P rogress in understanding the pathogenesis of HIV-1-associated dementia continues to be made, but details on how the neuropathogenic pathways interact with each other are not completely understood.

1 –

6 By identifying key elements involved in HIV-1-associated dementia (HAD) pathogenesis, we may be able to target interventions to treat or prevent it. Recently, we performed a cross-sectional study and found an association between circulating HIV-1 proviral DNA (HIV DNA) levels and HAD, independent of plasma HIV-1 RNA levels.

7 This remains the only prior investigation of the association between HIV DNA and HAD. In the study, we tested the null hypothesis of no association between HAD and HIV DNA in specimens from individuals at opposite ends of the cognitive diagnostic spectrum: HAD and normal cognition. We used the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) diagnostic criteria for HAD, which were established in the pre-HAART era, and found a significant association of HIV DNA with HAD (OR=2.83; 1.57–5.08, p<0.001).

7,

8 We hypothesized that HIV DNA levels may affect different areas of the brain uniquely, thus leading to specific neuropsychological deficits. If HIV DNA is shown to associate differentially with specific neuropsychological deficits, this may suggest that specific areas of the brain are affected differently. Therefore, focusing on neuropsychological deficits to clinically characterize patients may provide an advantage over using a diagnosis of HAD.

7 In the current HAART era, markers for HAD, a diagnosis which relies on global neuropsychological deficits, remain to be identified.

1,

9,

10 Though additional studies are necessary to establish HIV DNA as a marker for HAD, the use of HIV DNA as a prognostic marker for neuropsychological deficits could potentially be a clinical and research tool. A recent report

11 by other investigators found that HIV DNA levels predicted HIV-1 disease progression to AIDS. Rouzioux et al.

11 suggested that HIV DNA levels could be a useful clinical marker to help define the best time to initiate treatment. The study supported the possibility that HIV DNA may be involved in disease pathogenesis and prompted us to look at its association with neuropsychological deficits.

In this exploratory study, we analyzed an expanded data set to explore the association of HIV DNA with specific neuropsychological deficits. The objectives were to assess the relationship of baseline HIV DNA to baseline and yearly neuropsychological deficits for 2 years, and to determine whether baseline HIV DNA predicts subsequent neuropsychological deficits. Based on our earlier observation suggesting that HIV DNA may be predominant in circulating monocytes/macrophages, we hypothesized that HIV DNA levels and neuropsychological deficits would be transient and both would co-vary over time.

