A pathy is characterized by loss of initiation and motivation, decreased social engagement, and emotional indifference.

1 It manifests as poor persistence, lack of interest, blunted emotional response, and lack of insight. Apathy has profound consequences on both patients and caregivers and affects activities of daily living. In a study of patients with Alzheimer’s dementia, the presence of apathy was associated with impairment in one of a common set of activities of daily living (dressing, bathing, using the toilet, walking, and eating).

2 Apathy transcends diagnosis, occurring in mental illnesses and neurodegenerative disorders. For example, 53% of patients with major depression have been reported to be apathetic,

3 and 70% to 90% of patients with Alzheimer’s dementia and 33.8% of patients with vascular dementia suffer from apathy at various stages of illness.

3,

4 Thus, apathy is common and may have important consequences for function.

Assessment of apathy has improved recently with the development of specific rating scales. The Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES)

5 was developed to assess apathy and discriminate it from depression. We used this 18-item scale, with scores ranging from 18 to 72, to assess apathy in behavioral, cognitive, and emotional domains over the course of the previous 4 weeks. Three questions have negative syntax to ensure validity of responses. It has good internal consistency (coefficient α>0.86) and test-retest reliability (r>0.76). Clinician-rated and self-rated versions have been shown to discriminate apathy from depression.

The treatment of apathy continues to be poorly understood, with very little empirical data available for guidance. Several agents have been used with mixed results in treating apathy, including amantadine,

6 amphetamine, bromocriptine,

7 bupropion,

8 and methylphenidate.

9,

10 Recent research has suggested a role for noradrenergic and dopaminergic systems in the neurobiology of apathy.

11 Although the use of methylphenidate, a potent noradrenergic and dopaminergic releaser, has been well documented for the treatment of fatigue and depression, its use for the treatment of apathy is only reported in a few case reports. All of these case reports on methylphenidate treatment of apathy are in patients with neurodegenerative disorders rather than with primary mental illnesses. None of these reports specifically assessed apathy using the AES.

METHOD

Patients who reported apathy as a symptom of their primary psychiatric diagnoses were identified from the Mental Health Clinic. Comorbid diagnoses included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), vascular dementia with depression, and major depressive disorder, recurrent type. The comorbid conditions were fairly stable and were being treated with psychotropics. Apathy was assessed using the AES prompted by self-report by patient. Approval from the Omaha VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board was obtained for this case series. Methylphenidate was used as an adjunctive agent for the treatment of apathy, which was reassessed at 4 weeks.

CASE REPORTS

Case A

A 57-year-old man with major depressive disorder and PTSD was clinically stable on a regimen of 200mg of sertraline and 100mg of trazodone. He presented with a lack of drive and desire to do anything, along with a poor sleep pattern. A regimen of methylphenidate was started at 10mg b.i.d. and titrated to 20mg b.i.d. in 4 weeks. He reported an improved sleep pattern resulting in feeling more awake during the day, a decreased craving for food, and looking forward to fishing trips. He reported a dry cough immediately after starting methylphenidate, which subsided spontaneously with continuing treatment. His AES score decreased from 60 to 37 over the course of 4 weeks. He contacted a few of his friends by phone during this period and was noted to describe more interests and daily activities.

Case B

A 47-year-old woman who had major depressive disorder presented with a lack of drive and a lack of initiative. Her depression was being treated with a regimen of fluoxetine, 60mg/day, and was noted to be clinically stable. Behavioral interventions of keeping a log of her activities, attempting to gradually increase activities and adjusting her sleep routine were not helpful. She scored 57 on the AES and was started on a regimen of methylphenidate at 10mg b.i.d., which was titrated to 20mg b.i.d. in a week. After 4 weeks, she reported significant improvement in her apathy and scored 31 on the AES. Her subjective account included many details about her activities and a desire to take up her past job. She was able to wake up early and felt less groggy in the morning. She also noticed that her quality of sleep improved.

Case C

A 70-year-old man had vascular dementia and depression. His cognitive problems were stable throughout the treatment and he had not had any recent vascular incidents. He was being treated with a regimen of donepezil, 10mg/day, and bupropion, 75mg b.i.d. At initial intake, he was disheveled, lacked interest, and showed a negligence of personal hygiene. He was noted to have no initiative and spent most of the day sitting on the couch watching TV. He scored 60 on the AES and was started on a regimen of 5mg b.i.d. of methylphenidate, which was titrated to 10mg b.i.d. in a week. At follow-up, he scored 49 on the AES. He denied any improvement, although his wife was quick to add that he had bought new puppies and spent a lot of time caring for them. She added that dogs had previously been of great interest to the patient and that she had worried when he had stopped showing interest in them. His personal hygiene improved during treatment.

