T he corticobasal syndrome refers to a constellation of signs and symptoms, including progressive asymmetric rigidity and apraxia, alien limb phenomenon, cortical sensory loss, myoclonus, and dystonia, which were initially considered to be characteristic of corticobasal degeneration.

1 –

4 The accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of underlying corticobasal degeneration among patients with corticobasal syndrome is only about 50%.

5 –

8 Further, the clinical spectrum of pathological corticobasal degeneration includes not only corticobasal syndrome, but primary progressive aphasia, frontotemporal dementia, and progressive supranuclear palsy.

4,

8,

9 The clinicopathological discrepancies bring into question the validity of studies describing psychiatric features of corticobasal degeneration based on clinical diagnosis alone.

There are very few reports on the neuropsychiatric features of corticobasal degeneration. Only one involved pathologically proven cases,

10 while others were based on clinical diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration.

11,

12 Our study is based upon 36 consecutive pathologically confirmed cases. Neuropsychiatric characterization of these corticobasal degeneration cases could contribute to a more comprehensive clinical description of this pathological entity.

METHOD

We reviewed the clinical records of 36 consecutive pathologically diagnosed cases of corticobasal degeneration evaluated between 1990 and 2005, in the departments of neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. As part of the ADRC protocol, patients were invited to participate in the advanced directive for autopsy study by signing an Institutional Review Board-approved consent form.

Nomenclature

We utilized the neuropsychiatric nomenclature in corticobasal degeneration described by Cummings and Litvan.

12 Disinhibition, impulsivity and aggressive behavior are collectively referred to as frontal-lobe type behavioral alterations. Similarly, purposeless, repetitive, and compulsive behaviors are referred to as obsessive compulsive behavior that may not necessarily be identical with obsessive compulsive disorder as defined by the DSM-IV.

13Case Definition

Each case met the published research criteria for neuropathological diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration;

14 the minimum required findings were: cortical and striatal tau-positive neuronal and glial lesions, especially astrocytic plaques and thread-like lesions in both white and gray matter along with neuronal loss in focal cortical regions and in the substantia nigra. The neuropathological diagnoses were rendered by the two neuropathologists (DWD in the Jacksonville Mayo Clinic and JEP in the Rochester Mayo Clinic), one of whom (DWD) led an NIH-supported task force that defined these criteria. Once a case met the neuropathological criteria for corticobasal degeneration, the medical record was reviewed by a neuropsychiatrist (YEG) for clinically relevant data. Neuropsychiatric features were considered present if they were specifically described in the records. A deliberate effort was made to look for visual hallucination as it had been reported as a prominent symptom in other parkinsonian syndromes, particularly in dementia with Lewy bodies.

15,

16 The findings were then analyzed as they related to recognizable neuropsychiatric syndromes.

RESULTS

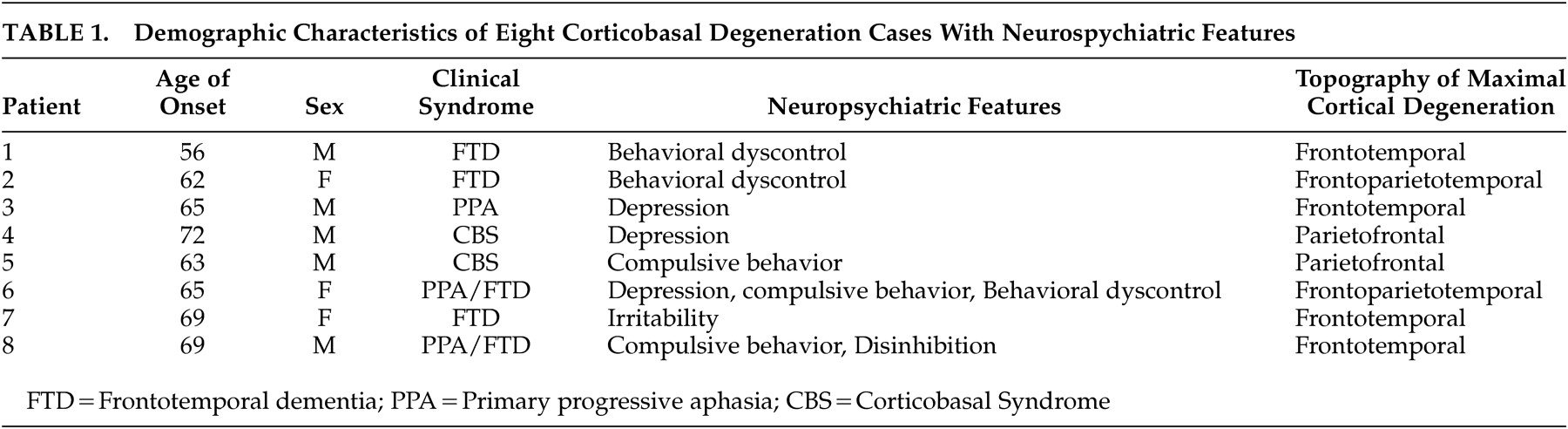

There were 16 women and 20 men with pathologically confirmed corticobasal degeneration. Eight out of the 36 patients (22%) had well-documented neuropsychiatric problems. The mean age of onset of symptoms for the whole sample (N=36) was 64.4 (SD=6.2) years, and the mean age of onset of symptoms for the eight patients with neuropsychiatric features was 63.8 (SD=6.2) years. The demographic characteristics of these eight patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms are shown in

Table 1 .