7RESULTS

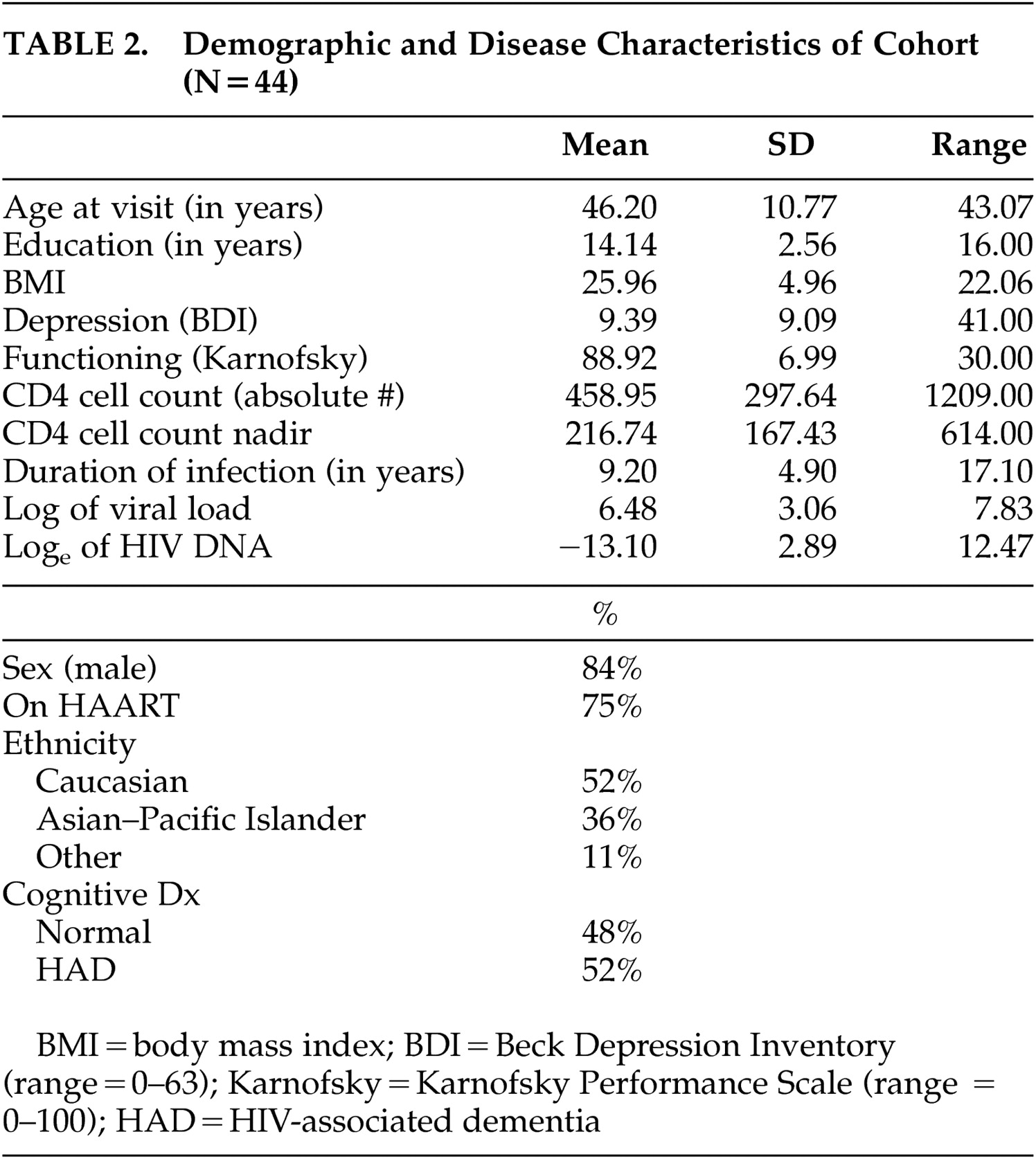

Characteristics and demographics of the subjects are summarized in

Table 2 . The mean age at entry was 46.2 (SD=10.77) years with the mean number of years of education being 14.14 (SD=2.56). The mean BDI score was 9.39 (SD=9.09) and the mean Karnofsky score was 88.92 (SD=6.99). The mean duration of HIV-1 infection as self-reported was 9.2 (SD=4.9) years with nadir CD4 cell count reported as 217 cells/μL (SD=167.43).

