore, it is unlikely that abnormal levels of thyroid hormones play a significant role in the neuropsychiatric presentation of Addison’s disease.