The clinical manifestations of the eight patients can be divided into three syndromes based on the diagnoses rendered by the examining neurologists. These were progressive aphasia/frontotemporal dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and corticobasal syndrome. The first group consisted of three patients (Patients 3, 6, 8; see

Table 1 ) that were initially clinically diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia. In subsequent longitudinal follow-up, the primary progressive aphasia evolved into an overlapping frontotemporal dementia syndrome. The case record of one patient (Patient 8) is typical of the neuropsychiatric features of this group. This patient initially presented with progressive language difficulty and his baseline neurological examination was normal except for decreased right arm swing and very mild expressive aphasia. Investigations revealed normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain but the positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed hypometabolism in left peri-Sylvian area. The baseline clinical data indicated no past psychiatric history. Later, the patient developed compulsive behaviors, such as excessive hand washing, teeth brushing, and picking up every wild flower or stick that he came across when going for a walk. Hence, psychiatric consultation was sought and a diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive behavior in the setting of a neurodegenerative disorder was entertained. Over a period of 2 to 3 years, he was also noted to have developed socially inappropriate and disinhibited behaviors along with a voracious appetite and excessive eating. The clinical diagnosis was subsequently changed from primary progressive aphasia to frontotemporal dementia.

The second group (Patients 1, 2, 7) consisted of patients who were clinically diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia. Their neuropsychiatric manifestations included aggressive behavior, impaired judgment, new onset excessive alcohol consumption, and irritability. The case record of Patient 1 is typical of this group. The patient initially presented with irritability, indecision, somnolence, and decreased spontaneous speech; in subsequent follow-ups, he developed glabelar and snout reflexes, worsening aphasia, and personality change. He increasingly exhibited impulsiveness, poor judgment, and aggressive behavior. For instance, the patient tried to strangle his wife while she was visiting him in the hospital. This and other similar behaviors led to his transfer to a long-term psychiatric facility.

The third group consisted of two patients (Patients 4 and 5) who were clinically diagnosed with corticobasal syndrome, which was also consistent with the neuropathological diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. The neurological findings of patients with corticobasal syndrome were summarized by one of us (BFB, a board-certified neurologist and a specialist in behavioral neurology). The patients exhibited slowly progressive asymmetric rigidity and apraxia, consistent with the widely reported literature on corticobasal degeneration. In association with these neurological findings, depression developed in one patient that was refractory to antidepressant medication and ECT. The other patient exhibited new onset compulsive cleaning. None of the 36 patients experienced visual hallucination.

DISCUSSION

We report neuropsychiatric features in 36 consecutive pathologically diagnosed corticobasal degeneration cases. The major neuropsychiatric findings noted were frontal lobe-type behavioral alterations, such as disinhibiton and impulsiveness, obsessive compulsive behavior, and depression. The absence of visual hallucination in any of our cases is in sharp contrast to other parkinsonian syndromes, particularly dementia with Lewy bodies in which the frequency of visual hallucination is 60% or higher;

15 –

17 similarly, the frequency of visual hallucination in Parkinson’s disease is 6% or higher.

12 If future prospective studies confirm this particular finding, then it could have an impact on clinical practice i.e., a physician should be less inclined to make the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration in a patient with parkinsonism and visual hallucination. On the other hand, depression is a common problem in many neurodegenerative disorders, including corticobasal degeneration (70%), Parkinson’s disease (up to 90%) and Alzheimer’s disease (38%).

12By comparing scores on Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) between subjects with clinically diagnosed corticobasal degeneration (N=15), progressive supranuclear palsy (N=34), and healthy subjects (N=25), Litvan et al.

11 observed that depression and irritability were more frequent, whereas apathy was less frequent, in corticobasal degeneration compared with progressive supranuclear palsy. In a more recent analysis from these same investigators, three behavioral syndromes were noted in seven of the 20 clinically diagnosed corticobasal degeneration subjects: frontal lobe-type behavioral alterations, depression and obsessive compulsive behavior.

12 The findings in our series were consistent with these three behavioral syndromes with the added caveat that our cases were pathologically proven corticobasal degeneration.

To date, the largest number of pathologically confirmed cases of corticobasal degeneration in whom neuropsychiatric features was sought was only 14. These cases were from seven major medical centers in Austria, the United Kingdom and United States;

10 50% of these cases had psychiatric manifestations. The presence of apathy, irritability, and disinhibition predicted poor survival.

10 The percentage of cases with neuropsychiatric features in our series (22%) was smaller. Since this was a retrospective chart review study, we might have underestimated the frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy. Clinicians did not routinely use a structured interview, such as the NPI; hence, it was very likely that apathy might have been misclassified as depression. Future prospective neuropsychiatric studies, performed in a detailed and standardized manner, will more accurately describe the prevalence and features of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of corticobasal degeneration. However, we are reporting the largest autopsy-verified series, confirmatory of the literature

12 so far, which will serve as a guide for a prospective study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants K01 MH68351 (NIMH) and P50 AG16574 (NIA), and the State of Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Initiative.