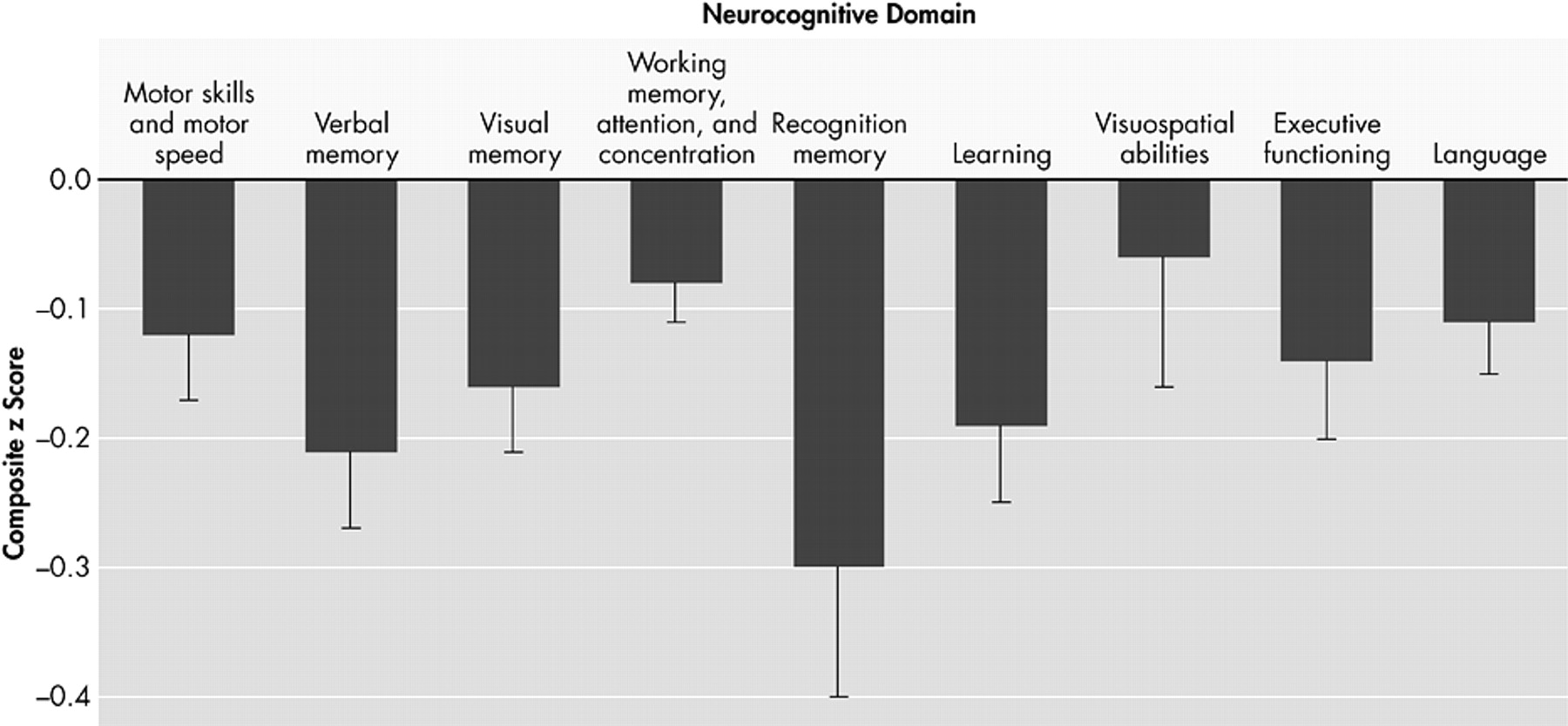

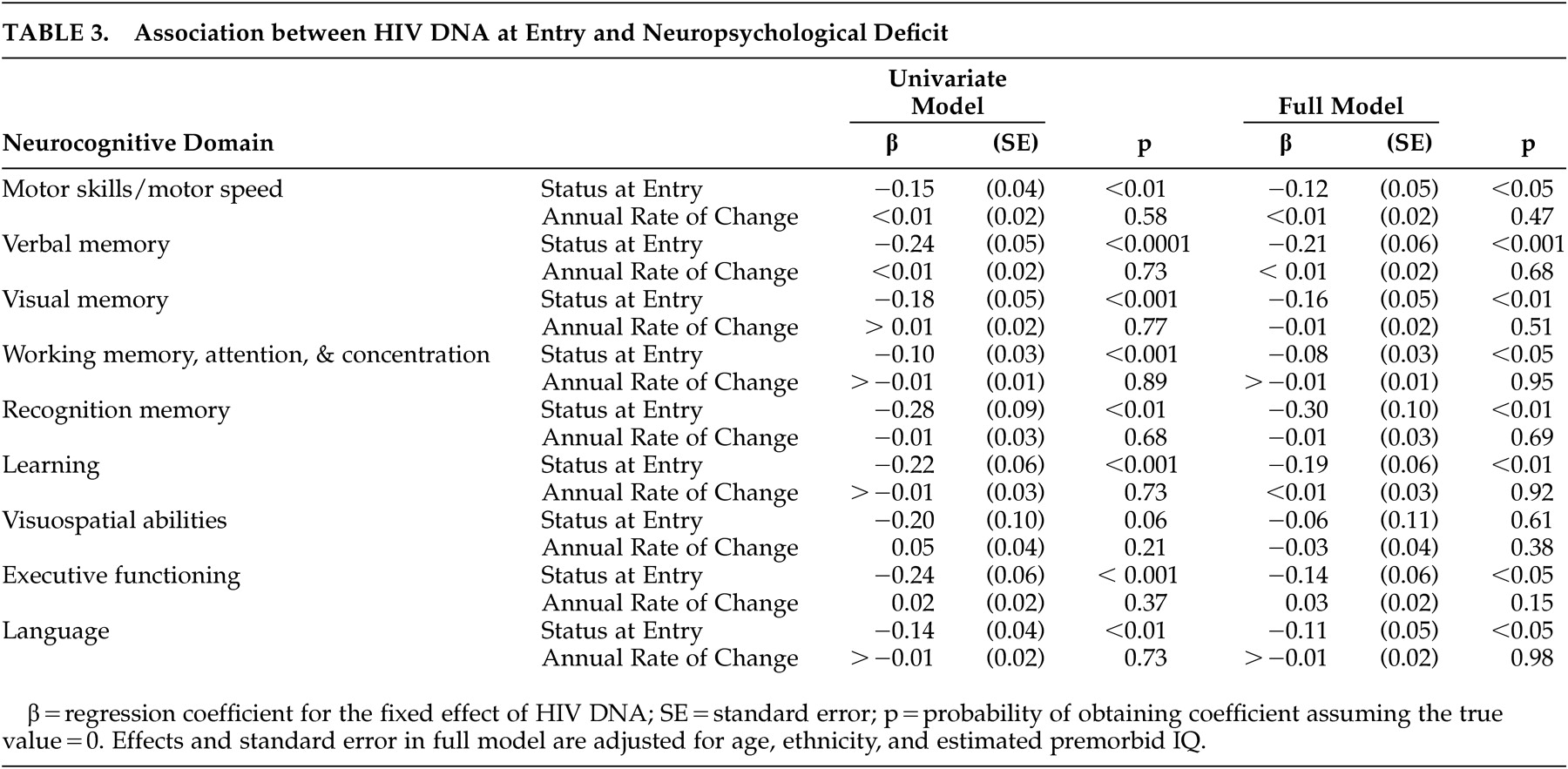

The decrement in baseline of each neuropsychological deficit associated with HIV DNA is plotted in

Figure 1, and adjusted for age, ethnicity, and estimated premorbid IQ, where ethnicity and IQ are not confounded with cognitive diagnosis. For each unit increase in log

e of HIV DNA, there is a decrease in neuropsychological deficit. Neuropsychological deficits were significantly associated with baseline HIV DNA in all deficits except for one: visuospatial abilities (regression coefficients range from −0.27 to −0.10, p<0.01) (

Table 3 ). The effect of HIV DNA on neuropsychological deficits remained significant after adjusting for age, ethnicity, and estimated premorbid IQ. When analyses were repeated using only individuals with undetectable plasma HIV-1 RNA levels, the association between neuropsychological deficits and baseline HIV DNA remained significant (N=26, p<0.01). The effect for time in the unconditional growth model was significant in only two of the nine domains: visual memory (regression coefficient=0.18, SE=0.04, p<0.0001) and executive functioning (regression coefficient=0.22, SE=0.04, p<0.0001). However, the variance component for residual variance in change over time was significant for only one domain: motor skills and motor speed (z=2.48. p<0.01). In this exploratory analysis, baseline HIV DNA baseline was not associated with neuropsychological deficit change over the subsequent 2 years.

DISCUSSION

Much progress has been made in understanding the pathogenesis of HAD, but the mechanisms leading to disease progression are still not completely delineated.

21 –

24 We previously reported that high HIV DNA levels were associated with HAD and hypothesized that HIV DNA, independent of plasma HIV-1 RNA levels, was involved in HAD pathogenesis.