Case D

A 77-year-old man with a history of recurrent major depressive disorder presented with a lack of motivation and lack of desire to do anything. His current episode of depression had been triggered by selling his farm and the role-transition stemming from this. He was frustrated that he could not farm anymore and could not drive his tractor. His mood symptoms improved with a regimen of citalopram, 40mg/day, and were reported to be stable subjectively by him. The patient scored 51 on the AES and was started on a regimen of 5mg b.i.d. of methylphenidate, which was titrated to 10mg b.i.d. in 2 weeks and later to 20mg b.i.d. He reported significant improvement in his motivation. He bought a new car, resumed calling his friends, and attended church regularly. He began to use his tractor after a long absence. He scored 39 on the AES at 4 weeks.

DISCUSSION

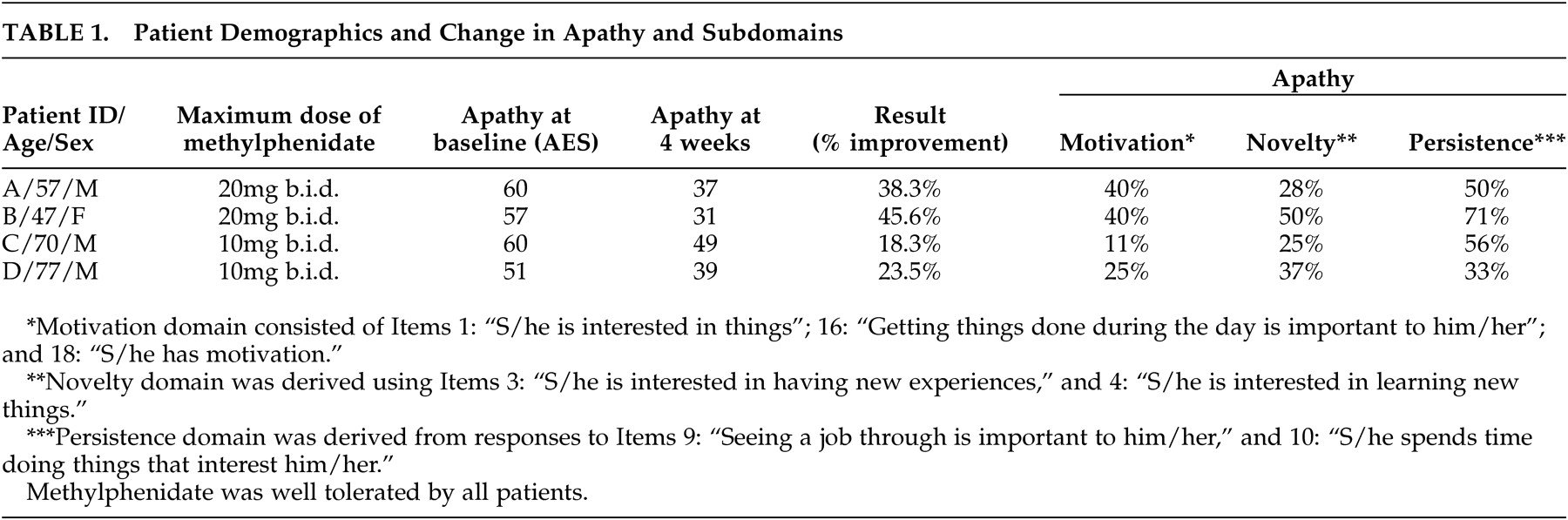

Significant improvement in apathy and its subdomains was noted in all four patients (

Table 1 ). Subdomains of apathy were obtained by pooling items from the AES addressing motivation (Items 1, 16, and 18), novelty (Items 3 and 4), and persistence (Items 9 and 10). In this case series, four patients being treated for a variety of mental illnesses were evaluated with the AES.

6 The patients were then all treated with methylphenidate; none of the other medications was changed. No other intervention was provided during the course of this observation other than nonsystematized supportive therapy offered as part of the routine clinical visit. None of the patients reported major life changes or stressors that could confound findings. None of the patients complained of serious side effects. Vital signs, including blood pressure and pulse, were monitored at each visit. No major changes were noted. One of them complained of dry cough starting immediately after starting the medication, but this subsided spontaneously. All were evaluated at 4 weeks and had continued to take methylphenidate.

A significant improvement in apathy was noted with methylphenidate. This finding is supported by other case reports of treatment of apathy in degenerative disorders.

9,

10 None of the concomitant medications was discontinued, demonstrating the relative lack of drug interactions with methylphenidate. Of note, three of the four patients were being treated with serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which have been linked with apathy.

12Limitations of this study include a lack of an objective assessment of depression because of which it cannot be ascertained whether the effect of methylphenidate on apathy was independent of its effect on depression. Nevertheless, the robust improvement in apathy and its subdomains by methylphenidate raises the possibility of using this agent as an additional treatment in this population. Duration of observation was only 4 weeks, which does not allow for adequate assessment of possible chronic side effects of methylphenidate. Longer studies are also needed to test whether apathy will improve further. More research needs to be done in this area, including randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of methylphenidate and other noradrenergic and dopaminergic agents for the treatment of apathy.