7 In our current exploratory study, we expanded our prior results with a more complete dataset using less restrictive endpoints. We demonstrated that HIV DNA was significantly associated with baseline neuropsychological deficits in all but one domain (visuospatial abilities), but did not predict subsequent changes in neuropsychological deficits. Although not shown yet, we hypothesize that HIV DNA levels and neuropsychological deficits are transient and both factors may co-vary over time; however, the limitations of this exploratory study cannot conclusively rule out any potential role for HIV DNA as a predictive marker. The lack of predictive value is best understood against the backdrop of minimal temporal variation that was available for the analysis. Only two deficits (visual memory and executive functioning) showed a significant effect for time in the unconditional growth models, indicating that the average trajectory over 2 years was fairly flat. The time effect alone can be assessed on the outcome without any additional predictors.

In this model, the coefficients indicate the amount of change in the outcome that is attributable to a unit of change in the predictor. The direction of change is indicated by the sign of the beta. In this case, the positive sign of the betas indicate improved performance in the two outcomes, which could possibly be due to a practice effect. The fact that only these two outcomes were significant suggests that there may be too little temporal variability in the data for the question of HIV DNA’s impact on subsequent change to be adequately posed.

The one deficit (motor skills and motor speed) that showed a significant residual variance component for change over time in unconditional growth models suggests that little variation was available to be explained by HIV DNA or other predictors added to the model. The residual variance is the variance that is not explained by the fixed and random effects in the mixed model. The mixed model allowed for testing of the residual variance of the trajectory of motor skills and motor speed to determine whether it was statistically different. Thus, the findings suggest the possibility that the lack of association may be partly a function of the small amount of change that was available to be explained to begin with, and that if the amount of change were increased, for instance, by prolonging the period of observation, the predictor would have a better chance of being associated with change over time.

The study is limited by including only subjects with normal cognition and HAD, excluding individuals with mild or intermediate neuropsychological deficits, thus limiting the generalizability of the results.

7 An additional limitation of interpreting the results of the study is the absence of comparable and adequate neuropsychological norms for the entire subject group, particularly the norms used for the older subjects in which data for comparable education levels were lacking. Thus, the results of this study should be taken in the context that various norms for the subject groups may place limitations on the comparable standard scores and diagnoses.

HIV DNA has been studied by other investigators

11 to assess HIV-1 disease progression and has been found to predict progression to AIDS. Rouzioux et al.

11 reported on a cohort of individuals who were not on antiretroviral treatment initially but subsequently were put on therapy; and demonstrated that HIV DNA was a marker for progression to AIDS, independent of plasma HIV-1 RNA levels.

11 In our previous study, to assess the association of HIV DNA with HAD, we used the AAN diagnostic criteria for HAD, which are based on combined functional impairments and neuropsychological deficits.

1,

8,

12,

25 The HIV-1-associated cognitive deficits now observed in developed countries may be less severe and their trajectories more varied than the dementia label implies. Nevertheless, even in an era where viremia in developed countries is declining among HIV-1-infected individuals, HAD and milder neurocognitive diagnoses clearly carry clinically relevant functional implications.

In the current study, we looked specifically at neuropsychological deficits for associations with HIV DNA in an attempt to identify focal deficits that might be affected by HIV DNA. Because we believe that HIV DNA could potentially co-vary and affect neuropsychological deficits over time, future studies should focus on: increasing the amount of explainable temporal variation by analyzing neuropsychological deficits over a longer duration in order to assess the predictive value of HIV DNA on neuropsychological deficits; sampling older individuals whose rate of change over a given period is likely to be greater; and including subjects with intermediate neuropsychological deficits.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that the neuropsychological deficits associated with HIV DNA levels may be global in nature. Any forthcoming studies to assess the association between HIV DNA and subsequent neuropsychological deficits should require periods of observation in excess of 2 years to address the predictive value of HIV DNA. It is possible that the lack of association of baseline HIV DNA levels with subsequent neuropsychological deficits may suggest that HIV DNA and neuropsychological deficits co-vary over time. Similar to the scenario where plasma HIV-1 RNA levels fluctuate with nonadherence of HAART, HIV DNA copies in monocytes/macrophages may also change through some as-of-yet unidentified influence. Thus, if HIV DNA influences neuropsychological deficits, resulting in the two entities co-varying over time, this fact may need to be taken into consideration in developing future treatment or preventative strategies.